Concerto transcriptions for organ and harpsichord (Bach)

The concerto transcriptions of Johann Sebastian Bach date from his second period at the court in Weimar (1708–1717). Bach transcribed for organ and harpsichord a number of Italian and Italianate concertos, mainly by Antonio Vivaldi, but with others by Alessandro Marcello, Benedetto Marcello, Georg Philipp Telemann and the musically talented Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar. It is thought that most of the transcriptions were probably made in 1713–1714. Their publication by C.F. Peters in the 1850s and by Breitkopf & Härtel in the 1890s played a decisive role in the Vivaldi revival of the twentieth century.

History, purpose, transmission and significance

| “ | The pleasure His Grace took in his playing fired him with the desire to try every possible artistry in his treatment of the organ. | ” |

| — Nekrolog, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Johann Friedrich Agricola[2] | ||

Bach's concerto transcriptions reflect not only his general interest in and assimilation of musical forms originating in Italy, in particular the concertos of his Venetian contemporary Antonio Vivaldi, but also the particular circumstances of his second period of employment 1708–1717 at the court in Weimar.

During his first brief period in Weimar in 1703 Bach was employed as a court violinist for seven months by Johann Ernst III, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, who ruled jointly with his elder brother Wilhelm Ernst, Duke of Saxe-Weimar. Wilhelm Ernst's Lutheran piety contrasted with his younger brother's alcoholism. On Johann Ernst's death in 1707, he was succeeded as coregent by his elder son Ernst August, who lived with his younger stepbrother, Prince Johann Ernst, outside the ducal Wilhelmsburg in the Rotes Schloss. A talented amateur musician, from an early age Prince Johann Ernst had been taught the violin by the court violinist Gregor Christoph Eilenstein. Johann Ernst studied the keyboard with Bach's distant cousin Johann Gottfried Walther, after he became organist at the Stadtkirche in Weimar in 1707. The following year, when Bach himself was appointed as organist in Weimar in the ducal chapel or Himmelsburg, he not only had at his disposal the recently renovated chapel organ but also the organ in the Stadtkirche. In the Wilhelmsburg, Wilhelm Ernst had already revived the court orchestra, of which Bach eventually became Concertmaster in 1714. As well as music-making in the Wilhelmsburg, Bach was almost certainly involved in the parallel more secular musical events in the Rotes Schloss organised by August Ernst and Johann Ernst. Harpsichords were available to Bach at both venues.[4]

Jones (2007) traces the influences on Bach's early keyboard compositions—in particular his sonatas (BWV 963/1, BWV 967) and toccatas (BWV 912a/2, BWV 915/2)—not only to the works of his older compatriots Kuhnau, Böhm and Buxtehude, but also to the works of Italian composers from the end of the seventeenth century; in particular the chamber sonatas of Corelli and the concertos of Torelli and Albinoni.[5]

Early works like BWV 912a and BWV 967, probably composed before 1707, also display concerto-like elements. The first documented evidence of Bach's engagement with the concerto genre can be dated to around 1709, during his second period in Weimar, when he made a hand copy of the continuo part of Albinoni's Sinfonie e concerti a 5, Op. 2 (1700). Earlier compositions had been brought back to Weimar from Italy by the deputy Capellmeister, Johann Wilhelm Drese, during his stay there in 1702–1703. In 1709 the virtuoso violinist Johann Georg Pisendel visited Weimar: he had studied with Torelli and is likely to have acquainted Bach with more of the Italian concerto repertoire. In the same year Bach also copied out all the parts of the double violin concerto in G major, TWV 52:G2, of Georg Philipp Telemann, a work that he might have acquired through Pisendel. Bach would also have known Telemann well then since he was court musician at Eisenach, Bach's birthplace. Telemann's concerto for solo violin, TWV 51:g1, transcribed by Bach for harpsichord as BWV 985, comes from the same series of Eisenach concertos as the double violin concerto; moreover, as explained in Zohn (2008), there is evidence that the slow movement of Telemann's oboe concerto TWV 51:G2, also from the series, was borrowed and adapted by Bach for the opening sinfonia of the cantata Ich steh mit einem Fuß im Grabe, BWV 156 and the slow movement of the harpsichord concerto in F minor, BWV 1056, both dating from his period in Leipzig. Telemann also had a documented social connection with Bach: in March 1714 he was godparent at the baptism in Weimar of Bach's second son Carl Phillip Emanuel.[6]

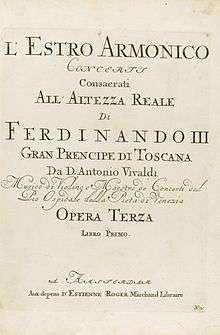

Later in July 1713, Prince Johann Ernst returned from Utrecht after studying there for 2 years. A keen amateur violinist, he is likely to have brought or sent back concerto scores from Amsterdam, probably including the collection L'estro armonico, Op.3 of Vivaldi, published there in 1711. Once back in Weimar, he studied composition with Walther, concentrating on the violin concerto. In July 1714, however, poor health forced him to leave Weimar to seek medical treatment in Bad Schwalbach: he died a year later at the age of nineteen. A number of his concertos were published posthumously by Telemann.[7]

Johann Ernst's enthusiasm for the concerto fitted well with Bach's own interests. It was under these circumstances that Bach, as composer and performer, made his virtuosic concerto transcriptions for organ (BWV 592–596) and for harpsichord (BWV 972–987 and BWV 592a). Although Bach served as Concertmaster in Weimar from 1714–1717, when he is presumed to have composed his own instrumental concertos, the only surviving works in Italian concerto-form from this period are his transcriptions of works by other composers. Of these, the main body were by Vivaldi, with others by Telemann, Alessandro and Benedetto Marcello and Johann Ernst himself. At the same time, Bach's cousin Walther also made a series of organ transcriptions of Italian concertos: in his autobiography, Walther mentions 78 such transcriptions; but of these only 14 survive, of concertos by Albinoni, Giorgio Gentili, Giulio Taglietti, Telemann, Torelli and Vivaldi. Bach and Walther arranged different sets of concertos: Bach favoured the more recent ritornello form, less prevalent in the earlier concertos transcribed by Walther.[8]

Schulze (1972) has given the following explanation for the transcriptions:[9]

Bach’s organ and harpsichord transcriptions BWV 592–596 and 972–987 belong to the year July 1713 to July 1714, were made at the request of Prince Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar, and imply a definite connection with the concert repertory played in Weimar and enlarged by the Prince’s recent purchases of music. Since the court concerts gave Bach an opportunity to know the works in their original form, the transcriptions are not so much study-works as practical versions and virtuoso 'commissioned' music.

.jpg)

Schulze has further suggested that during his two-year period studying in the Netherlands, Prince Johann Ernst is likely to have attended the popular concerts in the Niewe Kerk in Amsterdam where the blind organist Jan Jakob de Graaf performed his own transcriptions of the most recent Italian concertos. It is possible that this could have led to Johann Ernst to suggest similar concerto transcriptions to Bach and Walther. Other circumstantial evidence concerning music-making in Weimar is provided by a letter written by Bach's pupil Philipp David Kräuter in April 1713. Asking for permission to stay longer in Weimar, he states that Prince Johann Ernst,

who himself plays the violin incomparably, will return to Weimar from Holland after Easter and spend the summer here; I could then hear much fine Italian and French music, which would be particularly profitable to me in composing concertos and ouvertures ... I know too that when the new organ in Weimar is ready, Herr Bach will play incomparable things on it, especially at first ...

Kräuter's letter ties in with the organ repairs by Trebs made between June 1713 and May 1714. Commentators have found Schulze's arguments persuasive, but nevertheless point out that not all the transcriptions need have been made in the period from July 1713 to July 1714 when the Prince was back in Weimar. While this could be true for the simpler harpsichord transcriptions, some of the more virtuosic organ transcriptions could date from later, possible composed as a memorial to the prince, after his untimely death.[10]

Published records of Bach's life include his Nekrolog or obituary, written in 1754 by his son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and former pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola, and the 1802 biography of Johann Nikolaus Forkel. The Nekrolog contains the famous statement about the Duke, Wilhelm Ernst, encouraging Bach as an organist-composer, quoted at the start of this section. In the often quoted passage from his biography, Forkel wrote:[11]

J.S. Bach’s first attempts at composition, like all such efforts, were unsatisfactory. Lacking any instruction to point him towards his goal, he had to do what he could in his own way, like others who set out without a guide. Most beginning composers let their fingers run riot up and down the keyboard, snatching handfuls of notes, assaulting the instrument in an undisciplined way ... Such composers can only be "finger composers" (or "keyboard cavaliers" as Bach called them later on in his life): that is, they let their fingers tell them what to write instead of instructing their fingers what to play. Bach abandoned that method of composition when he observed that brilliant flourishes lead nowhere. He realised that musical ideas need to be subordinated to a plan and that a young composer's first need is a model to guide his efforts. Vivaldi's violin concertos, which had just been published, gave him the guidance he needed. He had often heard them praised for their artistic excellence and decided upon the happy idea of arranging them all for the clavier. He was thus led to study their structure, the musical ideas on which they are built, the pattern of their modulations, and many other characteristics. Moreover, in adapting ideas and figurations originally conceived for the violin to the keyboard, Bach was compelled to think in musical terms, so that his ideas no longer depended on his fingers, but were drawn from his imagination.

Although Forkel's account is generally acknowledged to be oversimplified and factually inaccurate, commentators agree that Bach's knowledge and assimilation of the Italian concerto form—which happened partly through his transcriptions—played a key role in the development of his mature style. In practical terms, the concerto transcriptions were suitable for performance in the different venues in Weimar; they would have served an educational purpose for the young prince as well as giving him pleasure.[12]

Marshall (1986) has carried out a systematic study of headings and markings in surviving manuscripts to ascertain the intended instrument for Bach's keyboard works. These have customarily been divided into two distinct groups, his works for organ and his works for harpsichord or clavichord. Although in early music the intended instrument was often not specified, but left to the performer, this was often not the case with Bach's music. Based on known manualiter settings within Bach's works for organ, the possible audience for performances of virtuosic keyboard compositions and the circumstances of their composition, Marshall has suggested that the concerto transcriptions BWV 972–987 might originally have been intended as manualiter settings for the organ.[13][14]

The reception of the concerto transcriptions is reflected in their transmission: they were less widely disseminated than Bach's original organ or keyoard works and were only published in the 1850s during the mid-nineteenth century Bach revival. More significantly perhaps, the concerto transcriptions played a decisive role in the Vivaldi revival which happened only in the following century. The meteoric success of Vivaldi in the early eighteenth century was matched by his descent into almost complete oblivion soon after his death in 1741. In Great Britain, France and particularly his native Italy, musical taste turned against him and, when he was remembered, it was just through salacious anecdote. Only in Northern Germany, where his concertos had influenced a school of composers, was his legacy properly appreciated. The publication of Bach's transcriptions has been recognized by Vivaldi scholars as a decisive step in his revival. In fact the new edition of the concerto transcriptions published by the Bach-Gesellschaft in the 1890s and the ensuing controversy in assessing their authorship and that of the original concertos in the 1910s sparked a reevaluation of Vivaldi and subsequently the rediscovery of his "lost" works.[15]

Although no precise dating of the concerto transcriptions is possible, combining a careful scientific analysis of surviving manuscripts—including their watermarks—with a knowledge of documented events in Bach's life has given a clearer idea of when they might have been written: it is generally thought that most were probably written in the period 1713–1714, but that some could have been written later. The transcriptions themselves became known through a variety of sources. The two most significant for dating purposes are the autograph manuscript of the organ transcription BWV 596; and the hand copies of the organ transcription BWV 592 and the harpsichord transcriptions BWV 972–982 made by Bach's second cousin Johann Bernhard Bach from Eisenach, who is known to have visited Weimar in May 1715. These include all the transcriptions of the Venetian concertos (those by Vivaldi and the Marcello brothers). The remaining organ transcriptions come from copies made in Leipzig by Bach's family and circle: these include his eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, whose organ repertoire included the transcriptions; his pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola; and Johann Peter Kellner. The other harpsichord transcriptions BWV 983–987 are contained in a collection of manuscripts of Kellner ("Kellner's Miscellany"), copied by himself and others.[16]

Transcriptions for organ, BWV 592–596

- Unless otherwise stated, the commentary on the transcriptions for organ is taken from Williams (2003).

These transcriptions for organ have been dated to 1713–1714. They are scored for two manual keyboards and pedal.[17]

Concerto in G major, BWV 592

This concerto is a transcription of a concerto by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar.

- [Allegro]

- Grave

- Presto

Concerto in A minor, BWV 593

This concerto is a transcription of a work by Antonio Vivaldi's double violin concerto, Op.3, No.8, RV 522.

- [Allegro]

- Adagio

- Allegro

Concerto in C major, BWV 594

This concerto is a transcription of Antonio Vivaldi's violin concerto "il grosso mogul," Op.7ii/5, RV 208.

- [Allegro]

- Recitativo Adagio

- Allegro

Concerto in C major, BWV 595

This concerto movement is a transcription of a composition by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar.

- Allegro

Concerto in D minor, BWV 596

- [Allegro]

- Pieno. Grave – Fuge

- Largo e spiccato

- [Allegro]

This transcription of Vivaldi's Concerto in D minor for two violins and obbligato violoncello, Op.3, No.11 (RV 565), had the heading on the autograph manuscript altered by Bach's son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach who added "di W. F. Bach manu mei Patris descript" sixty or more years later. The result was that up until 1911 the transcription was misattributed to Wilhelm Friedemann. Despite the fact that Carl Friedrich Zelter, director of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin where many Bach manuscripts were held, had suggested Johann Sebastian as the author, the transcription was first published as a work by Wilhelm Friedemann in 1844 in the edition prepared for C.F. Peters by Friedrich Griepenkerl. The precise dating and true authorship was later established from the manuscript: the handwriting and the watermarks in the manuscript paper conform to cantatas known to have been composed by Bach in Weimar in 1714–1715.

The autograph manuscript is remarkable for its detailed specifications of organ registration and use of the two manuals. As explained in Williams (2003), their main purpose was to enable the concerto to be heard at Bach's desired pitch. The markings are also significant for what they show about performance practise at that time: during the course of a single piece, hands could switch manuals and organ stops could be changed.[18]

First movement. From the outset in the original piece, Vivaldi creates an unusual texture: the two violins play as a duet and then are answered by a similar duet for obbligato cello and continuo bass. On the organ Bach creates his own musical texture by exchanging the solo parts between hands and having the responding duet on a second manual. For Williams (2003), Bach's redistribution of the constantly repeated quavers in the original is "no substitute for the lost rhetoric of the strings."[19]

Second movement. The dense chordal writing in the three introductory bars of the Grave is unusual and departs from Vivaldi's specification of "Adagio e spiccato". Bach adapted the fugue to the organ as follows: the pedal does not play the bass line of the original allegro but has an accompanying role, rather than being a separate voice in the fugue; the writing does not distinguish between soloists and ripieno; parts are frequently redistributed; and extra semiquaver figures are introduced, particularly over the prolonged pedal point concluding the piece. The resulting fugue is smoother than the original, which is distinguished by its clearly delineated sections. Williams (2003) remarks that the way Vivaldi inverts the fugue subject must have appealed to Bach.[20]

Third movement. The scoring for organ in the ritornello and solo episodes of this movement—a form of Siciliano—is unusual in Bach's writing for organ. The widely spaced chords that accompany the solo melody in the original are replaced by simple chords in the left hand. For Griepenkerl, the sweetness of the melody reflected the tender personality of Wilhelm Friedemann.[21]

Fourth movement. The last movement of Op.3, No.11 is composed in ritornello A–B–A form. In the opening bars the first and second violins play in tutti the opening theme with its repeated quavers and clashing dissonances. Bach used the same theme for the opening chorus of his cantata Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 21, first performed on 17 June 1714, shortly before ill health forced Prince Johann Ernst to leave Weimar for treatment in Bad Schwalbach.

Although each return of the theme with its chromatic falling bass accompaniment is instantly recognizable, Bach's allotting of parts between the two manuals (Oberwerk and Rückpositiv) can occasionally obscure Vivaldi's sharp distinction between solo and ripieno players. Various elements of Vivaldi's string writing, that would normally be outside Bach's musical vocabulary for organ compositions, are included directly or with slight adaptations in Bach's arrangement. As well as the dissonant suspensions in the opening quaver figures, these include quaver figures in parallel thirds, descending chromatic fourths, and rippling semidemiquavers and semiquavers in the left hand as an equivalent for the tremolo string accompaniment. Towards the end of the piece, Bach fills out the accompaniment in the final virtuosic semiquaver solo episode by adding imitative quaver figures in the lower parts. Williams (2003) compares the dramatic ending—with its chromatic fourths descending in the pedal part—to that of the keyboard Sinfonia in D minor, BWV 779.[22]

Transcriptions for harpsichord, BWV 972–987

Concerto in D major, BWV 972

After Violin Concerto in D major Op. 3 No. 9 (RV 230) by Antonio Vivaldi (there is an earlier version BWV 972a).

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Larghetto

- Allegro

Concerto in G major, BWV 973

After Violin Concerto in G major, RV 299, by Antonio Vivaldi (later version published as Op. 7 No. 8)

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Largo

- Allegro

Concerto in D minor, BWV 974

After Oboe Concerto in D minor by Alessandro Marcello[23]

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio

- Presto

Concerto in G minor, BWV 975

After Violin Concerto in G minor, RV 316, by Antonio Vivaldi (variant RV 316a, published as Op. 4 No. 6)

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Largo

- Giga Presto

Concerto in C major, BWV 976

After Violin Concerto in E major Op. 3 No. 12 (RV 265) by Antonio Vivaldi

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Largo

- Allegro

Concerto in C major, BWV 977

After an unidentified model

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio

- Giga

Concerto in F major, BWV 978

After Violin Concerto in G major Op. 3 No. 3 (RV 310) by Antonio Vivaldi

Movements:

- Allegro

- Largo

- Allegro

Concerto in B minor, BWV 979

After Violin Concerto in D minor, RV 813, by Antonio Vivaldi (formerly RV Anh. 10 attributed to Torelli)[24][25]

Movements:

- Allegro – Adagio

- Allegro

- Andante

- Adagio

- Allegro

Concerto in G major, BWV 980

After Violin Concerto in B-flat major, RV 383 by Antonio Vivaldi (variant RV 383a published as Op. 4 No. 1)

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Largo

- Allegro

Concerto in C minor, BWV 981

After Violin Concerto in C minor Op. 1 No. 2 by Benedetto Marcello

Movements:

- Adagio

- Vivace

- [no tempo indication]

- Prestissimo

Concerto in B-flat major, BWV 982

After Violin Concerto in B-flat major Op. 1 No. 1 by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio

- Allegro

- Allegro

Concerto in G minor, BWV 983

After an unidentified model

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio

- Allegro

Concerto in C major, BWV 984

After the Violin Concerto in C major by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe–Weimar (like BWV 595).

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio e affettoso

- Allegro assai

Concerto in G minor, BWV 985

After the Violin Concerto in G minor, TWV 51, by Georg Philipp Telemann.

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio

- Allegro

Concerto in G major, BWV 986

After an unidentified model

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Adagio

- Allegro

Concerto in D minor, BWV 987

After Concerto Op. 1 No. 4 by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar

Movements:

- [no tempo indication]

- Allegro

- Adagio

- Vivace

Notes

- ↑ See:

- Bach 2010, p. 25

- Williams 2003, p. 220

- ↑ David, Mendel & Wolff 1998

- ↑ See:

- Williams 2016, pp. 118–119

- Boyd 2001, p. 47

- ↑ See:

- ↑ Jones 2007, pp. 22–26, 40–42

- ↑ See;

- Jones 2007, pp. 140–141

- Bach 2010, p. 24

- Zohn 2008, pp. 124, 193–214

- Hirschmann 2013, pp. 22–23

- Hanks, GroveOnline

- ↑ See;

- Jones 2007, pp. 140–141

- Bach 2010, p. 24

- Hanks, GroveOnline

- ↑ See:

- Jones 2007, pp. 141–142

- Bach 2010, p. 24

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 202

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 203–204

- ↑ See:

- Forkel 1920, pp. 70–71 The translation in the text follows Terry's translation with some slight modifications

- Talbot 1993, pp. 2–3

- ↑ See:

- Jones 2007, p. 235

- Williams 2003, pp. 203–204

- Breig 1997b, p. 164

- Boyd 2001, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Marshall 1986, pp. 212–232

- ↑ Bach 2010, pp. 25–26 Dirksen takes issue with Marshall's suggestion on stylistic grounds, starting from the fact that the two arrangements of one of Prince Johann Ernst's concertos, BWV 592 and 592a, are explicitly designated for organ and cembalo.

- ↑ See:

- Bach 2010, pp. 24–25

- Pincherle 1962

- Talbot 1993

- Brover-Lubovsky 2008

- ↑ See:

- Bach 2010, pp. 24–25

- Williams 2016

- Schulenberg 2006, pp. 118–119

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 201–226

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 220–224

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 221–222

- ↑ Williams 2003, pp. 222–223

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 223

- ↑ Williams 2003, p. 223–224

- ↑ Selfridge-Field, D935

- ↑ Talbot, 2011. RV813

- ↑ Schulenberg, 2016

References

- Bach, J.S. (2010), Dirksen, Pieter, ed., Sonatas, Trios, Concertos, Complete Organ Works (Breitkopf Urtext), vol.5 EB 8805, Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, ISMN 979-0-004-18366-3 Introduction (in German and English) • Commentary (English translation—commentary in paperback original is in German)

- Boyd, Malcolm (2007), Bach, Master Musician Series, Oxford University Press, pp. 80–83, ISBN 9780195307719

- Breig, Werner (1997a), "The Instrumental Music", in John Butt, The Cambridge Companion to Bach, pp. 123–135, ISBN 9781139002158

- Breig, Werner (1997b), "Composition as arrangement and adaptation", in John Butt, The Cambridge Companion to Bach, pp. 154–170, ISBN 9781139002158

- Brover-Lubovsky, Bella (2008), Tonal Space in the Music of Antonio Vivaldi, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253351294

- Butler, H. Joseph (2011), "Emulation and Inspiration: J. S. Bach’s Transcriptions from Vivaldi’s L’estro armonico" (PDF), The Diapason: 19–21

- David, Hans Theodore; Mendel, Arthur; Wolff, Christoph (1998), The New Bach Reader (Revised ed.), W.W. Norton, ISBN 0393319563]

- Forkel, Johann Nikolaus (1920), Charles Sanford Terry (historian), ed., Johann Sebastian Bach: His Life, Art, and Work, Harcourt, Brace and Howe

- Hanks, Sarah E. "Johann Ernst, Prince of Weimar". In L. Root, Deane. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 January 2017. (subscription required)

- Hirschmann, Wolfgang (2013), "'He Liked to Hear the Music of Others': Individuality and Variety in the Works of Bach and His German Contemporaries", in Andrew Talle, Bach Perspectives, Volume 9: J.S. Bach and His Contemporaries in Germany, University of Illinois Press, pp. 1–23, ISBN 0252095391

- Jones, Richard (1997), "The keyboard works: Bach as teacher and virtuoso", in John Butt, The Cambridge Companion to Bach, Cambridge University Press, pp. 136–153, ISBN 9780521587808

- Jones, Richard (2007), The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach: Music to Delight the Spirit, Volume I: 1695-1717, Oxford University Press, pp. 140–153, ISBN 9780198164401

- Jones, Richard (2013), The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach: Music to Delight the Spirit, Volume II: 1717-1750, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780191503849

- Marshall, Robert (1986), "Organ or 'Klavier'? Instrumental prescriptions in the sources of Bach's keyboard works", in George Stauffer; Ernest May, J.S. Bach as Organist, Indiana University Press, pp. 212–239

- Pincherle, Marc (1962), Vivaldi: Genius of the Baroque, translated by Christopher Hatch, W.W. Norton, ISBN 0393001687

- Schulenberg, David (2013), The Keyboard Music of J.S. Bach, Routledge, pp. 117–139, ISBN 9781136091469, Updates (2016)

- Schulze, Hans-Joachim (1978), "J. S. Bachs Konzertbearbeitungen nach Vivaldi und anderen: Studien- oder Auftragswerke?", Deutsches Jahrbuch der Musikwissenschaft für 1973–1977, Leipzig, pp. 80–100

- Selfridge-Field, Eleanor (1990), The Music of Benedetto and Alessandro Marcello: A Thematic Catalogue with Commentary on the Composers, Repertory, and Sources, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780193161269

- Stevens, Jane R. (2001), The Bach Family and the Keyboard Concerto: The Evolution of a Genre, Harmonie Park Press

- Tagliavini, Luigi Ferdinando (1986), "Bach's organ transcription of Vivaldi's 'Grosso Mogul' concerto", in George Stauffer; Ernest May, J.S. Bach as Organist, Indiana University Press, pp. 240–255

- Talbot, Michael (1993), Vivaldi, The Master Musicians (2nd ed.), J.M. Dent, ISBN 0460861085

- Talbot, Michael, ed. (2011), The Vivaldi Compendium, Boydell Press, ISBN 9781843836704

- Williams, Peter (2003), The Organ Music of J. S. Bach (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 201–224, ISBN 0-521-89115-9

- Williams, Peter (2016), Bach: A Musical Biography, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107139251

- Wolff, Christoph (1994), "Bach's Leipzig Chamber Music", Bach: Essays on His Life and Work, Harvard University Press, p. 263, ISBN 0674059263 (a reprint of a 1985 publication in Early Music)

- Wolff, Christoph (2001), Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician, W. W. Norton, ISBN 9780393322569

- Zohn, Steven (2008), Music for a Mixed Taste: Style, Genre, and Meaning in Telemann's Instrumental Works, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0190247851

External links

- Scores are available at IMSLP