Southern Netherlands

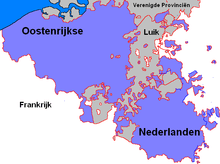

The Southern Netherlands,[lower-alpha 1] also called the Catholic Netherlands, was the part of the Low Countries largely controlled by Spain (1556–1714), later Austria (1714–94), and occupied then annexed by France (1794–1814). The region also included a number of smaller states that were never ruled by Spain or Austria: the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, the Imperial Abbey of Stavelot-Malmedy, the County of Bouillon, the County of Horne and the Princely Abbey of Thorn. The Southern Netherlands were part of the Holy Roman Empire until the whole area was annexed by Revolutionary France.

The Southern Netherlands comprised most of modern-day Belgium and Luxembourg, some parts of the Netherlands and Germany (the region of Upper-Gueldres, now divided between Germany and the modern Dutch Province of Limburg and in 1713 largely ceded to Prussia and the Bitburg area in Germany, then part of Luxembourg) as well as, until 1678, most of the present Nord-Pas-de-Calais region and the Longwy area in northern France.

Place in the broader Netherlands

As they were very wealthy, the Netherlands in general were an important territory of the Habsburg crown which also ruled Spain and Austria among other places. But unlike the other Habsburg dominions, they were led by a merchant class. It was the merchant economy which made them wealthy, and the Habsburg attempts at increasing taxation to finance their wars[lower-alpha 2] was a major factor in their defence of their privileges. This, together with resistance to penal laws enforced by the Habsburg monarchy that made heresy a capital crime, led to a general rebellion of the Netherlands against Habsburg rule in the 1570s. Although the northern seven provinces, led by Holland and Zeeland, established their independence as the United Provinces after 1581, the ten southern Netherlands were reconquered by the Spanish general Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma. Liège, Stavelot-Malmédy and Bouillon maintained their independence.

The Habsburg Netherlands, passed to the Austrian Habsburgs after the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714. Under Austrian rule, the ten provinces' defence of their privileges proved as troublesome to the reforming Emperor Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor as it had to his ancestor Philip II two centuries before, leading to a major rebellion in 1789–1790. The Austrian Netherlands were ultimately lost to the French Revolutionary armies, and annexed to France in 1794. Following the war, Austria's loss of the territories was confirmed, and they were joined with the northern Netherlands as a single kingdom under the House of Orange at the 1815 Congress of Vienna. The southeastern third of Luxembourg Province was made into the autonomous Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, because it was claimed by both the Netherlands and Prussia.

In 1830 the predominantly Roman Catholic southern half became independent as the Kingdom of Belgium (the northern half being predominantly Calvinist). In 1839 the final border between the kingdom of the Netherlands and Belgium was determined and the eastern part of Limburg returned to the Netherlands as the province of Limburg. The autonomy of Luxembourg was recognised in 1839, but an instrument to that effect was not signed until 1867. The King of the Netherlands was Grand Duke of Luxembourg until 1890, when William III was succeeded by his daughter, Wilhelmina of the Netherlands – but Luxembourg still followed the Salic law at the time, which forbade a woman to rule in her own right, so the union of the Dutch and Luxembourger crowns then ended. The northwestern two-thirds of the original Luxembourg remains a province of Belgium.

Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden, Spanish: Países Bajos españoles) was a portion of the Low Countries controlled by Spain from 1556 to 1714, inherited from the Dukes of Burgundy. Although the territory of the Duchy of Burgundy itself remained in the hands of France, the Habsburgs remained in control of the title of Duke of Burgundy and the other parts of the Burgundian inheritance, notably the Low Countries and the Free County of Burgundy in the Holy Roman Empire. They often used the term Burgundy to refer to it (e.g. in the name of the Imperial Circle it was grouped into), until 1794, when the Austrian Netherlands were lost to the French Republic.

When part of the Netherlands separated from Spanish rule and became the United Provinces in 1581 the remainder of the area became known as the Spanish Netherlands and remained under Spanish control. This region comprised modern Belgium, Luxembourg as well as part of northern France.

The Spanish Netherlands originally consisted of:

- County of Flanders, including Walloon Flanders

- County of Artois

- City of Tournai

- Cambrai (roughly the département Nord and the northern half of Pas-de-Calais in modern France)

- Duchy of Luxembourg

- Duchy of Limburg

- County of Hainaut

- County of Namur

- Lordship of Mechelen[lower-alpha 3] (officially a county since 1490)

- Duchy of Brabant, including the Margraviate of Antwerp

- the Upper Quarter (Bovenkwartier) of the duchy of Guelders (around Venlo and Roermond, in the present province of Dutch Limburg, and the town of Geldern in the present German district Kleve)

The capital, Brussels, was in Brabant. In the early 17th century, there was a flourishing court at Brussels, which was under the government of King Philip III's half-sister Archduchess Isabella and her husband, Archduke Albert of Austria. Among the artists who emerged from the court of the "Archdukes", as they were known, was Peter Paul Rubens. Under the Archdukes, the Spanish Netherlands actually had formal independence from Spain, but always remained unofficially within the Spanish sphere of influence, and with Albert's death in 1621 they returned to formal Spanish control, although the childless Isabella remained on as Governor until her death in 1633.

The failing wars intended to regain the 'heretical' northern Netherlands meant significant loss of (still mainly Catholic) territories in the north, which was consolidated in 1648 in the Peace of Westphalia, and given the peculiar, inferior status of Generality Lands (jointly ruled by the United Republic, not admitted as member provinces): Zeeuws-Vlaanderen (south of the river Scheldt), the present Dutch province of Noord-Brabant and Maastricht (in the present Dutch province of Limburg).

As Spanish power waned in the latter decades of the 17th century, the territory of the Spanish Netherlands was repeatedly invaded by the French and an increasing portion of the territory came under French control in successive wars. By the Treaty of the Pyrenees of 1659 the French annexed Artois and Cambrai, and Dunkirk was ceded to the English. By the Treaties of Aix-la-Chapelle (ending the War of Devolution in 1668) and Nijmegen (ending the Franco-Dutch War in 1678), further territory up to the current Franco-Belgian border was ceded, including Walloon Flanders (the area around Lille, Douai and Orchies), as well as half of the county of Hainaut (including Valenciennes). Later, in the War of the Reunions and the Nine Years' War, France annexed other parts of the region.

Austrian Netherlands

Under the Treaty of Rastatt (1714), following the War of the Spanish Succession, what was left of the Spanish Netherlands was ceded to Austria and thus became known as the Austrian Netherlands or Belgium Austriacum. However, the Austrians themselves generally had little interest in the region (aside from a short-lived attempt by Emperor Charles VI to compete with British and Dutch trade through the Ostend Company), and the fortresses along the border (the Barrier Fortresses) were, by treaty, garrisoned with Dutch troops. The area had, in fact, been given to Austria largely at British and Dutch insistence, as these powers feared potential French domination of the region.

Throughout the latter part of the eighteenth century, the principal foreign policy goal of the Habsburg rulers was to exchange the Austrian Netherlands for Bavaria, which would round out Habsburg possessions in southern Germany. In the 1757 Treaty of Versailles, Austria agreed to the creation of an independent state in the Southern Netherlands ruled by Philip, Duke of Parma and garrisoned by French troops in exchange for French help in recovering Silesia. However the agreement was unimplemented and revoked by the Third Treaty of Versailles (1785) and Austrian rule continued.

In 1784 its ruler Emperor Joseph II did take up the long-standing grudge of Antwerp, whose once-flourishing trade was destroyed by the permanent closing of the Scheldt, and demanded that the Dutch Republic open the river to navigation. However, the Emperor's stance was far from militant, and he called off hostilities after the so-called Kettle War, known by that name because its only "casualty" was a kettle. Though Joseph did secure in the 1785 Treaty of Fontainebleau that the territory's rulers would be compensated by the Dutch Republic for the continued closing the Scheldt, this failed to gain him much popularity.

The people of the Austrian Netherlands rebelled against Austria in 1788 as a result of Joseph II's centralizing policies. The different provinces established the United States of Belgium (January 1790). However, waylaying Joseph's intended concessions to the Belgians to restore the height of their autonomy and privileges, Austrian imperial power was restored by Joseph's brother and successor, Leopold II by the end of 1790.

French annexation

In the course of the French Revolution, the entire region (including territories that were never under Habsburg rule, like the Bishopric of Liège) was overrun by French armies after they won the Battle of Sprimont in 1794. The territory was then annexed to the Republic (October 1, 1795).

Only a minority of the population - mostly the local Jacobins and other members of "Societies of Friends of Liberty and Equality" in urban areas - supported the annexation. The majority were hostile to the French regime, above all because of the imposition of the assignat, wholesale conscription, and the ferocious antireligious policies of the French revolutionaries. The opposition was first led by the Catholic clergy, which became an irreducible enemy of the French Republic after it dissolved convents and monasteries and confiscated ecclesiastical properties, ordered the separation of Church and State, shut down the University of Louvain and other Catholic educational institutions, regulated church attendance and introduced divorce. In 1797, nearly 8000 priests refused to swear the newly introduced Oath of Hatred of Kings ("serment de haine à la royauté"), and went into hiding to escape arrest and deportation. The situation, particularly in the religious field, eased with the rise to power of Bonaparte in 1799, but soon, the intensification of conscription, the police state and the Continental System, which brought ruin to Ostend and Antwerp, reignited opposition to French rule.[1] During that period Belgium was divided into ten départements: Deux-Nèthes, Dyle, Escaut, Forêts, Jemmape, Lys, Meuse-Inférieure, Ourthe, Roer and Sambre-et-Meuse.

Austria confirmed the loss of its territories by the Treaty of Campo Formio, in 1797.

In anticipation of Napoleon's defeat in 1814, it was hotly debated inside Austrian ruling circles whether Austria should get the Southern Netherlands back or, in view of the experience gained after the War of the Spanish Succession about the difficulty of defending non contiguous possessions, whether she should not instead obtain contiguous territorial compensations in Northern Italy.[2] This viewpoint won and the Congress of Vienna allotted the Southern Netherlands to the new United Kingdom of the Netherlands. After the Belgian Revolution of 1830, the region separated to become the independent Kingdom of Belgium.

See also

- History of Belgium

- List of Governors of the Habsburg Netherlands

- List of plenipotentiaries of Austrian Netherlands

- Seventeen Provinces

- Spanish Armada

- Union of Atrecht (Including map, 1579)

Notes

- ↑ (Dutch: Zuidelijke Nederlanden, Spanish: Países Bajos del Sur, French: Pays-Bas méridionaux)

- ↑ The example of these expensive wars which is best known to English-speaking people is that of the Spanish Armada. However, that came in 1588, a little after the Dutch had become exasperated to the extent of signing the Union of Utrecht in 1579.

- ↑ A seignory comes closest to the concept of a heerlijkheid; there is no equivalent in English for the Dutch-language term. In its earliest history, Mechelen was a heerlijkheid of the Bishopric (later Prince-Bishopric) of Liège that exercised its rights through the Chapter of Saint Rumbold though at the same time the Lords of Berthout and later the Dukes of Brabant also exercised or claimed separate feudal rights.

- ↑ Bitsch 1992, p. 73-75.

- ↑ Kann 1974, pp. 229-230.

References

- Bitsch, Marie-Thérèse (1992), Histoire de la Belgique (in French), Hatier, pp. 73–75

- Kann, Robert A. (1974), A History of the Habsburg Empire 1526-1918, University of California Press, pp. 229–230

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Southern Netherlands. |

- Blom, J. C. H. and E. Lamberts, eds. History of the Low Countries (2006) 504pp excerpt and text search; also complete edition online

- Cammaerts, Émile. A History of Belgium from the Roman Invasion to the Present Day (1921) 357 pages; complete text online

- Cook, Bernard A. Belgium: a history, 3rd ed. New York, 2004 ISBN 0-8204-5824-4

- Kossmann, E. H. The Low Countries 1780-1940 (1978) excerpt and text search