Ancient South Arabian script

| Ancient South Arabian script | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Languages | Ge'ez, Old South Arabian |

Time period | c. 9th century BC to 7th century AD |

Parent systems |

Proto-Sinaitic

|

Child systems | Ge'ez[1][2] |

Sister systems | Phoenician alphabet |

| Direction | Right-to-left |

| ISO 15924 |

Sarb, 105 |

Unicode alias | Old South Arabian |

| U+1BC0–U+10A7F | |

The ancient Yemeni alphabet (Old South Arabian ms3nd; modern Arabic: المُسنَد musnad) branched from the Proto-Sinaitic script in about the 9th century BC. It was used for writing the Old South Arabian languages of the Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramautic, Minaean, Himyaritic, and Ge'ez in Dʿmt. The earliest inscriptions in the alphabet date to the 9th century BC in the Northern Red Sea Region, Eritrea.[3] There are no vowels, instead using the mater lectionis to mark them.

Its mature form was reached around 500 BC, and its use continued until the 6th century, including Ancient North Arabian inscriptions in variants of the alphabet, when it was displaced by the Arabic alphabet.[4] In Ethiopia and Eritrea it evolved later into the Ge'ez script,[1][2] which, with added symbols throughout the centuries, has been used to write Amharic, Tigrinya and Tigre, as well as other languages (including various Semitic, Cushitic, and Nilo-Saharan languages).

Sign inventory

| (epigraphic) Old Yemeni alphabet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character Transcription IPA |

𐩠 h [h] |

𐩡 l [l] |

𐩢 ḥ [ħ] |

𐩣 m [m] |

𐩤 q [q] |

𐩥 w [w] |

𐩦 s2 [ɬ] |

𐩧 r [r] |

𐩨 b [b] |

𐩩 t [t] |

𐩪 s1 [ʃ] |

𐩫 k [k] |

𐩬 n [n] |

𐩭 ḫ [x] |

𐩯 s3 [s̪] |

𐩰 f [f] |

𐩱 a [a] |

𐩲 ʿ [ʕ] |

𐩳 ḍ [ɬˤ] |

𐩴 g [ɡ] |

𐩵 d [d] |

𐩶 ġ [ɣ] |

𐩷 ṭ [tˤ] |

𐩸 z [z] |

𐩹 ḏ [ð] |

𐩺 y [j] |

𐩻 ṯ [θ] |

𐩮 ṣ [sˤ] |

𐩼 ẓ [θˤ] | |||

| Other transcriptions | ś,š | š,s | s,ś | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By shape | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character Transcription IPA |

r [r] |

ʿ [ʕ] |

w [w] |

q [q] |

y [j] |

ṯ [θ] |

ṣ [tsˤ] |

ẓ [θˤ] |

h [h] |

ḥ [ħ] |

ḫ [x] |

a [a] |

s1 [s] |

k [k] |

ġ [ɣ] |

b [b] |

n [n] |

g [ɡ] |

l [l] |

m [m] |

s2 [ɬ] |

s3 [s̪] |

t [t] |

f [f] |

z [z] |

d [d] |

ḏ [ð] |

ḍ [ɬˤ] |

ṭ [tˤ] | |||

| Circle | Y | Π | Vertical | Diagonal | Box | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zabūr script

Zabūr is the name of the cursive form of the South Arabian script that was used by the ancient Yemenis (Sabaeans) in addition to their monumental script, or musnad (see, e.g., Ryckmans, J., Müller, W. W., and ‛Abdallah, Yu., Textes du Yémen Antique inscrits sur bois. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 1994 (Publications de l'Institut Orientaliste de Louvain, 43)).

The cursive zabūr script—also known as "South Arabian minuscules"[5]—was used by the ancient Yemenis to inscribe everyday documents on wooden sticks in addition to the rock-cut monumental musnad letters displayed above. As yet only about one thousand such texts have been discovered, of which perhaps some 26 have been published; this is partly due to the difficulty of reading the minuscule script.

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

|

Properties

- It is usually written from right to left but can also be written from left to right. When written from left to right the characters are flipped horizontally (see the photo).

- The spacing or separation between words is done with a vertical bar mark (|).

- Letters in words are not connected together.

- It does not implement any diacritical marks (dots, etc.), differing in this respect from the modern Arabic alphabet.

Unicode

The South Arabian alphabet was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

The Unicode block, called Old South Arabian, is U+10A60–U+10A7F.

Note that U+10A7D OLD SOUTH ARABIAN NUMBER ONE (𐩽) represents both the numeral one and a word divider.[6]

| Old South Arabian[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10A6x | 𐩠 | 𐩡 | 𐩢 | 𐩣 | 𐩤 | 𐩥 | 𐩦 | 𐩧 | 𐩨 | 𐩩 | 𐩪 | 𐩫 | 𐩬 | 𐩭 | 𐩮 | 𐩯 |

| U+10A7x | 𐩰 | 𐩱 | 𐩲 | 𐩳 | 𐩴 | 𐩵 | 𐩶 | 𐩷 | 𐩸 | 𐩹 | 𐩺 | 𐩻 | 𐩼 | 𐩽 | 𐩾 | 𐩿 |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

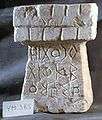

Gallery of some inscriptions

- Photos from National Museum of Yemen:

- Photos from Yemen Military Museum:

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William, eds. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 89, 98, 569–570. ISBN 978-0195079937.

- 1 2 Gragg, Gene (2004). "Ge'ez (Aksum)". In Woodard, Roger D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. ISBN 0-521-56256-2.

- ↑ Fattovich, Rodolfo, "Akkälä Guzay" in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz KG, 2003, p. 169.

- ↑ Ibn Durayd, Ta‘līq min amāli ibn durayd, ed. al-Sanūsī, Muṣṭafā, Kuwait 1984, p. 227 (Arabic). The author purports that a poet from the Kinda tribe in Yemen who settled in Dūmat al-Ǧandal during the advent of Islam told of how another member of the Yemenite Kinda tribe who lived in that town taught the Arabic script to the Banū Qurayš in Mecca, and that their use of the Arabic script for writing eventually took the place of musnad, or what was then the Sabaean script of the kingdom of Ḥimyar: "You have exchanged the musnad of the sons of Ḥimyar / which the kings of Ḥimyar were wont to write down in books."

- ↑ Stein 2005.

- ↑ Maktari, Sutlan; Mansour, Kamal. "N3395: Proposal to encode Old South Arabian script" (PDF). Retrieved 2 August 2014.

References

- Stein, Peter (2005). "The Ancient South Arabian Minuscule Inscriptions on Wood: A New Genre of Pre-Islamic Epigraphy". Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch Genootschap "Ex Oriente Lux". 39: 181–199.

- Stein, Peter (2010). Die altsüdarabischen Minuskelinschriften auf Holzstäbchen aus der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek in München.

- Beeston, A.F.L. (1962). "Arabian Sibilants". Journal of Semitic Studies. 7 (2): 222–233. doi:10.1093/jss/7.2.222.

- Francaviglia Romeo, Vincenzo (2012). Il trono della regina di Saba, Artemide, Roma. pp. 149–155..