Nut (fruit)

A nut is a fruit composed of an inedible hard shell and a seed, which is generally edible. In general usage, a wide variety of dried seeds are called nuts, but in a botanical context "nut" implies that the shell does not open to release the seed (indehiscent). The translation of "nut" in certain languages frequently requires paraphrases, as the word is ambiguous.

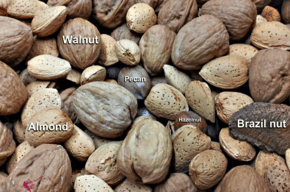

Most seeds come from fruits that naturally free themselves from the shell, unlike nuts such as hazelnuts, chestnuts, and acorns, which have hard shell walls and originate from a compound ovary. The general and original usage of the term is less restrictive, and many nuts (in the culinary sense), such as almonds, pecans, pistachios, walnuts, and Brazil nuts,[1] are not nuts in a botanical sense. Common usage of the term often refers to any hard-walled, edible kernel as a nut.[2]

Botanical definition

A nut in botany is a simple dry fruit in which the ovary wall becomes increasingly hard as it matures, and where the seed remains unattached or free within the ovary wall. Most nuts come from the pistils with inferior ovaries (see flower) and all are indehiscent (not opening at maturity). True nuts are produced, for example, by some plant families of the order Fagales.

- Order Fagales (not all species produce true nuts)

- Family Fagaceae

- Family Betulaceae

A small nut may be called a "nutlet". In botany, this term specifically refers to a pyrena or pyrene, which is a seed covered by a stony layer, such as the kernel of a drupe. Walnuts and hickories (Juglandaceae) have fruits that are difficult to classify. They are considered to be nuts under some definitions, but are also referred to as drupaceous nuts. "Tryma" is a specialized term for hickory fruits.

In common use, a "tree nut" is, as the name implies, any nut coming from a tree. This most often comes up regarding allergies, where some people are allergic specifically to peanuts, others to a wider range of nuts that grow in trees.

Culinary definition and uses

A nut in cuisine is a much less restrictive category than a nut in botany, as the term is applied to many seeds that are not botanically true nuts. Any large, oily kernels found within a shell and used in food are commonly called nuts.

Nuts are an important source of nutrients for both humans and wildlife. Because nuts generally have a high oil content, they are a highly prized food and energy source. A large number of seeds are edible by humans and used in cooking, eaten raw, sprouted, or roasted as a snack food, or pressed for oil that is used in cookery and cosmetics. Nuts (or seeds generally) are also a significant source of nutrition for wildlife. This is particularly true in temperate climates where animals such as jays and squirrels store acorns and other nuts during the autumn to keep from starving during the late autumn, all of winter, and early spring.

Nuts used for food, whether true nut or not, are among the most common food allergens.[3]

Some fruits and seeds that do not meet the botanical definition but are nuts in the culinary sense are:

- Almonds are the edible seeds of drupe fruits — the leathery "flesh" is removed at harvest.

- Brazil nut is the seed from a capsule.

- Candlenut (used for oil) is a seed.

- Cashew is the seed[4] of a drupe fruit with an accessory fruit.

- Chilean hazelnut or Gevuina

- Macadamia is a creamy white kernel of a follicle type fruit.

- Malabar chestnut

- Pecan is the seed of a drupe fruit

- Mongongo

- Peanut is a seed and from a legume type fruit (of the family Fabaceae).

- Pine nut is the seed of several species of pine (coniferous trees).

- Pistachio is the partly dehiscent seed of a thin-shelled drupe.

- Walnut (Juglans) is the seed of a drupe fruit

- Yeheb nut is the seed of a desert bush, Cordeauxia edulis

Nutrition

Constituents

Nuts are the source of energy and nutrients for the new plant. They contain a relatively large quantity of calories, essential unsaturated and monounsaturated fats including linoleic acid and linolenic acid, vitamins, and essential amino acids. Many nuts are good sources of vitamin E, vitamin B2, folate, fiber, and the essential minerals magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, copper, and selenium.[5] Nuts are most healthy in their raw unroasted form,[6]because roasting can significantly damage and destroy fats during the process.[7] Unroasted walnuts have twice as many antioxidants as other nuts or seeds.[6] It is controversial whether increasing dietary antioxidants confers benefit or harm.[8][9]

This table lists the percentage of various nutrients in four unroasted seeds.

| Name | Protein | Total Fat | Saturated Fat | Polyunsaturated Fat | Monounsaturated Fat | Carbohydrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almonds | 21.26 | 50.64 | 3.881 | 12.214 | 32.155 | 28.1 |

| Walnuts | 15.23 | 65.21 | 6.126 | 47.174 | 8.933 | 19.56 |

| Peanuts | 23.68 | 49.66 | 6.893 | 15.694 | 24.64 | 26.66 |

| Pistachio | 20.61 | 44.44 | 5.44 | 13.455 | 23.319 | 34.95 |

Health effects

People who eat nuts regularly have better health outcomes.[10] This includes less coronary heart disease (CHD), less cancer, and lower chances of death.[10][11]

Nuts were first linked to protection against CHD in 1993.[12] Eating various nuts such as almonds and walnuts can lower serum low density lipoprotein (LDL) concentrations. Although nuts contain various substances thought to possess cardioprotective effects, their omega 3 fatty acid profile is at least in part responsible for the hypolipidemic response.[13] Nuts have a very low glycemic index (GI)[14] due to their high unsaturated fat and protein content and relatively low carbohydrate content.[15] Consequently, dietitians frequently recommend that nuts be included in diets of people with insulin resistance such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus.[16] One study found that people who eat nuts live two to three years longer than those who do not.[17] However, this may be because people who eat nuts tend to eat less junk food.[18]

Other uses

The nut of the horse-chestnut tree (Aesculus species, especially Aesculus hippocastanum), is called a conker in the British Isles. Conkers are inedible because they contain toxic glucoside aesculin. They are used in a popular children's game, known as conkers, where the nuts are threaded onto a strong cord and then each contestant attempts to break their opponent's conker by hitting it with their own. Horse chestnuts are also popular slingshot ammunition.

Pre-historic consumption

Nuts, including acorns, pistachios, prickly water lillies, water chestnuts, and wild almonds, were a major part of the human diet 780,000 years ago. Prehistoric humans developed an assortment of tools to crack open nuts during the Pleistocene period.[19] The Aesculus californica (also known as the California buckeye or California horse-chestnut), was eaten by the Native Americans of California during famines, after the toxic constituents were leached out.

See also

References

- ↑ Alasalvar, Cesarettin; Shahidi, Fereidoon. Tree Nuts: Composition, Phytochemicals, and Health Effects (Nutraceutical Science and Technology). CRC. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8493-3735-2.

- ↑ Black, Michael H.; Halmer, Peter (2006). The encyclopedia of seeds: science, technology and uses. Wallingford, UK: CABI. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-85199-723-0.

- ↑ "Common Food Allergens". Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network. Archived from the original on 2007-06-13. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- ↑ Lina Sequeira. Certificate Biology 3. East African Publishers. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-9966-25-331-6. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ Kris-Etherton PM, Yu-Poth S, Sabaté J, Ratcliffe HE, Zhao G, Etherton TD (1999). "Nuts and their bioactive constituents: effects on serum lipids and other factors that affect disease risk". Am J Clin Nutr. 70 (3 Suppl): 504S–511S. PMID 10479223.

- 1 2 "Walnuts are the healthiest nut, say scientists". BBC News. March 27, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ "The Difference Between Raw, Pasteurized and Roasted Almonds". Legendary Foods.

- ↑ Baillie, J.K.; Thompson, A.A.R.; Irving, J.B.; Bates, M.G.D.; Sutherland, A.I.; MacNee, W.; Maxwell, S.R.J.; Webb, D.J. (2009). "Oral antioxidant supplementation does not prevent acute mountain sickness: double blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial". QJM. 102 (5): 341–8. PMID 19273551. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcp026.

- ↑ Bjelakovic G; Nikolova, D; Gluud, LL; Simonetti, RG; Gluud, C (2007). "Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 297 (8): 842–57. PMID 17327526. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842.

- 1 2 Aune, D; Keum, N; Giovannucci, E; Fadnes, LT; Boffetta, P; Greenwood, DC; Tonstad, S; Vatten, LJ; Riboli, E; Norat, T (5 December 2016). "Nut consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies.". BMC medicine. 14 (1): 207. PMID 27916000.

- ↑ Luo, C; Zhang, Y; Ding, Y; Shan, Z; Chen, S; Yu, M; Hu, FB; Liu, L (July 2014). "Nut consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". The American journal of clinical nutrition. 100 (1): 256–69. PMID 24847854. doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.076109.

- ↑ Sabaté J, Fraser GE, Burke K, Knutsen SF, Bennett H, Linsted KD (1993). "Effects of walnuts on serum lipid levels and blood pressure in normal men". Engl J Med. 328 (9): 603–607. doi:10.1056/NEJM199303043280902.

- ↑ Rajaram S, Hasso Haddad E, Mejia A, Sabaté J (2009) Walnuts and fatty fish influence different serum lipid fractions in normal to mildly hyperlipidemic individuals: a randomized controlled study. Am J Clin Nutr 2009, 89, 1657S-1663S.

- ↑ David Mendosa (2002). "Revised International Table of Glycemic Index (GI) and Glycemic Load (GL) Values". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ url=http://www.whfoods.com/genpage.php?tname=foodspice&dbid=20

- ↑ Josse AR, Kendall CW, Augustin LS, Ellis PR, Jenkins DJ (2007). "Almonds and postprandial glycemia — a dose response study". Metabolism. 56 (3): 400–404. PMID 17292730. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2006.10.024.

- ↑ Fraser GE, Shavlik DJ (2001). "Ten years of life: Is it a matter of choice?". Arch Intern Med. 161 (13): 1645–1652. PMID 11434797. doi:10.1001/archinte.161.13.1645.

- ↑ "ABC News: The Places Where People Live Longest". Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Remains of seven types of edible nuts and nutcrackers found at 780,000-year-old archaeological site". Scienceblog.com. February 2002. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

Further references

Albala, Ken 2014. Nuts A Global History. The Edible Series. ISBN 978-178023-282-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuts. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nut (fruit) |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- Linus Pauling Micronutrient Information Centre Nuts

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Nuts and their bioactive constituents: effects on serum lipids and other factors that affect disease risk

- Nut research

.jpg)