Opelousas, Louisiana

- Opelousas is also a common name of the flathead catfish.

| Opelousas, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

Old Federal Courthouse in Opelousas, listed on the National Register of Historic Places | |

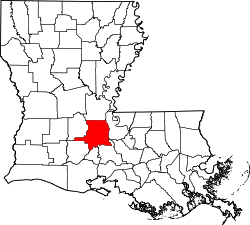

Location of Opelousas in St. Landry Parish, Louisiana. | |

.svg.png) Location of Louisiana in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 30°31′41″N 92°05′04″W / 30.52806°N 92.08444°WCoordinates: 30°31′41″N 92°05′04″W / 30.52806°N 92.08444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | St. Landry |

| Incorporated | 1720 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Reggie Tatum |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 7.93 sq mi (20.53 km2) |

| • Land | 7.93 sq mi (20.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 69 ft (21 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 16,634 |

| • Estimate (2016)[2] | 16,541 |

| • Density | 2,086.67/sq mi (805.63/km2) |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 70570 |

| Area code(s) | 337 |

| FIPS code | 22-58045 |

| Website | http://www.cityofopelousas.com |

Opelousas (French: les Opelousas) is a small city in and the parish seat of St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, United States.[3] It lies at the junction of Interstate 49 and U.S. Route 190. The population was 22,860 at the 2000 census. Although the 2006 population estimate was 23,222, a 2004 annexation should have put the city's population above 25,000. In the 2010 census, however, the population shrunk to 16,634.[4] Opelousas is the principal city for the Opelousas-Eunice Micropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated population of 92,178 in 2008. Opelousas is also the third largest city in the Lafayette-Acadiana Combined Statistical Area, which has a population of 537,947.

At 7.5 square miles, Opelousas is the most densely populated incorporated city in Louisiana. Founded in 1720, Opelousas is Louisiana's third oldest city. The city served as a major trading post between New Orleans and Natchitoches in the 18th and 19th centuries. Traditionally an area of settlement by French Creoles and Acadians, Opelousas is the center of zydeco music. It celebrates its heritage at the Creole Heritage Folklife Center, one of the destinations on the new Louisiana African American Heritage Trail. It is also the location of the Evangeline Downs Racetrack and Casino.

The city calls itself the spice capital of the world, with production and sale of seasonings such as Tony Chachere's products,[5] Targil Seasonings,[6] Savoie's cajun meats and products,[7] and LouAna Cooking Oil. Opelousas was also home to one of the nation's two Yoohoo Factories until their closing.

During the tenure of Sheriff Cat Doucet from 1936 to 1940 and 1952 to 1968 that part of Opelousas along Highway 190 was a haven of gambling and prostitution. Doucet told historian Michael Kurtz that the return of Earl Long to the governorship in 1956 allowed him to bring back brothels and casinos and to guarantee the sheriff a take of the proceeds.[8]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 786 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,546 | 96.7% | |

| 1880 | 1,676 | 8.4% | |

| 1890 | 1,572 | −6.2% | |

| 1900 | 2,951 | 87.7% | |

| 1910 | 4,623 | 56.7% | |

| 1920 | 4,437 | −4.0% | |

| 1930 | 6,299 | 42.0% | |

| 1940 | 8,980 | 42.6% | |

| 1950 | 11,659 | 29.8% | |

| 1960 | 17,417 | 49.4% | |

| 1970 | 20,387 | 17.1% | |

| 1980 | 18,903 | −7.3% | |

| 1990 | 18,151 | −4.0% | |

| 2000 | 22,860 | 25.9% | |

| 2010 | 16,634 | −27.2% | |

| Est. 2016 | 16,541 | [2] | −0.6% |

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 16,634 people residing in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 74.8% Black, 21.9% White, 0.3% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.2% from some other race and 1.0% from two or more races. 1.2% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[10] of 2000, there were 22,860 people, 8,699 households, and 5,663 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,240.0 people per square mile (1,250.2/km²). There were 9,783 housing units at an average density of 1,386.6 per square mile (535.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 69.12% African American, 29.30% White, 0.10% Native American, 0.32% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.30% from other races, and 0.84% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.88% of the population. In 2000, 89.1% of the population over the age of five spoke English at home, 9.7% of the population spoke French or Cajun, and 0.7% spoke Louisiana Creole French.[11]

There were 8,699 households out of which 32.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.7% were married couples living together, 26.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.9% were non-families. 32.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.24.

In the city, the population was spread out with 30.3% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 24.9% from 25 to 44, 19.6% from 45 to 64, and 15.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 84.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $14,717, and the median income for a family was $19,966. Males had a median income of $24,588 versus $17,104 for females. The per capita income for the city was $9,957. About 37.7% of families and 43.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 57.2% of those under age 18 and 32.0% of those age 65 or over.

History

Early years

Opelousas takes its name from the Native American tribe Appalousa who had occupied the area before European contact.

The first recorded European arrived in the Appalousa Territory in 1690. He was a French coureur de bois (trapper and hunter). French traders arrived later to trade with the Appalousa Indians. In 1719, the French sent the first military to the Territory, when Ensign Nicolas Chauvin de la Frénière and two others were sent to patrol the area and in 1720, the French established Opelousas Post as a major trading organization for the developing area. The French encouraged immigration to Opelousas Post before they ceded Louisiana to Spain in 1762. By 1769 about 100 families, mostly French, were living in the Post. In 1767 Saint Landry Catholic Church was built. Don Alejandro O'Reilly, Spanish governor of Louisiana, issued a land ordinance to allow settlers in the frontier of the Opelousas Territory to acquire land grants. The first official land grant was made in 1782. Numerous settlers: French, Creoles and Acadians, mainly from the Attakapas Territory, came to the Opelousas Territory and acquired land grants.

After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, settlers continued to arrive from St. Martinville. LeBon, Prejean, Thibodaux, Esprit, Nezat, Hebert, Babineaux, Mouton, and Provost were some of the early Creole families. (This was Creole as French born in Louisiana, see Louisiana Creole people.) Other early French Creole families were Roy, Barre, Guenard, Decuir, and Bail. In 1820, Alex Charles Barre, also a French Creole, founded Port Barre. His ancestors came from the French West Indies, probably after Haiti (St. Domingue) became independent. Jim Bowie and his family were said to have settled in the area circa 1813. In 1805, Opelousas became the seat of the newly formed St. Landry Parish, also known as the Imperial Parish of Louisiana. The year 1806 marked the beginning of significant construction in Opelousas. The first courthouse was constructed in the middle of the town. Later in 1806, Louisiana Memorial United Methodist Church was founded, becoming the first Methodist, as well as Protestant, church in Louisiana. Five years later, the first St. Landry Parish Police Jury met in Opelousas, keeping minutes in the two official languages of English and French. The city was incorporated in 1821.

American Civil War

European and American settlement was based on plantation agriculture, and both groups brought or purchased numerous enslaved Africans and African Americans to work as laborers in cotton cultivation. African Americans influenced all cultures as the people created a creolized cuisine and music. The long decline of cotton prices throughout the 19th century created economic problems worsened by the lack of employment diversity.

In 1862, after Baton Rouge fell to the Union troops during the Civil War, Opelousas was designated the state capital for nine months. The governor's mansion in Opelousas, which was the oldest remaining governor's mansion in Louisiana, was the victim of arson on July 14, 2016, and the structure was reduced to a chimney and its foundation. The one story mansion was located on the corner of Liberty and Grolee Streets, just west of the heart of town. An observation tower was removed from the top of the residence in the early 1900s but the remainder of the exterior was identical to its original construction in the 1850s. The entire roof section of heavy rafters was held in place by thousands of wooden pegs, not one nail could be found in the attic. There were plans to restore the building to some of its former splendor.[12] The capitol was moved again in 1863, this time to Shreveport, when Union troops occupied Opelousas. During Reconstruction, the state government operated from New Orleans.

The Union forces led by General Nathaniel P. Banks who occupied Opelousas found what the historian John D. Winters describes as "a beautiful town boasting several churches, a fine convent, and a large courthouse," far superior in appearance to nearby Washington, also in St. Landry Parish.[13] Early in 1864, jayhawkers began to make daring daytime raids in parts of St. Landry Parish near Opelousas. According to Winters in his The Civil War in Louisiana, the thieves "robbed the inhabitants in many instances of everything of value they possessed, but taking particularly all the fine horses and good arms they could find."[14] Winters added that conscription in the area came to a standstill, as men could avoid the army by staying within the lines of the jayhawkers. The conscripts who did not join the lawless element stayed home until the state or the army could protect their families."[14]

Reconstruction

After the defeat of the South and emancipation of slaves, many whites had difficulty accepting the changed conditions, especially as economic problems and dependence on agriculture slowed the South's recovery. Social tensions were high during Reconstruction. In 1868, a white mob rioted and killed 25-50 freedmen in Opelousas. Some reports put the number killed even higher, ranging from 200-300, and it was one of the single worst instances of Reconstruction violence in south Louisiana. Opelousas enacted ordinances following the abolition of slavery that served to greatly restrict the freedoms of black Americans. These codes[15][16] required blacks to have a written pass from their employer to enter the town and to state the duration of their visit. Blacks were not allowed on the streets after 10 p.m, they could neither own a house nor reside in the town, unless the employee of a white person, and they were also not allowed in the town after 3 p.m. on Sundays.[17]

Home of refugees

In 1880, the railroad reached Opelousas. In the late 19th century, New York City social services agencies arranged for resettlement of Catholic orphan children by sending them to western rural areas, including Opelousas, in Louisiana and other states. At least three Orphan Trains reached this city before 1929. Opelousas is the heart of a traditional Catholic region of French, Spanish, Canadian and French West Indian ancestry. Catholic families in Louisiana took in more than 2,000 mostly Catholic orphans to live in their rural farming communities.[18]

In May 1927, Opelousas accepted thousands of refugees following the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 in the Mississippi Delta. Heavy rains in northern and midwestern areas caused intense flooding in areas of Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana downstream, especially after levées near Moreauville, Cecilia and Melville collapsed. More than 81 percent of St. Landry Parish suffered some flooding, with 77 percent of the inhabitants directly affected. People in more southern areas of Louisiana, especially those communities along Bayou Teche, were forced to flee their homes for areas that suffered less damage. By May 20, over 5,700 refugees were registered in Opelousas, which population at the time was only 6,000 people. Many of the refugees later returned to their homes and begin the rebuilding process.[19]

Festivals

The Yambilee Festival began in 1946 and is the oldest festival held each year in Opelousas. It starts on the Wednesday before the last full weekend of October and continues throughout the weekend with events including concerts, cooking competitions, a parade and beauty pageants.

Since 1982, Opelousas has hosted the Original Southwest Louisiana Zydeco Festival.[20] Usually held the Saturday before Labor Day at Zydeco Park in Plaisance, the festival features a day of performances by Zydeco musicians, with the goal of keeping the genre alive.[21]

Additional annual events include:

- Frank's Downtown Gumbo Cook-off - January

- Zydeco Extravaganza - May

- Juneteenth Festival- 3rd Saturday every June, celebration of end of the Civil War and emancipation of slaves

- Holy Ghost Creole Festival[22] - 1st weekend of November, near All Saints Day (Nov.1)

- Christmas Lighting of Le Vieux Village- 1st Friday every December

- Frank's Mardi Gras Parade- Mardi Gras (Tuesday before Ash Wednesday in French Catholic tradition)

- Opelousas Mardi Gras Celebration/Street Dance on Court St.- Mardi Gras

Education

Opelousas is home to several public and private schools. The private schools include Opelousas Catholic School, Westminster Christian Academy,[23] Apostolic Christian Academy, New Hope Christian Academy, and Family Worship Christian Academy (FWCA). Opelousas has many public high schools, which are Opelousas Senior High, Northwest High School, and MACA. Opelousas Junior High serves as the area middle school. The city has seven public elementary schools and is home to one of the campuses of South Louisiana Community College.

Media

Opelousas is part of the Lafayette television and radio markets.

Opelousas is home to KOCZ-LP, a low power community radio station owned and operated by the Southern Development Foundation. The station was built by numerous volunteers from Opelousas and around the country at the third Prometheus Radio Project barnraising.

KOCZ broadcasts music, news, and public affairs to listeners now at 92.9, originally was on 103.7, but had to move due to a full power station being licensed to 103.7.[24] Opelousas is home to The Mix KOGM 107.1FM which is owned by KSLO Broadcasting, Inc. There are 2 TV stations based in Opelousas, KDCG-CD (Class A Digital) TV Channel 22 and K39JV, another low power on channel 39.

Economy

The primary industries in Opelousas are agriculture, oil, manufacturing, wholesale, and retail.

In September 1999, Wal-Mart opened a large distribution center just north of the city. It is currently generating an $89 million impact per year to the area, employing over 600 full-time workers.

Horse racing track Evangeline Downs relocated to Opelousas from its former home in Carencro, Louisiana in 2003 and employs over 750 workers.

Notable people

- Daniel Baldridge, Offensive tackle for the Jacksonville Jaguars and the Tennessee Titans.

- Jim Bowie, legendary adventurer and hero of the Alamo, lived in Opelousas for a time.

- Tex Brashear, voice-over/cartoon voice actor.

- Carl Brasseaux, historian of French Colonial Louisiana.

- Chef Tony Chachere was born in Opelousas, site of Tony Chachere Creole Foods, which is still in operation

- Clifton Chenier, legendary zydeco musician

- Cindy Courville, first US Ambassador to the African Union

- Jay Dean, mayor of Longview, Texas, 2005-2015; Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives, effective 2017; born in Opelousas in 1953

- Cat Doucet, Sheriff of St. Landry Parish, 1936–40; 1952–68

- W.W. Dumas, Mayor-President of East Baton Rouge Parish from 1965–80, was born in Opelousas in 1916

- Bobby Dunbar, noted kidnap victim

- Gilbert L. Dupré, state representative and district court judge for St. Landry Parish

- H. Garland Dupré, state representative and U.S. representative for Louisiana's 2nd congressional district in New Orleans, born in Opelousas in 1873

- Sue Eakin (1918–2009), based in Bunkie, was a columnist for the Opelousas Daily World and several other newspapers

- Richard Eastham (1916–2005), an American actor, was born in Opelousas. He played Harris Claibourne, a newspaper editor in the 1957-1960 ABC and later syndicated western series, Tombstone Territory. He also appeared in Disney's Toby Tyler and That Darn Cat!.

- E. D. Estilette (1833-1919), state court judge and member of the Louisiana House of Representatives; House Speaker in 1876, resided and buried in Opelousas

- Antoinette Frank, death row inmate at the Louisiana Correctional Institute.[25]

- W. C. Friley, Baptist clergyman; through a series of revival meetings in 1880 helped to establish First Baptist Church Opelousas

- T. H. Harris, state education superintendent from 1908 to 1940, was principal of St. Landry High School in Opelousas prior to 1900; Louisiana Technical College's T. H. Harris Campus named in his honor

- Devery Henderson, New Orleans Saints wide receiver

- Ivan L. R. Lemelle, Federal Judge, U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana, nominated by President Clinton; former U.S. Magistrate Judge of the same district

- Rod Milburn, 1972 Summer Olympics champion

- Brigadier General J.J. Alfred Mouton, CSA. Born in Opelousas on February 29, 1829, he was a Confederate General under General Richard Taylor, and was killed during the Battle of Mansfield, Louisiana

- Lloyd Mumphord, standout NFL cornerback and special teams captain of the legendary perfect season Miami Dolphins (1972–73); two-time Super Bowl champion

- Benjamin Pavy, judge and jurist; father-in-law of Carl Weiss, declared assassin of Huey Long

- Felix Octave Pavy, M.D., member of the Louisiana House of Representatives for St. Landry Parish from 1932 to 1936[26]

- Vincent Pierre, state representative for Lafayette Parish since 2012; former Opelousas resident[27]

- Paul Prudhomme, chef

- Georgia Ann Robinson, Los Angeles Police Department officer

- Mabel Sonnier Savoie, American singer, guitarist

- Krista Stegall, contestant on American reality show Big Brother 2

- Louisiana Chief Justice Albert Tate, Jr., who later served on the United States Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, based in New Orleans.

- Ledricka Thierry, state representative for St. Landry Parish from 2009 to 2016

- Marvin White, Cincinnati Bengals' safety

- J. Robert Wooley, Louisiana insurance commissioner from 2000–06; practiced law in Opelousas as a young attorney in the late 1970s.

Miscellany

Musician Billy Cobham recorded a song called "Opelousas" on his 1978 album Simplicity of Expression - Depth of Thought (Columbia Records JC 35457).

1980s synthpop musician Thomas Dolby speaks of Opelousas in the first person in the song I Love You Goodbye from his 1992 album Astronauts & Heretics. The folk-rock singer Lucinda Williams mentions Opelousas in the song Concrete and Barbed Wire from her critically acclaimed album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road. Singer-songwriter and comedian Henry Phillips mentions Opelousas as one of the venues in his song I'm In Minneapolis (You're In Hollywood).

References

- ↑ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 2, 2017.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml

- ↑ cajunspice.com

- ↑ "targil.com". targil.com. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ "savoiefoods.com". Savoiesfoods.com. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ "Stanley Nelson, Matt Barnidge, and Ian Stanford, "Connected by violence: the mafia, the Klan & Morville Lounge"". Concordia Sentinel, July 16, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ http://www.mla.org/cgi-shl/docstudio/docs.pl?map_data_results

- ↑ Former governor's mansion undergoing improvements", dailyworld.com; accessed March 17, 2014.

- ↑ John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963; ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 233

- 1 2 Winters, p. 322

- ↑ Encyclopedia.com Like the Black Codes, police regulations restricted the freedoms and personal autonomy of freedmen after the Civil War in the South.

- ↑ The Opelousas, Courier Opelousas, La., 1852-1910, April 20, 1872 Proceedings Of the Board of Police of the Town of Opelousas, on Monday, April 8th. 1872., H. LATOUR, President, Attest: P. LEONCE HEBRARD, Clerk of the Board

- ↑ Black Reconstruction (NY: Harcourt Brace, 1935). W.E.B. Du Bois

- ↑ "St. Landry Parish profile". Cajuntravel.com. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ↑ Speyrer, John A. "1927 High Water in St. Landry Parish". Speyrer Family Association Newsletter. Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ↑ "zydeco.org". zydeco.org. 2013-08-31. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ "Opelousas Festivals". City of Opelousas. Archived from the original on 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ "holyghostcreolefestival.com". holyghostcreolefestival.com. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ "Westminster Christian Academy website". wcala.org. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ KOCZ licensing information, licensing.fcc.gov; accessed June 24, 2014.

- ↑ Filosa, Gwen (April 22, 2008). "Orleans Judge Sets July 15 Execution Date for Antoinette Frank". The Times-Picayune.

- ↑ "Felix Octave Pavy". New Orleans Times-Picayune. May 14, 1962. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Vincent J. Pierre". intelius.com. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

Further reading

- Andrepont, Carola Ann (1992). Opelousas, A Great Place to Be!. Opelousas.: Andrepont Printing. OCLC 26884714.

- Brasseaux, Carl A. (1996). Creoles of Color in the Bayou Country. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. OCLC 45733128.

- Brasseaux, Carl A. (1987). The Founding of New Acadia: The Beginnings of Acadian Life in Louisiana, 1765-1803. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 45843681.

- De Ville, Winston (1973). Opelousas: The History of a French and Spanish Military Post in America, 1716-1803. Cottonport, Louisiana: Polyanthos. OCLC 724500.

- Fontenot, Ruth Robertson (1955). Some History of St. Landry Parish from the 1690s. Opelousas: (The Opelousas) Daily World. OCLC 5581766.

- Harper, John N. (1993). Mother Church of Acadiana: The History of the St. Landry Catholic Church in Opelousas, Louisiana. Rayne, Louisiana: Hebert Publications. OCLC 28717087.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Opelousas, Louisiana. |

- Official website

- Opelousas and St. Landry Parish

- Louisiana's African American Heritage Trail

- St. Landry Parish Economic Industrial Development District

- St. Landry Parish Tourist Commission

- USGenWeb St. Landry Parish

- USGenWeb Genealogy Records for St. Landry Parish