Nursultan Nazarbayev

| Nûrsûltan Nazarbayev | |

|---|---|

|

Нұрсұлтан Әбішұлы Назарбаев Nûrsûltan Äbişulı Nazarbayev | |

| |

| 1st President of Kazakhstan | |

|

Assumed office | |

| Prime Minister |

Sergey Tereshchenko Akezhan Kazhegeldin Nurlan Balgimbayev Kassym-Jomart Tokayev Imangali Tasmagambetov Daniyal Akhmetov Karim Massimov Serik Akhmetov Karim Massimov Bakhytzhan Sagintayev |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| 2nd Chairman of Nur Otan | |

|

Assumed office 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Bakhytzhan Zhumagulov |

| Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic | |

|

In office 22 February 1990 – 24 April 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Uzakbay Karamanov |

| Preceded by | Kilibay Medeubekov |

| Succeeded by | Yerik Asanbayev |

| First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakh SSR | |

|

In office 22 June 1989 – 14 December 1991 | |

| Preceded by | Gennady Kolbin |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Prime Minister of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic | |

|

In office 22 March 1984 – 27 July 1989 | |

| Chairman of the Supreme Soviet |

Bayken Ashimov Salamay Mukashev Zakash Kamaledinov Vera Sidorova Makhtay Sagdiyev |

| Preceded by | Bayken Ashimov |

| Succeeded by | Uzakbay Karamanov |

| Full member of the 28th Politburo | |

|

In office 14 July 1990 – 29 August 1991 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Nursultan Äbishuly Nazarbayev 6 July 1940 Chemolgan, Kazakh SSR, Soviet Union (now Ushkonyr, Kazakhstan) |

| Political party | Nur Otan (1999–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

Communist (1962–1991) Independent (1991–1999) |

| Spouse(s) | Sara Alpysqyzy Nazarbayeva (1962–present) |

| Children |

Dariga Dinara Aliya |

| Signature |

|

Nursultan Äbishulliy Nazarbayev[2] (Kazakh: Нұрсұлтан Әбішұлы Назарбаев, Nursultan Äbişulı Nazarbayev [nʊrsʊlˈtɑn æbəʃʊˈlə nɑzɑrˈbɑ.jɪf]; Russian: Нурсултан Абишевич Назарбаев, Nursultan Abishevich Nazarbayev [nʊrsʊlˈtan ɐˈbʲiʂɨvʲɪtɕ nəzɐrˈbajɪf]; born 6 July 1940) is the President of Kazakhstan. He has been the country's leader since 1989, when he was named First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR, and was elected the nation's first president following its independence from the Soviet Union in December 1991. He holds the title 'Leader of the Nation'.[3] In April 2015, Nazarbayev was re-elected with almost 98% of the vote.

Nazarbayev has suppressed dissent, been accused of human rights abuses by several human rights organizations, and presided over an authoritarian regime.[4] No election held in Kazakhstan since independence has met international standards.[5] In 2010, he announced reforms to encourage a multi-party system.[4]

In January 2017, President Nazarbayev proposed constitutional reforms that would delegate powers to the parliament.[6]

Early life

Nazarbayev was born in Chemolgan, a rural town near Almaty, when Kazakhstan was one of the republics of the Soviet Union.[7] His father was a poor labourer who worked for a wealthy local family until Soviet rule confiscated the family's farmland in the 1930s during Joseph Stalin's collectivization policy.[8] Following this, his father took the family to the mountains to live out a nomadic existence.[9]

His father avoided compulsory military service due to a withered arm he sustained when putting out a fire.[10] At the end of World War II the family returned to the village of Chemolgan, and Nazarbayev began to learn the Russian language.[11] He performed well at school, and was sent to a boarding school in Kaskelen.[12]

After leaving school he took up a one-year, government-funded scholarship at the Karaganda Steel Mill in Temirtau.[13] He also spent time training at a steel plant in Dniprodzerzhynsk, and therefore was away from Temirtau when riots broke out there over working conditions.[13] By 20, he was earning a relatively good wage doing "incredibly heavy and dangerous work" in the blast furnace.[14]

He joined the Communist Party in 1962, becoming a prominent member of the Young Communist League.[14] and full-time worker for the party, and attended the Karagandy Polytechnic Institute.[15] He was appointed secretary of the Communist Party Committee of the Karaganda Metallurgical Kombinat in 1972, and four years later became Second Secretary of the Karaganda Regional Party Committee.[15]

In his role as a bureaucrat, Nazarbayev dealt with legal papers, logistical problems and industrial disputes, as well as meeting workers to solve individual issues.[15] He later wrote that "the central allocation of capital investment and the distribution of funds" meant that infrastructure was poor, workers were demoralized and overworked, and centrally set targets were unrealistic; he saw the steel plant's problems as a microcosm for the problems for the Soviet Union as a whole.[16]

Rise to power

In 1984, Nazarbayev became the Prime Minister of Kazakhstan (chairman of the Council of Ministers), under Dinmukhamed Kunayev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan.[17] At the 16th session of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan in January 1986, Nazarbayev criticized Askar Kunayev, head of the Academy of Sciences, for not reforming his department. Dinmukhamed Kunayev, Nazarbayev's boss and Askar's brother, felt deeply angered and betrayed. Kunayev went to Moscow and demanded Nazarbayev's dismissal while Nazarbayev's supporters campaigned for Kunayev's dismissal and Nazarbayev's promotion.

Kunayev was ousted in 1986 and replaced by a Russian, Gennady Kolbin, who despite his office had little authority in Kazakhstan. Nazarbayev was named party leader on 22 June 1989--[17] only the second Kazakh (after Kunayev) to hold the post. He was Chairman of the Supreme Soviet (head of state) from 22 February to 24 April 1990.

On 24 April 1990, Nazarbayev was named the first President of Kazakhstan by the Supreme Soviet. He supported Russian President Boris Yeltsin against the attempted coup in August 1991 by Soviet hardliners.[18] Nazarbayev was close enough to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for Gorbachev to consider him for the post of Vice President of the Soviet Union; however, Nazarbayev turned the offer down.[19]

The Soviet Union disintegrated following the failed coup, though Nazarbayev was highly concerned with maintaining the close economic ties between Kazakhstan and Russia.[20] In the country's first presidential election, held on 1 December, he appeared alone on the ballot and won 91.5% of the vote.[21] On 21 December, he signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, taking Kazakhstan into the Commonwealth of Independent States.[22]

Presidency

Nazarbayev renamed the former State Defense Committees as the Ministry of Defense and appointed Sagadat Nurmagambetov as Defense Minister on 7 May 1992. The Supreme Council, under the leadership of Speaker Serikbolsyn Abdilin, began debating over a draft constitution in June 1992. The constitution created a strong executive branch with limited checks on executive power.[23]

Opposition political parties Azat, Zheltoqsan and the Republican Party, held demonstrations in Almaty from 10–17 June calling for the formation of a coalition government and the resignation of the government of Prime Minister Sergey Tereshchenko and the Supreme Council. The Parliament of Kazakhstan, composed of Communist Party legislators who had yet to stand in an election since the country gained its independence, adopted the constitution on 28 January 1993.[23]

An April 1995 referendum extended his term until 2000. He was re-elected in January 1999 and again in December 2005. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe criticized the last presidential election as falling short of international democratic standards.[24] On 18 May 2007, the Parliament of Kazakhstan approved a constitutional amendment which allowed the incumbent president—himself—to run for an unlimited number of five-year terms. This amendment applied specifically and only to Nazarbayev: the original constitution's prescribed maximum of two five-year terms will still apply to all future presidents of Kazakhstan.[25]

Nazarbayev appointed Altynbek Sarsenbayev, who at the time served as the Minister of Culture, Information and Concord, the Secretary of the Kazakh Security Council, replacing Marat Tazhin, on 4 May 2001. Tazhin became the Chairman of the National Security Council, replacing Alnur Musayev. Musayev became the head of the Guards' Service of the President.[26]

Notwithstanding Kazakhstan's membership in the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation), under Nazarbayev the country has had good relations with Israel. Diplomatic relations were established in 1992 and President Nazarbayev paid official visits to Israel in 1995 and 2000.[27] Bilateral trade between the two countries amounted to $724 million in 2005.

In 1994, Nazarbayev suggested the move of the capital from Almaty to Astana, and the official shift of the capital happened on 10 December 1997.[28]

On 4 December 2005, new Presidential elections were held and President Nazarbayev won by an overwhelming majority of 91.15% (from a total of 6,871,571 eligible participating voters). Nazarbayev was sworn in for another seven-year term on 11 January 2006.

.jpg)

In 2009, former UK cabinet minister Jonathan Aitken released a biography of the Kazakhstani leader entitled Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan. The book takes a generally pro-Nazarbayev stance, asserting in the introduction that he is mostly responsible for the success of modern Kazakhstan.[29]

December 2011 saw the 2011 Mangystau riots, described by the BBC as the biggest opposition movement of his time in power.[30] On 16 December 2011, demonstrations in the oil town of Zhanaozen clashed with police on the country's Independence Day. Fifteen people were shot dead by security forces and almost 100 were injured. Protests quickly spread to other cities but then died away. The subsequent trial of demonstrators uncovered mass abuse and torture of detainees.[30]

Nazarbayev suggested in 2014 that Kazakhstan should change its name to "Kazakh Yeli" ("Country of the Kazakhs"), for the country to attract better and more foreign investment, since "Kazakhstan" by its name is associated with other "-stan" countries. Nazarbayev noted Mongolia receives more investment than Kazakhstan because it is not a "-stan" country, even though it is in the same neighborhood, and not as stable as Kazakhstan. However, he is letting the people decide on whether the country should change its name.[31][32]

The role of Nazarbayev and his political reforms was acknowledged by Daniel Witt, Vice Chairman of the Eurasia Foundation. He noted: "[President] Nazarbayev has led Kazakhstan through difficult times and into an era of prosperity and growth. He has demonstrated that he values his U.S. and Western alliances and is committed to achieving democratic governance."[33]

In December 2012, Nazarbayev outlined a forward-looking national strategy called the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy.

Nazarbayev always emphasized the role of education in the nation's social development. In order to make education affordable, he introduced educational grant "Orken" for the talented youth of Kazakhstan.[34]

Allegations of corruption

.jpg)

Over the course of Nazarbayev's presidency, there have been an increasing number of accusations of corruption and favoritism directed against Nazarbayev and his circle. Critics say that the country's government has come to resemble a clan system.[35]

According to The New Yorker, in 1999 Swiss banking officials discovered $8.5 billion in an account apparently belonging to Nazarbayev; the money, intended for the Kazakh treasury, had in part been transferred through accounts linked to James Giffen.[36] Subsequently, Nazarbayev successfully pushed for a parliamentary bill granting him legal immunity, as well as another designed to legalize money laundering, angering critics further.[36] When Kazakh opposition newspaper Respublika reported in 2002 that Nazarbayev had in the mid-1990s secretly stashed away $1 billion of state oil revenue in Swiss bank accounts, the decapitated carcass of a dog was left outside the newspaper's offices, with a warning reading "There won't be a next time"; the dog's head later turned up outside editor Irina Petrushova's apartment, with a warning reading "There will be no last time."[37][38][39] The newspaper was firebombed as well.[39]

In May 2007, the Parliament of Kazakhstan approved a constitutional amendment which would allow Nazarbayev to seek re-election as many times as he wishes. This amendment applies specifically and only to Nazarbayev, since it states that the first president will have no limits on how many times he can run for office, but subsequent presidents will be held to a five-year term.[40]

As of 2015, Kazakhstan has never held an election meeting international standards.[4][5]

Eurasian Economic Union

In 1994, Nazarbayev suggested the idea of creating a "Eurasian Union" during a speech at Moscow State University.[41][42][43] On 29 May 2014, Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan signed a treaty to create a Eurasian Economic Union which created a single economic space of 170 million people and came into effect in January 2015.[44] Nazarbayev said shortly after the treaty was signed, "We see this as an open space and a new bridge between the growing economies of Europe and Asia."[44]

Environmental issues

In his 1998 autobiography, Nazarbayev wrote that "The shrinking of the Aral Sea, because of its scope, is one of the most serious ecological disasters being faced by our planet today. It is not an exaggeration to put it on the same level as the destruction of the Amazon rainforest."[45] He called on Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the wider world to do more to reverse the environmental damage done during the Soviet era.[46]

Nuclear issues

Kazakhstan inherited from the Soviet Union the world's fourth largest stockpile of nuclear weapons. Within four years of independence, Kazakhstan possessed zero nuclear weapons.[47] In one of the new government’s first major decisions, Nazarbayev closed the Soviet nuclear test site at Semipalatinsk (Semei), where 456 nuclear tests had been conducted by the Soviet military.[48]

During the Soviet era, over 500 military experiments with nuclear weapons were conducted by scientists in the Kazakhstan region, mostly at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, causing radiation sickness and birth defects.[49] As the influence of the Soviet Union waned, Nazarbayev closed the site.[50] He later claimed that he had encouraged Olzhas Suleimenov's anti-nuclear movement in Kazakhstan, and was always fully committed to the group's goals.[51] In what was dubbed 'Project Sapphire', the Kazakhstan and United States government worked closely to dismantle former Soviet weapons stored in the country, with the Americans agreeing to fund over $800 million in transportation and 'compensation' costs.[52]

Nazarbayev encouraged the United Nations General Assembly to establish 29 August as the International Day Against Nuclear Tests. In his article he has proposed a new Non-Proliferation Treaty "that would guarantee clear obligations on the part of signatory governments and define real sanctions for those who fail to observe the terms of the agreement."[53] He signed a treaty authorizing the Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone on 8 September 2006.

In an oped in The Washington Times, Nazarbayev called for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty to be modernized and better balanced.[54]

In March 2016, Nazarbayev released his "Manifesto: The World. The 21st century."[55] In this manifest the Kazakhstan President called for expanding and replicating existing nuclear-weapon-free zones and stressed the need to modernise existing international disarmament treaties.[56]

Iran

In a speech given on 15 December 2006 marking the 15th anniversary of Kazakhstan's independence, Nazarbayev stated he wished to join with Iran in support of a single currency for all Central Asian states and intended to push the idea forward with Iran's then President Ahmadinejad on an upcoming visit. The Kazakh president also reportedly criticized Iran as a terrorism-supporting state. The Kazakh Foreign Ministry released a statement on 19 December, saying the reports were mistaken and contradictory to what the president actually meant.[57]

Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy

Nazarbayev unveiled in his 2012 State of the Nation the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy, a long-term strategy to ensure future growth prospects of Kazakhstan, and position Kazakhstan as one of the 30 most developed nations in the world.[58]

Religion

Nazarbayev has put forward the initiative of holding a forum of world and traditional religions in the capital of Kazakhstan, Astana. Earlier the organizers of similar events were only representatives of leading religions and denominations. Among other similar events aimed at establishing interdenominational dialogue were the meetings of representatives of world religions and denominations held in Assisi, Italy in October 1986 and January 2002.[59] The first Congress of World and Traditional Religions which gathered in 2003 allowed the leaders of all major religions to develop prospects for mutual cooperation.

Nazarbayev espoused anti-religious views during the Soviet era;[60] he has now made an effort to highlight his Muslim heritage by performing the Hajj pilgrimage,[60] and supporting mosque renovations.[61]

Under the leadership of Nazarbayev, the Republic of Kazakhstan has enacted some degrees of multiculturalism in order to retain and attract talents from diverse ethnic groups among its citizenry, and even from nations that are developing ties of cooperation with the country, in order to coordinate human resources onto the state-guided path of global market economic participation. This principle of the Kazakh leadership has earned it the name "Singapore of the Steppes".[62]

However, in 2012 Nazarbayev proposed reforms, which were later enacted by the parliament, imposing stringent restrictions on religious practices.[63] Religious groups were required to re-register, or face closure.[64] The initiative was explained as an attempt to combat extremism. However, under the new law many minority religious groups are deemed illegal. In order to exist on a local level, a group must have more than 50 members; on a regional level – more than 500; on the national level – more than 5000.[63]

Nazarbayev made remarks on the veil, highlighting the country's culture with words "We are Turks, not Arabs" in an open reference to the Turkic heritage.[65]

Nationalism

Putin's remarks on the historicity of Kazakhstan[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] led to a severe response from Nazarbayev.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82]

Human rights record

Kazakhstan's human rights situation under Nazarbayev is uniformly described as poor by independent observers. Human Rights Watch says that "Kazakhstan heavily restricts freedom of assembly, speech, and religion. In 2014, authorities closed newspapers, jailed or fined dozens of people after peaceful but unsanctioned protests, and fined or detained worshippers for practicing religion outside state controls. Government critics, including opposition leader Vladimir Kozlov, remained in detention after unfair trials. In mid-2014, Kazakhstan adopted new criminal, criminal executive, criminal procedural, and administrative codes, and a new law on trade unions, which contain articles restricting fundamental freedoms and are incompatible with international standards. Torture remains common in places of detention."[83]

Kazakhstan is ranked 161 out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders.[84]

Rule of law

According to a US government report released in 2014, in Kazakhstan:

The law does not require police to inform detainees that they have the right to an attorney, and police did not do so. Human rights observers alleged that law enforcement officials dissuaded detainees from seeing an attorney, gathered evidence through preliminary questioning before a detainee’s attorney arrived, and in some cases used corrupt defense attorneys to gather evidence. [...]The law does not adequately provide for an independent judiciary. The executive branch sharply limited judicial independence. Prosecutors enjoyed a quasi-judicial role and had the authority to suspend court decisions. Corruption was evident at every stage of the judicial process. Although judges were among the most highly paid government employees, lawyers and human rights monitors alleged that judges, prosecutors, and other officials solicited bribes in exchange for favorable rulings in the majority of criminal cases.[85]

Kazakhstan's global rank in the World Justice Project's 2015 Rule of Law Index was 65 out of 102; the country scored well on "Order and Security" (global rank 32/102), and poorly on "Constraints on Government Powers" (global rank 93/102), "Open Government" (85/102) and "Fundamental Rights" (84/102, with a downward trend marking a deterioration in conditions).[86]

The National plan "100 concrete steps" introduced by President Nazarbayev included measures to reform the court system of Kazakhstan. The implementation of the national plan resulted in Kazakhstan's transition from a five-tier judicial system to a three-tier one in early 2016.[87]

Foreign policy

During Nazarbayev's presidency the main principle of Kazakhstan's international relations was multi-vector foreign policy, which was based on initiatives to establish friendly relations with foreign partners.[88] U.S. President-elect Donald Trump lauded Nazabayev's leadership and called Kazakhstan's achievements under his presidency a "miracle" during their phone call on November 30, 2016.[89]

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu conducted his first ever visit to Kazakhstan in mid-December, 2016, when he met with Nazarbayev. The two countries signed agreements on research and development, aviation, civil service commissions and agricultural cooperation, as well as a declaration on establishing an agricultural consortium.[90]

Personal life

Nazarbayev is married to Sara Alpysqyzy Nazarbayeva, and they have three daughters – Dariga, Dinara and Aliya.

Nurali Aliyev, the grandson of Nazarbayev, was named in the Panama Papers.[91]

Honours

Kazakhstan

- Order of the Golden Eagle

- Medal "Astana"

- Medal "10 Years of the Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

- Medal "10th Anniversary of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

- Medal "10th Anniversary of the Constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Railway of Kazakhstan"

- Medal "10 Years of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

- Medal "50 Years of the Virgin Lands"

- Jubilee Medal "60 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945"

- Medal "10 Years of the City of Astana"

- Medal "20 Years of the Independence of the Republic of Kazakhstan"

Soviet Union

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour

- Order of the Badge of Honour

- Medal "For the Development of Virgin Lands"

- Jubilee Medal "70 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR"

Russian Federation

- Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-Called

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 1000th Anniversary of Kazan"

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of Saint Petersburg"

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 850th Anniversary of Moscow"

- The Order of Alexander Nevsky

- The Order of Akhmad Kadyrov (Chechnya)

Foreign awards

- Austria: Grand Star of the Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria

- Azerbaijan: Heydar Aliyev Order

- Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

- Croatia: Grand Order of King Tomislav

- Egypt: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Nile

- Estonia: Collar of the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana

- Finland: Commander Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of the White Rose of Finland

- Finland: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Lion of Finland

- France: Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur

- Greece: Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer

- Hungary: Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary

- Italy: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- Japan: Order of the Chrysanthemum

- Latvia: 1st Class with Chain of the Order of the Three Stars

- Lithuania: Grand Cross of the Order of Vytautas the Great (5 May 2000)[92]

- Luxembourg: Grand Cross of the Order of the Oak Crown

- Monaco: Grand Cross of the Order of Saint-Charles

- Poland: Order of the White Eagle

- Qatar: Order of Independence

- Romania: Sash of the Order of the Star of Romania

- Serbia: Order of the Republic of Serbia

- Slovakia: Grand Cross (or 1st Class) of the Order of the White Double Cross (2007)[93]

- Spain: Knight Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (2017)[94]

- Tajikistan: Order of Ismoili Somoni

- Turkey: First Class of the Order of the State of Republic of Turkey (22 October 2009)[95]

- United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Ukraine: Order of Liberty (Ukraine)

- Ukraine: Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 1st Class

- United Arab Emirates: Order of Zayed

Other

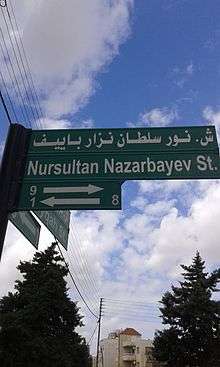

- Jordan: A street in Amman is named after him.

- World Turks Qurultai: Turk El Ata (Spiritual Leader of the Turkic People).[96]

See also

- Counter-terrorism in Kazakhstan

- Government of Kazakhstan

- List of national leaders

- Politics of Kazakhstan

References

- Specific

- ↑ "President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev is the head of the Nur Otan party". Enews.ferghana.ru. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Principles of International Politics – Bruce Bueno de Mesquita – Google Books. Books.google.com. 14 January 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Walker, Shaun (2015-04-24). "Kazakhstan election avoids question of Nazarbayev successor". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-09-08.

- 1 2 3 Pannier, Bruce (11 March 2015). "Kazakhstan's long term president to run in show election – again". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

Nazarbaev has clamped down on dissent in Kazakhstan, and the country has never held an election judged to be free or fair by the West.

- 1 2 Chivers, C.J. (6 December 2005). "Kazakh President Re-elected; voting Flawed, Observers Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Kazakhstan has never held an election that was not rigged.

- ↑ "Kazakh Leader Ready to Devolve Some Powers to Parliament, Cabinet". Voice of America.

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 11

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 16

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 20

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 21

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 22

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 23

- 1 2 Nazarbayev 1998, p. 24

- 1 2 Nazarbayev 1998, p. 26

- 1 2 3 Nazarbayev 1998, p. 27

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 28

- 1 2 Sally N. Cummings (2002). Power and change in Central Asia. Psychology Press. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-415-25585-1. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 73

- ↑ "Union of Soviet Socialist Republics - historical state, Eurasia".

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 81

- ↑ James Minahan (1998). Miniature empires: a historical dictionary of the newly independent states. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-313-30610-5. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 82

- 1 2 Karen Dawisha; Bruce Parrott (1994). Russia and the new states of Eurasia: the politics of upheaval. Cambridge University Press. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-521-45895-5. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights – Elections. Archived 9 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan lifts term limits on long-ruling leader", Los Angeles Times. Latimes.com (19 May 2007). Retrieved on 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Robert D'A. Henderson (21 July 2003). Brassey's International Intelligence Yearbook: 2003 Edition. Brassey's. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-57488-550-7. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Content at the Wayback Machine (archived 6 October 2006). Retrieved on 3 February 2011.

- ↑ "Official site of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan – Astana". Akorda.kz. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Aitken, Jonathan (2009). Nazarbayev and the Making of Kazakhstan. London: Continuum. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-1-4411-5381-4.

- 1 2 "Abuse claims swamp Kazakh oil riot trial". BBC. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ "WorldViews". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "BBC News – Kazakhstan: President suggests renaming the country". British Broadcasting Corporation. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan's Presidential Election Shows Progress". Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Kazakh President amends decree on educational grant for talented youngsters". Kazinform.

- ↑ Martha Brill Olcott (1 September 2010). Kazakhstan: Unfulfilled Promise. Carnegie Endowment. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-87003-299-8.

- 1 2 Seymour M. Hersh (9 July 2001). "The Price of oil". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Peter Baker (11 June 2002). "As Kazakh scandal unfolds, Soviet-style reprisals begin". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Casey Michel (7 August 2015). "Kazakhstan Goes After Opposition Media in New York Federal Court". The Diplomat.

- 1 2 Danny O'Brien (4 August 2015). "How Kazakhstan is Trying to Use the US Courts to Censor the Net". Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- ↑ Holley, David (19 May 2007). "Kazakhstan lifts term limits on long-ruling leader". LA Times. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Holding-Together Regionalism: Twenty Years of Post-Soviet Integration. Libman A. and Vinokurov E. (Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2012, p. 220.)

- ↑ "Президент Республики Казахстан Н. А. Назарбаев о евразийской интеграции. Из выступления в Московском государственном университете им. М. В. Ломоносова 29 марта 1994 г.".

- ↑ Alexandrov, Mikhail. Uneasy Alliance: Relations Between Russia and Kazakhstan in the Post-Soviet Era, 1992-1997. Greenwood Press, 1999, p. 229. ISBN 978-0-313-30965-6

- 1 2 "Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan sign 'epoch' Eurasian Economic Union". RT.

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 42

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 41

- ↑ "NTI Kazakhstan Profile". Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI).

- ↑ "Kazakhstan and US Renew Nonproliferation Partnership". thediplomat.com.

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 141

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 143

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 142

- ↑ Nazarbayev 1998, p. 150

- ↑ Right time for building global nuclear security. Chicago Tribune (11 April 2010). Retrieved 3 February 2011. Archived 10 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ oped, The Washington Times

- ↑ "Manifesto: The World. The 21st century". www.akorda.kz.

- ↑ "Manifest by Kazakh President Calls for Global Nuclear Disarmament, Steps to End Global Conflicts". astanatimes.com.

- ↑ Kazakhstan dismisses alleged anti-Iran comments from president at the Wayback Machine (archived 8 March 2008). Retrieved on 3 February 2011.

- ↑ "Strategy 2050: Kazakhstan's Road Map to Global Success". EdgeKZ.

- ↑ Congress of World Religions – About Congress of leaders of world and traditional religions. Religions-congress.org (15 October 2007). Retrieved on 3 February 2011.

- 1 2 Ideology and National Identity in Post-Communist Foreign Policies By Rick Fawn, p. 147

- ↑ Moscow's Largest Mosque to Undergo Extension Archived 4 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Preston, Peter (19 July 2009). "How Nursultan became the most loved man on Earth". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Leonard, Peter (29 September 2011). "Kazakhstan: Restrictive Religion Law Blow To Minority Groups". Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan: Religion Law Restricting Faith in the Name of Tackling Extremism?". EurasiaNet.org. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "LiveLeak.com - We Are Turks, Not Arabs".

- ↑ Diplomat, Casey Michel, The. "Putin’s Chilling Kazakhstan Comments".

- ↑ Traynor, Ian (1 September 2014). "Kazakhstan is latest Russian neighbour to feel Putin's chilly nationalist rhetoric".

- ↑ "Kazakhs Worried After Putin Questions History of Country's Independence".

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin Continues Soviet Rhetoric by Questioning Kazakhstan's 'Created' Independence". 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "LiveLeak.com - Putin: 'Kazakhstan Was Never a State'".

- ↑ Trilling, David (30 August 2014). "As Kazakhstan’s Leader Asserts Independence, Did Putin Just Say, ‘Not So Fast’?" – via EurasiaNet.

- ↑ Brletich, Samantha. "The Crimea Model: Will Russia Annex the Northern Region of Kazakhstan?".

- ↑ "Russian and Kazakh Leaders Exchange Worrying Statements".

- ↑ "Nazarbayev's Severe Response to Putin".

- ↑ Homepage TR (22 September 2015). "Nazarbayev vs Putin" – via YouTube.

- ↑ "LiveLeak.com - Nazarbayev Gives Putin a History Lesson".

- ↑ Lillis, Joanna (27 January 2016). "Kazakhstan creates its own Game of Thrones to defy Putin and Borat".

- ↑ "New Kazakh TV series a riposte to Putin and Borat".

- ↑ Lillis, Joanna (6 January 2015). "Kazakhstan Celebrates Statehood in Riposte to Russia" – via EurasiaNet.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan MP responds to Vladimir Putin's statement on lack of statehood in Kazakhstan - Politics - Tengrinews".

- ↑ Najibullah, Farangis (3 September 2014). "Putin Downplays Kazakh Independence, Sparks Angry Reaction" – via Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

- ↑ Michel, Casey (19 January 2015). "Even Vladimir Putin's Authoritarian Allies Are Fed Up With Russia's Crumbling Economy".

- ↑ Human Rights Watch, World Report 2015: Kazakhstan, accessed October 2015.

- ↑ "World Press Freedom Index 2014". Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2013: Kazakhstan", released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. Retrieved on November 1, 2015

- ↑ "Rule of Law Index 2015". World Justice Project.

- ↑ "Kazakh President instructs to improve court system". kazinform.

- ↑ "Nazarbayev's trust-based relations with foreign partners help promote Kazakhstan's interests". www.inform.kz.

- ↑ "Kazakhstan: Trump talked up leader's ‘miracle’ in call". thehill.com.

- ↑ "PM Netanyahu meets with Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev". mfa.gov.il.

- ↑ Lavrov, Vlad; Velska, Irene (4 April 2016). "Kazakhstan: President’s Grandson Hid Assets Offshore - The Panama Papers". OCCRP.

- ↑ Lithuanian Presidency, Lithuanian Orders searching form

- ↑ Slovak republic website, State honours: 1st Class in 2007 (click on "Holders of the Order of the 1st Class White Double Cross" to see the holders' table)

- ↑ "Spanish Official Journal. Royal Decree 677/2017, 23 june". Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ↑ "Presidency of the Republic of Turkey (Photo)". Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Declaration". qurultai.org (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- General

- Nazarbayev, Nursultan (1998), Nursultan Nazarbayev: My Life, My Times and My Future..., Pilkington Press, ISBN 1899044191

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nursultan Nazarbayev. |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Bayken Ashimov |

Prime Minister of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic 1984–1989 |

Succeeded by Uzaqbay Qaramanov |

| Preceded by Kilibay Medeubekov |

Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic 1990 |

Succeeded by Erik Asanbayev |

| New office | President of Kazakhstan 1991–present |

Incumbent |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Gennady Kolbin |

First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakh SSR 1989–1991 |

party dissolved |