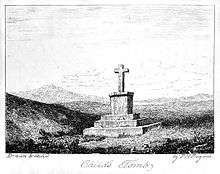

Childe's Tomb

Childe's Tomb is a granite cross on Dartmoor, Devon, England. Although not in its original form, it is more elaborate than most of the crosses on Dartmoor, being raised upon a constructed base, and it is known that a kistvaen is underneath.

A well-known legend attached to the site, first recorded in 1630 by Tristram Risdon, concerns a wealthy hunter, Childe, who became lost in a snow storm and supposedly died there despite disembowelling his horse and climbing into its body for protection. The legend relates that Childe left a note of some sort saying that whoever found and buried his body would inherit his lands at Plymstock. After a race between the monks of Tavistock Abbey and the men of Plymstock, the Abbey won.

The tomb was virtually destroyed in 1812 by a man who stole most of the stones to build a house nearby, but it was partly reconstructed in 1890.

Description

Childe's Tomb is a reconstructed granite cross on the south-east edge of Foxtor Mires, about 500 metres north of Fox Tor on Dartmoor, Devon, England at grid reference SX625704. According to William Burt, in his notes to Dartmoor, a Descriptive Poem by N. T. Carrington (1826), the original tomb consisted of a pedestal of three steps, the lowest of which was built of four stones each six feet long and twelve inches square. The two upper steps were made of eight shorter but similarly shaped stones, and on top was an octagonal block about three feet high with a cross fixed upon it.[1]

The tomb lies on the line of several cairns that marked the east-west route of the ancient Monks' Path between Buckfast Abbey and Tavistock Abbey and it was no doubt erected here as part of that route: it would have been particularly useful in this part of the moor with few landmarks where a traveller straying from the path could easily end up in Foxtor Mires.[2] Tristram Risdon, writing in about 1630, said that Childe's Tomb was one of three remarkable things in the Forest of Dartmoor (the others being Crockern Tor and Wistman's Wood).[3] Risdon also stated that the original tomb bore an inscription: "They fyrste that fyndes and bringes mee to my grave, The priorie of Plimstoke they shall have",[4] but no sign of this has ever been found.

Today the cross, which is a replacement, is about 3 feet 4 inches (1.02 m) tall and 1 foot 8 inches (0.51 m) across at the crosspiece, and it has its base in a socket stone which rests on a pedestal of granite blocks that raises the total height of the cross to 7 ft (2.1 m). The original, now broken, socket stone for the cross lies nearby. The whole is surrounded by a circle of granite stones set on their edge which once surrounded the cairn—the rocks of which are now scattered around—that was originally built over a large kistvaen that still exists beneath the pedestal.[2]

Destruction

In the early 19th century there was much interest in enclosing and "improving" the open moorland on Dartmoor, encouraged by Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt's early successes at Tor Royal near Princetown.[5] Enclosure was aided by the greatly enhanced access provided by the construction of the first turnpike roads over the moor: the road between Ashburton and Two Bridges opened in around 1800, for instance.[6] In February 1809 one Thomas Windeatt, from Bridgetown, Totnes, took over the lease of a plot of land (a "newtake") of about 582 acres in the valley of the River Swincombe. In 1812 Windeatt started to build a farmhouse, Fox Tor Farm, on his land and his workmen robbed the nearby Childe's Tomb of most of its stones for the building and its doorsteps.[7][8]

In 1902 William Crossing wrote that he had been told by an old moorman that some of the granite blocks from the tomb's pedestal had also been used to make a clapper bridge across a stream flowing into the River Swincombe near the farm. The moorman also said that they had lettering on their undersides.[9] This encouraged Crossing to arrange to lift the clapper bridge, but no inscription was found. However, he did locate nine out of the twelve stones that had made up the pedestal, as well as the broken socket stone for the cross.[7]

Reconstruction

Crossing rediscovered the original site of the tomb in 1882 and said that all that remained was a small mound and some half buried stones. He cleared out the kistvaen, reporting that it was 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) long by 2 feet 8 inches (81 cm) wide and that unlike most kistvaens found on the moor, the stones lining it had apparently been shaped by man, which led him to suggest that it was less old than most.[10] Having located most of the stones of the original tomb, Crossing thought that it could be rebuilt in its original form with little effort, but it was not to be.[11]

J. Brooking Rowe, writing in 1895, states that the tomb was re-erected in 1890 under the direction of Mr. E. Fearnley Tanner, who said that he was dissatisfied with the result because several stones were missing and it was difficult to recreate the original character of the monument.[12] Tanner was the honourable secretary of the Dartmoor Preservation Association,[13] and this reconstruction was one of the first acts of that organisation. The replacement base and cross were made in Holne in 1885.[13]

Childe the Hunter

According to legend, the cross was erected over the kistvaen (burial chamber) of Childe the Hunter, who was Ordulf, son of Ordgar, an Anglo-Saxon Earl of Devon in the 11th century. The name Childe is probably derived from the Old English word cild which was used as a title of honour.[14]

Legend has it that Childe was in a party hunting on the moor when they were caught in some changeable weather. Childe became separated from the main party and was lost. In order to save himself from dying of exposure, he killed his horse, disembowelled it and crept inside the warm carcass for shelter. He nevertheless froze to death, but before he died, he wrote a note to the effect that whoever should find him and bury him in their church should inherit his Plymstock estate.

His body was found by the monks of Tavistock Abbey, who started to carry it back. However, they heard of a plot to ambush them by the people of Plymstock, at a bridge over the River Tavy. They took a detour and built a new bridge over the river, just outside Tavistock. They were successful in burying the body in the grounds of the Abbey and inherited the Plymstock estate.

The first account of this story is to be found in Risdon's Survey of Devon which was completed in around 1632:

It is left us by tradition that one Childe of Plimstoke, a man of fair possessions, having no issue, ordained, by his will, that wheresoever he should happen to be buried, to that church his lands should belong. It so fortuned, that he riding to hunt in the forest of Dartmore, being in pursuit of his game, casually lost his company, and his way likewise. The season then being so cold, and he so benumed therewith, as he was enforced to kill his horse, and embowelled him, to creep into his belly to get heat; which not able to preserve him, was there frozen to death; and so found, was carried by Tavistoke men to be buried in the church of that abbey; which was so secretly done but the inhabitants of Plymstoke had knowledge thereof; which to prevent, they resorted to defend the carriage of the corpse over the bridge, where, they conceived, necessity compelled them to pass. But they were deceived by guile; for the Tavistoke men forthwith built a slight bridge, and passed over at another place without resistance, buried the body, and enjoyed the lands; in memory whereof the bridge beareth the name of Guilebridge to this day.[4]

Finberg pointed out, however, that a document of 1651 refers to Tavistock's guildhall as Guilehall, so Guilebridge is more likely to be guild bridge, probably because it was built or maintained by one of the town guilds.[14]

In popular culture

Devon folk singer Seth Lakeman sang about Childe the Hunter on his 2006 album Freedom Fields.

References

- ↑ Reported by Crossing (1902) p. 89

- 1 2 Butler, Jeremy (1993). Dartmoor Atlas of Antiquities, Volume 4: The South-East. Exeter: Devon Books. pp. 218–20. ISBN 0-86114-881-9.

- ↑ Risdon (1811) pp. 222–3

- 1 2 Risdon (1811) pp. 198–9

- ↑ Rowe (1985) p. 255

- ↑ Mercer, Ian (2009). Dartmoor - A Statement of its Time. London: Collins. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-00-718499-6.

- 1 2 Stanbrook (1994) p. 42–3

- ↑ Sandles, Tim. "Childe the Hunter". www.legendarydartmoor.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Crossing (1902) p. 93

- ↑ Crossing (1902) p. 91

- ↑ Crossing (1902) pp. 93–4

- ↑ Rowe (1985) pp. 188–9

- 1 2 Stanbrook (1994) p. 44

- 1 2 Finberg (1946) p. 277

Sources

- Crossing, William (1902). The Ancient Stone Crosses of Dartmoor and its Borderland. Exeter: James G. Commin. pp. 88–97.

- H. P. R. Finberg (1946). "Childe's Tomb". Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association. 78: 265–280.

- Risdon, Tristram (1811) [c. 1632]. Rees; et al., eds. The Chorographical Description or Survey of the County of Devon (updated ed.). Plymouth: Rees and Curtis.

- Rowe, Samuel; Rowe, J. Brooking (1985) [1896]. A Perambulation of the Forest of Dartmoor (reprint of 3rd ed.). Exeter: Devon Books. ISBN 0-86114-773-1.

- Stanbrook, Elisabeth (1994). Dartmoor Forest Farms - A Social History from Enclosure to Abandonment. Tiverton: Devon Books. pp. 42–44. ISBN 0-86114-887-8.

Coordinates: 50°31′02″N 3°56′27″W / 50.51719°N 3.94085°W