Northeast blackout of 1965

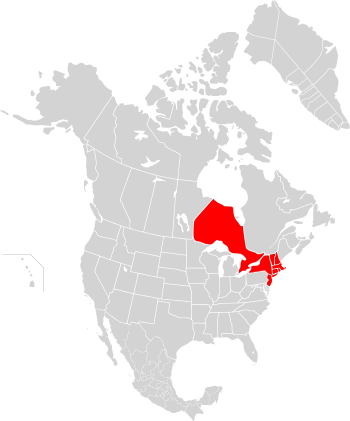

The Northeast blackout of 1965 was a significant disruption in the supply of electricity on Tuesday, November 9, 1965, affecting parts of Ontario in Canada and Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, and Vermont in the United States. Over 30 million people and 80,000 square miles (207,000 km2) were left without electricity for up to 13 hours.[1]

Cause

The cause of the failure was the setting of a protective relay on one of the transmission lines from the Sir Adam Beck Hydroelectric Power Station No. 2 in Queenston, Ontario, near Niagara Falls. The safety relay was set to trip if other protective equipment deeper within the Ontario Hydro system failed to operate properly. On a particularly cold November evening, power demands for heating, lighting, and cooking were pushing the electrical system to near its peak capacity. Transmission lines heading into Southern Ontario were heavily loaded. The system operators were not aware of a potential ambiguity between the extremely heavy power flows into Ontario and the setting upon which the relay was properly designed to operate. As a result of this ambiguity, at 5:16 p.m. Eastern Time, a small variation of power originating from the Robert Moses generating plant in Lewiston, New York caused the relay to trip, disabling a main power line heading into Southern Ontario. Instantly, the power that was flowing on the tripped line transferred to the other lines, causing them to become overloaded. Their own protective relays, which are also designed to protect the line from overload, tripped, isolating Beck Station from all of Southern Ontario.[2]

With no place else to go, the excess power from Beck Station then flowed east, over the interconnected lines into New York state, overloading them as well, and isolating the power generated in the Niagara region from the rest of the interconnected grid. The Beck generators, with no outlet for their power, were automatically shut down to prevent damage. The Robert Moses Niagara Power Plant continued to generate power, which supplied Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation customers in the metropolitan areas of Buffalo and Niagara Falls, New York. These areas ended up being isolated from the rest of the Northeast power grid and remained powered up. The Niagara Mohawk Western NY Huntley (Buffalo) and Dunkirk steam plants were knocked offline.[3] Within five minutes, the power distribution system in the Northeast was in chaos as the effects of overloads and the subsequent loss of generating capacity cascaded through the network, breaking the grid into "islands". Station after station experienced load imbalances and automatically shut down. The affected power areas were the Ontario Hydro System, St Lawrence-Oswego, Upstate New York, and New England. With only limited electrical connection southwards, power to the Southern States was not affected. The only part of the Ontario Hydro System not affected was the Fort Erie area next to Buffalo, which was still powered by older 25 Hz generators. Residents in Fort Erie were able to pick up a TV broadcast from New York, where a local backup generator was being used for transmission purposes.

Radio

An aircheck[4] of New York City radio station WABC from November 9, 1965 reveals disc jockey Dan Ingram doing a segment of his afternoon drive time show, during which he notes that a record he's playing (Jonathan King's "Everyone's Gone to the Moon") sounds slow, as do the subsequent jingles played during a commercial break. Ingram quipped that the King record "was in the key of R." The station's music playback equipment used motors that got their speed timing from the frequency of the powerline, normally 60 Hz. Comparisons of segments of the hit songs played at the time of the broadcast, minutes before the blackout happened, in this aircheck, as compared to the same song recordings played at normal speed reveal that approximately six minutes before blackout the line frequency was 56 Hz, and just two minutes before the blackout that frequency dropped to 51 Hz.[5] As Si Zentner's recording of "(Up a) Lazy River" plays in the background – again at a slower-than-normal tempo – Ingram mentions that the lights in the studio are dimming, then suggests that the electricity itself is slowing down, adding, "I didn't know that could happen". When the station's Action Central News report comes on at 5:25 pm ET, the staff remains oblivious to the impending blackout. The lead story is still Roger Allen LaPorte's self-immolation at United Nations Headquarters earlier that day to protest American military involvement in the Vietnam War; a taped sound bite with the attending physician plays noticeably slower and lower than usual. The newscast gradually fizzles out as power is lost by the time newscaster Bill Rice starts delivering the second story about New Jersey Senator Clifford P. Case's comments on his home state's recent gubernatorial election.

Unaffected areas

Some areas within the affected region were not blacked out. Municipal utilities in Hartford, Connecticut; Braintree, Holyoke, and Taunton, Massachusetts; and Fairport, Greenport, and Walden, New York had their own power plants, which operators disconnected from the grid and which were able to sustain local loads,[6] though some areas lost power for at least a few hours. Rochdale, Queens and Co-op City in The Bronx, New York were also unaffected as they had their own power plants.

Effect and aftermath

New York City was dark by 5:27 p.m. The blackout was not universal in the city; some neighborhoods, including the Midwood section of Brooklyn, never lost power. Also, some suburban areas, including Bergen County, New Jersey - served by PSE&G - did not lose power. Most of the television stations in the New York metro area were forced off the air, as well as about half the FM radio stations, as their common transmitter tower atop the Empire State Building lost power.

Fortunately, a bright full moon lit up the cloudless sky over the entire blackout area,[7] providing some aid for the millions who were suddenly plunged into darkness.

Power restoration was uneven. Most generators had no auxiliary power to use for startup. Parts of Brooklyn were repowered by 11:00pm, the rest of the borough by midnight. However, the entire city was not returned to normal power supply until nearly 7:00 a.m. the next day, November 10.

Power in western New York was restored in a few hours, thanks to the independent generating plant at Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York, which stayed online throughout the blackout. It provided auxiliary power to restart other generators in the area which, in turn, were used to get all generators in the blackout area going again.

The Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center saw the first full-scale activation of the facility during the blackout.[8][9]

The New York Times was able to produce a ten-page edition for November 10, using the printing presses of a nearby paper that was not affected, the Newark Evening News.[10] The front page showed a photograph of the city skyline with its lights all out.[11]

Following the blackout, measures were undertaken to try to prevent a repetition. Reliability councils were formed to establish standards, share information, and improve coordination amongst electricity providers. Ten councils were created covering the four networks of the North American Interconnected Systems. The Northeast Power Coordinating Council covered the area affected by the 1965 blackout.

The task force that investigated the blackout found that a lack of voltage and current monitoring was a contributing factor to the blackout, and recommended improvements.

The Electric Power Research Institute helped the electric power industry develop new metering and monitoring equipment and systems, which have become the modern SCADA systems in use today.

In contrast to the wave of looting and other incidents that took place during the 1977 New York City blackout, only five reports of looting were made in New York City after the 1965 blackout. It was said to be the lowest amount of crime on any night in the city's history since records were first kept.[12]

In popular culture

In literature

In Ira Levin's horror novel Rosemary's Baby (1967), Rosemary and her friend Hutch discuss the blackout when he visits her.

The blackout is dramatized in part 5 of Don DeLillo's novel Underworld (1997), in which one of the main characters makes his way back to his New York City hotel in the dark.

The blackout is mentioned in E.L. Doctorow's 2009 novel Homer & Langley. The Collyer brothers have welcomed several flower children into their home, and Homer, who is blind, is able to lead everyone through the overstuffed house in darkness outside to Central Park after the blackout hits.

In film

The film Where Were You When the Lights Went Out? (1968), starring Doris Day and Robert Morse, takes a comic view of the event.

In music

Tom Paxton wrote a song about the event, also titled "Where Were You When the Lights Went Out?", and performed it on the first episode of Pete Seeger's Rainbow Quest in November 1965.

The British heavy metal band Saxon wrote a song called 747 (Strangers in the Night) about a plane trying to land during the power outage.

In television

In the November 14, 1965 episode of What's My Line, Bennett Cerf asks Aurora, Colorado Mayor Norma Walker if she had anything to do with the blackout.

During Batman Season 1, episode 16, "He Meets His Match, The Grisly Ghoul" (ABC, March 3, 1966), the Joker mentions Gotham City having a power outage "just like New York".

At the end of Green Acres Season 1, episode 25, "Double Drick" (CBS, March 23, 1966), the blackout is theorized to have been caused when Mr. Douglas plugged an extension cord into the outlet at the top of a power pole, which was just installed by the inept employees of the local public utility.

In Bewitched Season 3, episode 9, "The Short Happy Circuit of Aunt Clara" (ABC, November 10, 1966), the blackout is caused when Aunt Clara casts a carelessly-worded spell while trying to move a piano. (The episode first aired just over one year after the blackout.)

CBS Playhouse Season 2, episode 4, "Shadow Game" (CBS, May 7, 1969), depicts a group of office workers trapped in their building during the blackout.

In the "Eyes" segment from the Night Gallery pilot film (NBC, November 8, 1969), Joan Crawford plays a wealthy and ruthless blind woman who blackmails a surgeon into performing an eye transplant so she can enjoy temporary sight, only to have the bandages from the operation come off just as the blackout hits.

In All in the Family Season 8, episode 10, "Archie and the KKK: Part 1" (CBS, November 27, 1977), the Bunkers are coping with a blackout. At one point Mike alludes to the supposed spike in New York's birthrate following the 1965 blackout (see "In urban legends", below).

During Quantum Leap Season 1, episode 6, "Double Identity - November 8, 1965" (NBC, April 21, 1989), the blackout is caused by a 1000 W hair dryer being plugged in. Al and Ziggy suggest that these events will allow Sam to leap.

In Dark Skies Season 1, episode 17, "To Prey in Darkness" (NBC, March 15, 1997), the blackout is caused by the aliens (ET's) to prevent the television broadcast of the 1947 Roswell, NM incident.

In Oz Season 1, episode 4, "Capital P" (HBO, July 28, 1997), the backstory of an inmate named Bob Rebadow details him being in the middle of being executed by means of the electric chair when the blackout occurred. As a result, his death sentence was commuted to life in prison.

During American Dreams Season 3, episode 8, "One in a Million" (NBC, November 14, 2004), the blackout occurs just before Beth goes into labor at home.[13]

Connections episode 1 ("The Trigger Effect") describes the outage.

In Wings Season 2, episode 4, "Sports and Leisure", During a game of Trivial Pursuit everyone discusses the blackout and where they were when it hit.

In urban legends

A thriving urban legend arose in the wake of the blackout, claiming that a peak in the birthrate of the blacked-out areas of New York City was observed nine months after the incident. The myth originated in a series of three articles published in The New York Times in August 1966, in which interviewed doctors mentioned that they had noticed an increased number of births.[14] The story was debunked in 1970 by J. Richard Udry, a demographer from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who did a careful statistical study that found no increase in the birthrate of the affected areas.[15]

In Theatre

In the musical "Fly By Night[16]" the great blackout of 1965 causes the death of the character Miriam and prevents the death of the character Mr.Mcclam.

UFO sightings during the blackout

When no cause for the blackout was immediately apparent, several writers (including John G. Fuller, in his book Incident at Exeter) postulated that the blackout was caused by UFOs. This may have been partially inspired by sightings of UFOs near Syracuse prior to the blackout.[17]

See also

- Brittle Power (1982 book)

- List of major power outages

- New York City blackout of 1977

- January 1998 North American ice storm

- Northeast blackout of 2003

References

- ↑ Burke, James (1985-12-17). "The Trigger Effect". Connections. Series 1. Episode 1. Event occurs at 15:30. BBC.

Over an area of 80 million square miles, 30 million people were now in darkness.

- ↑ Report of The Northeast Power co-ordinating Council (NPCC)

- ↑ Buffalo Evening News, November 10, 1965

- ↑ "MP3 of the broadcast as the blackout happened". WABC (AM) Music Radio 77. November 9, 1965. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Hear WABC DJ in NYC Talk Live On Air During Famous 1965 Northeast Blackout". That Eric Alper. October 16, 2015. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Providing Blackout Lights". Time Magazine. December 10, 1965.

- ↑ http://www.fullmoon.info/en/fullmoon-calendar/1965.html

- ↑ "Mount Weather / High Point Special Facility (SF) / Western Virginia Office of Controlled Conflict Operations - United States Nuclear Forces". fas.org. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- ↑ Keeny, L. Douglas (2002). The Doomsday Scenario. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. p. 16. ISBN 0-7603-1313-X.

- ↑ "The New York Times: Our History / 1965". nytco.com. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ↑ "Front page". The New York Times. November 10, 1965.

- ↑ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 14. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ↑ "American Dreams: One in a Million". TV.com. NBC. November 14, 2004.

- ↑ "From Here to Maternity". Snopes.com

- ↑ Udry, J. Richard (August 1970). "The Effect of the Great Blackout of 1965 on Births in New York City". Demography. 7 (3): 325. doi:10.2307/2060151.

- ↑ "Fly By Night". www.samuelfrench.com. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- ↑ NICAP's report of UFO Sightings during the Nov. 9, 1965 Blackout

Further reading

- Cave, Damien (October 15, 2001). "Imaginary infants as beacons of hope". Salon.com.

- Nye, David E. (2010). When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01374-1.

- Schewe, Phillip (2006). The Grid: A Journey Through the Heart of Our Electrified World. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10260-5.

- Sitts, George (December 1965). "Radio Pierces The Great Blackout". Broadcast Engineering.

External links

- Summers, Randy. "Memoirs of the 1965 Blackout". MemoryArchive.

- "The first episode of this BBC documentary series explained and re-enacted parts of the blackout". Connections. 1978. 'Video not available'

- "The Blackout of 1965 (NBC-TV coverage)". YouTube.

- "The 'Great Northeastern Blackout' of 1965". CBC Digital Archives.