Opaque forest problem

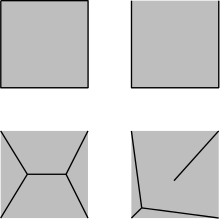

In computational geometry, The opaque forest problem can be stated as follows: "Given a convex polygon C in the plane, determine the minimal forest T of closed, bounded line segments such that every line through C also intersects T". T is said to be the opaque forest, or barrier of C. C is said to be the coverage of T. While any forest that covers C is a barrier of C, we wish to find the one with shortest length.

It may be the case that T is constrained to be strictly interior or exterior to C. In this case, we specifically refer to a barrier as interior or exterior. Otherwise, the barrier is assumed to have no constraints on its location.

History and difficulty

The opaque forest problem was originally introduced by Mazurkiewicz in 1916.[1] Since then, not much progress has been made with respect to the original problem. There does not exist any verified general solution to the problem. In fact, the optimal solution for even simple fixed inputs such as the unit square or equilateral triangle are unknown. There exist conjectured optimal solutions to both of these instances, but we currently lack the tooling to prove that they are optimal.[2] While general solutions to the problem have been claimed by several individuals,[3][4] they either haven't been peer reviewed or have been demonstrated to be incorrect.[5][6]

Bounding the optimal solution

Given a convex polygon C with perimeter p it is possible to bound the value of the optimal solution in terms of p. These bounds are individually tight in general, but due to the various shapes that can be provided, are quite loose with respect to each other.

In general, one can prove that p/2 ≤ |OPT| ≤ p.

Upper bound

It is not hard to convince oneself that simply tracing out the perimeter of C is always sufficient to cover it. Therefore p is an upper bound for any C. For internal barriers, this bound is tight in the limiting case of when C is a circle; every point q on the perimeter of the circle must be contained in T, or else a tangent of C can be drawn through q without intersecting T. However for any other convex polygon, this is suboptimal, meaning that this is not a particularly good upper bound for most inputs.

For most inputs, a slightly better upper bound for convex polygons can be found in the length of the perimeter, less the longest edge (which is the minimum spanning tree). Even better, one can take the minimum Steiner tree of the vertices of the polygon. For internal barriers, the only way to improve this bound is to make a disconnected barrier.

Lower bound

Various proofs of the lower bound can be found in .[7] To see that this is tight in general, one can consider the case of a stretching out a very long and thin rectangle. Any opaque forest for this shape must be at least as long as the rectangle, or else there is a hole through which vertical lines can pass through. As the rectangle becomes longer and thinner, this value approaches p/2. Therefore this bound is tight in general. However for any shape that actually has a positive area, some extra length will need to be allocated to span the shape in other directions. Hence this is not a particularly good lower bound for most inputs.

Special cases

For the unit square, these bounds evaluate to 2 and 4 respectively. However, slightly improved lower bounds of 2 + 10−12 for barriers that satisfy a locality constraint, and 2 + 10−5 for internal barriers, have been claimed.[8] However, the proof of this has not yet been peer reviewed.

Approximations

Due to the difficulty faced in finding an optimal barrier for even simple examples, it has become very desirable to find a barrier that approximates the optimal within some constant factor.

Dumitrescu et al.[9] provide several linear-time approximations for the optimal solution. For general barriers, they provide a 1/2 + (2 + √2)/π = 1.5867... approximation ratio. For connected barriers, they improve this ratio to 1.5716. If the barrier is constrained to a single arc, they achieve a (π + 5)/(π + 2) = 1.5834 approximation ratio.

Barrier verification and computing the coverage of forests

Most barrier constructions are such that the fact that it covers the desired region is guaranteed. However, given an arbitrary barrier T, it would be desirable to confirm that it covers the desired area C.

As a simple first pass, one can compare the convex hulls of C and T. T covers at most its convex hull, so if the convex hull of T does not strictly contain C, then it cannot possibly cover T. This provides a simple O(n log n) first-pass algorithm for verifying a barrier. If T consists of a single connected component, then it covers exactly its convex hull, and this algorithm is sufficient. However, If T contains more than one connected component, it may cover less. So this test is not sufficient in general.

The problem of determining exactly what regions any given forest T consisting of m connected components and n line segments actually covers, can be solved in Θ(m2n2) time.[10] The basic procedure for doing this is simple: first, simplify each connected component by replacing it with its own convex hull. Then, for vertex p of each convex hull, perform a circular plane-sweep with a line centered at p, tracking when the line is or isn't piercing a convex hull (not including the point p itself). The orientations of the sweep-line during which an intersection occurred produce a "sun" shaped set of points (a collection of double-wedges centred at p). The coverage of T is exactly the intersection of all of these "suns" for all choices of p.

While this algorithm is worst-case optimal, it often does a lot of useless work when it doesn't need to. In particular, when the convex hulls are first computed, many of them may overlap. If they do, they can be replaced by their combined convex hull without loss of generality. If after merging all overlapping hulls, a single barrier has resulted, then the more general algorithm need not be run; the coverage of a barrier is at most its convex hull, and we have just determined that its coverage is its convex hull. The merged hulls can be computed in O(nlog2n) time. Should more than one hull remain, the original algorithm can be run on the new simplified set of hulls, for a reduced running time.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ S. Mazurkiewicz, Sur un ensemble ferm´e, punctiforme, qui rencontre toute droite passant par un certain domaine (Polish, French summary), Prace Mat.-Fiz. 27 (1916), 11–16.

- ↑ Opaque sets; Approximation, Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques; 194–205

- ↑ V. Akman, An algorithm for determining an opaque minimal forest of a convex polygon, Information Processing Letters, 24 (1987), 193–198.

- ↑ P. Dublish, An O(n3) algorithm for finding the minimal opaque forest of a convex polygon, Information Processing Letters, 29(5) (1988), 275–276.

- ↑ T. Shermer, A counterexample to the algorithms for determining opaque minimal forests, Information Processing Letters, 40 (1991), 41–42.

- ↑ J. S. Provan, M. Brazil, D. A. Thomas and J. F. Weng, Minimum opaque covers for polygonal regions, manuscript, October 2012, arXiv:1210.8139v1

- ↑ A, Dumitrescu and M. Jiang, The Opaque Square (2013) http://arxiv.org/pdf/1311.3323v1.pdf

- ↑ A. Dumitrescu and M. Jiang, The Opaque Square (2013) http://arxiv.org/pdf/1311.3323v1.pdf

- ↑ A. Dumitrescu, M. Jiang, and J. Pach. Opaque sets. Algorithmica. To appear. Online first, December 2012.

- ↑ A. Beingessner, M. Smid, Computing the Coverage of an Opaque Forest, 24th Annual Canadian Conference on Computation Geometry (2012)

- ↑ Luis Barba, Alexis Beingessner, Prosenjit Bose, Michiel H. M. Smid: Computing Covers of Plane Forests. 25th Annual Canadian Conference on Computational Geometry (2013)