Opus Anglicanum

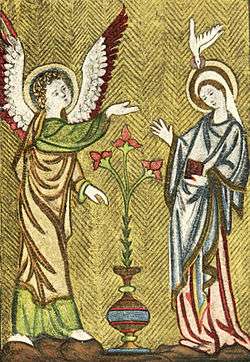

Opus Anglicanum or English work is fine needlework of Medieval England done for ecclesiastical or secular use on clothing, hangings or other textiles, often using gold and silver threads on rich velvet or linen grounds. Such English embroidery was in great demand across Europe, particularly from the late 12th to mid-14th centuries and was a luxury product often used for diplomatic gifts.

Uses

Most of the surviving examples of Opus Anglicanum were designed for liturgical use. These exquisite and expensive embroidery pieces were often made as vestments, such as copes, chasubles and orphreys, or else as antependia, shrine covers or other church furnishings. Secular examples, now known mostly just from contemporary inventories, included various types of garments, horse-trappings, book covers and decorative hangings.

Manufacture

Opus Anglicanum was usually embroidered on linen or, later, velvet, in split stitch and couching with silk and gold or silver-gilt thread.[2] Gold-wound thread, pearls and jewels are all mentioned in inventory descriptions. Although often associated with nunneries, by the time of Henry III (reg. 1216–72), who purchased a number of items for use within his own court and for diplomatic gifting, the bulk of production was in lay workshops, mainly centred on London. The names of various (male) embroiderers of the period appear in the Westminster royal accounts.[3]

Reputation

English needlework had become famous across Europe during the Anglo-Saxon period (though very few examples survive) and remained so throughout the Gothic era. A Vatican inventory of 1295 lists over 113 pieces from England, more than from any other country;[4] a request by Pope Innocent IV, who had envied the gold-embroidered copes and mitres of English priests, that Cistercian religious houses send more is reported by the Benedictine chronicler Matthew Paris of St Albans: "This command of my Lord Pope did not displease the London merchants who traded in these embroideries and sold them at their own price."[5] The high water mark of style and refinement is normally considered to have been reached in the work of the 13th and early 14th centuries. An influential exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum from September–November 1963 displayed several examples of Opus Anglicanum from this period alongside contemporary works of wood and stone sculpture, metalwork and ivories.[6]

Examples

Survival rates for Opus Anglicanum are low (especially for secular works) as is clear from comparing the large number listed in contemporary inventories with the handful of examples still existing. Sometimes ecclesiastical garments were later modified for different uses, such as altar coverings or book covers. Others were buried with their owners, as with the vestments of the mid-13th century Bishops, Walter de Cantilupe and William de Blois, fragments of which were recovered when their tombs in Worcester Cathedral were opened in the 18th century. The majority however were lost to neglect, destroyed by iconoclasts or else unpicked or burnt to recover the precious metals from the gold and silver threads. Although fragmentary examples can be found in a number of museums, the most important specialised collections of Opus Anglicanum garments are at the Cloisters Museum in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and in the Treasury of Sens Cathedral.

Only a few Anglo-Saxon pieces have survived, including three pieces at Durham that had been placed in the coffin of St Cuthbert, probably in the 930s, after being given by King Athelstan; they were however made in Winchester between 909 and 916. These are works "of breathtaking brilliance and quality", according to Wilson, including figures of saints, and important early examples of the Winchester style, though the origin of their style is a puzzle; they are closest to a wall-painting fragment from Winchester, and an early example of acanthus decoration.[7] The earliest group of survivals, now re-arranged and with the precious metal thread mostly picked out, are bands or borders from vestments, incorporating pearls and glass beads, with various types of scroll and animal decoration. These are probably 9th century and now in a church in Maaseik in Belgium.[8] A further style of textile is a vestment illustrated in a miniature portrait of Saint Aethelwold in his Benedictional, which shows the edge of what appears to be a huge acanthus "flower" (a term used in several documentary records) covering the wearer's back and shoulders. Other written sources mention other large-scale compositions.[9]

One particularly fine example is The Adoration of the Magi chasuble from c. 1325 in red velvet embroidered in gold thread and pearls at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It depicts a nativity scene with emphasis on decorative motifs, flowers, animals, birds, beasts, and angels. The Butler-Bowden Cope at the Victoria and Albert Museum is another surviving example; the same collection has a late cope made for a set of vestments given by Henry VII to Westminster Abbey.

Notes

- ↑ Davenport, Cyril, English Embroidered Bookbindings, edited by Alfred Pollard, London, 1899

- ↑ Levey, S. M. and D. King, The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection Vol. 3: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1993, ISBN 1-85177-126-3

- ↑ Article: Opus Anglicanum, Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford, 1996

- ↑ Remnant 1964:111; Bonnie Young, "Opus Anglicanum" The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, 29.7 (March 1971:291–298) p. 291; the article was occasioned by an exhibition at The Cloisters.

- ↑ Quoted Young 1971:291.

- ↑ King, David (ed), Opus Anglicanum (exhibition catalogue), London, V&A Press, 1963.

- ↑ Wilson, 154–156, quote 155; Dodwell (1993), 26; Golden Age, 19, 44, though neither these nor any textiles could be lent for the exhibition.

- ↑ Wilson, 108; Dodwell (1993), 27, who gives details of further fragments.

- ↑ Dodwell (1982), 183–185; portrait of Saint Aethelwold

References

- Davenport, Cyril, English Embroidered Bookbindings, edited by Alfred Pollard, London, 1899 (

- English Embroidered Bookbindings at Project Gutenberg)

- "Dodwell (1982)": Dodwell, C. R., Anglo-Saxon Art, A New Perspective, 1982, Manchester UP, ISBN 0-7190-0926-X

- "Dodwell (1993)": Dodwell, C. R., The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- "Golden Age": Backhouse, Janet, Turner, D.H., and Webster, Leslie, eds.; The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art, 966–1066, 1984, British Museum Publications Ltd, ISBN 0-7141-0532-5

- Levey, S. M. and D. King, The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection Vol. 3: Embroidery in Britain from 1200 to 1750, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1993, ISBN 1-85177-126-3

- Wilson, David M.; Anglo-Saxon: Art From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, Thames and Hudson (US edn. Overlook Press), 1984.

Further reading

- King, Donald: Opus Anglicanum: English Medieval Embroidery, London: HMSO, 1963.

- Christie, A.G.I: English Medieval Embroidery, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1938.

- Staniland, K: Medieval Craftsmen: Embroiderers, London: British Museum Press, 1991.

- Michael, M.A: The Age of Opus Anglicanum (London, Harvey Miller/Brepols, 2016.

- Browne C., Davies, G & Michael, M.A: English Meidieval Embroidery, Opus Anglicanum, London and New Haven, Yale University Press, 2016.

External links

- Opus Anglicanum at Historical Needlework

- Opus Anglicanum: English Work, or How to Paint With a Needle

- Medieval English embroidery at the Victoria and Albert Museum website

- Chasuble in Opus Anglicanum, Metropolitan Museum of Art