Open data

Open data is the idea that some data should be freely available to everyone to use and republish as they wish, without restrictions from copyright, patents or other mechanisms of control.[1] The goals of the open data movement are similar to those of other "open" movements such as open source, open hardware, open content, open government and open access. The philosophy behind open data has been long established (for example in the Mertonian tradition of science), but the term "open data" itself is recent, gaining popularity with the rise of the Internet and World Wide Web and, especially, with the launch of open-data government initiatives such as Data.gov and Data.gov.uk.

Overview

The concept of open data is not new; but a formalized definition is relatively new. One definition is the Open Definition which can be summarized in the statement that "A piece of data is open if anyone is free to use, reuse, and redistribute it – subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and/or share-alike."[2] Other definitions, including the Open Data Institute's "Open data is data that anyone can access, use or share", have an accessible short version of the definition but refer to the formal definition.

Open data may include non-textual material such as maps, genomes, connectomes, chemical compounds, mathematical and scientific formulae, medical data and practice, bioscience and biodiversity. Problems often arise because these are commercially valuable or can be aggregated into works of value. Access to, or re-use of, the data is controlled by organisations, both public and private. Control may be through access restrictions, licenses, copyright, patents and charges for access or re-use. Advocates of open data argue that these restrictions are against the common good and that these data should be made available without restriction or fee. In addition, it is important that the data are re-usable without requiring further permission, though the types of re-use (such as the creation of derivative works) may be controlled by a license.

A typical depiction of the need for open data:

Numerous scientists have pointed out the irony that right at the historical moment when we have the technologies to permit worldwide availability and distributed process of scientific data, broadening collaboration and accelerating the pace and depth of discovery ... we are busy locking up that data and preventing the use of correspondingly advanced technologies on knowledge.— John Wilbanks, VP Science, Creative Commons[3]

Creators of data often do not consider the need to state the conditions of ownership, licensing and re-use; instead presuming that not asserting copyright puts the data into the public domain. For example, many scientists do not regard the published data arising from their work to be theirs to control and consider the act of publication in a journal to be an implicit release of data into the commons. However, the lack of a license makes it difficult to determine the status of a data set and may restrict the use of data offered in an "Open" spirit. Because of this uncertainty it is also possible for public or private organizations to aggregate said data, protect it with copyright and then resell it.

The issue of indigenous knowledge (IK) poses a great challenge in terms of capturing, storage and distribution. Many societies in third-world countries lack the technicality processes of managing the IK.

At his presentation at the XML 2005 conference, Connolly[4] displayed these two quotations regarding open data:

- "I want my data back." (Jon Bosak circa 1997)

- "I've long believed that customers of any application own the data they enter into it."[5] (This quote refers to Veen's own heart-rate data.)

Major sources

Open data can come from any source. This section lists some of the fields that publish (or at least discuss publishing) a large amount of open data.

In science

The concept of open access to scientific data was institutionally established with the formation of the World Data Center system, in preparation for the International Geophysical Year of 1957–1958.[6] The International Council of Scientific Unions (now the International Council for Science) established several World Data Centers to minimize the risk of data loss and to maximize data accessibility, further recommending in 1955 that data be made available in machine-readable form.[7]

While the open-science-data movement long predates the Internet, the availability of fast, ubiquitous networking has significantly changed the context of Open science data, since publishing or obtaining data has become much less expensive and time-consuming.

The Human Genome Project was a major initiative that exemplified the power of open data. It was built upon the so-called Bermuda Principles, stipulating that: "All human genomic sequence information (…) should be freely available and in the public domain in order to encourage research and development and to maximise its benefit to society'.[8] More recent initiatives such as the Structural Genomics Consortium have illustrated that the open data approach can also be used productively within the context of industrial R&D.[9]

In 2004, the Science Ministers of all nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which includes most developed countries of the world, signed a declaration which essentially states that all publicly funded archive data should be made publicly available.[10] Following a request and an intense discussion with data-producing institutions in member states, the OECD published in 2007 the OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding as a soft-law recommendation.[11]

Examples of open data in science:

- The Dataverse Network Project – archival repository software promoting data sharing, persistent data citation, and reproducible research[12]

- data.uni-muenster.de –b Open data about scientific artifacts from University of Muenster, Germany. Launched in 2011.

- linkedscience.org/data – Open scientific datasets encoded as Linked Data. Launched in 2011.

In Government

There are a range of different arguments for Government Open Data.[13][14] For example, some advocates contend that making government information available to the public as machine readable open data can facilitate government transparency, accountability and public participation. Some make the case that opening up official information can support technological innovation and economic growth by enabling third parties to develop new kinds of digital applications and services.

Several national governments have created web sites to distribute a portion of the data they collect. It is a concept for a collaborative project in municipal Government to create and organize culture for Open Data or Open government data.

Additionally, other levels of government have established open data websites. There are many government entities pursuing Open Data in Canada. Data.gov lists the sites of a total of 40 US states and 46 US cities and counties with web sites to provide open data; e.g. the state of Maryland, the state of California, US.[15]

At the international level, the United Nations has an open data website that publishes statistical data from Member States and UN Agencies,[16] and The World Bank published a range of statistical data relating to developing countries.[17] The European Commission has created two portals for the European Union: the EU Open Data Portal which gives access to open data from the EU institutions, agencies and other bodies[18] and the PublicData portal that provides datasets from local, regional and national public bodies across Europe.[19]

In October 2015, the Open Government Partnership launched the International Open Data Charter, a set of principles and best practices for the release of governmental open data formally adopted by seventeen governments of countries, states and cities during the OGP Global Summit in Mexico.[20]

Arguments for and against

The debate on Open Data is still evolving. The best open government applications seek to empower citizens, to help small businesses, or to create value in some other positive, constructive way. Opening government data is only a way-point on the road to improving education, improving government, and building tools to solve other real world problems. While many arguments have been made categorically, the following discussion of arguments for and against open data highlights that these arguments often depend highly on the type of data and its potential uses.

Arguments made on behalf of Open Data include the following:

- "Data belong to the human race". Typical examples are genomes, data on organisms, medical science, environmental data following the Aarhus Convention

- Public money was used to fund the work and so it should be universally available.[21]

- It was created by or at a government institution (this is common in US National Laboratories and government agencies)

- Facts cannot legally be copyrighted.

- Sponsors of research do not get full value unless the resulting data are freely available.

- Restrictions on data re-use create an anticommons.

- Data are required for the smooth process of running communal human activities and are an important enabler of socio-economic development (health care, education, economic productivity, etc.).[22]

- In scientific research, the rate of discovery is accelerated by better access to data.[23]

- Making data open helps combat "data rot" and ensure that scientific research data are preserved over time.[24][25]

It is generally held that factual data cannot be copyrighted.[26] However, publishers frequently add copyright statements (often forbidding re-use) to scientific data accompanying publications. It may be unclear whether the factual data embedded in full text are part of the copyright.

While the human abstraction of facts from paper publications is normally accepted as legal there is often an implied restriction on the machine extraction by robots.

Unlike Open Access, where groups of publishers have stated their concerns, Open Data is normally challenged by individual institutions. Their arguments have been discussed less in public discourse and there are fewer quotes to rely on at this time.

Arguments against making all data available as Open Data include the following:

- Government funding may not be used to duplicate or challenge the activities of the private sector (e.g. PubChem).

- Governments have to be accountable for the efficient use of taxpayer's money: If public funds are used to aggregate the data and if the data will bring commercial (private) benefits to only a small number of users, the users should reimburse governments for the cost of providing the data.

- The revenue earned by publishing data can be used to cover the costs of generating and/or disseminating the data, so that the dissemination can continue indefinitely.

- The revenue earned by publishing data permits non-profit organisations to fund other activities (e.g. learned society publishing supports the society).

- The government gives specific legitimacy for certain organisations to recover costs (NIST in US, Ordnance Survey in UK).

- Privacy concerns may require that access to data is limited to specific users or to sub-sets of the data.

- Collecting, 'cleaning', managing and disseminating data are typically labour- and/or cost-intensive processes – whoever provides these services should receive fair remuneration for providing those services.

- Sponsors do not get full value unless their data is used appropriately – sometimes this requires quality management, dissemination and branding efforts that can best be achieved by charging fees to users.

- Often, targeted end-users cannot use the data without additional processing (analysis, apps etc.) – if anyone has access to the data, none may have an incentive to invest in the processing required to make data useful (typical examples include biological, medical, and environmental data).

Relation to other open activities

The goals of the Open Data movement are similar to those of other "Open" movements.

- Open access is concerned with making scholarly publications freely available on the internet. In some cases, these articles include open datasets as well.

- Open content is concerned with making resources aimed at a human audience (such as prose, photos, or videos) freely available.

- Open knowledge. Open Knowledge International argues for Openness in a range of issues including, but not limited to, those of Open Data. It covers (a) scientific, historical, geographic or otherwise (b) Content such as music, films, books (c) Government and other administrative information. Open data is included within the scope of the Open Knowledge Definition, which is alluded to in Science Commons' Protocol for Implementing Open Access Data.[27]

- Open notebook science refers to the application of the Open Data concept to as much of the scientific process as possible, including failed experiments and raw experimental data.[28]

- Open source (software) is concerned with the licenses under which computer programs can be distributed and is not normally concerned primarily with data.

- Open educational resources are freely accessible, openly licensed documents and media that are useful for teaching, learning, and assessing as well as for research purposes.

- Open research/Open science/Open science data (Linked open science) means an approach to open and interconnect scientific assets like data, methods and tools with Linked Data techniques to enable transparent, reproducible and transdisciplinary research.[29]

Funders' mandates

Several funding bodies which mandate Open Access also mandate Open Data. A good expression of requirements (truncated in places) is given by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR):[30]

- to deposit bioinformatics, atomic and molecular coordinate data, experimental data into the appropriate public database immediately upon publication of research results.

- to retain original data sets for a minimum of five years after the grant. This applies to all data, whether published or not.

Other bodies active in promoting the deposition of data as well as fulltext include the Wellcome Trust. An academic paper published in 2013 advocated that Horizon 2020 (the science funding mechanism of the EU, due to launch in 2014) should mandate that funded projects hand in their databases as "deliverables" at the end of the project, so that they can be checked for third party usability then shared.[31]

Non-Open data

Several mechanisms restrict access to or reuse of data (and several reasons for doing this are given above). They include:

- making data available for a charge.

- compilation in databases or websites to which only registered members or customers can have access.

- use of a proprietary or closed technology or encryption which creates a barrier for access.

- copyright forbidding (or obfuscating) re-use of the data, including the use of "no derivatives" requirements.

- patent forbidding re-use of the data (for example the 3-dimensional coordinates of some experimental protein structures have been patented).

- restriction of robots to websites, with preference to certain search engines.

- aggregating factual data into "databases" which may be covered by "database rights" or "database directives" (e.g. Directive on the legal protection of databases).

- time-limited access to resources such as e-journals (which on traditional print were available to the purchaser indefinitely).

- "webstacles", or the provision of single data points as opposed to tabular queries or bulk downloads of data sets.

- political, commercial or legal pressure on the activity of organisations providing Open Data (for example the American Chemical Society lobbied the US Congress to limit funding to the National Institutes of Health for its Open PubChem data).[32]

Organisations promoting open data

- ArcGIS Open Data

- Bloomberg L.P. via Financial Instrument Global Identifier also see: Bloomberg Open Symbology

- Blue Obelisk

- Center for Government Excellence, Johns Hopkins University

- CiteSeer

- Common Crawl

- cTuning.org

- Datos Peru

- Data Republic

- Development Gateway

- Ecodesk

- ENGAGE platform

- Factual

- Freebase

- Free Our Data[33]

- GOPI: Geospatial Open Data Portal 4 India

- GEO: Group on Earth Observations

- Global Open Data in Agriculture and Nutrition- GODAN[34]

- Hack de Overheid

- Health Data Consortium

- Information Retrieval Facility

- Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), Georgia

- International Development Research Centre

- Junar

- Knoema

- LIBER

- LinkedScience.org[35]

- Newsjelly

- OMG standard

- Open & Agile Smart Cities (OASC)

- OpenCorporates

- OpenDataSoft

- The Open Data Innovation Gathering

- Open Data Institute

- Open Data Nottingham

- Opendata.ch

- Open Data Sri Lanka

- Open Energy Modelling Initiative

- The Open Institute

- Open Knowledge International (was Open Knowledge Foundation)

- Open Power System Data

- Open State Foundation

- Quandl

- Renewable Energy & Energy Efficiency Partnership

- Rijksmuseum Amsterdam[36]

- Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition

- Socrata

- Sunlight Foundation

- Talis

- ThinkData Works with the Namara Platform http://namara.io/#/

- University of Babylon

- w3.org[37]

- Wikidata

See also

- Budapest Open Access Initiative

- Creative Commons license

- Data curation

- Data governance

- Data management

- Demand responsive transport

- Digital preservation

- International Open Data Day

- Linked Data and Linked Open Data

- Merton Thesis

- Open energy system databases

- Urban informatics

References

- ↑ Auer, S. R.; Bizer, C.; Kobilarov, G.; Lehmann, J.; Cyganiak, R.; Ives, Z. (2007). "DBpedia: A Nucleus for a Web of Open Data". The Semantic Web. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 4825. p. 722. ISBN 978-3-540-76297-3. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-76298-0_52.

- ↑ See Open Definition home page and the full Open Definition

- ↑ Science Commons

- ↑ Connolly, Dan (16 November 2005). "Semantic Web Data Integration with hCalendar and GRDDL". W3C Talks and Presentations. XML Conference & Exposition 2005, Atlanta, Georgia, USA: W3C. p. 2. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ↑ Veen, Jeffrey (2 November 2005). "Polar Heart Rate Monitors: Gimme my data!". A website by Jeffrey Veen.

- ↑ Committee on Scientific Accomplishments of Earth Observations from Space, National Research Council (2008). Earth Observations from Space: The First 50 Years of Scientific Achievements. The National Academies Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-309-11095-5. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑ World Data Center System (18 September 2009). "About the World Data Center System". NOAA, National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ↑ Human Genome Project, 1996. Summary of Principles Agreed Upon at the First International Strategy Meeting on Human Genome Sequencing (Bermuda, 25–28 February 1996)

- ↑ Perkmann, Markus and Schildt, Henri, Open Data Partnerships between Firms and Universities: The Role of Boundary Organizations, Research Policy 44 (2015) 1133–1143

- ↑ OECD Declaration on Open Access to publicly funded data Archived 20 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding

- ↑ Dataverse Network Project

- ↑ Gray, Jonathan. "Towards a Genealogy of Open Data". SSRN Electronic Journal. Social Science Research Network (SSRN). doi:10.2139/ssrn.2605828.

- ↑ Brito, Jerry. "Hack, Mash, & Peer: Crowdsourcing Government Transparency". Colum. Sci. & Tech. L. Rev. 119 (2008).

- ↑ data.ca.gov

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ EU Open Data Portal

- ↑

- ↑ "The Open Data Charter: A Roadmap for Using a Global Resource". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ On the road to open data, by Ian Manocha

- ↑ "Big Data for Development: From Information- to Knowledge Societies", Martin Hilbert (2013), SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2205145. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2205145

- ↑ How to Make the Dream Come True argues in one research area (Astronomy) that access to open data increases the rate of scientific discovery.

- ↑ Khodiyar, Varsha. "Stopping the rot: ensuring continued access to scientific data, irrespective of age". F1000 Research. F1000. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- ↑ Magee, Andrew F.; May, Michael R.; Moore, Brian R.; Murphy, William J. (24 October 2014). "The Dawn of Open Access to Phylogenetic Data". PLoS ONE. 9 (10): e110268. PMC 4208793

. PMID 25343725. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110268.

. PMID 25343725. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110268. - ↑ Towards a Science Commons includes an overview of the basis of Openness in science data.

- ↑ Protocol for Implementing Open Access Data

- ↑ http://drexel-coas-elearning.blogspot.com/2006/09/open-notebook-science.html creation of term

- ↑ Kauppinen, T.; Espindola, G. M. D. (2011). "Linked Open Science-Communicating, Sharing and Evaluating Data, Methods and Results for Executable Papers". Procedia Computer Science. 4: 726. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2011.04.076.

- ↑ SPARC-OpenData@arl.org Mailing List Archive

- ↑ Galsworthy, M.J. & McKee, M. (2013). Europe's "Horizon 2020" science funding programme: How is it shaping up? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. doi: 10.1177/1355819613476017

- ↑ Review of history and positions by the University of California

- ↑ "Free our data" (The Guardian technology section)

- ↑ GODAN background

- ↑ http://linkedscience.org/about

- ↑ Open Cultuur Data, Rijksmuseum, 11 September 2012

- ↑ Linking Open Data on the Semantic Web

External links

- Open Data – An Introduction – from the Open Knowledge Foundation

- Video of Tim Berners-Lee at TED (conference) 2009 calling for "Raw Data Now"

- Six minute Video of Tim Berners-Lee at TED (conference) 2010 showing examples of open data

- G8 Open Data Charter

- Towards a Genealogy of Open Data – research paper tracing different historical threads contributing to current conceptions of open data.

- What is open data - an accessible summary of open data from the Open Data Institute

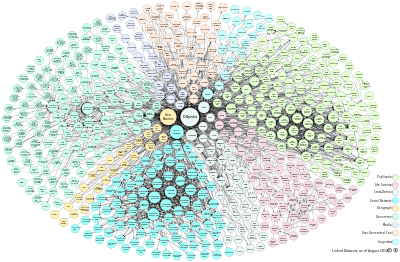

- Open Data Inception - 2600+ Open Data Portals Around the World