Notiomastodon

| Notiomastodon Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene-Early Holocene (possible Early Pleistocene record) ~1.2–0.006 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | †Gomphotheriidae |

| Genus: | †Notiomastodon Cabrera, 1929 |

| Species: | N. platensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Notiomastodon platensis (Ameghino, 1888 [originally Mastodon]) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Notiomastodon is an extinct proboscidean genus of gomphothere (a distant relative to modern Elephants) endemic to South America from the Pleistocene to the Holocene[1] living for approximately 1.794 million years.

Taxonomy

Proboscideans in South America were first described by Georges Cuvier in 1806[2] but failed to given them specific names beyond "Mastodon". It was Fischer in 1814 who gave the “mastodonte des cordillères” specimen the first specific name "Mastotherium hyodon".[3]:340In 1824, Cuvier gave the specific names of "Mastodon andium" to the “mastodonte des cordillères” specimen, and "Mastodon humboldtii" to the “mastodonte humboldien”.[4] Due to the Principle of Priority, this means that "Mastodon andium" was invalid, as "Mastotherium hyodon" was named first from the same specimen. Today, neither tooth is considered diagnostic to any specific taxon.[5] Notiomastodon,[nb 1] "southern mastodon" was named by Cabrera (1929). It was assigned to Gomphotheriidae by Carroll (1988).

For centuries, the taxonomy of gompotheres, including Notiomastodon had been subject to debate, with many genus and species names for similar South American Gompotheres. The species genus is currently under dispute, whether it should belong to Notiomasodon or Stegomastodon[5][7][8] as regardless of genus, the species is considered synonymous with Haplomastodon by most authors, as the specimens were not considered morphologically distinct from this species.[9][10][11] This article treats Notiomastodon separately because in phylogenetic analyses, Notiomastodon/Stegomastodon platensis specimens are not sister taxa, which would make the genus Polyphyletic.[5][12][13] However some authors think that this is inconclusive, as they think the North American Stegomastodon material is too scarce and fragmentary to make a definitive statement [7]

Evolution

Notiomastodon belongs to the family Gomphotheriidae, a group of animals distantly related to modern elephants and mammoths. Notiomastodon seems to have had a 4 million year long ghost lineage, diverging from the clade that contains Rhynchotherium and Cuvieronius around the Late Miocene. This would imply that Notiomastodon had been evolving in southern Central America where the fossils are poorly sampled, prior to its migration into South America during the Pliocene or Pleistocene.[5]

Phylogenetic position among trilophodont Gomphotheres according to Mothé et al., 2016:[12]

| †Gomphotheriidae (Gomphotheres) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

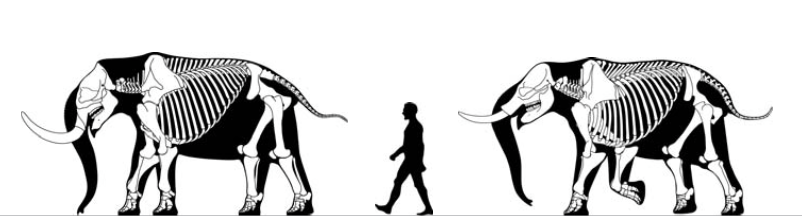

Notiomastodon platensis is known from MECN 82, a 35-year-old male that would be approximately 2.52 metres (8.3 ft) tall, with an estimated weight of 4.4 tonnes (4.3 long tons; 4.9 short tons).[14] It had two tusks on either side of its trunk, like other members of Gomphotheriidae. Unlike close relative Cuvieronius its tusks were not twisted, however their length and shape are observed as greatly variable depending on the individual.[5]

Paleobiogeography

Notiomastodon has been described as the 'lowland gomphothere'.[9] The genus tended to inhabit seasonally dry, open forests, with a range lining most of the South American coastline and lowland interior, bar the Guiana Shield, with particularly large concentrations along the coast of Peru and in northeastern Brazil.[15]

Whereas the other representative of South American gomphotheres, Cuvieronius, inhabited the mountainous Andes region from Ecuador to southern Peru and Bolivia, as well as lowland areas in north-east Peru [5]

The diet composition of Notiomastodon varied widely depending on location, but probably primarily consisted of a mix of C3 shrubs and C4 grasses, whilst also serving as a primary disperser of the seeds for a variety of different plant species.[16]

Behaviour

Notiomastodon probably had a similar population structure and behaviour to extant elephants.[17]

Notes

- ↑ From the Ancient Greek: νότιος (nótios, "southern")[6]

References

- ↑ Shoshani, Jeheskel; Tassy, Pascal (2005). "Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior". Quaternary International. 126-128: 5–20. ISSN 1040-6182. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011.

- ↑ Cuvier, Georges (1806). "Sur différentes dents du genre des mastodontes, mais d'espèces moindres que celle de l'Ohio, trouvées en plusieurs lieux des deux continents". Annales du Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle. 7: 401–420.

- ↑ Fischer, Gotthelf (1813). Zoognosia tabulis synopticis illustrata in Usum Praelectionem Academiae Imperialis Medico-Chirurgicae Mosquensis Edita: Vol 3. Classium, ordinum, generum illustratione perpetua aucta [Illustrated Zoognosia in Synoptic Tables, Produced from Lectures in the Imperial Medico-Surgical Academy of Moscow by the Author, Gotthelf Fischer: Vol. 3, Classes, Orders, Genera, Enlarged Throughout with Illustration] (in Latin). 3 (1 ed.). Moscow: Nikolai Sergeyevich Vsevolozhsky.

- ↑ Cuvier, Georges (1824). "Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles, ou l'on rétablit les caractères de plusieurs animaux dont les révolutions du globe ont détruit les espèces".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mothé, Dimila; dos Santos Avilla, Leonardo; Asevedo, Lidiane; Borges-Silva, Leon; Rosas, Mariane; Labarca-Encina, Rafael; Souberlich, Ricardo; Soibelzon, Esteban; Roman-Carrion, José Luis; Ríos, Sergio D.; Rincon, Ascanio D.; Cardoso de Oliveira, Gina; Pereira Lopes, Renato (30 September 2016). "Sixty years after ‘The mastodonts of Brazil’: The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae)". Quaternary International. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ↑ νότιος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- 1 2 Labarca, R.; Alberdi, M.T.; Prado, J.L.; Mansilla, P.; Mourgues, F.A. (18 April 2016). "Nuevas evidencias acerca de la presencia de Stegomastodon platensis Ameghino, 1888, Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae, en el Pleistoceno tardío de Chile central/New evidences on the presence of Stegomastodon platensis Ameghino, 1888, Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae, in the Late Pleistocene of Central Chile". Estudios Geológicos. 72.

- ↑ Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo (15 February 2015). "Mythbusting evolutionary issues on South American Gomphotheriidae (Mammalia: Proboscidea)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 110: 23–25. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- 1 2 Lucas, Spencer G.; Yuan, Wang; Min, Liu (2013-01-01). "The palaeobiogeography of South American gomphotheres". Journal of Palaeogeography. 2 (1): 19–40. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1261.2013.00015.

- ↑ Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S.; Cozzuol, Mario A. (2012). "The South American Gomphotheres (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae): Taxonomy, Phylogeny, and Biogeography". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. ISSN 1064-7554. doi:10.1007/s10914-012-9192-3.

- ↑ Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S.; Cozzuol, Mário; Winck, Gisele R. (25 October 2012). "Taxonomic revision of the Quaternary gomphotheres (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the South American lowlands". Quaternary International. 276-277: 2–7. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- 1 2 Mothé, Dimila; Ferretti, Marco P.; Avilla, Leonardo S. (12 January 2016). "The Dance of Tusks: Rediscovery of Lower Incisors in the Pan-American Proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon Revises Incisor Evolution in Elephantimorpha". PLOS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147009.

- ↑ Ferretti, Marco P. (2010). "Anatomy of Haplomastodon chimborazi (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the late Pleistocene of Ecuador and its bearing on the phylogeny and systematics of south American gomphotheres". Geodiversitas. 32 (4): 663–721.

- ↑ Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- ↑ Dantas, Mário André Trindade; Xavier, Márcia Cristina Teles; França, Lucas de Melo; Cozzuol, Mario Alberto; Ribeiro, Adauto de Souza; Figueiredo, Ana Maria Graciano; Kinoshita, Angela; Baffa, Oswaldo (2013-12-13). "A review of the time scale and potential geographic distribution of Notiomastodon platensis (Ameghino, 1888) in the late Pleistocene of South America" (PDF). Quaternary International. Quaternary in South America: recent research initiatives. 317: 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.06.031.

- ↑ Asevedo, Lidiane; Winck, Gisele R.; Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S. (2012). "Ancient diet of the Pleistocene gomphothere Notiomastodon platensis (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) from lowland mid-latitudes of South America: Stereomicrowear and tooth calculus analyses combined". Quaternary International. 255: 42–52. ISSN 1040-6182. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.08.037.

- ↑ Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S.; Winck, Gisele R. (26 November 2010). "Population structure of the gomphothere Stegomastodon waringi (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the Pleistocene of Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 82. ISSN 0001-3765. Retrieved 4 May 2017.