Nosferatu

| Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | F. W. Murnau |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Henrik Galeen |

| Based on |

Dracula by Bram Stoker |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Hans Erdmann |

| Cinematography | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Film Arts Guild |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | Germany |

| Language |

|

Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (translated as Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror; or simply Nosferatu) is a 1922 German Expressionist horror film, directed by F. W. Murnau, starring Max Schreck as the vampire Count Orlok. The film, shot in 1921 and released in 1922, was an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897). Various names and other details were changed from the novel: for instance, "vampire" became "Nosferatu" and "Count Dracula" became "Count Orlok".

Stoker's heirs sued over the adaptation, and a court ruling ordered that all copies of the film be destroyed. However, a few prints of Nosferatu survived, and the film came to be regarded as an influential masterpiece of cinema.[1][2]

The film was released in the United States on 3 June 1929, seven years after its original premiere in Germany.

Plot

In 1838, Thomas Hutter lives in the German city of Wisborg (the actual city of Wismar where part of the film was shot, but using the name the city took while under Swedish rule after the Thirty Years' War). His employer, Knock, sends Hutter to Transylvania to visit a new client named Count Orlok. Hutter entrusts his loving wife Ellen to his good friend Harding and Harding's sister Annie, before embarking on his long journey. Nearing his destination in the Carpathian Mountains, Hutter stops at an inn for dinner. The locals become frightened by the mere mention of Orlok's name and discourage him from traveling to his castle at night, warning of a werewolf on the prowl. The next morning, Hutter takes a coach to a high mountain pass, but the coachmen declines to take him any further than the bridge as nightfall is approaching. A black-swathed coach appears after Hutter crosses the bridge and the coachman gestures for him to climb aboard. Hutter is welcomed at a castle by Count Orlok. When Hutter is eating dinner and accidentally cuts his thumb, Orlok tries to suck the blood out, but his repulsed guest pulls his hand away.

Hutter wakes up to a deserted castle the morning after and notices fresh punctures on his neck which, in a letter he sends by courier on horseback to be delivered to his devoted wife, he attributes to mosquitoes. That night, Orlok signs the documents to purchase the house across from Hutter's own home in Wisborg and notices a photo of Hutter's wife remarking that she has a lovely neck. Reading a book about vampires that he took from the local inn, Hutter starts to suspect that Orlok is Nosferatu, the "Bird of Death." He cowers in his room as midnight approaches, but there is no way to bar the door. The door opens by itself and Orlok enters, his true nature finally revealed, and Hutter hides under the bedcovers and falls unconscious. At the same time this is happening, his wife awakens from her sleep and in a trance walks towards the balcony and onto the railing. Alarmed, Harding shouts Ellen's name and she faints while he asks for a doctor. After the doctor arrives, she shouts Hutter's name remaining in the trance and apparently able to see Orlok in his castle threatening her unconscious husband. The doctor believes this trance-like state is due to "blood congestion". The next day, Hutter explores the castle. In its crypt, he finds the coffin in which Orlok is resting dormant. Hutter becomes horrified and dashes back to his room. Hours later from the window, he sees Orlok piling up coffins on a coach and climbing into the last one before the coach departs. Hutter escapes the castle through the window, but is knocked unconscious by the fall and awakens in a hospital.

When he is sufficiently recovered, he hurries home. Meanwhile, the coffins are shipped down river on a raft. They are transferred to a schooner, but not before one is opened by the crew, revealing a multitude of rats. The sailors on the ship get sick one by one; soon all but the captain and first mate are dead. Suspecting the truth, the first mate goes below to destroy the coffins. However, Orlok awakens and the horrified sailor jumps into the sea. Unaware of his danger, the captain becomes Orlok's latest victim when he ties himself to the wheel. When the ship arrives in Wisborg, Orlok leaves unobserved, carrying one of his coffins, and moves into the house he purchased. The next morning, when the ship is inspected, the captain is found dead. After examining the logbook, the doctors assume they are dealing with the plague. The town is stricken with panic, and people are warned to stay inside.

There are many deaths in the town, which are blamed on the plague. Knock, who had been committed to a psychiatric ward, escapes after murdering the warden. The townspeople give chase, but he eludes them by climbing a roof, then using a scarecrow. Meanwhile, Orlok stares from his window at the sleeping Ellen. Against her husband's wishes, Ellen had read the book he found. The book claims that the way to defeat a vampire is for a woman who is pure in heart to distract the vampire with her beauty all through the night. She opens her window to invite him in, but faints. (In a deleted scene, the actress who played the hero's sister, Ruth Landshoff, was featured in this scene, where she was running along a beach fleeing from the vampire. That scene is not in any version or restoration of the film, nor in the original script). When Hutter revives her, she sends him to fetch Professor Bulwer. After he leaves, Orlok comes in. He becomes so engrossed drinking her blood that he forgets about the coming day. When a rooster crows, Orlok vanishes in a puff of smoke as he tries to flee. Ellen lives just long enough to be embraced by her grief-stricken husband. The last scene shows Count Orlok's ruined castle in the Carpathian Mountains, symbolizing the end of his reign of terror.

Cast

- Max Schreck as Count Orlok

- Gustav von Wangenheim as Thomas Hutter

- Greta Schröder as Ellen Hutter

- Alexander Granach as Knock

- Georg H. Schnell as Shipowner Harding

- Ruth Landshoff as Annie

- John Gottowt as Professor Bulwer

- Gustav Botz as Professor Sievers

- Max Nemetz as The Captain of The Empusa

- Wolfgang Heinz as First Mate of The Empusa

- Hardy von Francois as mental hospital doctor

- Albert Venohr as sailor two

- Guido Herzfeld as innkeeper

- Karl Etlinger as student with Bulwer

- Fanny Schreck as hospital nurse

Production

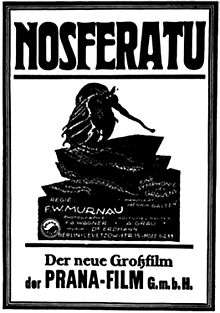

The studio behind Nosferatu, Prana Film, was a short-lived silent-era German film studio founded in 1921 by Enrico Dieckmann and occultist-artist Albin Grau, named for the Hindu concept of prana. Although the studio's intent was to produce occult- and supernatural-themed films, Nosferatu was its only production,[3] as it declared bankruptcy in order to dodge copyright infringement suits from Bram Stoker's widow Florence Balcombe.

Grau had had the idea to shoot a vampire film, the inspiration of which had risen from a war experience: in the winter of 1916, a Serbian farmer told him that his father was a vampire and one of the undead.[4]

Diekmann and Grau gave Henrik Galeen, a disciple of Hanns Heinz Ewers, the task to write a screenplay inspired by Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula, despite Prana Film not having obtained the film rights. Galeen was an experienced specialist in dark romanticism; he had already worked on Der Student von Prag (The Student of Prague) in 1913, and the screenplay for Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (The Golem: How He Came into the World) (1920). Galeen set the story in the north German harbour town of Wismar (where part of the film was shot) under the name Wisborg that the city took when it passed under Swedish rule after the Thirty Year's War. He changed the character's names and added the idea of the vampire bringing the plague to Wisborg via rats on the ship, and left out the Van Helsing vampire hunter character. Galeen's Expressionist style[5] screenplay was poetically rhythmic, without being so dismembered as other books influenced by literary Expressionism, such as those by Carl Mayer. Lotte Eisner described Galeen's screenplay as "voll Poesie, voll Rhythmus" ("full of poetry, full of rhythm").[6]

Filming began in July 1921, with exterior shots in Wismar. A take from Marienkirche's tower over Wismar marketplace with the Wasserkunst Wismar served as the establishing shot for the Wisborg scene. Other locations were the Wassertor, the Heiligen-Geist-Kirche yard and the harbour. In Lübeck, the abandoned Salzspeicher served as Nosferatu's new Wisborg house, the one of the churchyard of the Aegidienkirche served as Hutter's, and down the Depenau a procession of coffin bearers bore coffins of supposed plague victims. Many scenes of Lübeck appear in the hunt for Knock, who ordered Hutter in the Yard of Füchting to meet Count Orlok. Further exterior shots followed in Lauenburg, Rostock and on Sylt. The exteriors of the film set in Transylvania were actually shot on location in northern Slovakia, including the High Tatras, Vrátna Valley, Orava Castle, the Váh River, and Starhrad.[7] The team filmed interior shots at the JOFA studio in Berlin's Johannisthal locality and further exteriors in the Tegel Forest.

For cost reasons, cameraman Fritz Arno Wagner only had one camera available, and therefore there was only one original negative.[8] The director followed Galeen's screenplay carefully, following handwritten instructions on camera positioning, lighting, and related matters.[6] Nevertheless, Murnau completely rewrote 12 pages of the script, as Galeen's text was missing from the director's working script. This concerned the last scene of the film, in which Ellen sacrifices herself and the vampire dies in the first rays of the Sun.[9][10] Murnau prepared carefully; there were sketches that were to correspond exactly to each filmed scene, and he used a metronome to control the pace of the acting.[11]

Music

The original score was composed by Hans Erdmann to be performed by an orchestra during the projection. It is also said that the original music was recorded during a screening of the film. However, most of the score has been lost, and what remains is only a reconstitution of the score as it was played in 1922. Thus, throughout the history of Nosferatu screenings, many composers and musicians have written or improvised their own soundtrack to accompany the film. For example, James Bernard, composer of the soundtracks of many Hammer horror films in the late 1950s and 1960s, has written a score for a reissue.[12]

Deviations from the novel

The story of Nosferatu is similar to that of Dracula and retains the core characters—Jonathan and Mina Harker, the Count, etc.—but omits many of the secondary players, such as Arthur and Quincey, and changes all of the characters' names – although in some recent releases of this film, which is now in the public domain in the United States but not in most European countries, the written dialogue screens have been changed to use the Dracula versions of the names. The setting has been transferred from Britain in the 1890s to Germany in 1838.

In contrast to Dracula, Orlok does not create other vampires, but kills his victims, causing the townfolk to blame the plague, which ravages the city. Also, Orlok must sleep by day, as sunlight would kill him, while the original Dracula is only weakened by sunlight. The ending is also substantially different from that of Dracula. The count is ultimately destroyed at sunrise when the "Mina" character sacrifices herself to him. The town called "Wisborg" in the film is in fact a mix of Wismar and Lübeck; in other versions of the film, the name of the city had been changed, for unknown reasons, back to "Bremen".[13]

Release

Shortly before the premiere, an advertisement campaign was placed in issue 21 of the magazine Bühne und Film, with a summary, scene and work photographs, production reports, and essays, including a treatment on vampirism by Albin Grau.[14] Nosferatu's preview premiered on 4 March 1922 in the Marmorsaal of the Berlin Zoological Garden. This was planned as a large society evening entitled Das Fest des Nosferatu (Festival of Nosferatu), and guests were asked to arrive dressed in Biedermeier costume. The cinema premiere itself took place on 15 March 1922 at Berlin's Primus-Palast.

In the 1930s sound version, Die zwölfte Stunde – Eine Nacht des Grauens (The Twelfth Hour: A Night of Horror), which is less commonly known, was a completely unauthorised and re-edited version of the film that was released in Vienna (capital of Austria), on May 16, 1930, with sound-on-disc accompaniment, with a recomposition of Hans Erdmann's original score (by Georg Fiebiger, born 22. June 1901 in Breslau, died in 1950 ) was a German production manager and composer of film music. But however, with sound effects only. It had an alternate ending that was much happier than the original, the characters were all renamed again, this time Count Orlok's name was changed to Prince Wolkoff, Knock became Karsten, Hutter and Ellen became Kundberg and Margitta, and Lucy being changed to Maria. Apparently, Murnau had no part in this and obviously had no idea it was happening at the time. This version of the film, contained many scenes that were filmed by Murnau, but that were not shown at the original premiere and had been taken out before being seen by public audiences, 8 years earlier. It also contained additional footage not filmed by Murnau himself, instead by a cameraman Günther Krampf, under the direction of an unknown Dr. Waldemar Roger[15] (also known as Waldemar Ronger, died in 1958, who was a German film producer), who was said also to be a film editor and Lab Chemist, as well. One of these scenes added to the original scenes filmed for this film, on one occasion, in which an anonymous actor named Hans Behal (also known as Hans Behall, born 21 October 1893 in Vienna, Austria, and who later died in Israel in 1957) played the role of a priest and other folk-descriptives in a requiem scene. The name of the silent film director F. W. Murnau is no longer mentioned in the preamble.This version of (edited to approx. 80 min. for running time) was presented on June 5, 1981 at the French Cinematheque. In the recent 2012 restoration of the film, the Friedrich Wilheim Murnau Stiftung, claim that they have several copies of this version of the film.The film was originally banned completely in Sweden, however the ban was lifted after 20 years and has since been shown on television.[16]

Reception and legacy

Nosferatu brought Murnau into the public eye, especially since his film Der brennende Acker (The Burning Soil) was released a few days later. The press reported extensively on Nosferatu and its premiere. With the laudatory votes, there was also occasional criticism that the technical perfection and clarity of the images did not fit the horror theme. The Filmkurier of 6 March 1922 said that the vampire appeared too corporeal and brightly lit to appear genuinely scary. Hans Wollenberg described the film in photo-Stage No. 11 of 11 March 1922 as a "sensation" and praised Murnau's nature shots as "mood-creating elements."[17] In the Vossische Zeitung of 7 March 1922, Nosferatu was praised for its visual style.

This was the only Prana Film; the company declared bankruptcy after Stoker's estate, acting for his widow, Florence Stoker, sued for copyright infringement and won. The court ordered all existing prints of Nosferatu burned, but one purported print of the film had already been distributed around the world. This print was duplicated over the years, kept alive by a cult following, making it an example of an early cult film.[18]

The film has received overwhelmingly positive reviews. On Rotten Tomatoes it has a "Certified Fresh" label and holds a 97% "fresh" rating based on 62 reviews. The website's critical consensus reads, "One of the silent era's most influential masterpieces, Nosferatu's eerie, gothic feel—and a chilling performance from Max Schreck as the vampire—set the template for the horror films that followed."[19] It was ranked twenty-first in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" in 2010.[20] In 1997, critic Roger Ebert added Nosferatu to his list of The Great Movies, writing:

Here is the story of Dracula before it was buried alive in clichés, jokes, TV skits, cartoons and more than 30 other films. The film is in awe of its material. It seems to really believe in vampires. ... Is Murnau's "Nosferatu" scary in the modern sense? Not for me. I admire it more for its artistry and ideas, its atmosphere and images, than for its ability to manipulate my emotions like a skillful modern horror film. It knows none of the later tricks of the trade, like sudden threats that pop in from the side of the screen. But "Nosferatu" remains effective: It doesn’t scare us, but it haunts us.[21]

In popular culture

- The 1977 song "Nosferatu" from the album Spectres by American rock band Blue Öyster Cult is directly about the film.[22]

- In 1981, British rock band Queen and rock artist David Bowie recorded the song "Under Pressure".[23] For the music video, the band members were unavailable on tour; Director David Mallet edited together stock footage and various pieces from silent films of the 1920s, including scenes from Nosferatu.

- In 1989, French progressive rock outfit Art Zoyd released Nosferatu on Mantra Records. Thierry Zaboitzeff and Gérard Hourbette composed the pieces, to correspond with a truncated version of the film, then in circulation in the public domain.[24]

- The 1991 tabletop role-playing game Vampire: The Masquerade features a playable vampire clan known as "Nosferatu" whose monstrous appearances are often depicted similarly to Orlok's in official art.

- In 1995, Bernard J. Taylor adapted the story into the musical Nosferatu the Vampire.[25]

- The 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire, directed by E. Elias Merhige and written by Steven A. Katz, is a fictionalized account of the making of Nosferatu. It stars John Malkovich and Willem Dafoe.[26]

- An opera version composed by Alva Henderson in 2004, with libretto by Dana Gioia,[27] was released on CD in 2005, with Douglas Nagel as Count Orlok/Nosferatu, Susan Gundunas as Ellen Cutter (Ellen Hutter/Lucy Harker), Robert McPherson as Eric Cutter (Thomas Hutter/Jonathan Harker) and Dennis Rupp as Skuller (Knock/Renfield).

- In 2010, the Mallarme Chamber Players of Durham, North Carolina, commissioned composer Eric J. Schwartz to compose an experimental chamber music score for live performance alongside screenings of the film, which has since been performed a number of times.[28]

- On 28 October 2012, as part of the BBC Radio "Gothic Imagination" series, the film was reimagined on BBC Radio 3 as the radio play Midnight Cry of the Deathbird by Amanda Dalton directed by Susan Roberts, with Malcolm Raeburn playing the role of Graf Orlok (Count Dracula), Sophie Woolley as Ellen Hutter, Henry Devas as Thomas Hutter and Terence Mann as Knock.[29]

- In Rob Zombie's 2016 horror film 31, Doom-Head and Cherry Bomb, played by Richard Brake and Ginger Lynn, are engaging in rough sex while scenes from Nosferatu are playing on a small television screen.[30]

Remakes

A remake by director Werner Herzog, Nosferatu the Vampyre, starred Klaus Kinski (as Count Dracula, not Orlok), and was released in 1979.[31]

A planned "remix" (remake) by director David Lee Fisher, has been in development after being successfully funded on Kickstarter on December 3, 2014.[32] On April 13, 2016, it was reported that Doug Jones had been cast as Count Orlok in the film and the filming had begun. The film will use green screen to insert colorized backgrounds from the original film atop live-action, a process Fisher previously used for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.[33]

On July 29, 2015, it was reported that a remake of the film would be written and directed by The Witch director Robert Eggers, and produced by Jay Van Noy and Lars Knudsen.[34] On November 12, 2016, Eggers reaffirmed the film as his next project.[35]

Getty Images released a version layered with sound, music and voices from their sound effects library. The version shows the various layers of sound as one watches the original film. It can be found at http://nonsilentfilm.com/en/

See also

- List of films in the public domain in the United States

- List of German films 1919–1933

- Gothic film

- Vampire film

References

Notes

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "What's the Big Deal?: Nosferatu (1922)". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Elsaesser, Thomas (February 2001). "Six Degrees Of Nosferatu". Sight and Sound. ISSN 0037-4806. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Mückenberger, Christiane (1993), "Nosferatu", in Dahlke, Günther; Karl, Günter, Deutsche Spielfilme von den Anfängen bis 1933 (in German), Berlin: Henschel Verlag, p. 71, ISBN 3-89487-009-5

- ↑ Roger Manvell, Henrik Galeen - Films as writer:, Other films:, Film Reference, retrieved 23 April 2009

- 1 2 Eisner 1967 page 27

- ↑ Votruba, Martin. "Nosferatu (1922) Slovak Locations". Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh.

- ↑ Prinzler page 222: Luciano Berriatúa and Camille Blot in section: Zur Überlieferung der Filme. Then it was usual to use at least two cameras in parallel to maximize the number of copies for distribution. One negative would serve for local use and another for foreign distribution.

- ↑ Eisner 1967 page 28 Since vampires dying in daylight appears neither in Stoker's work nor in Galeen's script, this concept has been solely attributed to Murnau.

- ↑ Michael Koller (July 2000), "Nosferatu", Issue 8, July–Aug 2000, senses of cinema, retrieved 23 April 2009

- ↑ Grafe page 117

- ↑ Randall D. Larson (1996). "An Interview with James Bernard" Soundtrack Magazine. Vol 15, No 58, cited in Randall D. Larson (2008). "James Bernard's Nosferatu". Retrieved on 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Ashbury, Roy (5 November 2001), Nosferatu (1st ed.), Pearson Education, p. 41

- ↑ Eisner page 60

- ↑ "Waldemar Ronger | filmportal.de". www.filmportal.de. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- ↑ "Nosferatu Versionen - Grabstein für Max Schreck". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- ↑ Hans Helmut Prinzler (ed.): Murnau – Ein Melancholiker des Films. Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek. Bertz, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-929470-25-X, p. 129.

- ↑ Hall, Phil. "THE BOOTLEG FILES: "NOSFERATU"". Film Threat. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror (Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens) (Nosferatu the Vampire) (1922)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema: 21 Nosferatu". Empire.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (28 September 1997). "Nosferatu Movie Review & Film Summary (1922)". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ "17 Fear-Filled Songs Inspired by Scary Movies". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "The Case for David Bowie as Music Video King". Pitchfork Media. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Kozinn, Alan (23 July 1991). "Music in Review". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "Bernard J. Taylor". AllMusic. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Scott, A. O. (29 December 2000). "FILM REVIEW; Son of 'Nosferatu,' With a Real-Life Monster". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Alva Henderson - MagCloud". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "Pfeiffer presents classic 'Nosferatu'". The Stanly News and Press. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "Midnight Cry of the Deathbird, Drama on 3 - BBC Radio 3". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ Dowd, A.A. (October 19, 2016). "Rob Zombie sends in the clowns with his abysmal death-match thriller 31". The A.V. Club. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

The film's juvenile, posturing nihilism finds flesh-and-blood embodiment in the character of Doom-Head (Richard Brake), a hit man who screws to Nosferatu, applies his makeup to Beethoven, and quotes Karl Marx before a kill.

- ↑ Erickson, Hal. "Nosferatu the Vampyre". Allrovi. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ↑ "Thank you from Doug & David!". Kickstarter.com. 6 December 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "Doug Jones to Star in ‘Nosferatu’ Remake". Variety.com. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "NOSFERATU Remake in the Works with THE WITCH Director Robert Eggers". Collider.com. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "The Witch Director Confirms Nosferatu Remake Is His Next Film". Screenrant.com. 12 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Brill, Olaf, Film Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (GER 1922) (in German), retrieved 11 June 2009 (1921-1922 reports and reviews)

- Eisner, Lotte H. (1967), Murnau. Der Klassiker des deutschen Films (in German), Velber/Hannover: Friedrich Verlag

- Eisner, Lotte H. (1980), Hoffmann, Hilmar; Schobert, Walter, eds., Die dämonische Leinwand (in German), Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, ISBN 3-596-23660-6

- Grafe, Frieda (2003), Enno Patalas, ed., Licht aus Berlin: Lang/Lubitsch/Murnau (in German), Berlin: Verlag Brinkmann & Bose, ISBN 978-3922660811

- Meßlinger, Karin; Thomas, Vera (2003), "Nosferatu", in Hans Helmut Prinzler, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: ein Melancholiker des Films (in German), Berlin: Bertz Verlag GbR, ISBN 3-929470-25-X

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nosferatu |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nosferatu. |

- Nosferatu: The Ultimate Blu-ray and DVD Guide Comprehensive article detailing the film's history, different versions and every release of the restorations worldwide

- Nosferatu on IMDb

- Nosferatu at Rotten Tomatoes

- Nosferatu is available for free download at the Internet Archive (alternative link)