Seppuku

Seppuku (切腹, "cutting [the] abdomen/belly", formal on reading of original Kanji), sometimes metathesized as harakiri (腹切り, "abdomen/belly cutting") which is a native Japanese kun reading,[1] is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. It was originally reserved for samurai.[2] A samurai practice, seppuku was used either voluntarily by samurai to die with honor rather than fall into the hands of their enemies (and likely suffer torture) or as a form of capital punishment for samurai who had committed serious offenses, or performed because they had brought shame to themselves. The ceremonial disembowelment, which is usually part of a more elaborate ritual and performed in front of spectators, consists of plunging a short blade, traditionally a tantō, into the abdomen and drawing the blade from left to right, slicing the abdomen open.[3] If the cut, done with a movement, is done deep enough, it can cut the descending aorta, inducing a massive blood loss inside the abdomen, with a very fast death.

Etymology

The term "seppuku" is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots setsu 切 ("to cut", from Middle Chinese tset) and puku 腹 ("belly", from MC pjuwk). It is also known as harakiri (腹切り, "cutting the belly"),[4] a term more widely familiar outside Japan, and which is written with the same kanji as seppuku, but in reverse order with an okurigana. In Japanese, the more formal seppuku, a Chinese on'yomi reading, is typically used in writing, while harakiri, a native kun'yomi reading, is used in speech. Ross notes,

It is commonly pointed out that hara-kiri is a vulgarism, but this is a misunderstanding. Hara-kiri is a Japanese reading or Kun-yomi of the characters; as it became customary to prefer Chinese readings in official announcements, only the term seppuku was ever used in writing. So hara-kiri is a spoken term, but only to commoners and seppuku a written term, but spoken amongst higher classes for the same act.[5]

The practice of committing seppuku at the death of one's master, known as oibara (追腹 or 追い腹, the kun'yomi or Japanese reading) or tsuifuku (追腹, the on'yomi or Chinese reading), follows a similar ritual.

The word jigai (自害) means "suicide" in Japanese. The modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[6] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[7] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese.[8] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[9]

Overview

The first recorded act of seppuku was performed by Minamoto no Yorimasa during the Battle of Uji in the year 1180.[10] Seppuku was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands, and to attenuate shame and avoid possible torture. Samurai could also be ordered by their daimyō (feudal lords) to carry out seppuku. Later, disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to carry out seppuku rather than be executed in the normal manner. The most common form of seppuku for men was composed of the cutting of the abdomen, and when the samurai was finished, he stretched out his neck for an assistant to sever his spinal cord by cutting halfway into the neck. Since the main point of the act was to restore or protect one's honor as a warrior, the condemned should not be decapitated completely; instead left with a small part of the throat or neck still attached. This way the head could, both metaphorically and literally, rest in its owner's hands. Those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to carry out seppuku. Samurai generally could carry out the act only with permission.

Sometimes a daimyō was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement. This weakened the defeated clan so that resistance effectively ceased. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used an enemy's suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of daimyōs. When the Hōjō were defeated at Odawara in 1590, Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired daimyō Hōjō Ujimasa, and the exile of his son Ujinao; with this act of suicide, the most powerful daimyō family in eastern Japan was put to an end.

Ritual

Until this practice became more standardized during the 17th century, the ritual of seppuku was less formalized. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the seppuku of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a kaishakunin (idiomatically, his "second") had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. Seppuku's defining characteristic was plunging either the Tachi (longsword), Wakizashi (shortsword) or Tanto (knife) into the gut and slicing the abdomen horizontally. In the absence of a kaishakunin, the samurai would then remove the blade, and stab himself in the throat, or fall (from a standing position) with the blade positioned against his heart.

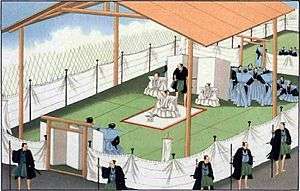

During the Edo Period (1600–1867), carrying out seppuku came to involve a detailed ritual. This was usually performed in front of spectators if it was a planned seppuku, not one performed on a battlefield. A samurai was bathed, dressed in white robes, and served his favorite foods for a last meal. When he had finished, the knife and cloth were placed on another sanbo and given to the warrior. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special clothes, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. He would be dressed in the shini-shōzoku, a completely white kimono worn for death.[11]

With his selected kaishakunin standing by, he would open his kimono (robe), take up his tantō (knife) or wakizashi (short sword)—which the samurai held by the blade with a portion of cloth wrapped around so that it would not cut his hand and cause him to lose his grip—and plunge it into his abdomen, making a left-to-right cut. Prior to this, he would probably consume an important ceremonial drink of sake. He would also give his attendant a cup meant for sake.[12] The kaishakunin would then perform kaishaku, a cut in which the warrior was decapitated. The maneuver should be done in the manners of dakikubi (lit. "embraced head"), in which way a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body, so that it can be hung in front as if embraced. Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was a skilled swordsman. The principal and the kaishakunin agreed in advance when the latter was to make his cut. Usually dakikubi would occur as soon as the dagger was plunged into the abdomen. The process became so highly ritualised that as soon as the samurai reached for his blade the kaishakunin would strike. Eventually even the blade became unnecessary and the samurai could reach for something symbolic like a fan and this would trigger the killing stroke from his second. The fan was likely used when the samurai was too old to use the blade or in situations where it was too dangerous to give him a weapon.[13]

This elaborate ritual evolved after seppuku had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and became a para-judicial institution.

The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honourably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote:

From ages past it has been considered an ill-omen by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. Further, if one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace.In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials.

A specialized form of seppuku in feudal times was known as kanshi (諫死, "remonstration death/death of understanding"), in which a retainer would commit suicide in protest of a lord's decision. The retainer would make one deep, horizontal cut into his abdomen, then quickly bandage the wound. After this, the person would then appear before his lord, give a speech in which he announced the protest of the lord's action, then reveal his mortal wound. This is not to be confused with funshi (憤死, indignation death), which is any suicide made to state dissatisfaction or protest. A fictional variation of kanshi was the act of kagebara (陰腹, "shadow belly") in Japanese theater, in which the protagonist, at the end of the play, would announce to the audience that he had committed an act similar to kanshi, a predetermined slash to the belly followed by a tight field dressing, and then perish, bringing about a dramatic end.

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of seppuku known as jūmonji giri (十文字切り, "cross-shaped cut"), in which there is no kaishakunin to put a quick end to the samurai's suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut on the belly. A samurai performing jumonji giri was expected to bear his suffering quietly until he bleeds to death, passing away with his hands over his face.[14]

Female ritual suicide

Female ritual suicide, known as Jigai, was practiced by the wives of samurai who have committed seppuku or brought dishonor.[15][16]

Some women belonging to samurai families committed suicide by cutting the arteries of the neck with one stroke, using a knife such as a tantō or kaiken. The main purpose was to achieve a quick and certain death in order to avoid capture. Women were carefully taught jigai as children. Before committing suicide, a woman would often tie her knees together so her body would be found in a dignified pose, despite the convulsions of death. Jigai, however, does not refer exclusively to this particular mode of suicide. Jigai was often done to preserve one's honor if a military defeat was imminent, so as to prevent rape. Invading armies would often enter homes to find the lady of the house seated alone, facing away from the door. On approaching her, they would find that she had ended her life long before they reached her.

History

Stephen R. Turnbull provides extensive evidence for the practice of female ritual suicide, notably of samurai wives, in pre-modern Japan. One of the largest mass suicides was the 25 April 1185 final defeat of Taira Tomomori establishing Minamoto power.[15] The wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, is a notable example of a wife following by suicide the seppuku of a samurai husband.[17] A large number of honor suicides marked the defeat of the Aizu clan in the Boshin War of 1869, leading into the Meiji era. For example, in the family of Saigō Tanomo, who survived, a total of twenty-two female honor suicides are recorded among one extended family.[18]

Religious and social context

Voluntary death by drowning was a common form of ritual or honour suicide. The religious context of thirty-three Jōdo Shinshū adherents at the funeral of Abbot Jitsunyo in 1525 was faith in Amida and belief in afterlife in the Pure Land, but male seppuku did not have a specifically religious context.[19] By way of contrast, the religious beliefs of Hosokawa Gracia, the Christian wife of daimyō Hosokawa Yusai, prevented her from committing suicide.[20]

Terminology

The word jigai (自害) means "suicide" in Japanese. The usual modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). Related words include jiketsu (自決), jijin (自尽) and jijin (自刃).[21] In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[6] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[7] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese and Hearn seen through Japanese eyes.[8] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[9] Mostow's context is analysis of Giacomo Puccini's Madame Butterfly and the original Cio-Cio San story by John Luther Long. Though both Long's story and Puccini's opera predate Hearn's use of the term jigai, the term has been used in relation to western japonisme which is the influence of Japanese culture on the western arts.[22]

As capital punishment

While the voluntary seppuku described above is the best known form, in practice the most common form of seppuku was obligatory seppuku, used as a form of capital punishment for disgraced samurai, especially for those who committed a serious offence such as rape, robbery, corruption, unprovoked murder or treason. The samurai were generally told of their offense in full and given a set time to commit seppuku, usually before sunset on a given day. On occasion, if the sentenced individuals were uncooperative or outright refused to end their own lives, it was not unheard of for them to be restrained and the seppuku carried out by an executioner, or for the actual execution to be carried out instead by decapitation while retaining only the trappings of seppuku; even the short sword laid out in front of the offender could be replaced with a fan. Unlike voluntary seppuku, seppuku carried out as capital punishment did not necessarily absolve, or pardon, the offender's family of the crime. Depending on the severity of the crime, all or part of the property of the condemned could be confiscated, and the family would be punished by being stripped of rank, sold into long-term servitude, or execution.

Seppuku was considered the most honorable capital punishment apportioned to Samurai. Zanshu (斬首) and Sarashikubi (晒し首), decapitation followed by a display of the head, was considered harsher, and reserved for samurai who committed greater crimes. The harshest punishments, usually involving death by torturous methods like Kamayude (釜茹で), death by boiling, were reserved for commoner offenders.

European witness

The first recorded time a European saw formal seppuku was the "Sakai Incident" of 1868. On February 15, eleven French sailors of the Dupleix entered a Japanese town called Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and the sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, financial compensation was paid and those responsible were sentenced to death. The French captain was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the violent act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, as a result of which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatised in a famous short story, Sakai Jiken, by Mori Ōgai.

In the 1860s, the British Ambassador to Japan, Algernon Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), lived within sight of Sengaku-ji where the Forty-seven Ronin are buried. In his book Tales of Old Japan, he describes a man who had come to the graves to kill himself:

I will add one anecdote to show the sanctity which is attached to the graves of the Forty-seven. In the month of September 1868, a certain man came to pray before the grave of Oishi Chikara. Having finished his prayers, he deliberately performed hara-kiri, and, the belly wound not being mortal, dispatched himself by cutting his throat. Upon his person were found papers setting forth that, being a Ronin and without means of earning a living, he had petitioned to be allowed to enter the clan of the Prince of Choshiu, which he looked upon as the noblest clan in the realm; his petition having been refused, nothing remained for him but to die, for to be a Ronin was hateful to him, and he would serve no other master than the Prince of Choshiu: what more fitting place could he find in which to put an end to his life than the graveyard of these Braves? This happened at about two hundred yards' distance from my house, and when I saw the spot an hour or two later, the ground was all bespattered with blood, and disturbed by the death-struggles of the man.

Mitford also describes his friend's eyewitness account of a seppuku:

There are many stories on record of extraordinary heroism being displayed in the harakiri. The case of a young fellow, only twenty years old, of the Choshiu clan, which was told me the other day by an eye-witness, deserves mention as a marvellous instance of determination. Not content with giving himself the one necessary cut, he slashed himself thrice horizontally and twice vertically. Then he stabbed himself in the throat until the dirk protruded on the other side, with its sharp edge to the front; setting his teeth in one supreme effort, he drove the knife forward with both hands through his throat, and fell dead.

During the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa Shogun's aide committed seppuku:

One more story and I have done. During the revolution, when the Taikun (Supreme Commander), beaten on every side, fled ignominiously to Yedo, he is said to have determined to fight no more, but to yield everything. A member of his second council went to him and said, "Sir, the only way for you now to retrieve the honour of the family of Tokugawa is to disembowel yourself; and to prove to you that I am sincere and disinterested in what I say, I am here ready to disembowel myself with you." The Taikun flew into a great rage, saying that he would listen to no such nonsense, and left the room. His faithful retainer, to prove his honesty, retired to another part of the castle, and solemnly performed the harakiri.

In his book Tales of Old Japan, Mitford describes witnessing a hara-kiri:[23]

"As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the harakiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburo, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hyōgo in the month of February 1868,—an attack to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and the Hatamoto. Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveler's fable.The ceremony, which was ordered by the Mikado (Emperor) himself, took place at 10:30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all. After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows:

I, and I alone, unwarrantably gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kobe, and again as they tried to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and I beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible.

The kaishaku made a low bow, wiped his sword with a piece of rice paper which he had ready for the purpose, and retired from the raised floor; and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution. The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places, and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence of death upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the temple. The ceremony, to which the place and the hour gave an additional solemnity, was characterized throughout by that extreme dignity and punctiliousness which are the distinctive marks of the proceedings of Japanese gentlemen of rank; and it is important to note this fact, because it carries with it the conviction that the dead man was indeed the officer who had committed the crime, and no substitute. While profoundly impressed by the terrible scene it was impossible at the same time not to be filled with admiration of the firm and manly bearing of the sufferer, and of the nerve with which the kaishaku performed his last duty to his master."

Seppuku in modern Japan

Seppuku as judicial punishment was abolished in 1873, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, but voluntary seppuku did not completely die out. Dozens of people are known to have committed seppuku since then, including some military men who committed suicide in 1895 as a protest against the return of a conquered territory to China; by General Nogi and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912; and by numerous soldiers and civilians who chose to die rather than surrender at the end of World War II. This behavior had been widely praised by propaganda, which made a soldier captured in the Shanghai Incident (1932) return to the site of his capture to commit seppuku.[24]

In 1970, author Yukio Mishima and one of his followers committed public seppuku at the Japan Self-Defense Forces headquarters after an unsuccessful attempt to incite the armed forces to stage a coup d'état. Mishima committed seppuku in the office of General Kanetoshi Mashita. His second, a 25-year-old named Masakatsu Morita, tried three times to ritually behead Mishima but failed; his head was finally severed by Hiroyasu Koga. Morita then attempted to commit seppuku himself. Although his own cuts were too shallow to be fatal, he gave the signal and he too was beheaded by Koga.[25]

Notable cases

This list of notable seppuku cases is in chronological order.

In popular cultureThe expected honor-suicide of the samurai wife is frequently referenced in Japanese literature and film, such as in Taiko by Eiji Yoshikawa, Humanity and Paper Balloons,[26] and Rashomon.[27] Seppuku is also referenced and described multiples times in the 1975 James Clavell novel, Shōgun; its subsequent 1980 television adaptation brought the term and the concept to mainstream Western attention. See also

ReferencesNotes

Further reading

External links

|