Omagh

| Omagh | |

|---|---|

Omagh Coat of Arms | |

Omagh | |

| Omagh shown within Northern Ireland | |

| Population | 21,297 [3] |

| District | |

| County | |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | OMAGH |

| Postcode district | BT78, BT79 |

| Dialling code | 028 |

| Police | Northern Ireland |

| Fire | Northern Ireland |

| Ambulance | Northern Ireland |

| EU Parliament | Northern Ireland |

| UK Parliament | |

| NI Assembly | |

| Website | Official website |

Omagh (/ˈoʊmə/[4] or /ˈoʊmɑː/; from Irish: An Ómaigh, meaning "the virgin plain" [ənˠˈ-oː-mˠ-əi-])[5] is the county town of County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is situated where the rivers Drumragh and Camowen meet to form the Strule. Northern Ireland's capital city Belfast is 68 miles (109.5 km) to the east of Omagh, and Derry is 34 miles (55 km) to the north.

The town has a population of 21,297,[3] and the former district council, which was the largest in County Tyrone, had a population of 51,356 at the 2011 Census. Omagh contains the headquarters of the Western Education and Library Board, and also houses offices for the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development at Sperrin House, the Department for Regional Development and the Northern Ireland Roads Service at the Tyrone County Hall and the Northern Ireland Land & Property Services at Boaz House. The town is twinned with L'Haÿ-les-Roses, a town in the suburbs of Paris, France.

History

The name Omagh is an anglicisation of the Irish name an Óghmaigh (modern Irish an Ómaigh), meaning "the virgin plain". A monastery was apparently established on the site of the town about 792, and a Franciscan friary was founded in 1464.[6] Omagh was founded as a town in 1610. It served as a refuge for fugitives from the east of County Tyrone during the 1641 Rebellion. In 1689, James II arrived at Omagh, en route to Derry. Supporters of William III, Prince of Orange, later burned the town.

In 1768 Omagh replaced Dungannon as the county town of County Tyrone. Omagh acquired railway links to Londonderry with the Londonderry and Enniskillen Railway in 1852, Enniskillen in 1853 and Belfast in 1861. St Lucia Barracks were completed in 1881. In 1899 Tyrone County Hospital was opened. Today the hospital is the subject of a major campaign to save its services. The Government of Northern Ireland made the Great Northern Railway Board close the Omagh – Enniskillen railway line in 1957.[7] In accordance with the Benson Report submitted to the Northern Ireland Government in 1963, the Ulster Transport Authority closed the Portadown – Omagh – Londonderry main line in 1965,[8] leaving Tyrone with no rail service. St Lucia Barracks closed on 1 August 2007.[9]

The Troubles

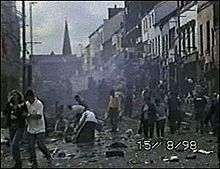

Omagh came into the international focus of the media on 15 August 1998, when the Real Irish Republican Army exploded a car bomb in the town centre. 29 people were killed in the blast – 14 women (including one pregnant with twins), 9 children and 6 men. Hundreds more were injured as a result of the blast.

In April 2011, a car bomb killed police constable Ronan Kerr. A group of former Provisional IRA members calling itself the Irish Republican Army made its first public statement later that month claiming responsibility for the killing.[10]

Geography

Wards

These wards are only those that cover the town.

- Camowen (2001 Population – 2,377)

- Coolnagard (2001 Population – 2,547)

- Dergmoney (2001 Population – 1,930)

- Drumragh (2001 Population – 2,481)

- Gortrush (2001 Population – 2,786)

- Killyclogher (2001 Population – 2,945)

- Lisanelly (2001 Population – 2,973)

- Strule (2001 Population – 1,780)

Townlands

%2C_Omagh_-_geograph.org.uk_-_754131.jpg)

The town sprang up within the townland of Omagh, in the parish of Drumragh. Over time, the urban area has spread into the surrounding townlands. They include:[11]

- Campsie

- Conywarren

- Coolnagard Lower, Coolnagard Upper (from Irish Cúil na gCeard, meaning 'nook/corner of the craftsmen' or from Irish Cúl na gCeard, meaning 'hill-back of the craftsmen')[12]

- Crevenagh

- Culmore (from Irish Cúil Mhór, meaning 'big nook/corner')[13]

- Dergmoney Lower, Dergmoney Upper (from Irish Deargmhuine, meaning 'red thicket')[14]

- Gortin

- Gortmore (from Irish Gort Mór, meaning 'big enclosed field')[15]

- Killybrack (from Irish Coillidh Bhreac, meaning 'speckled wood')[16]

- Killyclogher (from Irish Coillidh Chlochair, meaning 'wood of the stony place')[17]

- Lammy (from Irish Leamhaigh, meaning 'place of elms')[18]

- Lisanelly (from Irish Lios an Ailigh, meaning 'ringfort of the stony place')[19]

- Lisnamallard (from Irish Lios na Mallacht, meaning 'ringfort of the curse')[20]

- Lissan (from Irish Liosán, meaning 'small ringfort')[21]

- Mullaghmore (from Irish Mullach Mór, meaning 'big hilltop')[22]

- Sedennan (possibly from Irish Sidh Dianáin, meaning 'Dennan's fairy mound')[23]

- Strathroy (from Irish Srath Rua, meaning 'the red strath' or from Irish Srath Crua, meaning 'hard strath')[24]

Weather

.jpg)

An air temperature of −19.4 °C (−2.9 °F) was recorded once, and it remains the coldest air temperature ever recorded in Ireland.[25] Omagh has a history of flooding and suffered major floods in 1909, 1929, 1954, 1969, 1987, 1999 and, most recently, 12 June 2007. As a result of this, flood-walls were built to keep the water in the channel (River Strule) and to prevent it from overflowing into the flood plain. Large areas of land, mainly around the meanders, are unsuitable for development and were developed into large, green open areas, walking routes and parks. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb" (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[26]

| Climate data for Omagh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

19 (66) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

8 (46) |

13 (55) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

3 (37) |

3 (37) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 119 (4.7) |

79 (3.1) |

79 (3.1) |

74 (2.9) |

71 (2.8) |

69 (2.7) |

80 (3) |

64 (2.5) |

86 (3.4) |

122 (4.8) |

99 (3.9) |

117 (4.6) |

1,052 (41.4) |

| Source: Weatherbase [27] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Omagh is classified as a large town settlement by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA).[28] On Census day (27 March 2011) there were 19,659 people living in Omagh. Of these:

- 20.8% were aged under 16 years and 18.8% were aged 60 and over, with an average age of 34.0 years.

- 71.3% were from a Catholic background and 25.4% were from a Protestant background.

- 37.0% described their national identity as "Irish", 34.0% described their national identity as "Northern Irish" and 28.5% described their national identity as "British".

- 5.3% of people aged 16–74 were unemployed.

- 14.3% of people were born outside Northern Ireland.

Population change

According to the World Gazetter, the following reflects the census data for Omagh since 1981:[29]

- 1981 – 14,627 (Official census)

- 1991 – 17,280 (Official census)

- 2000 – 18,031 (Official estimate)

- 2001 – 19,910 (Official census)

- 2011 – 19,659 (Official census)

Places of interest

Tourist attractions

- The Ulster American Folk Park near Omagh includes the cottage where Thomas Mellon was born in 1813, before emigrating to Pennsylvania, in the United States when he was five. His son Andrew W. Mellon became secretary of the US Treasury. The park is an open-air museum that explores the journey made by the Irish (specifically those from Ulster) to America during the 1800s. The park is famous for its large events during Easter, Christmas, Fourth of July and Halloween. It also hosts a major Bluegrass festival every year. Over 127,000 people visited the park in 2003.[30]

- The Gortin Glens Forest Park, 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) north of Omagh is a large forest with many attractions, including a deer enclosure and many areas of natural beauty, including waterfalls, lakes, etc.

- Strule Arts Centre opened in 2007 is good example of urban renewal in Omagh town centre. Creating a modern civic building, in a newly created public space reclaimed from the formerly disused area, between the River Strule and High Street.

Parks

- Omagh boasts over 20 playgrounds for children,[31] and a large amount of green open area for all the public. The largest of these is the Grange Park, located near the town centre. Many areas around the meanders of the River Strule have also been developed into open areas. Omagh Leisure Complex is a large public amenity, near the Grange Park and is set in 11 hectares (27 acres) of landscaped grounds and features a leisure centre, boating pond, astroturf pitch and cycle paths.

Retail

Omagh is the main retail centre for Tyrone, as well as the West of Ulster (behind Derry and Letterkenny), due to its central location. In the period 2000–2003, over £80 million was invested in Omagh, and 60,960 m2 (656,200 sq ft) of new retail space was created. Shopping areas in Omagh include the Main Street Mall, Great Northern Road Retail Park and the Showgrounds Retail Park on Sedan Avenue in the town centre. Market Street/High Street is also a prominent shopping street, which includes popular high street stores such as DV8 and Primark.

Transport

Former railways

Neither the town nor the district of Omagh has any railway service.

The Irish gauge 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) Londonderry and Enniskillen Railway (L&ER) opened as far as Omagh on 3 September 1852[32] and was extended to Enniskillen in 1854.[33] The Portadown, Dungannon and Omagh Junction Railway (PD&O) reached Omagh in 1861,[33] completing the Portadown – Derry route that came to be informally called "The Derry Road".[34] The Great Northern Railway (Ireland) absorbed the PD&O in 1876[35] and the L&ER in 1883.[35]

The Government of Northern Ireland made the GNR Board close the Omagh – Enniskillen line in 1957.[7] The Ulster Transport Authority took over the GNR's remaining lines in Northern Ireland in 1958. In accordance with The Benson Report submitted to the Northern Ireland Government in 1963, the UTA closed the "Derry Road" through Omagh on 15 February 1965.[32][36][37] Later the Omagh Throughpass road was built on the disused trackbed though Omagh railway station.

Bus Services

Bus Services in Omagh are operated by Ulsterbus. The town has seven bus corridors that run daily which are the following:

384A- Strathroy

384B- Killyclogher

384C- Tamlaght Road

384D- Culmore Park and O'Kane Park

384E- Tyrone and Fermanagh Hospital

384F- Mullaghmore and Lisanelly Heights

384G- Dergmoney and Coolnagard Estate

Proposed railways

There is a proposal for Omagh to become a rail hub again by 2050. This is a proposal to reopen the rail line to Belfast via Portadown and also a rail link between Derry and Limerick via Omagh. However, this is only a proposal in the planning stage, and no plan has been finalised as yet.

A proposal to reopen the line between Portadown and Omagh was considered by the NI Department for Regional Development in their Future Railway Investment: A Consultation Paper in early 2013. The proposal is not ranked as a high priority in the report for railway investment from 2015 to 2035. The report estimates that a link from Portadown to Omagh would cost around £475 million, thought it admits that no detailed feasibility study has been carried out.

There are plans to reopen railway lines in Northern Ireland including the line from Portadown via Dungannon to Omagh.[38]

Road connections

- A32 (Omagh – Enniskillen – Ballinamore) (Becomes N87 at border)

- A5 (Northbound) (Omagh – Strabane [and from here north-west to Letterkenny, via Lifford on the A38, becoming the N14 at the county border] – Derry)

- A5 (Southbound) (Omagh – Monaghan – Ashbourne – Dublin) (Becomes N2 at border)

- A4 (Eastbound) (Omagh – Dungannon – Belfast) (A4 joins A5 near Ballygawley)

- A505 (Eastbound) (Omagh – Cookstown)

- The Omagh Throughpass (Stage 3) opened on 18 August 2006.

Major developments

Lisanelly Shared Educational Campus

The Department for Education proposed a plan to build Omagh's six existing secondary schools at the former 190-acre St Lucia Army Barracks, to form one large educational campus, with shared facilities, but with separate school buildings to enable each school to maintain their individual ethos'.

On 22 April 2009 at the inaugural Lisanelly Shared Educational Campus Steering Group meeting held in Arvalee School and Resource Centre, the Education Minister, Caitríona Ruane announced that funding had been allocated by the Department of Education and Strategic Investment Board Ltd to be used to develop exemplar designs and associated technical work for a Shared Educational Campus in Omagh.[39]

Work on the development began in October 2013, with the first school, Arvalee School, and a proposed completion of 2019 has been put forward. The construction is said to be costing in excess of £120million.[40]

OASIS Project

Environment Minister Alex Attwood announced in April 2013 that planning was approved for the Omagh Accessible Shared Inclusive Space (OASIS), a £4.5million facelift for Omagh's riverbank. The development is wholly funded by the European Union.

The project includes the construction of a new pedestrian bridge linked from Drumragh Avenue car park (beside the bus depot) to Old Market Place, a riverside walk, exercise areas, electronic information hub, artwork panels, games tables and fishing stands. It will also include the development of covered performance and stage area and a neutral civic space able to accommodate markets, concerts and general recreational activities partially occupying lands at Drumragh Avenue car park.[41]

Construction for the project began in March 2014, and is expected to last 12 months. The steel bow arch foot and cycle bridge was put into place on 26 July 2014.

Woodbrook Village

Woodbrook Village is an age exclusive residential housing development for the people over the age of forty-five and consists of 30 small homes, 12 apartments and a community building. The project was approved in January 2010 but was delayed until 2015 due to a depressed housing market.[42]

Education

Omagh has a large variety of educational institutions at all levels. Omagh is also the headquarters of the Western Education and Library Board (WELB), which is located in Campsie House on the Hospital Road.

Primary schools (elementary schools)

- Christ The King Primary School

- Gibson Primary School

- Gillygooley Primary School

- Holy Family Primary School

- Omagh County Primary School (and Nursery School)

- Omagh Integrated Primary School (and Nursery School)

- St Mary's Primary School

- St Conor's Primary School

- Gaelscoil na gCrann Irish language Primary school (and Naíscoil – Irish language nursery school)

- Recarson Primary School – Arvalee

Grammar/secondary school

- Christian Brothers Grammar School

Omagh College

Omagh College - Drumragh Integrated College

- Loreto Grammar School, Omagh

- Omagh Academy

- Omagh High School

- Sacred Heart College

Colleges/universities

Religious buildings

The following is a list of religious buildings in Omagh:

- Christ the King (Roman Catholic)

- Evangelical Presbyterian Church

- Gillygooley Presbyterian Church

- First Omagh Presbyterian

- Independent Methodist

- Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses

- Omagh Baptist

- Omagh Community Church (non-denominational)

- Omagh Free Presbyterian Church

- Omagh Gospel Hall (A company of Christians sometimes referred to as "open brethren")

- Omagh Methodist

- Sacred Heart (Roman Catholic)

- St. Columba's (Church of Ireland)

- St. Mary's ( Roman Catholic)

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church)

- Trinity Presbyterian Church

%2C_Omagh_-_geograph.org.uk_-_754121.jpg)

Media

Local newspapers and magazines

- Omagh Today

- Tyrone Advertiser

- Tyrone Constitution

- Tyrone Herald

- Ulster Herald

Local radio

- Q101.2 FM West – Broadcast from Omagh

- BBC Radio Ulster has a studio in the town.

Community Radio project Strule FM broadcast for four weeks in December 2008. The station featured a mixture of local interest programming and music programming produced by local radio presenters, historians and South West College Media/Music students. The station received the Bronze award for Community Radio at the 2009 Sony Radio Academy Awards.

Internet

Omagh was one of the first areas in Northern Ireland, outside the Belfast commuter belt, to transfer to broadband internet. Prior to this, the only means for internet connection was through dial-up connections.

In 2014, Omagh became one of only seven Northern Irish towns to receive superfast 4G mobile data coverage from the EE network.[43]

Sport

Gaelic games

Gaelic games, primarily Gaelic football, are the most popular sports in Omagh. The town has two Gaelic football clubs, Omagh St. Enda's, which plays its home games in Healy Park, and Drumragh Sarsfields, which plays its home games at Clanabogan.

Healy Park is the home of Tyrone GAA and the county's largest and main sports stadium located on the Gortin Road, has a capacity nearing 25,000,[44][45] and had the distinction of being the first Gaelic-games stadium in Ulster to have floodlights.[46]

The stadium now hosts the latter matches of the Tyrone Senior Football Championship, as well as Tyrone's home games, and other inter-county matches that require a neutral venue.[47]

Football

Omagh no longer has a top-flight local football team, since the demise of Omagh Town F.C. in 2005. Mountjoy United F.C., however, plays in the Northern Ireland Intermediate League. Strathroy Harps FC who are the only Omagh and Tyrone team to win the Irish junior cup twice 2012 2013

Rugby

Omagh's rugby team, Omagh Academicals (nicknamed the "Accies"), is an amateur team, made up of primarily of local players.

Cricket

Omagh Cavaliers Cricket Club located in Omagh.

People

Notable residents or people born in Omagh include:

- John Meahan, New Brunswick shipbuilder and politician, born and raised in Omagh

- Willie Anderson – Ireland Rugby Union International

- Charles Beattie – Auctioneer and briefly Member of Parliament

- Jimmy Kennedy (1902–1984) – Songwriter's Hall of Fame-inductee (Red Sails in the Sunset, Teddy Bears Picnic)[48]

- Benedict Kiely (1919–2007) – author (Land Without Stars)[49][50]

- Ciaran Maguire - Artist (Bath Spa graduate (4th place))

- Linda Martin – musician (Eurovision Song Contest-winner 1992)

- Patrick McAlinney (1913–1990) – Actor[51] (The Tomorrow People)

- Frankie McBride – country musician

- Joe McMahon – All-Ireland-winning Tyrone Gaelic footballer.

- Justin McMahon – All-Ireland-winning Tyrone Gaelic footballer.

- Gerard McSorley – actor[52] (Veronica Guerin), (Omagh)

- Alice Milligan - Protestant Nationalist poet

- Sam Neill – Jurassic Park actor (born in Omagh)[53]

- Pat Sharkey – Ipswich Town F.C. and Northern Irish football player in the 1970s.

- Ivan Sproule – current Northern Irish football international and Bristol City F.C. player.

- Juliet Turner – singer/songwriter

- Barley Bree - Irish Folk Group

- Arty McGlynn – International renowned guitarist.

- Gerald Grosvenor – 6th Duke of Westminster.

- Aaron McCormack – company CEO and one of the Young Global Leaders of the World Economic Forum

- Brian Friel – playwright was born in Killyclogher near Omagh.

- Aoife McArdle - Film Director

- Philip Turbett – bassoonist, clarinettist and saxophonist

- Janet Devlin - X-Factor Finalist 2011 (5th place)

- Sean McDermott - American Football manager and alumni of University of Liverpool Law School

- Phil Taggart - BBC Radio 1 DJ

- Martina Devlin - Journalist and author

Notes

- ↑ "2006 annual report in Ulster-Scots – North/South Ministerial Council" (PDF). Northsouthministerialcouncil.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Guide to Beaghmore stone circles – Ulster-Scots" (PDF). Department of the Environment. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- 1 2

- ↑ G. M. Miller, BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names (Oxford University Press, 1971), pg. 110

- ↑ "An Ómaigh/Omagh". Logainm.ie. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Gwynn, Aubrey; R. Neville Hadcock (1970). Medieval Religious Houses Ireland. Longman. pp. 267, 273, 400. ISBN 0-582-11229-X.

- 1 2 Baker, Michael H.C. (1972). Irish Railways since 1916. London: Ian Allan. pp. 153, 207. ISBN 0 7110 0282 7.

- ↑ Baker, 1972, pages 155, 209

- ↑ "Omagh gets green police station". Ulster TV. 14 September 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Suzanne Breen (22 April 2011). "Former Provos claim Kerr murder and vow more attacks". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Coolnagard". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Culmore". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Dergmoney". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Gortmore". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Killybrack". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Killyclogher". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Lammy". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Lisanelly". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Lisnamallard". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Lissan". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Mullaghmore". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Sadennan". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Placenames Project – Straughroy". Placenamesni.org. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ↑ "FOREST MANAGEMENT IN THE IRISH CLIMATE CONTD...........". Piffs.com. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase. 2013. Retrieved on July 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency". NISRA.gov.uk. 2010-09-27. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑

- ↑ "National Museums Northern Ireland - Welcome". Folkpark.com. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑

- 1 2 "Omagh station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- 1 2 Hajducki, S. Maxwell (1974). A Railway Atlas of Ireland. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. map 7. ISBN 0-7153-5167-2.

- ↑ FitzGerald, J.D. (1995). The Derry Road. Colourpoint Transport. Gortrush: Colourpoint Press. ISBN 1-898392-09-9.

- 1 2 Hajducki, op. cit., page xiii

- ↑ Hajducki, op. cit., map 39

- ↑ Baker, op. cit., pages 155, 209

- ↑ "New lines proposed in Northern Ireland rail plan". Railjournal.com. 3 May 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "Lisanelly: Work begins to create shared campus in Omagh". BBC. 23 October 2013.

- ↑ "Omagh’s riverbank area to get £4.5 million facelift". Ulsterherald.com. 2013-04-04. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Jobs boost as work begins on £5.8m project". Ulster Herald. April 14, 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ↑ "95% Geographic 4G Coverage | 4G Network". Ee.co.uk. 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "World Stadiums". Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Healy Park, Omagh". Ulster Colleges GAA. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Healy Park set to unveil lights". BBC News. 6 April 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Patrick McAlinney on IMDb

- ↑ Gerard McSorley on IMDb

- ↑ Sam Neill on IMDb

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Omagh. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Omagh. |

- Omagh District Council Website

- Omagh Chamber of Commerce & Industry Website

- Omagh Directory 1910

- Flickr group of Omagh photos

-

"Omagh". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Omagh". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.