Old National Library Building

The Old National Library Building was a historical building at Stamford Road in the Museum Planning Area of Singapore. Originally completed in 1960, it housed the National Library and was a national icon for many Singaporeans. Despite a huge groundswell of public dissent, the library was closed on 31 March 2004, and was demolished to make way for the construction of the Fort Canning Tunnel to ease road traffic to the city. The controversy surrounding the building's demise has been credited for sparking greater awareness of local cultural roots and an unprecedented wave in favour of heritage conservation among Singaporeans.

History

The Singapore National Library traces its roots to Sir Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, who in 1823 started a small private collection of books housed in the Raffles Institution. This was known as Raffles Library, and access to the collection was limited to the British and privileged class.[1] Dr. Robert Morrison, an eminent missionary and educator became the first librarian from 1823 to 1845. He was mainly responsible for establishing the plans with Raffles and soliciting book donations for the Library.[2]

World War II

The Raffles Library was converted into a Regimental Aid Station by the British and Australian army during the Japanese invasion in February 1942. The Library building suffered damages on its northwestern wall and rooftop during the invasion. After the British surrender of Singapore on 15 February 1942, the Library was taken over by the Japanese and renamed the Shonan Library (昭南図書館 Shōnan Toshokan) during the Japanese Occupation. On 29 April 1942, it reopened to the public on the occasion of the birthday of the Emperor of Japan, Hirohito.[3] Shōnan Toshokan was headed by Marquis Yoshichika Tokugawa as its President, a relative of the Japanese Emperor.[4]

On 18 February 1942, E.J.H. Corner, the assistant Director of Gardens in the Straits Settlement, with the support of Sir Shenton Thomas, met a group of Japanese scientists and nobles with the intention of protecting the invaluable collections of the Library and museum. He was later enlisted by Professor Hidezo Tanakadate to assist in re-establishing the library and museum. To increase its collection, abandoned books and journals were collected from all across the states of Malaya and deposited at the Library.[4]

The Library was patronised mainly by the Japanese and captured European staff from the Department of Information, who created propaganda for the Japanese invasion of India and Australia. More than 13,000 volumes were also circulated to civil internees at the Maxwell Road Customs House and prisoners-of-war at Changi Prison. Among these volumes were prayer books, hymnals, music sheets and children's books.[4]

Post-war

After the Japanese surrender in September 1945, Lieutenant-Colonel G. Archey of the British Military Administration took over Directorship of the Library and museum on 6 September. The Library only suffered minimal losses and damages during the three and a half years of Japanese Occupation, as the Japanese preserved the Library well due to its respected reputation in academia. Compared to other libraries in Malaya which lost nearly half of their collections, only some 500 reference books were looted according to a stocktake done after the war.[4]

In the 1950s, public demand mounted for a free public library to meet the needs of all levels of society. Lee Kong Chian, a renowned Chinese community leader and philanthropist, offered S$350,000 in 1953 towards the founding of the first free public library in Singapore on condition that vernacular languages were promoted and encouraged in the public arena. The British government accepted the offer without hesitation and began demolishing the old St Andrew's Chapel and the British Council Hall sited at the foot of Fort Canning Hill along Stamford Road to make way for the new library.[5] The chosen site was situated among many civic and educational institutions on or around Fort Canning Hill and the nearby Bras Basah area. Lee later laid the foundation stone that reads:

| “ | On 15th Aug 1953, this stone was laid by Mr. Lee Kong Chian whose generous contribution initiated this project.[6] | ” |

50 years later, on 15 September 2003, his son Dr. Lee Seng Gee repeated history when the Lee Foundation he chaired gave S$60 million to the National Library Board, the largest single corporate donation ever in Singapore.[7] In July 2005, the new National Reference Library at Victoria Street was named Lee Kong Chian Library in his father's honour.

New building

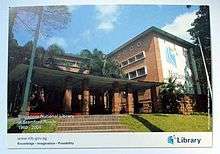

Designed and built by the Public Works Department, the new red-bricked building was officially opened and christened as the National Library on 12 November 1960 by the President of Singapore, Yusof bin Ishak.[3] The architecture was said to reflect the red-brick epoch of British architecture in the 1950s. Hedwig Anuar was appointed the first Singaporean Director of the National Library in April 1960 and served until June 1961.[8] Aside from its extensive English collection, the library also made Chinese, Malay and Tamil books available for loan. Occupying a total floor area of 10,242 square metres, the library included reading sections for adults and children, a microfilm unit and a lecture hall.

To cultivate reading habits among the young, the Library initiated many activities such as story-telling sessions for children and talks for teenagers, conducted by the staff or members of the public. Among adults, the Library also promoted books written by local writers, publishing a bibliography of their writings and encouraging Singaporeans to read local literature in all languages. Such activities are still being carried out by the National Library Board to the present day.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Library became a popular destination for studying and hanging out for young people from well-known neighbouring schools such as Raffles Institution, Raffles Girls' School, St Joseph's Institution and Tao Nan School that had their early beginnings in this area. The landmark Balustrade or front porch and steps leading up to the Library became an intimate public space where one could sit and read, wait, chat or simply watch the world go by.[9]

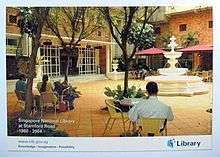

The Courtyard Cafe and The Fountain located within the Library also became an institution, well-patronised by library users, office workers and the local arts community from The Substation. As such, many fond memories were created for those who visited the compounds of the Library. At the same time, the pressure of urban redevelopment in the city was building up, resulting in demolishing of old city fabric that would threaten the Library building's fate and its sentimental memories in the ensuing years.

Civic and Cultural District Master Plan

A Civic and Cultural District Master Plan Exhibition was held in April 1988 by the Ministry of National Development (MND) to garner public feedback to develop the Central area into a historical, cultural and retail zone. The 1988 Master Plan was aimed to revitalise Singapore's civic and cultural hub, citing the location of key cultural institutions such as the Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall, the National Museum, as well as the National Library within the District.[10]

On 28 May, the MND Minister, S. Dhanabalan chaired a dialogue attended predominantly by invited professionals such as planners, architects and property consultants to review the Master Plan exhibited a month earlier. During the professional dialogue, the Urban Redevelopment Authority's (URA) many microplanning proposals were reviewed, including the proposed demolition of the National Library to create a "clear view of Fort Canning Hill from Bras Basah Park". No conclusive statement on the building's fate was made in the press report or in URA's publication, Skyline Vol. 35/88 (Jul/Aug 1988).[11]

New national library

On 23 March 1989, the MND revealed plans in Parliament to build a new National Library and four new branches in Yishun, Tampines, Hougang and Woodlands.[12] This announcement generated extensive discussion in the ensuing months on the potential of a new National Library. On 17 March 1990, the Ministry of Community Development confirmed in Parliament that the new National Library would be sited at the former Raffles Girls' School site in Queen Street. A library consultant was appointed the following month to advise on the planning of the new building.[13]

Revision in plan

The 1992 Civic District Master Plan public exhibition was held from 22–26 February by the URA. An important revision was the mentioning of the one-way Fort Canning Tunnel, entering the hill at the existing National Library and emerging at Penang Road to be built by the year 2000. The URA explained that the 380m long tunnel would help smoothen the major traffic intersection in front of Cathay Building and direct heavy traffic away from the Marina to Orchard areas, thus giving the museum precinct a peaceful and quiet ambience.

Work on the tunnel was expected to start after the National Library is relocated to Victoria Street by 1996. In the extensive press reports in 1992, neither the demolition of the National Library building nor the reasons for changing the site of the new National Library to Victoria Street were given.[14]

In the subsequent 1997 Master Plan for the area, plans for the Fort Canning Tunnel remained unchanged and it was not explicitly stated in the report that the National Library building would be demolished.[15] In April 1997, the Library was closed for a S$2.6 million upgrading and renovation programme to meet the needs of the IT age. It was planned to reopen on 1 Oct, with its facilities upgraded, with new computers, and its collection updated with 80,000 volumes added.[16] Actual renovations took nine months and the library was officially reopened on 16 January 1998.[17]

'National Library to go'

On 8 December 1998, a letter by Kelvin Wang to the Straits Times Forum page triggered a string of events that would bring the normally passive Singaporeans to display rare sparks of civic activism. Wang brought to the public attention that there was a possibility that the National Library would be demolished, after a recent announcement by the newly formed Singapore Management University (SMU) that its new city campus would be sited in the Bras Basah area including the National Library's present site.[18] Wang wrote:

Bras Basah has lost too many unique buildings already, and we should not lose the National Library because it would mean that Singaporeans will not only lose another part of their history, but also a part of what forms their collective memory, which helps make Singapore "home".[19]

In response, the SMU assured the public that they could play a part in deciding the fate of the red-bricked building housing the National Library, as it had not decided what to do with the building.[20] On 13 March 1999, SMU organised a public symposium at the Singapore Art Museum (former St Joseph's Institution) to gather feedback for its campus masterplan. Overwhelming turnout and passionate debate amongst the audience marked this highly publicised event, which lasted over 4 hours. This was the first occasion where URA made public their definitive decision to demolish the National Library building as "it was not of great architectural merit and should not be conserved."[21]

Public dissent

From March to April 1999, there arose a huge groundswell of public dissent in the media over the National Library building's fate, as well as the drastic physical alterations of its environs. A number of featured columns by journalists touched on gradually disappearing heritage landmarks, as well as shared memories of Singaporeans.[22]

On 24 January 2000, after SMU chaired a technical workshop to obtain feedback on three alternative proposals, a well-known architect named Tay Kheng Soon held a press conference at The Substation to unveil his unofficial SMU masterplan. URA was invited to the presentation but did not show up. His proposal entailed re-routing the tunnel to save the National Library building. A week later, Tay wrote to the Prime Minister's Office regarding his proposal which was referred to the MND.[23] Many members of the public wrote in publicly either in support of Tay's plans or argue for heritage conservation in general. A few articles and letters highlighted that the adamant official response to public dissent ran counter to the spirit of the Government's S21 Vision, which expressed a desire to foster civic participation and active citizenry.[24]

On 7 March 2000, the Minister for National Development, Mah Bow Tan, announced in Parliament that the National Library building would have to go. According to Mah, the authorities had assessed Tay's plans but concluded that the URA's plan was a better proposal for preserving the Civic District's ambience and being more people-friendly.[25] With no choice, the public and activists accepted the final decision to demolish their beloved Library and the debates slowly frizzled off.

Aftermath

The old National Library was eventually torn down in 2005. Today, all that remains of the building at its original site are two red-bricked entrance pillars standing near the Fort Canning Tunnel. The controversy surrounding the building's demise has been credited for sparking greater awareness of local cultural roots and an unprecedented wave in favour of heritage conservation among Singaporeans.[26][27]

The new National Library at Victoria Street was completed on July 2005. In memory of the old National Library building, about 5,000 red bricks were salvaged from the old Library and used to construct a commemorative wall in a bamboo garden located within the new building.

See also

References

- ↑ Kwok, "Chronologue: 1823—1960", pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Seet, "The Early Years: 1823—1845", p. 14.

- 1 2 Seet, "The Japanese Occupation and Postwar Years", p. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 Heirwin Mohd Nasir (7 October 2002). "Raffles Library and Museum during the Japanese Occupation". Singapore Infopedia. Retrieved 22 June 2007.

- ↑ Kwok, "Chronologue: 1823—1960", pp. 8–16.

- ↑ Seet, "A Free Public Library", p. 21.

- ↑ Seet, "Like Father, Like Son", p. 146.

- ↑ Seet, "Milestones", p. 160.

- ↑ Kwok, "Chronologue: 1960—1987", pp. 24–26.

- ↑ Jennifer Koh (12 March 1998). "Civic centre plan unveiled". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Agnes Wee (29 May 1998). "Professionals share views on Heart of Singapore". The Straits Times.

- ↑ "Plan to build new National Library". The Straits Times. 23 March 1989.

- ↑ "New National Library at ex-RGS site". The Straits Times. 17 March 1990.

- ↑ Julia Goh (21 February 1992). "A Piece of Peace in the City". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Kwok, "Chronologue: 1987—1997", p. 56.

- ↑ Claudette Peralta (12 March 1997). "National Library's 2.6m facelift". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Ong Sor Fern (16 January 1998). "Welcome to 60,000 new books, 38 PCs". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Sandra Davie (6 December 1998). "New campus at Bras Basah". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Kelvin Wang (8 December 1998). "Let's not lose National Library". The Straits Times.

- ↑ "Public will have a say in building's fate". The Straits Times. 9 December 1998.

- ↑ M. Nirmala (14 March 1999). "National Library to go". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Ho Weng Hin et el (16 March 1999). "Heed the people's call, conserve 'built' heritage". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Lydia Lim (25 January 2000). "New plan for Bras Basah Park offered". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Cheang Kum Hon (12 February 2000). "S21 Vision at stake with library issue". The Straits Times.

- ↑ Lydia Lim (7 March 2000). "National Library building to go". The Straits Times.

- ↑ "How important are those five minutes?". Siew Kum Hong, Nominated Member of Parliament. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ↑ "Was the demolishing of the old National Library a well-thought decision?". The Online Citizen. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

Bibliography

- Kwok Kian Woon et al. (2000). Memories and the National Library: Between forgetting and remembering. Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, pp. 1–213. ISBN 981-04-2896-0.

- Dr. K.K. Seet (2005). Knowledge, Inspiration, Possibility – Singapore Transformative Library. Singapore: SNP International Publishing Pte Ltd. ISBN 981-248-107-9.

- National Library Board (2004). Moments in Time – Memories of the National Library. , Singapore: National Library Board. ISBN 9810516851