Northwest Ordinance

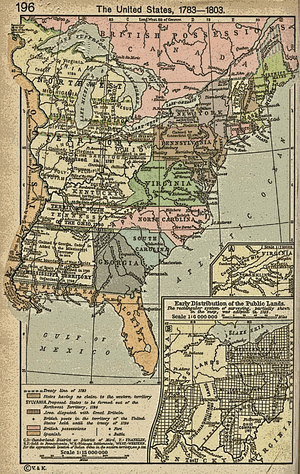

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio, and also known as The Ordinance of 1787) was an act of the Congress of the Confederation of the United States (the Confederation Congress), passed July 13, 1787. The ordinance created the Northwest Territory, the first organized territory of the United States, from lands beyond the Appalachian Mountains, between British North America and the Great Lakes to the north and the Ohio River to the south. The upper Mississippi River formed the Territory's western boundary. It was the response to multiple pressures: the westward expansion of American settlers, tense diplomatic relations with Great Britain and Spain, violent confrontations with Native Americans, the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, and the empty treasury of the American government. It was based upon, but more conservative than Thomas Jefferson's proposed ordinance of 1784. The 1787 law relied on a strong central government, which was assured under the new Constitution that took effect in 1789. In August 1789, it was replaced by the Northwest Ordinance of 1789, in which the new Congress reaffirmed the Ordinance with slight modifications.[1]

Considered one of the most important legislative acts of the Confederation Congress,[2] it established the precedent by which the Federal government would be sovereign and expand westward with the admission of new states, rather than with the expansion of existing states and their established sovereignty under the Articles of Confederation. It also set legislative precedent with regard to American public domain lands.[3] The U.S. Supreme Court recognized the authority of the Northwest Ordinance of 1789 within the applicable Northwest Territory as constitutional in Strader v. Graham, 51 U.S. 82, 96, 97 (1851), but did not extend the Ordinance to cover the respective states once they were admitted to the Union.[4]

The prohibition of slavery in the territory had the practical effect of establishing the Ohio River as the boundary between free and slave territory in the region between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. This division helped set the stage for national competition over admitting free and slave states, the basis of a critical question in American politics in the 19th century until the Civil War.

Context and history

The territory was acquired by Great Britain from France following victory in the Seven Years' War and the 1763 Treaty of Paris. Great Britain took over the Ohio Country, as its eastern portion was known, but a few months later closed it to new European settlement by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The Crown tried to restrict settlement of the thirteen colonies between the Appalachians and the Atlantic, which raised colonial tensions among those who wanted to move west. With the colonials' victory in the American Revolutionary War and signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the United States claimed the territory, as well as the areas south of the Ohio. The territories were subject to overlapping and conflicting claims of the states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Virginia dating from their colonial past. The British were active in some of the border area until after the Louisiana Purchase and the War of 1812.

The region had long been desired for expansion by colonists. The states were encouraged to settle their claims by the US government's de facto opening of the area to settlement following the defeat of Great Britain. In 1784, Thomas Jefferson, a delegate from Virginia, proposed that the states should relinquish their particular claims to all the territory west of the Appalachians, and the area should be divided into new states of the Union. Jefferson's proposal to create a federal domain through state cessions of western lands was derived from earlier proposals dating back to 1776 and debates about the Articles of Confederation.[5] Jefferson proposed creating ten roughly rectangular states from the territory, and suggested names for the new states: Cherronesus, Sylvania, Assenisipia, Illinoia, Metropotamia, Polypotamia, Pelisipia, Washington, Michigania and Saratoga.[6] The Congress of the Confederation modified the proposal, passing it as the Land Ordinance of 1784. This ordinance established the example that would become the basis for the Northwest Ordinance three years later.

The 1784 ordinance was criticized by George Washington in 1785 and James Monroe in 1786. Monroe convinced Congress to reconsider the proposed state boundaries; a review committee recommended repealing that part of the ordinance. Other politicians questioned the 1784 ordinance's plan for organizing governments in new states, and worried that the new states' relatively small sizes would undermine the original states' power in Congress. Other events such as the reluctance of states south of the Ohio River to cede their western claims resulted in a narrowed geographic focus.[5]

When passed in New York in 1787, the Northwest Ordinance showed the influence of Jefferson. It called for dividing the territory into gridded townships, so that once the lands were surveyed, they could be sold to individuals and speculative land companies. This would provide both a new source of federal government revenue and an orderly pattern for future settlement.[7]

Effects of the legislation

Established legal basis of land ownership

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established the concept of fee simple ownership, by which ownership was in perpetuity with unlimited power to sell or give it away. This was called the "first guarantee of freedom of contract in the United States."[8]

Abolition and transfer of state claims

The passage of the ordinance, which ceded all unsettled lands to the federal government and established the public domain, followed the relinquishing of all such claims over the territory by the states. These territories were to be administered directly by Congress, with the intent of their eventual admission as newly created states. The legislation was revolutionary in that it established the precedent for new lands to be administered by the central government, albeit temporarily, rather than under the jurisdiction of the individually sovereign original states, as it was with the Articles of Confederation. The legislation also broke colonial precedent by defining future use of the natural navigation, transportation and communication routes; it did so in a way that anticipated future acquisitions beyond the Northwest Territories, and established federal policy.[9] Article 4 states: "The navigable waters leading into the Mississippi and St. Lawrence, and the carrying places between the same, shall be common highways and forever free, as well to the inhabitants of the said territory as to the citizens of the United States, and those of any other States that may be admitted into the confederacy, without any tax, impost, or duty therefor."

Admission of new states

The most significant intended purpose of this legislation was its mandate for the creation of new states from the region. It provided that at least three but not more than five states would be established in the territory, and that once such a state achieved a population of 60,000 it would be admitted into representation in the Continental Congress on an equal footing with the original thirteen states. The first state created from the Northwest Territory was Ohio, in 1803, at which time the remainder was renamed Indiana Territory. The other four states were Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. A portion (about a third) of what later became the state of Minnesota was also part of the territory.

Education

The ordinance of Congress called for a public university as part of the settlement and eventual statehood of the Ohio Territory, further stipulating "Religion, morality and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged." In 1786, Manasseh Cutler became interested in the settlement of western lands by American pioneers to the Northwest Territory. The following year, as agent of the Ohio Company of Associates that he had been involved in creating, he organized a contract with Congress whereby his associates (former soldiers of the Revolutionary War) might purchase one and a half million acres (6,000 km²) of land at the mouth of the Muskingum River with their Certificate of Indebtedness. Cutler also took a leading part in drafting the Ordinance of 1787 for the government of the Northwest Territory, which was finally presented to Congress by Massachusetts delegate Nathan Dane. To smooth passage of the Northwest Ordinance, Cutler bribed key congressmen by making them partners in his land company. By changing the office of provisional governor from an elected to an appointed position, Cutler was able to offer the position to the president of Congress, Arthur St. Clair.[10] In 1797, settlers from Marietta traveled upstream via the Hocking River to establish a location for the school, choosing Athens due to its location directly between Chillicothe (the original capital of Ohio) and Marietta. Originally named in 1802 as the American Western University, the school never opened. Instead, Ohio University was formally established on February 18, 1804, when its charter was approved by the Ohio General Assembly. Its establishment came 11 months after Ohio was admitted to the Union. The first three students enrolled in 1809. Ohio University graduated two students with bachelor's degrees in 1815.[11]

Establishment of territorial government

Before the population of a territory reached 5,000, there would be a limited form of government. There would be a governor, a secretary, and three judges, all appointed by Congress. The governor will have a "freehold estate therein, in one thousand acres of land,". The secretary and the judges will have a, "freehold estate therein, in five hundred acres of land". The governor would be commander-in-chief of the militia, appoint magistrates and other civil officers, and help create and publish laws as they see fit for their territory. They would have a three-year term. The secretary would be in charge of keeping and preserving the acts and laws passed by the territorial legislatures, the public records of the district and to transit authentic copies of such acts and proceedings every six months to the secretary of the Continental Congress. They would have a four-year term. The judges would be in charge will help the governor create and pass acts and laws and in making official court rulings. Their terms did not have a set time period. As soon as the population of a territory reached 5000 free, male inhabitants, then they would receive authority to elect representatives from their counties or townships for the general assembly. For every 500 free, males there would be one representative, until there were 25 representatives. Then the Congress will control the number and proportion of the representatives from that legislature. No male can be a representative unless they have been a citizen of the United States for at least three years or lived in the district for three years. In both cases the male in question would have to own at least 200 acres of land within the same district. These representatives shall serve for a term of two years. If a representative died or was removed from office, a new one would be elected to serve out the remainder time.

Establishment of natural rights

The natural rights provisions of the ordinance foreshadowed the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution.[12] Many of the concepts and guarantees of the Ordinance of 1787 were incorporated in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In the Northwest Territory, various legal and property rights were enshrined, religious tolerance was proclaimed, and it was enunciated that since "Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged." The right of habeas corpus was written into the charter, as was freedom of religious worship and bans on excessive fines and cruel and unusual punishment. Trial by jury and a ban on ex post facto laws were also rights recognized.

Prohibition of slavery

Art. 6. There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted: Provided, always, That any person escaping into the same, from whom labor or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original States, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service as aforesaid.[13]

The language of the ordinance prohibits slavery, but also contained a clear fugitive slave clause as well.[14] Efforts in the 1820s by pro-slavery forces to legalize slavery in two of the states created from the Northwest Territory failed, but an "indentured servant" law allowed some slaveholders to bring slaves under that status; they could not be bought or sold.[15][16] Southern states voted for the law because they did not want to compete with the territory over tobacco as a commodity crop; it was so labor-intensive that it was grown profitably only with slave labor. Additionally, slave-states' political power would merely be equalized, as there were three more slave-states than there were free-states in 1790.[17]

Effects on Native Americans

In two parts, the Northwest Ordinance mentions the Native Americans within this region. The first pertains to the demarcation of counties and townships out of lands that the Indians were regarded as having lost or relinquished title:

Section 8. For the prevention of crimes and injuries, the laws to be adopted or made shall have force in all parts of the district, and for the execution of process, criminal and civil, the governor shall make proper divisions thereof; and he shall proceed from time to time as circumstances may require, to lay out the parts of the district in which the Indian titles shall have been extinguished, into counties and townships, subject, however, to such alterations as may thereafter be made by the legislature.[18]

The second describes the preferred relationship with the Indians:

Article III. Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged. The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity, shall from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace and friendship with them.[19]

Many Native Americans in Ohio, who were not parties, refused to acknowledge treaties signed after the Revolutionary War that ceded lands north of the Ohio River inhabited by them to the United States. In a conflict sometimes known as the Northwest Indian War, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Little Turtle of the Miamis formed a confederation to stop white expropriation of the territory. After the Indian confederation had killed more than 800 soldiers in two battles — the worst defeats ever suffered by the U.S. at the hands of the Indians — President Washington assigned General Anthony Wayne command of a new army, which eventually defeated the confederation and thus allowed European-Americans to continue settling the territory.

Commemoration

Issue of 1937

On July 13, 1937, the U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp that commemorated the 150th anniversary of the North West Ordinance of 1787. The engraving on the stamp depicts a map of the United States at the time with the North West Territory between the figures of Manasseh Cutler (left) and Rufus Putnam.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Reginald Horsman, "The Northwest Ordinance and the Shaping of an Expanding Republic." Wisconsin Magazine of History (1989): 21-32 in JSTOR.

- ↑ "Northwest Ordinance". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Shōsuke Satō, History of the land question in the United States, Johns Hopkins University, (1886), p.352

- ↑ 51 U.S. 82, 96, 97

- 1 2 Hubbard, Bill, Jr. (2009). American Boundaries: the Nation, the States, the Rectangular Survey. University of Chicago Press. pp. 46–47, 114. ISBN 978-0-226-35591-7.

- ↑ "Report from the Committee for the Western Territory to the United States Congress". Envisaging the West: Thomas Jefferson and the Roots of Lewis and Clark. University of Nebraska–Lincoln and University of Virginia. March 1, 1784. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ↑ Jerel A. Rosati, James M. Scott, The Politics of United States Foreign Policy, Cengage Learning, 2010, p. 20

- ↑ De Soto, Hernando (2000). The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465016143.

- ↑ The Nation and its Water Resources, Leonard B. Dworsky, Division of Water Supply and Pollution Control, United States Public Health Service, 167pp., 1962. Chapters 1-6

- ↑ McDougall, Walter A. Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History, 1585–1828. (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), p. 289.

- ↑ "Ohio University". Ohio History Central: An Online Encyclopedia of Ohio History. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ↑ Chardavoyne, David G. (2006). "The Northwest Ordinance and Michigan's Territorial Heritage". In Finkelman, Paul; Hershock, Martin J. The history of Michigan law. Ohio University Press series on law, society, and politics in the Midwest. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1661-7. OCLC 65205057. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

Its provisions established a structure of government that encouraged settlement of that vast region and provided those settlers a startling set of civil rights that presaged the U.S. Constitution's Bill of Rights

- ↑ "Northwest Ordinance; July 13, 1787". Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ↑ Paul Finkelman, "Slavery and the Northwest Ordinance: A Study in Ambiguity", Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Winter 1986)|, pp. 345

- ↑ David Brion Davis and Steven Mintz, The Boisterous Sea of Liberty, 2000 p. 234

- ↑ Paul Finkelman, "Evading the Ordinance: The Persistence of Bondage in Indiana and Illinois", , Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 1989, p. 21

- ↑ Marcus D. Pohlmann, Linda Vallar Whisenhunt, Student's Guide to Landmark Congressional Laws on Civil Rights, Greenwood Press, 2002, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Transcript of the Northwest Ordinance – 1787. An Ordinance for the government of the Territory of the United States northwest of the River Ohio. Section 8. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ↑ Transcript of the Northwest Ordinance – 1787. An Ordinance for the government of the Territory of the United States northwest of the River Ohio. Section 14, Article 3. Retrieved March 21, 2014

- ↑ "Ordinance of 1787 Sesquicentennial Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

Further reading

- Berkhofer Jr, Robert F. "The Northwest Ordinance and the Principle of Territorial Evolution." in The American Territorial System (Athens, Ohio, 1973) pp: 45-55.

- Duffey, Denis P. "The Northwest Ordinance as a Constitutional Document." Columbia Law Review (1995): 929-968. in JSTOR

- Horsman, Reginald. "The Northwest Ordinance and the Shaping of an Expanding Republic." Wisconsin Magazine of History (1989): 21-32. in JSTOR

- Hyman, Harold M. American Singularity: The 1787 Northwest Ordinance, the 1862 Homestead and Morrill Acts, and the 1944 GI Bill (University of Georgia Press, 2008)

- Onuf, Peter S. Statehood and union: A history of the Northwest Ordinance (Indiana University Press, 1987)

- Williams, Frederick D., ed. The Northwest Ordinance: Essays on Its Formulation, Provisions, and Legacy (Michigan State U. Press, 2012)

External links

- Facsimile of 1789 Act

- "Turning Points: How the Ordinance of 1787 was drafted, by one of its authors", Wisconsin Historical Society

- Cyclopædia of Political Science, Political Economy, and the Political History of the United States by the Best American and European Writers. Lalor, John J., ed. New York: Maynard, Merrill, and Co., 1899. (First published 1881)

- Marcus D. Pohlmann, Linda Vallar Whisenhunt, Student's Guide to Landmark Congressional Laws on Civil Rights, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource: