Galician-Portuguese

| Galician-Portuguese | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Kingdom of Galicia, County of Portugal |

| Region | North-west Iberia |

| Era | Attested 870 A.D.; by 1400 had split into Galician, Fala, and Portuguese.[1] |

|

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

079 | |

| Glottolog | None |

| |

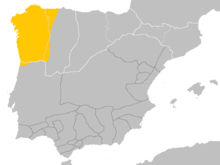

Galician-Portuguese (Galician: galego-portugués or galaico-portugués, Portuguese: galego-português or galaico-português), also known as Old Portuguese or Medieval Galician, was a West Iberian Romance language spoken in the Middle Ages, in the northwest area of the Iberian Peninsula. Alternatively, it can be considered a historical period of the Galician and Portuguese languages.

Galician-Portuguese was first spoken in the area bounded in the north and west by the Atlantic Ocean, and by the Douro River in the south, comprising Galicia and northern Portugal, but it was later extended south of the Douro by the Reconquista.

It is the common ancestor of modern Portuguese, Galician, Eonavian and Fala varieties, all of which maintain very limited level of mutual intelligibility. The term "Galician-Portuguese" also designates the subdivision of the modern West Iberian group of Romance languages.

Language

Origins and history

Galician-Portuguese developed in the region of the former Roman province of Gallaecia, from the Vulgar Latin (common Latin) that had been introduced by Roman soldiers, colonists and magistrates during the time of the Roman Empire. Although the process may have been slower than in other regions, the centuries of contact with Vulgar Latin, after a period of bilingualism, completely extinguished the native languages, leading to the evolution of a new variety of Latin with a few Gallaecian features.[2][3]

Gallaecian and Lusitanian influences were absorbed into the local Vulgar Latin dialect, which can be detected in some Galician-Portuguese words as well as in placenames of Celtic and Iberian origin like Bolso.[4] In general, the more cultivated variety of Latin spoken by the Hispano-Roman elites in Roman Hispania had a peculiar regional accent, referred to as Hispano ore and agrestius pronuntians.[5] The more cultivated variety of Latin coexisted with the popular variety. It is assumed that the Pre-Roman languages spoken by the native people, each used in a different region of Roman Hispania, contributed to the development of several different dialects of Vulgar Latin and that these diverged increasingly over time, eventually evolving into the early Romance Languages of the Iberia.

It is believed that by 600, Vulgar Latin was no longer spoken in the Iberian Peninsula.[6] An early form of Galician-Portuguese was already spoken in the Kingdom of the Suebi and by the year 800 Galician-Portuguese had already become the vernacular of northwestern Iberia.[6] The first known phonetic changes in Vulgar Latin, which began the evolution to Galician-Portuguese, took place during the rule of the Germanic groups, the Suebi (411–585) and Visigoths (585–711).[6] And the Galician-Portuguese "inflected infinitive" (or "personal infinitive")[7] and the nasal vowels may have evolved under the influence of local Celtic languages[8][9] (as in Old French). The nasal vowels would thus be a phonologic characteristic of the Vulgar Latin spoken in Roman Gallaecia, but they are not attested in writing until after the 6th and 7th centuries.[10]

The oldest known document to contain Galician-Portuguese words, found in northern Portugal, is called the Doação à Igreja de Sozello and dated to 870 but otherwise composed in Late/Middle Latin.[11] Another document, from 882, also containing some Galician-Portuguese words is the Carta de dotação e fundação da Igreja de S. Miguel de Lardosa.[12] In fact, many Latin documents written in Portuguese territory contain Romance forms.[13] The Notícia de fiadores, written in 1175, is thought by some to be the oldest known document written in Galician-Portuguese.[14]

The Pacto dos irmãos Pais, recently discovered (and possibly dating from before 1173), has been said to be even older, but despite the enthusiasm of some scholars, it has been shown that the documents are not really written in Galician-Portuguese but are in fact a mixture of Late Latin and Galician-Portuguese phonology, morphology and syntax.[15] The Noticia de Torto, of uncertain date (c. 1214?), and the Testamento de D. Afonso II (27 June 1214) are most certainly Galician-Portuguese.[14] The earliest poetic texts (but not the manuscripts in which they are found) date from c. 1195 to c. 1225. Thus, by the end of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th there are documents in prose and verse written in the local Romance vernacular.

Literature

Galician-Portuguese had a special cultural role in the literature of the Christian kingdoms of Crown of Castile (Kingdoms of Castile, Leon and Galicia,part of the medieval NW Iberian Peninsula) comparable to the Catalan Language of the Crown of Aragon (Principality of Catalonia and Kingdoms of Aragon, Valencia and Majorca, NE medieval Iberian Peninsula), or that of Occitan in France and Italy during the same historical period. The main extant sources of Galician-Portuguese lyric poetry are these:

- The four extant manuscripts of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (written by Alfonso X the Wise, king of Castile, Leon and Galicia from 1252–1284)

- Cancioneiro da Ajuda

- Cancioneiro da Vaticana

- Cancioneiro Colocci-Brancuti, also known as Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional (Lisbon)

- Cancioneiro dun Grande de Espanha

- Pergaminho Vindel

- Pergaminho Sharrer

- Os 5 lais de Bretanha

- Tenzón entre Afonso Sánchez e Vasco Martíns de Resende

The language was used for literary purposes from the final years of the 12th century to roughly the middle of the 14th century in what are now Spain and Portugal and was, almost without exception, the only language used for the composition of lyric poetry. Over 160 poets are recorded, among them Bernal de Bonaval, Pero da Ponte, Johan Garcia de Guilhade, Johan Airas de Santiago, and Pedr' Amigo de Sevilha. The main secular poetic genres were the cantigas d'amor (male-voiced love lyric), the cantigas d'amigo (female-voiced love lyric) and the cantigas d'escarnho e de mal dizer (including a variety of genres from personal invective to social satire, poetic parody and literary debate).[16]

All told, nearly 1,700 poems survive in these three genres, and there is a corpus of over 400 cantigas de Santa Maria (narrative poems about miracles and hymns in honor of the Holy Virgin). The Castilian king Alfonso X composed his cantigas de Santa Maria and his cantigas de escárnio e maldizer in Galician-Portuguese, even though he used Castilian for prose.

King Dinis of Portugal, who also contributed (with 137 extant texts, more than any other author) to the secular poetic genres, made the language official in Portugal in 1290. Until then, Latin had been the official (written) language for royal documents; the spoken language did not have a name and was simply known as lingua vulgar ("ordinary language", that is Vulgar Latin) until it was named "Portuguese" in King Dinis' reign. "Galician-Portuguese" and português arcaico ("Old Portuguese") are modern terms for the common ancestor of modern Portuguese and modern Galician. Compared to the differences in Ancient Greek dialects, the alleged differences between 13th-century Portuguese and Galician are trivial.

Divergence

As a result of political division, Galician-Portuguese lost its unity when the County of Portugal separated from the Kingdom of Galicia in 1128 (a dependent kingdom of Leon) to establish the Kingdom of Portugal. The Galician and Portuguese versions of the language then diverged over time as they followed independent evolutionary paths.

As Portugal's territory was extended southward during the Reconquista, the increasingly distinctive Portuguese language was adopted by the people in those regions, supplanting the earlier Arabic and other Romance/Latin languages that were spoken in these conquered areas during the Moorish era. Meanwhile, Galician was influenced by the neighboring Leonese language, especially during the time of kingdoms of Leon and Leon-Castile, and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it has been influenced by Castilian. Two cities at the time of separation, Braga and Porto, were within the County of Portugal and have remained within Portugal. Further north, the cities of Lugo, A Coruña and the great medieval centre of Santiago de Compostela remained within Galicia.

Galician was preserved in Galicia in the modern era because those who spoke it were the majority rural or "uneducated" population living in the villages and towns, and Castilian was taught as the "correct" language to the bilingual educated elite in the cities. Because until comparatively recently most Galicians lived in many small towns and villages in a remote and mountainous land, the language changed very slowly and was only very slightly influenced from outside the region. That situation made Galician remain the vernacular of Galicia until the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries and is still widely spoken; most Galicians today are bilingual. Modern Galician was only officially recognized by the Second Spanish Republic in the 1930s as a co-official language with Castilian within Galicia. The recognition was revoked by the regime of Francisco Franco but was restored after his death.

The linguistic classification of Galician and Portuguese is still discussed today. There are those among Galician independence groups who demand their reunification as well as Portuguese and Galician philologists who argue that both are dialects of a common language rather than two separate ones.

The Fala language, spoken in a small region of the Spanish autonomous community of Extremadura, underwent a similar development as Galician.

Galician is the regional language of Galicia (sharing co-officiality with Spanish), and it is spoken by the majority of its population. Portuguese continues to grow and, today, is the sixth most spoken language in the world.

Phonology

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | β1 | f | s | z | ʃ | ʒ2 | ||||||

| Affricates | ts | dz | tʃ | dʒ2 | ||||||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | ||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||||

- 1 /β/ eventually shifted to /v/ in central and southern Portugal (and hence in Brazil) and merged with /b/ in northern Portugal and Galicia.

- 2 [ʒ] and [dʒ] probably occurred in complementary distribution.

/s/ and /z/ were apico-alveolar while /ts/ and /dz/ were lamino-alveolar. Later in the history of Portuguese, all the affricate sibilants became fricatives, with the apico-alveolar and lamino-alveolar sibilants remaining distinct for a time but eventually merging in most dialects. See History of Portuguese for more information.

A stanza of Galician-Portuguese lyric

|

Proençaes soen mui ben trobar — King Dinis of Portugal (1271–1325) |

Provençal poets know how to compose very well |

Oral traditions

There has been a sharing of folklore in the Galician-Portuguese region going back to prehistoric times. As the Galician-Portuguese language spread south with the Reconquista, supplanting Mozarabic, this ancient sharing of folklore intensified. In 2005 the governments of Portugal and Spain jointly proposed that Galician-Portuguese oral traditions be made part of the Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. The work of documenting and transmitting that common culture involves several universities and other organizations.

Galician-Portuguese folklore is rich in oral traditions. These include the cantigas ao desafio or regueifas, duels of improvised songs, many legends, stories, poems, romances, folk songs, sayings and riddles, and ways of speech that still retain a lexical, phonetic, morphological and syntactic similarity.

Also part of the common heritage of oral traditions are the markets and festivals of patron saints and processions, religious celebrations such as the magosto, entroido or Corpus Christi, with ancient dances and tradition – like the one where Coca the dragon fights with Saint George; and also traditional clothing and adornments, crafts and skills, work-tools, carved vegetable lanterns, superstitions, traditional knowledge about plants and animals. All these are part of a common heritage considered in danger of extinction as the traditional way of living is replaced by modern life, and the jargon of fisherman, the names of tools in traditional crafts, and the oral traditions which form part of celebrations are slowly forgotten.

A Galician-Portuguese "baixo-limiao" lect is spoken in several villages. In Galicia it is spoken in Entrimo and Lobios and in northern Portugal in Terras de Bouro (lands of the Buri) and Castro Laboreiro including the mountain town (county seat) of Soajo and surrounding villages.[17]

See also

About the Galician-Portuguese language

- Cantiga de amigo

- Eonavian

- Fala language

- Galician language

- History of Portuguese

- Portuguese language

- Reintegrationism

About Galician-Portuguese culture

References

- ↑ Galician-Portuguese at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- ↑ Luján Martínez, Eugenio R. (3 May 2006). "The Language(s) of the Callaeci" (PDF). e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 715–748. ISSN 1540-4889.

- ↑ Piel, Joseph-Maria (1989). "Origens e estruturação histórica do léxico português". Estudos de Linguística Histórica Galego-Portuguesa (PDF). Lisboa: IN-CM. pp. 9–16.

- ↑ A Toponímia Céltica e os vestígios de cultura material da Proto-História de Portugal. Freire, José. Revista de Guimarães, Volume Especial, I, Guimarães, 1999, pp. 265–275. (PDF) . Retrieved on 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Adams, J. N. (2003). Bilingualism and the Latin language (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81771-4. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 "As origens do romance galego-português". Instituto Luis de Camões.

- ↑ Alinei, Mario; Benozzo, Francesco (2008). "Alguns aspectos da Teoria da Continuidade Paleolítica aplicada à região galega" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Comparative Grammar of Latin 34 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ethnologic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (circa 200 B.C.). Arkeotavira.com. Retrieved on 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Fonética histórica

- ↑ The oldest document containing traces of Galician-Portuguese, a.D. 870. Novomilenio.inf.br. Retrieved on 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Charter of the Foundation of the Church of S. Miguel de Lardosa, a.D. 882. Fcsh.unl.pt. Retrieved on 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Norman P. Sacks, The Latinity of Dated Documents in the Portuguese Territory, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1941

- 1 2 The oldest texts written in Galician-Portuguese

- ↑ Ivo Castro, Introdução à História do Português. Geografia da Língua. Português Antigo. [Lisbon: Colibri, 2004], pp. 121–125, and by A. Emiliano, cited by Castro

- ↑ Many of these texts correspond to the Greek psogoi mentioned by Aristotle [Poetics 1448b27] and exemplified in the verses of iambographers such as Archilochus and Hipponax.

- ↑ Ribeira, José Manuel. "A Fala Galego-Portuguesa da Baixa Limia e Castro Laboreiro: Integrado no Projecto para a declaraçom de Património da Humanidade da Cultura Imaterial Galego-Portuguesa" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2011.

Bibliography

Manuscripts containing Galician-Portuguese ('secular') lyric (cited from Cohen 2003 [see below under critical editions]):

- A = "Cancioneiro da Ajuda", Palácio Real da Ajuda (Lisbon).

- B = Biblioteca Nacional (Lisbon), cod. 10991.

- Ba = Bancroft Library (University of California, Berkeley) 2 MS DP3 F3 (MS UCB 143)

- N = Pierpont Morgan Library (New York), MS 979 (= PV).

- S = Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (Lisbon), Capa do Cart. Not. de Lisboa, N.º 7-A, Caixa 1, Maço 1, Livro 3.

- V = Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, cod. lat. 4803.

- Va = Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, cod. lat. 7182, ff. 276rº – 278rº

Manuscripts containing the Cantigas de Santa Maria:

- E = Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo (El Escorial), MS B. I. 2.

- F = Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale (Florence), Banco Rari 20.

- T = Real Monasterio de San Lorenzo (El Escorial), MS T. I. 1.

- To = Biblioteca Nacional (Madrid), cod. 10.069 ("El Toledano")

Critical editions of individual genres of Galician-Portuguese poetry (note that the cantigas d'amor are split between Michaëlis 1904 and Nunes 1932):

- Cohen, Rip. (2003). 500 Cantigas d' Amigo: Edição Crítica / Critical Edition (Porto: Campo das Letras).

- Lapa, Manuel Rodrigues (1970). Cantigas d'escarnho e de mal dizer dos cancioneiros medievais galego-portugueses. Edição crítica pelo prof. –. 2nd ed. Vigo: Editorial Galaxia [1st. ed. Coimbra, Editorial Galaxia, 1965] with "Vocabulário").

- Mettmann, Walter. (1959–1972). Afonso X, o Sabio. Cantigas de Santa Maria. 4 vols ["Glossário", in vol. 4]. Coimbra: Por ordem da Universidade (republished in 2 vols. ["Glossário" in vol. 2] Vigo: Edicións Xerais de Galicia, 1981; 2nd ed.: Alfonso X, el Sabio, Cantigas de Santa Maria, Edición, introducción y notas de –. 3 vols. Madrid: Clásicos Castália, 1986–1989).

- Michaëlis de Vasconcellos, Carolina. (1904). Cancioneiro da Ajuda. Edição critica e commentada por –. 2 vols. Halle a.S., Max Niemeyer (republished Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional – Casa de Moeda, 1990).

- Nunes, José Joaquim. (1932). Cantigas d'amor dos trovadores galego-portugueses. Edição crítica acompanhada de introdução, comentário, variantes, e glossário por –. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade (Biblioteca de escritores portugueses) (republished by Lisboa: Centro do Livro Brasileiro, 1972).

On the biography and chronology of the poets and the courts they frequented, the relation of these matters to the internal structure of the manuscript tradition, and myriad relevant questions in the field, please see:

- Oliveira, António Resende de (1987). "A cultura trovadoresca no ocidente peninsular: trovadores e jograis galegos", Biblos LXIII: 1–22.

- ——— (1988). "Do Cancioneiro da Ajuda ao Livro das Cantigas do Conde D. Pedro. Análise do acrescento à secção das cantigas de amigo de O", Revista de História das Ideias 10: 691–751.

- ——— (1989). "A Galiza e a cultura trovadoresca peninsular", Revista de História das Ideias 11: 7–36.

- ——— (1993). "A caminho de Galiza. Sobre as primeiras composições em galego-português", in O Cantar dos Trobadores. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia, pp. 249–260 (republished in Oliveira 2001b: 65–78).

- ——— (1994). Depois do Espectáculo Trovadoresco. a estrutura dos cancioneiros peninsulares e as recolhas dos séculos XIII e XIV. Lisboa: Edições Colibri (Colecção: Autores Portugueses).

- ——— (1995). Trobadores e Xograres. Contexto histórico. (tr. Valentín Arias) Vigo: Edicións Xerais de Galicia (Universitaria / Historia crítica da literatura medieval).

- ——— (1997a). "Arqueologia do mecenato trovadoresco em Portugal", in Actas do 2º Congresso Histórico de Guimarães, 319–327 (republished in Oliveira 2001b: 51–62).

- ——— (1997b). "História de uma despossessão. A nobreza e os primeiros textos em galego-português", in Revista de História das Ideias 19: 105–136.

- ——— (1998a). "Le surgissement de la culture troubadouresque dans l'occident de la Péninsule Ibérique (I). Compositeurs et cours", in (Anton Touber, ed.) Le Rayonnement des Troubadours, Amsterdam, pp. 85–95 (Internationale Forschungen zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft) (Port. version in Oliveira 2001b: 141–170).

- ——— (1998b). "Galicia trobadoresca", in Anuario de Estudios Literarios Galegos 1998: 207–229 (Port. Version in Oliveira 2001b: 97–110).

- ——— (2001a). Aventures i Desventures del Joglar Gallegoportouguès (tr. Jordi Cerdà). Barcelona: Columna (La Flor Inversa, 6).

- ——— (2001b). O Trovador galego-português e o seu mundo. Lisboa: Notícias Editorial (Colecção Poliedro da História).

For Galician-Portuguese prose, the reader might begin with:

- Cintra, Luís F. Lindley. (1951–1990). Crónica Geral de Espanha de 1344. Edição crítica do texto português pelo –. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional-Casa de Moeda (vol. I 1951 [1952; reprint 1983]; vol II 1954 [republished 1984]; vol. III 1961 [republished 1984], vol. IV 1990) (Academia Portuguesa da História. Fontes Narrativas da História Portuguesa).

- Lorenzo, Ramón. (1977). La traduccion gallego de la Cronica General y de la Cronica de Castilla. Edición crítica anotada, con introduccion, índice onomástico e glosario. 2 vols. Orense: Instituto de Estudios Orensanos 'Padre Feijoo'.

There is no up-to-date historical grammar of medieval Galician-Portuguese. But see:

- Huber, Joseph. (1933). Altportugiesisches Elementarbuch. Heidelberg: Carl Winter (Sammlung romanischer Elementar- und Händbucher, I, 8) (Port tr. [by Maria Manuela Gouveia Delille] Gramática do Português Antigo. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1986).

A recent work centered on Galician containing information on medieval Galician-Portuguese is:

- Ferreiro, Manuel. (2001). Gramática Histórica Galega, 2 vols. [2nd ed.], Santiago de Compostela: Laiovento.

- An old reference work centered on Portuguese is:

- Williams, Edwin B. (1962). From Latin to Portuguese. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1st ed. Philadelphia, 1938).

Latin Lexica:

- Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus. Lexique Latin Médiévale-Francais/Anglais. A Medieval Latin-French/English Dictionary. composuit J. F. Niermeyer, perficiendum curavit C. van de Kieft. Abbreviationes et index fontium composuit C. van de Kieft, adiuvante G. S. M. M. Lake-Schoonebeek. Leiden – New York – Köln: E. J. Brill 1993 (1st ed. 1976).

- Oxford Latin Dictionary. ed. P. G. W. Glare. Oxford: Clarendon Press 1983.

Historical and Comparative Grammar of Latin:

- Weiss, Michael. (2009). Outline of the Historical and Comparative Grammar of Latin. Ann Arbor, MI: Beechstave Press.

On the early documents cited from the late 12th century, please see Ivo Castro, Introdução à História do Português. Geografia da Língua. Português Antigo. (Lisbon: Colibri, 2004), pp. 121–125 (with references).

External links

- Latin – Portuguese document, a.D. 1008

- Ponte nas ondas

- Pergaminhos: colecção da Casa de Sarmento

- Galician-Portuguese Intangible Heritage

- Galician-Portuguese Intangible Heritage -Videos