Optic chiasm

| Optic chiasma | |

|---|---|

Brain viewed from below; the front of the brain is above. Visual pathway with optic chiasm (X shape) is shown in red (1543 image from Andreas Vesalius' Fabrica) | |

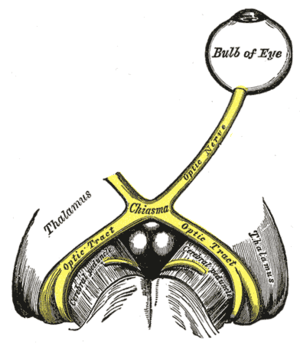

Optic nerves, chiasm, and optic tracts | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Visual system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | chiasma opticum |

| MeSH | A08.800.800.120.680.600 |

| NeuroLex ID | Optic chiasm |

| TA | A14.1.08.403 |

| FMA | 62045 |

The optic chiasm or optic chiasma ( /ɒptɪk kaɪæzəm/; Greek χίασμα, "crossing", from the Greek χιάζω 'to mark with an X', after the Greek letter 'Χ', chi) is the part of the brain where the optic nerves partially cross. The optic chiasm is located at the bottom of the brain immediately below the hypothalamus.[1] The optic chiasm is found in all vertebrates, although in cyclostomes (lampreys and hagfishes) it is located within the brain.[2][3]

Structure

The optic nerve fibres on the nasal sides of each retina cross over (decussate) to the opposite side of the brain via the optic nerve at the optic chiasm (decussation of medial fibers). The temporal hemiretina, on the other hand, stays on the same side. The inferonasal retina are related to anterior portion of the optic chiasm whereas superonasal retinal fibers are related to the posterior portion of the optic chiasm.

The crossing over of optic nerve fibres at the optic chiasm allows the visual cortex to receive the same hemispheric visual field from both eyes. Superimposing and processing these monocular visual signals allow the visual cortex to generate binocular and stereoscopic vision. For example, the right visual cortex receives the temporal visual field from the left eye, and the nasal visual field from the right eye, which results in the right visual cortex producing a binocular image of the left hemispheric visual field. The net result of optic nerve crossing over at the optic chiasm is for the right cerebral hemisphere to sense and process left hemispheric vision, and for the left cerebral hemisphere to sense and process right hemispheric vision.[4]

This crossing is an adaptive feature of frontally oriented eyes, found mostly in predatory animals requiring precise visual depth perception. (Prey animals, with laterally positioned eyes, have little binocular vision, so there is a more complete crossover of visual signals.) Beyond the optic chiasm, with crossed and uncrossed fibers, the optic nerves become optic tracts. The signals are passed on to the lateral geniculate body, in turn giving them to the occipital cortex (the outer matter of the rear brain).[5]

Other animals

In Siamese cats with certain genotypes of the albino gene, this wiring is disrupted, with more of the nerve-crossing than is normal, as a number of scholars have reported.[6] To compensate for lack of crossing in their brains, they cross their eyes (strabismus).[7]

This is also seen in albino tigers, as Guillery & Kaas report.[8]

Additional images

Scheme showing central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts.

Scheme showing central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts. Base of brain.

Base of brain. 3D schematic representation of optic tracts

3D schematic representation of optic tracts- Human brainstem anterior view

- Optic chiasm

- Optic chiasma

- Cerebrum.Inferior view.Deep dissection.

- Cerebrum.Inferior view. Deep dissection.

History

The crossing of nerve fibres, and the impact on vision that this had, was probably first identified by Persian physician "Esmail Jorjani", who appears to be Zayn al-Din Gorgani (1042-1137).[9]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Optic chiasm. |

References

- ↑ Colman, Andrew M. (2006). Oxford Dictionary of Psychology (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 530. ISBN 0-19-861035-1.

- ↑ Bainbridge, David (30 June 2009). Beyond the Zonules of Zinn: A Fantastic Journey Through Your Brain. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-674-02042-9. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ de Lussanet, Marc H.E.; Osse, Jan W.M. (2012). "An ancestral axial twist explains the contralateral forebrain and the optic chiasm in vertebrates". Animal Biology. 62 (2): 193–216. ISSN 1570-7555. arXiv:1003.1872

. doi:10.1163/157075611X617102.

. doi:10.1163/157075611X617102. - ↑ Purves, Dale; Augustine, George; Fitzpatrick, David; Hall, William; LaMantia, Anthony-Samuel; White, Leonard (2012). Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- ↑ "eye, human." Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009

- ↑ Schmolesky MT, Wang Y, Creel DJ, Leventhal AG. "Abnormal retinotopic organization of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the tyrosinase-negative albino cat.". J Comp Neurol. 427 (2): 209–19. PMID 11054689. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20001113)427:2<209::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-3.

- ↑ Guillery, RW; Kaas, JH (June 1973). "Genetic abnormality of the visual pathways in a "white" tiger". Science. 180 (4092): 1287–9. Bibcode:1973Sci...180.1287G. PMID 4707916. doi:10.1126/science.180.4092.1287.

- ↑ Guillery RW (May 1974). "Visual pathways in albinos". Sci. Am. 230 (5): 44–54. PMID 4822986. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0574-44.

- ↑ Davis, Matthew C.; Griessenauer, Christoph J.; Bosmia, Anand N.; Tubbs, R. Shane; Shoja, Mohammadali M. (2014-01-01). "The naming of the cranial nerves: A historical review". Clinical Anatomy. 27 (1): 14–19. ISSN 1098-2353. doi:10.1002/ca.22345.

- Jeffery G (October 2001). "Architecture of the optic chiasm and the mechanisms that sculpt its development". Physiol. Rev. 81 (4): 1393–414. PMID 11581492.

External links

- "Anatomy diagram: 13048.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.