American pika

| American pika[1] | |

|---|---|

| | |

| An American pika feeding on grass in the Canadian Rocky Mountains | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Ochotonidae |

| Genus: | Ochotona |

| Species: | O. princeps |

| Binomial name | |

| Ochotona princeps (Richardson, 1828) | |

| Subspecies[3] | |

|

O. princeps princeps | |

| |

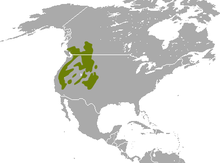

| American pika range | |

The American pika (Ochotona princeps), a diurnal species of pika, is found in the mountains of western North America, usually in boulder fields at or above the tree line. They are herbivorous, smaller relatives of rabbits and hares.[4]

Description

The American pika, known in the 19th century as the "little chief hare",[5] has a small, round, ovate body. Their body length ranges from 162 to 216 mm (6.4 to 8.5 in). Their hind feet range from 25 to 35 mm (1–1½ in).[6] They usually weigh about 170 g (6.0 oz).[7] Body size can vary among populations. In populations with sexual dimorphism, males are slightly larger than females.[8]

The American pika is intermediate in size among pikas. The hind legs of the pika do not seem to be much longer than its front legs and its hind feet are relatively short when compared to most other lagomorphs.[8] It has densely furred soles on its feet except for black pads at the ends of the toes.[8] The ears are moderately large and suborbicular and are hairy on both surfaces, normally dark with white margins. The pika's "buried" tail is longer relative to body size compared to other lagomorphs.[8] It has a slightly rounded skull with a broad and flat preorbital region. The fur color of the pika is the same for both sexes, but varies by subspecies and season.[8] The dorsal fur of the pika ranges from grayish to cinnamon-brown, often colored with tawny or orchraceous hues, during the summer. During winter, the fur becomes grayer and longer.[8] The dense underfur is usually slate-gray or lead-colored. It also has whitish ventral fur. Males are called bucks and females are called does like rabbits.

Distribution and habitat

The American pika can be found throughout the mountains of western North America, from central British Columbia and Alberta in Canada to the US states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California and New Mexico.[7]

Pikas inhabit talus fields that are fringed by suitable vegetation on alpine areas. They also live in piles of broken rock.[8][9] Sometimes, they live in man-made substrate such as mine tailings and piles of scrap lumber. Pikas usually have their den and nest sites below rock around 0.2–1 m in diameter but often sit on larger and more prominent rocks. They generally reside in scree near or above the tree line. Pikas are restricted to cool moist microhabitats on high peaks or watercourses.[9] Intolerant of high diurnal temperatures, in the northern portion of their range they may be found near sea level, but in the south they are rare below 2,500 metres (8,200 ft).[8] Pikas rely on existing spaces in the talus for homes and do not dig burrows. However, they can enlarge their home by digging.[8]

Diet

The American pika is a generalist herbivore. It eats a large variety of green plants, including different kinds of grasses, sedges, thistles and fireweed. Although pikas can meet their water demands from the vegetation they eat, they do drink water if it is available in their environment.[10] Pikas have two different ways of foraging: they directly consume food (feeding) or they cache food in haypiles to use for a food source in the winter (haying).[8] The pika feeds throughout the year while haying is limited to the summer months. Since they do not hibernate, pikas have greater energy demands than other montane mammals. In addition, they also make 13 trips per hour to collect vegetation when haying, up to a little over 100 trips per day.[11] It seems that the timing of haying correlates to the amount of precipitation from the previous winter.[12] Pikas start and then quit haying earlier in years following little snow and early spring. In areas at lower elevations, haying begins before the snow has melted at high altitudes; while at higher elevations, haying continues after it ends in lower elevations.[12]

When haying, pikas harvest plants in a deliberate sequence, corresponding to their seasonal phenology.[8] They seem to assess the nutritional value of available food and harvest accordingly. Pikas select plants that have the higher caloric, protein, lipid and water content.[8] Forbs and tall grass tend to be hayed more than eaten directly. Haypiles tend to be stored under the talus near the talus-meadow interface although they may be constructed on the talus surface. Males generally store more vegetation than females and adults usually store more than juveniles.[8] Pikas deposit two kinds of fecal droppings: Hard brown round pellets and caecal pellets that are soft black shiny strings that form in the caecum.[8] Caecal pellets have more energy value than stored plant food and the pika may consume them directly or store them for later.[8]

Life history

American pikas are diurnal. The total area of land which an American pika uses is known as a home range. Approximately 55% of its home range is territory which the pika defends against intruders. Territory size can vary from 410–709 m² and is dependent on configuration, distance to vegetation and quality of vegetation.[8] The home ranges of pika may overlap with the distances of the home ranges of a mating pair being shorter than that of the nearest neighbors of the same sex.[8] Spatial distances between adults of a pair is greatest during early and mid summer and reduces during late summer and early autumn. Pikas defend their territories with aggression. Actual aggressive encounters are rare and usually occur between members of the same sex and those unfamiliar with each other. A pika may intrude on another’s territory but usually when the resident is not active. During haying, territorial behavior increases.[10]

Adult pikas of the opposite sex with territories adjacent form mated pairs. When there is more than one male available, females will exhibit mate choice.[8] Pikas are reflex ovulators, that is ovulation only occurs after copulation, and they are also seasonally polyestrous. A female has two litters per year and these litters average three young each. Breeding takes place one month before the snow melts and gestation lasts approximately 30 days. Parturition occurs as early as March in lower elevations but occurs from April to June at higher elevations. Lactation significantly reduces a female's fat reserves and they only nurse the second litter if the first does not survive, despite exhibiting postpartum estrus.[8] Pikas are born slightly altricial, being blind, slightly haired, and having fully erupted teeth. They weigh between 10 and 12 grams at birth. At around nine days, they are able to open their eyes.[8] Mothers forage most of the day and return to the nest once every two hours to nurse the young. Young become independent after four weeks, around the same time they are weaned.[8] Young may remain in their natal or an adjoining home range. When in their home range, young occupy areas away from their relatives as much as possible. Dispersal appears to be caused by competition for territories.[13]

Pikas are vocal, using both calls and songs to communicate among themselves. A call is used to warn when a predator is lurking nearby, and a song is used during the breeding season (males only), and during autumn (both males and females).[7] Predators of the pika include eagles, hawks, coyotes, bobcats, foxes, and weasels.

Taxonomy

The American Pika was described in the scientific literature by John Richardson in Fauna Boreali-Americana in 1828. The original scientific name was Lepus (Lagomys) princeps.[14]

_Princeps).jpg)

Conservation and decline

As they live in the high and cooler mountain regions, they are very sensitive to high temperatures, and are considered to be one of the best early warning systems for detecting global warming in the western United States.[15] Temperature increases are suspected to be one cause of American pikas moving higher in elevation[16] in an attempt to find suitable habitat, as well as cooler temperatures. American pikas, however, cannot easily migrate in response to climate change, as their habitat is currently restricted to small, disconnected habitat "islands" in numerous mountain ranges.[17] Pikas can die in six hours when exposed to temperatures above 25.5 °C (77.9 °F) if individuals cannot find refuge from heat. In warmer environments, such as during midday sun and at lower elevation limits, pikas typically become inactive and withdraw into cooler talus openings.[12] Because of behavioral adaptation, American pikas also persist in the hot climates of Craters of the Moon and Lava Beds National Monuments (Idaho and California, respectively). Average and extreme maximum surface temperatures in August at these sites are 32 and 38 °C (90 and 100 °F), respectively.[18]

Recent studies suggest some populations are declining due to various factors, most notably global warming.[16] A 2003 study, published in the Journal of Mammalogy, showed nine of 25 sampled populations of American pika had disappeared in the Great Basin, leading biologists to conduct further investigations to determine if the species as a whole is vulnerable.[19]

In 2010, the US government considered, then decided not to add the American pika under the US Endangered Species Act;[20] in the IUCN Red List it is still considered a Species of Least Concern.[2]

The Pikas in Peril Project,[21] funded through the National Park Service Climate Change Response Program, began data collection in May 2010. A large team of academic researchers and National Park Service staff are working together to address questions regarding the vulnerability of the American pika to future climate change scenarios projected for the western United States.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ochotona princeps. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Ochotona princeps |

- ↑ Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Beever, E.A. & Smith, A.T. (2011). "Ochotona princeps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 18 January 2012. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- ↑ Hafner, David J.; Smith, Andrew T. (April 2010). "Revision of the subspecies of the American pika, Ochotona princeps". Journal of Mammalogy. 91 (2): 401–417. doi:10.1644/09-MAMM-A-277.1.

- ↑ "Pikas". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 9 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Mearns, B & R. John Kirk Townsend: Collector of Audubon’s Western Birds and Mammals. Page 108. Retrieved from on 2009-10-06.

- ↑ "Ochotona princeps". public.srce.hr. Archived from the original on 2005-03-18. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- 1 2 3 "American Pika". NatureWorks. Archived from the original on 1 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Smith, Andrew T.; Weston, Marla L. (1990-04-26). "Ochotona princeps" (PDF). Mammalian Species. The American Society of Mammalogists. 352: 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504319. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- 1 2 Hafner, D.J. (1993) "North American pika (Ochotona princeps) as a late Quaternary biogeographic indicator species". Quaternary Research, 39:373–380.

- 1 2 Martin, J. W. 1982. Southern pika (Ochotona princeps) biology and ecology: a literature review.

- ↑ Erik A. Beever, Peter F. Brussard and Joel Berger (2003) "Patterns of apparent extirpation among isolated populations of pikas (Ochotona princeps) in the Great Basin", Journal of Mammalogy, 84(1):37–54.

- 1 2 3 AT Smith (1974) "The Distribution and Dispersal of Pikas: Influences of Behavior and Climate". Ecology 55:1368–1376.

- ↑ MM Peacock. 1997. "Determining natal dispersal patterns in a population of North American pikas (Ochotona princeps) using direct mark-resight and indirect genetic methods". Behavioral Ecology 8:340–350

- ↑ Richardson, John (1829). Fauna boreali-americana. London: J. Murray. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Paul (August 21, 2003). "American pika doomed as 'first mammal victim of climate change'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- 1 2 Blakemore, Bill (May 9, 2007). "Route to Extinction Goes up Mountains, Scientists Say". World News with Charles Gibson. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ http://www.worldwildlife.org/species/finder/americanpika/americanpika.html

- ↑ Dept. of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, 12-month Finding on a Petition to List the American Pika as Threatened or Endangered

- ↑ van Noordennen, Pieter (May 9, 2007). "American Pika". GORP. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ↑ Reis, Patrick (2010-02-05). "Obama Admin Denies Endangered Species Listing for American Pika". New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ↑ http://science.nature.nps.gov/im/units/ucbn/monitor/pikas_in_peril.cfm

External links

- View the Pika genome in Ensembl.

- View the ochPri3 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- American pika federal petition