Older Southern American English

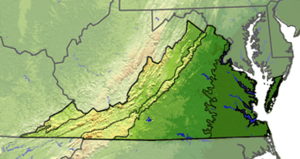

Older Southern American English was a set of American English dialects of the Southern United States, primarily spoken by White Southerners up until the American Civil War, moving towards a state of decline by the turn of the nineteenth century, further accelerated by World War II and again, finally, by the Civil Rights Movement.[1] These dialects have since largely given way, on a larger regional level, to a more unified and younger Southern American English, notably recognized today by a highly unique vowel shift and certain other vocabulary and accent characteristics. Some features unique to older Southern U.S. English persist today, though typically in only very localized dialects or speakers.

History

This group of American English dialects evolved over a period of several hundred years, primarily from older varieties of British English spoken by those who initially settled the area. Given that language is an entity that is constantly changing,[2] the English of the colonists was quite different from any variety of English being spoken today. The colonists who initially settled the Tidewater area spoke a variety of Early Modern English, which itself was very varied.[3] The older Southern dialects thus originated in large part from a mix of immigrants from the British Isles, who moved to the South in the 17th and 18th centuries, and the creole or post-creole speech of African slaves.

Atlantic Coast

The earliest English settlers of the colonies of Virginia and Massachusetts were mainly people from Southern England. However, Virginia received more colonists from the English West Country, bringing with them a distinctive dialect and vocabulary.

The Boston, Massachusetts; Norfolk, Virginia; and Charleston, South Carolina areas maintained strong commercial and cultural ties to England. Thus, the colonists and their descendants defined "social class" according to England's connotations. As the upper class English dialect changed, the dialects of the upper class Americans in these areas changed. Two examples are the "r-dropping" (or non-rhoticity) of the late 18th and early 19th century, resulting in the similar r-dropping found in Boston and parts of Virginia during the cultural "Old South," as well as the trap–bath split, which came to define these same two areas (and other areas of the South that imitated this phenomenon) but virtually no other region of the United States.

Given that there are over 2.8 million people in the area,[4] it is difficult to account for all variants of the local accent, which have largely been supplanted by newer Southern features. The area is home to several large military bases such as Naval Station Norfolk, Little Creek Amphibious Base, Oceana Naval Station, and Dam Neck Naval Base. Since a significant portion of the area's inhabitants are actually natives of other areas, there is constant linguistic exposure to other dialects. This exposure could be a reason why the younger generations do not exhibit most of the traditional features.

Phonology

General Older South

The phonologies of early Southern English in the United States were diverse. The following pronunciation features were very generally characteristic of the older Southern region as a whole:

| English diaphoneme | Old Southern phoneme | Example words |

|---|---|---|

| /aɪ/ | [aɪ~æɛ~aæ] | bride, prize, tie |

| [ai~aæ] | bright, price, tyke | |

| /æ/ | [æ] (or [æɛæ~ɐɛɐ], often before /d/) | cat, trap, yak |

| [æɛæ~eə] | hand, man, slam | |

| [æɛ~æe] | bath, can't, pass | |

| /ɑː/ | [ɑ] or [æ] | father, laager, palm |

| /ɑr/ | [ɒː] (non-rhotic) or [ɒɻ] (rhotic) |

ark, heart, start |

| /ɒ/ | [ɑ] | bother, lot, wasp |

| /eɪ/ | [ɛɪ~ɛi] or [eː~iː] (plantation possibility) |

face, rein, play |

| /ɛ/ | [ɛ] (or [eiə], often before /d/) | dress, egg, head |

| /ɜr/ | [ɜɪ~əɪ] or [ɜː] (non-rhotic before a consonant) or [ɜɚ] (non-rhotic elsewhere, or rhotic) |

nurse, search, worm |

| /iː/ | [iː~ɪi] | fleece, me, neat |

| /ɪ/ | [ɪ] | kit, mid, pick |

| happy, money, sari | ||

| /oʊ/ | [ɔu~ɒu] (after late 1800s) or [oː~uː] (plantation possibility) |

goat, no, throw |

| /ɔ/ | [ɔo] | thought, vault, yawn |

| cloth, lost, off | ||

| /ɔɪ/ | [ɔoɪ] or [oɛ~oə] (plantation possibility) |

choice, joy, loin |

| /ʌ/ | [ɜ] or [ʌ] (plantation possibility) |

strut, tough, won |

- Lack of Yod-dropping: Pairs like do and due, or toon and tune, were often distinct in these dialects because words like due, lute, new, etc. historically contained a diphthong similar to /juː/ (like the you sound in cute or puny).[6] (as England's RP standard pronunciation still does), but Labov et al. report that the only Southern speakers who make a distinction today use a diphthong /ɪu/ in such words.[7] They further report that speakers with the distinction are found primarily in North Carolina and northwest South Carolina, and in a corridor extending from Jackson to Tallahassee. For most of the South, this feature began disappearing after World War II.[8]

- Yod-coalescence: Words like dew were pronounced as "Jew", and Tuesday as "choose day."

- Wine–whine distinction: distinction between "w" and "wh" in words like "wine" and "whine", "witch and "which", etc.

- Horse–hoarse distinction: distinction between pairs of words like "horse" and "hoarse", "for" and "four", etc.

- Rhoticity and non-rhoticity: The pronunciation of the r sound only before or between vowels, but not after vowels, is known as "non-rhoticity" and was historically associated with the major plantation regions of the South: specifically, the entire Piedmont and most of the South's Atlantic Coast in a band going west towards the Mississippi River, as well as all of the Mississippi Embayment and some of the western Gulf Coastal Plain. This was presumably influenced by the non-rhotic East Anglia and London England pronunciation. Additionally, some older Southern dialects were even "variably non-rhotic in intra-word intervocalic contexts, as in carry [kʰæi]."[9] Rhotic accents of the older Southern dialects, which fully pronounce all historical r sounds, were somewhat rarer and primarily spoken in Appalachia, the eastern Gulf Coastal Plain, and the areas west of the Mississippi Embayment.[10]

- Palatalization of /k/ and /g/ before /ɑr/: Especially in the older South along the Atlantic Coast, the consonants /k/ (as in key or coo) and /ɡ/ (as in guy or go), when before the sound /ɑːr/ (as in car or barn), were often pronounced with the tongue fronted towards the hard palate. Thus, for example, garden in older Southern was something like "gyah(r)den" [ˈgjɑː(ɹ)dən] and "cart" like "kyah(r)t" [cʰjɑː(ɹ)t]. This pronunciation feature was in decline by the late 1800s.[8]

- Lack or near-lack of /aɪ/ glide weakening: The gliding vowel in words like prize (but less commonly in price or other situations of this vowel appearing before a voiceless consonant) commonly has a "weakened" glide today in the South; however, this only became a documented feature since the last quarter of the 1800s and was otherwise absent or inconsistent in earlier Southern dialects. Today, the lack of glide weakening persists in the High Tider and updated Lowcountry accents. Full weakening has become a defining feature only of the modern Southern dialects, particularly the most advanced sub-varieties.[11]

- Mary–marry–merry distinction: Unlike most of the U.S. and modern Southern, older Southern did not merge the following three vowels before /r/: [e~eə] (as in Mary), [æ] (as in marry), and [ɛ] (as in merry). Although the three are now merging or merged in modern Southern English, the "marry" class of words remains the least likely among modern Southerners to merge with the other two.[12]

- Clear /l/ between front vowels: Unlike modern Southern and General American English's universally "dark" /l/ sound (often represented as [ɫ]), older Southern pronunciation had a "clear" (i.e. non-velarized) /l/ sound whenever /l/ appears between front vowels, as in the words silly, mealy, Nellie, etc.[8]

- Was, what and of pronounced with [ɑ]: The stressed word what, for example, rhymed with cot (not with cut, as it does elsewhere in the U.S.).[13]

- No happy-tensing: The final vowel of words like happy, silly, monkey, parties, etc. were not tensed as they are in newer Southern and other U.S. dialects, meaning that this vowel sounded more like the [ɪ] of fit than the [i] of feet.

- /oʊ/, as in goat, toe, robe, etc., kept a back starting place (unlike most Southern since World War II, but like most Northern U.S. dialects today); this became an opener [ɔu~ɒu] in the early 1900s.[13] The modern fronted form of the Atlantic South started as far back as the 1800s in northeastern North Carolina, in the form [ɜy], but only spread slowly, until accelerating after World War II.[14]

- /ʃr/ pronounced as [sɹ] (e.g. causing shrimp, shrub, etc. to sound like srimp, srub, etc.); this feature was reported earliest in Virginia.[15]

Plantation South

Older speech of the Plantation South or "Black Belt" included those features above, plus:

- Non-rhoticity: R-dropping historically occurred in the greater central sections of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, and in coastal Texas and some other coastal communities of the Gulf states. Rhoticity (or r-fulness) was more likely outside of the Black Belt proper, in the southernmost sections of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, as well as in northern Florida, western Louisiana, and eastern Texas.[16]

- Trap–bath split: Words like bath, dance, and ask, used a different vowel ([æ̈ɛ~æ̈e]) than words like trap, cat, and rag ([æ~æ̈ɛæ̈]).[17] A similarly-organized (though different-sounding) split occurs in Standard British English.

- /eɪ/, as in face, was inconsistently pronounced [e̝ː].[18]

- /oʊ/, as in goat, was inconsistently pronounced [o̝ː].[19]

- /ʌ/, as in strut, was conservative.[20]

- /ɔɪ/, as in choice, was [oɛ~oə].[21]

Appalachia

Due to the former isolation of some regions of the Appalachian South, the Appalachian accent may be difficult for some outsiders to understand. This dialect is also rhotic, meaning speakers pronounce Rs wherever they appear in words, and sometimes when they do not (for example, "worsh" or "warsh" for "wash"). Because of the extensive length of the mountain chain, noticeable variation also exists within this subdialect.

The Southern Appalachian dialect can be heard, as its name implies, in north Georgia, north Alabama, east Tennessee, northwestern South Carolina, western North Carolina, eastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia, western Maryland, and West Virginia. Southern Appalachian speech patterns, however, are not entirely confined to the mountain regions previously listed.

Almost always, the common thread in the areas of the South where a rhotic version of the dialect is heard is a traceable line of descent from Scots or Scots-Irish ancestors amongst its speakers. The dialect is also not devoid of early influence from Welsh settlers, the dialect retaining the Welsh English tendency to pronounce words beginning with the letter "h" as though the "h" were silent; for instance "humble" often is rendered "umble".

Researchers have noted that the dialect retains a lot of vocabulary with roots in Scottish "Elizabethan English" owing to the make-up of the early European settlers to the area.[22]

Charleston

The Lowcountry, most famously centering on the cities of Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia, once constituted its own entirely unique English dialect region. Traditionally often recognized as a Charleston accent, it included these additional features, most of which no longer exist today:[23]

- Cheer–chair merger towards [ɪə~eə].[24]

- Non-rhoticity (or r-dropping).

- A possibility of both variants of Canadian raising:

- /eɪ/ pronounced as [ɪə~eə] in a closed syllable, [ɪː~eː] in an open syllable.[26]

- /oʊ/ pronounced as [oə~uə] in a closed syllable, [o~u] in an open syllable.[27]

- /ɔː/ pronounced as [ɔ~o].[28]

- /ɑː/ pronounced as [æ].[29]

- /ɜːr/ pronounced as [əɪ].[17]

Pamlico and Chesapeake

The "Down East" Outer Banks coastal region of Carteret County, North Carolina, and adjacent Pamlico Sound, including Ocracoke and Harkers Island, are known for additional features, some of which are still spoken today by generations-long residents of its unincorporated coastal and island communities, which have largely been geographically and economically isolated from the rest of North Carolina and the South since their first settlement by English-speaking Europeans. The same is true for the very similar dialect area of the Delmarva (Delaware–Maryland–Virginia) Peninsula and neighboring islands in the Chesapeake Bay, such as Tangier and Smith Island. These two regions historically share many common pronunciation features, sometimes collectively called a High Tider (or "Hoi Toider") accent, including:

- Rhoticity (or r-fulness, like in most U.S. English, but unlike in most other older Atlantic Southern dialects)

- /aɪ/, such as the vowel in the words high tide, retaining its glide and being pronounced beginning further back in the mouth, as [ɑe] or even rounded [ɒe~ɐɒe], often stereotyped as sounding like "hoi toid," giving Pamlico Sound's residents the name "High Tiders."[30]

- /æ/ is raised to [ɛ] (so cattle sounds like kettle); /ɛ/ is raised to [e~ɪ] (so that mess sounds like miss); and, most prominently, /ɪ/ is raised to [i] (so fish sounds like feesh).[31] This mirrors the second and third stages of the Southern Vowel Shift (see under "Newer phonology"), despite this particular accent never participating in the very first stage of the shift.

- /ɔː/ pronounced as [ɔ~o], similar to modern Australian or London English.

- /aʊ/, as in loud, town, scrounge, etc., pronounced with a fronted glide as [aɵ~aø~aε].[24] Before a voiceless consonant, this same phoneme is [ɜʉ~ɜy].[25]

- /ɛər/, as in chair, square, bear, etc., as [æɚ].[24]

- Card–cord merger since at least the 1800s in the Delmarva Peninsula.[24]

Piedmont and Tidewater Virginia

The major central (Piedmont) and eastern (Tidewater) regions of Virginia, excluding Virginia's Eastern Shore, once spoke in a way long associated with the upper or aristocratic plantation class in the Old South, often known as a Tidewater accent. Additional phonological features of this Atlantic Southern variety included:

- Non-rhoticity (or r-dropping).

- Trap–bath split: pronunciation of the bath set of words as [æ̈ɛ~æ̈e], different from the trap set of words as [æ~æ̈ɛæ̈].[17]

- A possibility of both variants of Canadian raising:

- /eɪ/ pronounced as [ɛ] in certain words, making bake sound like "beck", and afraid like "uh Fred."

- In Tidewater Virginia particularly:

- Some of the "bath" words (aunt, rather, and, earlier, pasture, etc.) pronounced farther back in mouth, as [ɒ~ɑ].

- /ɜːr/, as in bird, earth, flirt, etc. pronounced as [ɜ], similar to modern London English.

- "Broad a" (as in palm, father, spa, etc.) shifted towards a rounded [ɒː], potentially causing, for example, palm and harm to rhyme.

Southern Louisiana

Southern Louisiana, as well as some of southeast Texas (Houston to Beaumont), and coastal Mississippi, feature a number of dialects influenced by other languages beyond English. Most of southern Louisiana constitutes Acadiana, dominated for hundreds of years by monolingual speakers of Cajun French,[32] which combines elements of Acadian French with other French and Spanish words. This French dialect is spoken by many of the older members of the Cajun ethnic group and is said to be dying out. A related language called Louisiana Creole also exists. The older English of Southern Louisiana did not participate in certain general older Southern English phenomena, for example lacking the Plantation South's trap–bath split and the fronting of /aʊ/.[33]

New Orleans English was likely developing in the early 1900s, in large part due to dialect influence from New York City immigrants in New Orleans.

Grammar and vocabulary

- Zero copula in third person plural and second person. This is historically a consequence of R-dropping, with e.g. you're merging with you.

- You [Ø] taller than Louise.

- They [Ø] gonna leave today (Cukor-Avila, 2003).

- Use of the circumfix a- . . . -in' in progressive tenses.

- He was a-hootin' and a-hollerin'.

- The wind was a-howlin'.

- The use of like to to mean nearly; liked to merging into like to

- I like to had a heart attack. (I nearly had a heart attack)

- The use of the simple past infinitive vs present perfect infinitive.

- I like to had. vs I like to have had.

- We were supposed to went. vs We were supposed to have gone.

- Use of "yonder" as a locative in addition to its more widely attested use as an adjective.

- They done gathered a mess of raspberries in them woods down yonder.

Current projects

A project devised by Old Dominion University Assistant Professor Dr. Bridget Anderson entitled Tidewater Voices: Conversations in Southeastern Virginia was initiated in late 2008.[34] In collecting oral histories from natives of the area, this study offers insight to not only specific history of the region, but also to linguistic phonetic variants native to the area as well. This linguistic survey is the first of its kind in nearly forty years.[35] The two variants being analyzed the most closely in this study are the /aʊ/ diphthong as in house or brown and post-vocalic r-lessness as in /ˈfɑːðə/ for /ˈfɑːðər/.

References

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:4)

- ↑ Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an Accent. New York, New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Wolfram, W, & Schilling-Estes, N. (2006). American English. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑

- ↑ Thomas (2006:7–14)

- ↑ Even in 2012 Random House Dictionary labels due, new and tune as having the /yu/ sound as a variant pronunciation.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:53–54)

- 1 2 3 Thomas (2006:17)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:7–14)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:3, 16)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:10–11)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:15)

- 1 2 Thomas (2006:6)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:10)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:18)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:16)

- 1 2 3 Thomas (2006:8)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:9)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:10)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:7)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:11)

- ↑ "The Dialect of the Appalachian People". Wvculture.org. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:259–260)

- 1 2 3 4 (Thomas (2006:12)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas (2006:11–12)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:9)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:10)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:9)

- ↑ Thomas (2006:9)

- ↑ (Thomas (2006:4, 11)

- ↑ Wolfram, Walt (1997). Hoi Toide on the Outer Banks: The Story of the Ocracoke Brogue. University of North Carolina Press. p. 61.

- ↑ Dubois, Sylvia and Barbara Horvath (2004). "Cajun Vernacular English: phonology." In Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (Ed). A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 412-4.

- ↑ Thomas (2006:8, 11)

- ↑ Batts, Denise (January 22, 2009). "ODU team records area's accent - English with 'deep roots'". hamptonroads.com. The Virginian Pilot. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ↑ Watson, Denise (2009-01-22). "ODU team records area's accent - English with 'deep roots' | HamptonRoads.com | PilotOnline.com". HamptonRoads.com. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- Thomas, Erik R. (2006), "Rural White Southern Accents" (PDF), Atlas of North American English (online), Walter de Gruyter

- Lippi-Green, Rosina. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. New York: Routedge.

- Shores, David L. (2000). Tangier Island: place, people, and talk. Cranbury, New Jersey. Associated University Presses.

- Wolfram, W, & Schilling-Estes, N. (2006). American English. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

External links

- Example of an old Virginia accent spoken by a Richmond, Virginia native, featured in the George Mason University Linguistics program Speech Accent Archive.

- "Virginia’s Many Voices," Fairfax County, Virginia Library

- International Dialects of English Archive, "Dialects Of Virginia"

- "A National Map of the Regional Dialects of American English," by William Labov, Sharon Ash and Charles Boberg, The Linguistics Laboratory in the Department of Linguistics at University of Pennsylvania

- Hamptonroads.com