Norse religion

Old Norse religion, alternately referred to as Norse paganism, is a scholarly term applied to the belief systems of Norse communities in the Viking Age. It was the framework of belief prior to the Christianization of Scandinavia, specifically during the Viking Age.

Old Norse religion arose from earlier belief systems practiced by linguistically Germanic tribes during the Iron Age. These were influenced by cultural interactions with other ethno-linguistic groups inhabiting Northern Europe.

Knowledge of Norse religion is mostly drawn from the results of archaeological field work, etymology and early written materials as it was largely a product of early practitioners who did not have a written history.

Terminology

Other terms used in some scholarly sources are "Norse paganism",[1] or "Nordic paganism".[2]

The scholar of Scandinavian studies Thomas A. DuBois focused on the belief systems of the Viking Age (800 to 1300) because this encompassed the period of Viking expansionism and the arrival and gradual conversion to Christianity.[3] DuBois expressed the view that Old Norse religion and other pre-Christian belief systems in Northern Europe must be viewed as "not as isolated, mutually exclusive language-bound entities, but as broad concepts shared across cultural and linguistic lines, conditioned by similar ecological factors and protracted economic and cultural ties."[4] During this period, the Norse interacted closely with other ethno-cultural and linguistic groups, such as the Sámi, Balto-Finns, Anglo-Saxons, Greenlandic Induit, and various speakers of Celtic and Slavic languages.[5] Economic, marital, and religious exchange occurred between the Norse and many of these other groups.[5]

Sources

The evidence that we have for Old Norse mythology is "incomplete and sketchy".[6]

Literary sources

— Medievalist Christopher Abram[7]

The pagans of Scandinavia did not leave any conventional written records discussing their religion.[8] They did have an alphabet, and some of the inscriptions appearing on material culture do mention the names of deities.[9] These inscriptions are brief and ambiguous.[10] A typical formation is "May Thor hallow this memorial", inscribed on the Virring Stone from Denmark.[10]

Old Norse poetry and sagas

The fullest records of Norse mythology survive in textual records recorded by Christians during the post-pagan period.[7] Prior to this, these narratives would have circulated in oral tradition, passed down verbally rather than in written form.[11] Old Norse poetry is generally divided into the skaldic and the eddic, although this is an artificial division and the two categories overlap.[11] The term "skaldic" is used to describe poetry designed for public performance at high-status gatherings like the royal court.[11] It takes its name from the Old Norse word skáld, which simply meant "poet".[11] Skaldic poetry was popular around the North Sea region in the late Viking Age, although continued to be produced into the Scandinavian Middle Ages, and witnessed a revival of popularity in thirteenth-century Iceland, at which point a number of these poems were written down.[11] References to Norse mythological elements appear in some skaldic poems, often through the form of kennings, although these typically only provide a single image from a myth, relying on the assumption that their audience would already be familiar with the mythological narrative.[12] Eddic poetry differs from skaldic poetry in providing fuller descriptions of myths.[1] The term "Eddic poetry" was developed in the seventeenth century in reference to two texts, the Prose Edda and Poetic Edda.[1] These texts were produced in the thirteenth century, during the high middle ages, and it is unclear how accurately they relate the mythological beliefs present in the pre-Christian period.[13] As part of an oral tradition, these poems and the myths that they contained would not have been static but would have evolved and developed over the centuries.[14]

Aside from the poetry is the Icelandic sagas, tales that often set during the island's pre-Christian past.[13] Although written from 12th century onward, The Saga of Icelanders for example recounts events set between the mid-ninth to mid-eleventh centuries, during which Iceland underwent Christianisation.[15] The Saga of Icelanders does not discuss any pre-Christian mythology, but does describe certain religious practices and attitudes.[16] However, there are several centuries dividing the composition of the Saga and the pre-Christian period in which it is set, and the authors' main motivation is to present an image of the past that suits their own designs, namely in glorifying their ancestors.[16] In his Ynglinga Saga, the Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson presented the pre-Christian deity Oðinn as a human being who, because he had supernatural abilities, was falsely worshipped as a god by his descendants.[17] Snorri'sEdda provides the fullest account of the myths as they were known to medieval Icelanders.[18] He wrote the text around 1225, with his intention being to assist readers in understanding the mythological references in skaldic poetry and to be able to compose their own skaldic poems.[19] Although cautious to insist that the myths that he was recounting were untrue, Snorri did not dismiss the pre-Christian gods as demons or condemn his ancestors for worshiping them, as other Christian authors would do.[20] Abram cautioned that Snorri's work "provides us with a fascinating long afterlife of myths beyond the conversion of Scandinavia to Christianity, but we can only use it as a guide to what pagans actually believed or thought, or what stories they told, if we exercise considerably caution".[21]

Other textual sources

Sources written by foreigners to Scandinavia, who wrote in languages other than Old Norse, also produced sources discussing pagan religion and mythology in Northern Europe.[21] The earliest of these sources is Germania, an ethnographic account of Germanic tribes written by the Roman historian Tacitus around 100 CE.[21] This is one of the only contemporary accounts discussing Scandinavia in the Iron Age, at a point when the belief systems were developing into Old Norse religion.[21] In the Middle Ages, a number of Christian commentators described the Norse belief system in languages other than Old Norse. As Christians, they were largely hostile to the pre-Christian beliefs, not fully understanding them, and often condemning them explicitly.[21] One of the best known examples of these accounts was Adam of Bremen's History of the Archbishops of Hampburg-Bremen, written between 1066 and 1072.[21] Here, Adam included an account of a pagan temple at Uppsala in Sweden, although had himself never been to the city and was relying on the accounts of others.[22] A century later, references to pagan myths and practices were included in History of the Danes by Saxo Grammaticus, an educated Danish Christian.[23]

Archaeological sources

The medievalist Christopher Abram noted that archaeology was of "irreplaceable value for the study of pagan religion" among the Norse.[24] Archaeological evidence is particularly useful for learning about Old Norse religion as it existed prior to the arrival of literacy,[24] and for learning about cultic sites and burials.[25] Unlike textual sources, it offers unmediated access to pre-Christian material, without having gone through the interpretations of Christian writers.[25] However, archaeological material can also be difficult to interpret; this is particularly the case when trying to understand the relationship between material artefacts and mythological systems.[25] Some pictorial evidence, most notably that of the picture stones, intersect with the mythologies recorded in later texts.[25] These picture stones, produced in mainland Scandinavia during the Viking Age, are the earliest known visual depictions of Norse mythological scenes.[10] It is nevertheless unclear what function these picture-stones had or what they meant to the communities who produced them.[10]

The Lindby image from Skåne in Sweden is often interpreted as Oðinn because it has an eye missing.[26] As noted by Abram, however, the Lindby image, like other figurines, is difficult to interpret with certainty; "it is impossible entirely to discount the mundane but unlikely possibility that the Lindby figurine represents to more than a man in a helmet, winking".[8]

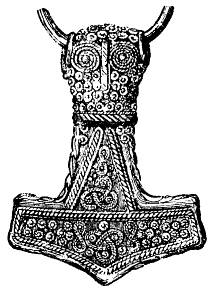

Textual sources do not connect Thor with the afterlife.[27] A bronze figurine found at Eyrarland, Iceland in 1817 has been interpreted as a depiction of Thor because it is believed to be holding a hammer.[27] The wide distribution of Mjöllnir pendants suggests that Thor was a particularly important and popular deity across Scandinavia in the Viking Age.[28] They are most commonly found in graves from modern Denmark, south-eastern Sweden, and southern Norway, but are found across the Viking world.[28] Abram noted that these pendants are "easily the most widespread religious symbol from the period".[29] Mjöllnir has typically been interpreted as a protective symbol, although may also have had associations with fertility.[28]

Place names

Place-names are an additional source of evidence for learning about Norse paganism.[30] Settlements bearing the name of a deity suggest that that god or goddess was important for the people living in that area.[30] Although it can be difficult to determine when a place-name first came into use, archaeological investigation can determine when a settlement first began.[30] The pattern of place-names suggests that there was much regional variation, with some gods appearing more popular in certain areas than others.[30] Some place-names contain elements indicating that they were sites of religious activity.[30] For instance, place name elements like -vé, -horg, and -hof can all be translated as 'temple' or 'sanctuary'.[30] In these instances, it is not easy to determine whether the place-name refers to a building or a non-built area of the landscape accorded religious uses.[30]

Historical development

Iron Age origins

Old Norse religion grew out of a "common religious-cultural heritage" spread across the linguistically Germanic societies of northwestern Europe.[31] Abram therefore described it as having "a genetic connection to the wider religious system of the Germanic Iron-Age tribes".[32]

Archaeological evidence is particularly important for understanding the religious belief systems and practices of these early periods.[33] According to Tacitus, the belief systems of the Iron Age Germanic tribes were polytheistic.[33] Tacitus interpreted these belief systems through a process of interpretatio romana, giving the Germanic deities the names of gods and goddesses whom his Roman readership would have been familiar with, such as Mercury, Hercules, Mars, and Isis.[34] He described a group of sub-tribes known as the Suebi, stating that they worshipped a goddess named Nerthus who was associated with the Earth.[35] The name "Nerthus" is phonetically similar to a god known as Njörðr who is recorded in later Old Norse sources.[35] One possibility is that at some point between when Tacitus wrote and the Viking Age, the female Nerthus was transformed into the male Njörðr in Scandinavian mythology.[36] An alternate possibility is that Nerthus and Njörðr were two separate deities in the Iron Age, but that knowledge of Nerthus had died out by the Viking Age.[36]

Tacitus described the existence of a distinct priestly caste among the Germanic tribes, who were believed to have direct access to the deities.[37] He portrayed sacrifice as a central facet of worship in this period, sometimes including human sacrifice.[37] Tacitus mentioned a temple that was part of Nerthus' cult, but elsewhere stated that the Germanic tribes did not "confine gods within walls" or produce anthropomorphic depictions of them, instead selecting woods and groves as their sacred places.[37] He also placed an emphasis on the practice of augury and fortune telling among these tribes.[37] There are no textual sources describing belief systems or religious practices among the Germanic tribes in the centuries following Tacitus.[38]

Viking Age expansion

In the latter decades of the ninth century, Scandinavian settlers arrived in Britain, bringing with them their own pre-Christian beliefs.[39] No cultic sites used by Scandinavian pagans have been archaeologically identified, although place names suggest some possible examples.[40] For instance, Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire was known as Othensberg in the twelfth century, a name which derived from the Old Norse Óðinsberg, or 'Hill of Óðin'.[41] A number of place-names also contain Old Norse references to mythological entities, such as alfr, skratii, and troll.[42] A number of pendants representing Mjolnir, the hammer of the god Thor, have also been found in England, reflecting the probability that he was worshipped among the Anglo-Scandinavian population.[43] Jesch argued that, given that there was only evidence for the worship of Odin and Thor in Anglo-Scandinavian England, these might have been the only deities to have been actively venerated by the Scandinavian settlers, even if they were aware of the mythological stories surrounding other Norse gods and goddesses.[44] The English church found itself in need of conducting a new conversion process to Christianise this incoming population.[45] It is not well understood how the Christian institutions converted these Scandinavian settlers, in part due to a lack of textual descriptions of this conversion process equivalent to Bede's description of the earlier Anglo-Saxon conversion.[46] However, it appears that the Scandinavian migrants had converted to Christianity within the first few decades of their arrival.[47]

The historian Judith Jesch suggested that these beliefs survived throughout Late Anglo-Saxon England not in the form of an active non-Christian religion, but as "cultural paganism", the acceptance of references to pre-Christian myths in particular cultural contexts within an officially Christian society.[48] Such "cultural paganism" could represent a reference to the cultural heritage of the Scandinavian population rather than their religious heritage.[49] For instance, many Norse mythological themes and motifs are present in the poetry composed for the court of Cnut the Great, an eleventh-century Anglo-Scandinavian king who had been baptised into Christianity and who otherwise emphasised his identity as a Christian monarch.[50]

Mythology

Mythological stories appear to have been widely known across the Old Norse world, as evidenced by their depiction on picture stones and their inclusion in poetry.[6] Precisely how these myths were transmitted is not known, although it was probably orally as a form of story telling, and in particular through the medium of poetry.[6]

Deities

Old Norse religion was polytheistic.[32] The range of gods known to Scandinavia varied over time.[51] The list of deities described in the high medieval textual sources differ from those produced in the Iron Age by Tacitus.[51] While there was apparently a common pantheon widely recognised across the Norse cultural area, individual communities aligned themselves to a particular god or goddess as a result of their regional location or socio-cultural priorities.[52] It may be that fertility gods like Freyr were more popular among groups who were subsistence farmers or farmers, whereas martial deities like Týr and Oðinn were more popular among warrior bands.[53]

The skaldic poetry contains a wide range of poetic names for Oðinn.[54] In the Ragnarsdrápa poem attributed to the poet Bragi Boddason and likely composed in the ninth century, a list of Oðinn's characteristics are alluded to, indicating the deity had strong associations with warfare.[54] For instance, Bragi Boddason refers to Oðinn as Hergautr ("army-god").[54] Bragi also associates Oðinn with the art of poetic composition itself, portraying poetry as a gift provided by Oðinn.[55]

There are poetic references to a goddess known as Rán, who is associated with the sea.[55]

Theophoric place-names

Various theophoric place names exist in the Scandinavian landscape, with places taking their names from those of pre-Christian deities.[51] Many more may have existed prior to the Christianisation of the region, with some place-names likely having been lost or replaced over the centuries.[56] The god Týr regularly appears in place-names in southern Scandinavia—particularly in present day Denmark—but is a far rarer toponymical element further north.[51] Similarly, the name of Oðinn appears with far greater regularity in the area of Denmark than in Norway, where Thor and Freyr are about twice as prevalent as Oðinn in place-names.[51] The god Ullinn is the most commonly found god in theophoric names in south-central and western Norway, but is not found elsewhere in Scandinavia.[51]

Not all of the deities who appear in the medieval textual sources also feature in the place-names: divinities who are absent include Loki, Baldr, Heimdallr, and Höðr.[51] This may be because these mythological characters did not have established cults at the time when place-names were established across Scandinavia.[51] Sometimes these deity names are combined with a term denoting a cult site; for instance, Odense in Denmark derives from "Oðinn's vé", strongly suggesting that it was a place where Oðinn was venerated.[30] Other place-names combine a deity name with an aspect of the natural landscape; examples include Frøslunda (Freyr's grove) and Torseke (Thor's oak grove), both in Sweden.[30] In these instances, it is unclear precisely what information was being conveyed by the place-name; perhaps it indicated that that was a place of worship, that the space had been specifically dedicated to a particular deity, or that a god or goddess was believed to specifically dwell there.[57]

Thor was also a popular element of personal names in Old Norse, both for men (e.g. Þórsteinn and Þórir) and women (e.g. Þórbjörg and Þórdís).[56] It proved particularly popular in Iceland, reflecting Thor's popularity in the Viking world's North Atlantic flank.[3] Thor's cult appears to have been particularly widespread, crossing various ethnic and social borders.[56]

Localized deities

Nordic peoples recognized a range of spirits dwelling in particular objects and places, such as trees, stones, waterfalls, lakes, houses, and small handmade idols. These localized deities would receive offerings from religious leaders through the use of a Staller (Norse-altar), which were placed among the forests and mountain sides which would be designated and restricted for certain deities.[58] These altars were seen as the only means in which to confirm receptiveness of the offerings by the leaders.

Localized deities played a significant role in religiously themed Nordic poems and sagas. In the poem Austrfararvísur (c. 1020), the Christian skald Sigvatr complains of not being able to get into any of the farms around the area of Sweden where he visits because of the diligent celebration of a sacrifice in honor of the elves.[59]

These localized deities also held the capacity of being a part of an intimate and personal relationship with the worshiper. It was very common for an individual to have their own personal guardian spirits who would receive personal offerings and relate to the individual's own dynamics.[60]

Agrarian deities

As agriculture developed in the Nordic communities so did the use of agricultural deities. As Norse life depended more and more on the factors that affected their crops, they began to dedicate more time to the deities that they believed had control over the weather, seasonal cycle, crops, and other agricultural aspects.[61] Gods such as Freyr were portrayed as having control over the weather and being a commander of fertility amongst the crops.

Although anthropomorphic in many respects, what is unique about these gods is the enhanced aspects of sexuality, reproduction, and fertility.[61] Not only do these gods have reign over the crops but they were also believed to have a profound effect on livestock, as they were often displayed with horns or animal fur.

A mainstay of Agrarian Deities is the use of magic for regeneration, which opens the door for other uses of magic. The Eddaic poem Völuspá portrays Vanir magic as a powerfully potent force used against the Æsir.[62]

Afterlife

Norse tradition had several fully developed ideas about death and the afterlife.[25] In mythological accounts, the deity most closely associated with death is Oðinn.[63] In particular, he is connected with death by hanging; this is apparent in Hávamál, a poem found in the Poetic Edda.[63] In stanza 138 of Hávamál, Oðinn describes his "auto-sacrifice", in which he hangs himself on Yggdrasill, the world tree for nine nights. This is done to attain wisdom and magical powers.[64] In the late Gautreks Saga, King Víkarr is hanged and then punctured by a spear; his executioner says "Now I give you to Oðinn."[64]

There is no archaeological evidence clearly alluding to a belief in Valhalla.[65]

In the Viking Age in particular, Norse people were often buried with a range of grave goods.[28] It is possible, although not certain, that these artefacts were intended to accompany the dead on a journey to the afterlife.[28]

“The dead could be inhumed in pits, wooden chambers, boats, or stone crists… Occasional very richly furnished graves were filled with objects, pots of food and drink and sacrificed animals, while others contained only the remains of the dead person’s dress” (Andrén).[66] These burial practices were unique to the nature of the Norse society as the sacrifice of animals for example is an offering to the Gods as the people in the society would on occasion perform ritualistic sacrifices to fend off evil. The sacrificing of the animals could be seen as a promise that the soul of the deceased will be guided and protected by the gods as they make their journey into a new spiritual life. Rather than going to Heaven or Hell, like in the Christian religion, the Norse believed in the dead going to different Gods. “Warriors who fell in battle were believed to end up with Odin in Valhalla or with Freyja at Folkvang. Those who drowned lived with the sea goddess Rán, while many who died of disease went to Hel” (Andrén).[66]

The use of ghost lore (referred to as Draugr) in the sagas is characteristic of the Norse lore and is directly connected to proper burial practices. Stories and references can be found throughout various sagas including the Laxdæla saga, Eirik's saga, and the Eyrbyggja saga. Ghosts are portrayed as menacing physical presences that intend to injure the living and haunt them.[67] The Laxdæla saga portray how hauntings often take a menacing and ill hearted turn. These accounts of hauntings and menacing ghosts are often solved through proper burial practices. Burial customs are the primary explanation and solution of the problems faced by ghosts.[68] In Eirik's Saga, Posteinn Eiriksson returns from death for a brief time to critique the handling of the dead.[69]

Cultic practice

In Norse paganism, myths may have been influenced by religious practices.[70]

Centers of worship

As few built temples have been archaeologically identified, some scholars believe that Old Norse religious activities largely took place outdoors.[71] This would parallel Tacitus' claim that the Iron Age Germanic tribes preferred to venerate their deities in groves and woods.[71]

Writing in the 11th century, Adam of Bremen claimed—through second hand sources—that there was a built temple at Uppsala, that it was "entirely decked out in gold", and that it contained statues of deities whom he called Thor, Wotan, and Frikko.[71] Adam also claimed that there was a large tree and a spring at Uppsala and that sacrifices were made at the latter.[72] Archaeologists have excavated at the Uppsala cult site searching for the features described by Adam; they found that the local Christian church was built atop an earlier hall, but that there was no archaeological evidence suggesting that this hall had a particular cultic function.[71] It may therefore be that any rituals taking place at Uppsala were carried out within a chieftain's hall rather than in a specially designated building.[71]

Archaeologists have also found evidence of other buildings that they have designated "cult houses", a term preferred over "temple".[72] One example comes from Borg in Östergötland, Sweden. This building has been interpreted as a "cult house" because several Mjöllnir pendants and a particularly high concentration of dog and pig bones had been buried outside it.[72] Another example comes from Lunda in Södermanland, again in Sweden. Here, three figurines were found in and around the building; two featured erect phalluses—perhaps representing a fertility god like Freyr—and the other a hanged man.[72]

Ancestor worship

Devotion to deceased relatives was a mainstay in Norse religion. Ancestors constituted one of the most ancient and widespread types of deity worshipped in the Nordic region. Although most scholarship focuses on the larger community's dedication to more fantastic gods and myths of the Vikings, it is understood that some sort of ancestor worship was probably an element of the private religious practices of the farmstead and village.[73] Often in addition to showing adoration to the standard Nordic gods, warriors would toast to “their kinsmen who lay in barrows”.[74]

Rather than viewing all these Gods as a holy figure or signaling one God to worship as their main father, the Norse Paganism religion offers the freedom to worship other worldly Gods. Together these families are all tied in as Gods within each other as it relates to humans connected through family. Rather than having these Gods illustrated as very holy figures, they are shown and described in a way that can blend within the human society. “Leading them is Oden Universal father, God of poetic inspiration, mystery of magic, and patron of warriors” (Page 1996, 7). The universal father Oden was married to Goddess Frigg “goddess who knows the fates of all men” (Page 1996, 7).[75] Amongst these two God and Goddess, there are multiple other Gods and Goddesses who are referred to as their children. For example, Thor, Tyr, and Bragi.

Priests

Most evidence suggests that cultic activity was largely the preserve of high-status males in Old Norse society.[76] However, there are exceptions. In Ibn Fadlan's account of his time among the Rus, he describes an elder woman known as the "Angel of Death" who oversaw a funerary ritual.[76]

It is often said that the Germanic kingship evolved out of a priestly office. This priestly role of the king was in line with the general role of goði, who was the head of a kindred group of families (for this social structure, see Norse clans), and who administered the sacrifices.

Iconography

Earlier examples of Mjöllnir pendants are made from iron, bronze, or amber.[29] Silver Mjöllnir pendants appear later in the period, becoming fashionable in the tenth century.[29] These were probably worn as amulets, good-luck charms, or sources of protection.[77] There is no evidence that they played a part in religious ceremonies.[78] However, around 10 percent of those discovered during excavation had been placed on top of cremation urns, suggesting that they had a place in certain funerary rituals.[78] When found in inhumation graves, Mjöllnir pendants are more likely to be found in women's graves then men's.[78]

The growing popularity of silver Mjöllnir pendants in the tenth century may have been a response to the growth in Christians wearing a cross as an amulet, something that also took place in that century.[78] The two religious symbols may have co-existed closely; one piece of archaeological evidence suggesting that this is the case is a soapstone mould for casting pendants discovered from Trengården in Denmark. This mould had space for a Mjöllnir and a crucifix pendant side by side, suggesting that the artisan who produced these pendants catered for both religious communities.[78]

Iconographic material suggesting other deities are less common that those connected to Thor.[78] Various images have been associated with Oðinn because they have one eye missing.[79] Examples include the Lindy figurine and the 'weapon-dancer' on the die from Torslanda.[79]

The term valknut is not Old Norse, but is a modern development.[80] These symbols may have a specific association with Oðinn, because they often accompany images of warriors on picture stones.[81]

Sacrifice

Sacrifice appears to have been one of the most important activities in Old Norse religion.[72] It is also one of the easiest practices to identify within the archaeological record.[72] Textual sources ranging from Tacitus to Adam of Bremen refer to the sacrifice of both humans and other animals as being part of the pre-Christian religious practices in Scandinavia.[82]

In most cases, it is not possible to archaeologically identify which deity a particular sacrifice may have been made to.[83] An exception is with Oðinn, whose sacrifices have been associated with certain markers.[83] It is unclear is such human sacrifices were conceived as being offerings to the gods, or whether they were instead sacrificed in imitation of Oðinn's self-sacrifice (as recounted in Hávamál).[65]

Examples in which a grave contains two bodies, one of whom has died from natural causes and the other from violence, it is possible that the latter was sacrificed to accompany the former in death, perhaps into an afterlife.[83] One example of this was found at Birka in Sweden, where a decapitated young man was placed atop an older male buried with weapons.[84] Another—from Gerdrup near to Roskilde, Denmark—featured a woman who was buried alongside a man whose neck had been broken.[84] There is also a textual reference to this practice, produced by Ibn Fadlan; he described a ship burial among the Rus that he had observed around the year 921. As part of the rite, a slave girl offered to be killed alongside her deceased master. She was given special clothing and drink for ten days, at which point the man's body had been placed within a wooden ship and provided him with weaponry, food and drink, and slaughtered animals. The slave girl had sexual intercourse with various men present—each of whom stated "Tell your master that I have done this purely out of love for you"—after which she was led into the ship and killed by being simultaneously stabbed and strangled by an elder woman known as the "Angel of Death".[85] Many of the material features in Ibn Fadlan's account match the evidence from the archaeological record, and it is possibly that those elements which are not visible in the archaeological evidence—such as the sexual elements of the ritual—would also have taken place more widely among the Norse.[86]

The Heimskringla tells of Swedish King Aun who sacrificed nine of his sons in an effort to prolong his life until his subjects stopped him from killing his last son Egil. According to Adam of Bremen, the Swedish kings sacrificed males every ninth year during the Yule sacrifices at the Temple at Uppsala. The Swedes had the right not only to elect kings but also to depose them, and both king Domalde and king Olof Trätälja are said to have been sacrificed after years of famine.

Odin, the chief god of the Norse, was associated with death by hanging, and a possible practice of Odinic sacrifice by strangling has some archeological support in the existence of bodies perfectly preserved by the acid of the Jutland (later taken over by the Daner people) peatbogs, into which they were cast after having been strangled. One of the most notable examples of this is the Bronze Age Tollund Man. However, we possess no written accounts that explicitly interpret the cause of these stranglings, which could have other explanations, such as being a form of capital punishment. Odin himself is hanged on the world tree Yggdrasil in the poem Havamal, and in Gautreks saga, king Vikar is hanged with the words, ‘Now I give you to Odin’.

I know that I hung on a windy treenine long nights, wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin, myself to myself, on that tree of which no man knows from where its roots run.

Havamal, st.138, Rúnatal or Óðins Rune Song.

Further evidence of human sacrifice can be preserved for thousands of years in the peat bogs, which were often used in religious ceremonies that included human sacrifice.[87] Another method of human sacrifice was burning to death. The ninth-century Berne Scholia describes how people were burnt in a wooden tub in honor of Taranis, the thunder god (Celtic religion). But the Eyrbyggja saga from the Icelandic Scandinavian influence tradition speak of human sacrifices in honor of the Scandinavian god Thor.[88]

Burial

There is only one explicit reference to Viking Age burial customs in Scandinavia within the Old Norse literary corpus.[76] This comes from Snorri Sturluson's Ynglinga Saga, where he states that Oðinn—whom he regards as a human king later mistaken for a deity—instituted laws that the dead would be burned on a pyre with their possessions, and burial mounds or memorial stones erected for the most notable men.[89] Snorri's account dates from a period long after these practices had died out, but his description has parallels with the archaeological evidence.[63]

Ship burial is attested in both Ibn Fadlan's written account and a number of archaeological sources.[76] Examples include the Oseberg ship burial near Tønsberg in Norway and an inhumation burial in a ship at Klinta on Öland.[76] A boat burial at Kaupand in Norway contained a man, woman, and baby lying adjacent to each other alongside the remains of a horse and dismembered dog. Within the stern of the boat was a second woman, decked out with weapons, jewellery, a bronze cauldron, and a metal staff; archaeologists have suggested that she may have been a sorceress.[76]

Influence

Traces and influences of Norse paganism can still be found in the culture and traditions of the modern Nordic countries; Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, the Åland Islands, and Greenland, as well as in other countries such as Germany, England, Canada and some parts of British North America and New Spain which were settled by migrants from Nordic nations.

Days of the week

| Old Norse | Faroese | Icelandic | Danish / Norwegian | Swedish | Finnish | Anglo-Saxon | German | Dutch | English | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mánadagr | Mánadagur | Mánudagur | Mandag - Måndag (Nn) | Måndag | Maanantai | Móndæg | Montag | Maandag | Monday | Moon's Day |

| Týsdagr | Týsdagur | Þriðjudagur | Tirsdag - Tysdag (Nn) | Tisdag | Tiistai | Tíwesdæg | Dienstag | Dinsdag | Tuesday | Tyr's Day |

| Óðinsdagr | Mikudagur/ Ónsdagur | Miðvikudagur | Onsdag | Onsdag | Keskiviikko | Wódnesdæg | Mittwoch/ Wunsdag | Woensdag | Wednesday | Odin's Day |

| Þórsdagr | Hósdagur/ Tórsdagur | Fimmtudagur | Torsdag | Torsdag | Torstai | Þunresdæg | Donnerstag | Donderdag | Thursday | Thor's Day |

| Frjádagr | Fríggjadagur | Föstudagur | Fredag | Fredag | Perjantai | Frigedæg | Freitag | Vrijdag | Friday | Frigg or Freyja's Day |

| Laugardagr | Leygardagur | Laugardagur | Lørdag-Laurdag (Nn) | Lördag | Lauantai | Sæternesdæg | Samstag / Sonnabend | Zaterdag | Saturday | Washing Day* |

| Sunnudagr | Sunnudagur | Sunnudagur | Søndag-Sundag (Nn) | Söndag | Sunnuntai | Sunnandæg | Sonntag | Zondag | Sunday | Sun's Day |

Note: 'Mikudagur' in Faroese, 'Miðvikudagur' in Icelandic, 'Keskiviikko' in Finnish and 'Mittwoch' in German means mid-week day. 'Saturday' in English, 'Samstag' in German and 'Zaterdag' in Dutch mean Saturn's Day, after the Roman god Saturn.

Festivals

Festivals were a public celebration of the divine, where the local community or the nation renewed its bonds through shared worship.[90] There were many elements to the Norse festivals, and it depended on which particular festival was being celebrated. Religious sacrifice was just one element of such festivals and holidays. The festivals were more so a place to celebrate one’s communal identity than to gather in a religious capacity.[90] This sense of the communal is underlined by the role of the local leader, whether king, chieftain or householder, in leading the rite.[90] These celebrations also served to reinforce the social bonds between the chieftain and his followers, joining everyone in a single community.

Pagan Survivals

Some cultural and religious beliefs of Post-Christian Scandinavia are believed to have originated from Pagan practices and beliefs and represent a "Cultural Paganism" that was not seen to be at odds with Christian belief. Folkloric beliefs in supernatural creatures such as elves and trolls, which are clearly taken from Norse mythology seem to suggest a survival of these beliefs through popular religion. Charms and other objects were widely popular among the common people during the Christian era as a defence against elves and other magical practices.[91] In the Eyrbyggja Saga a Christian woman requests to be buried in a Christian churchyard and after her death a number of companions partake on a two-day journey to bury her body, along the way they stop at a farmer's house but are rebuffed inhospitably. Later they hear strange noises and find that the women they are transporting is alive, stark naked and cooking them food in order to teach the farmers a lesson about hospitality.[92]

Scholarly study

Old Norse religion has attracted the interest of scholars since at least the mid-nineteenth century.[93] Many of the scholars operating in the nineteenth and twentieth-century were strongly influenced in their interpretations by modern romantic notions about nationhood, conquest, and religion.[93] Their understandings of cultural interaction was also coloured by nineteenth century European colonialism and imperialism.[93] Many regarded pre-Christian religion as singular and unchanging, directly equated religion with nation, and projected modern national borders onto the Viking Age past.[93]

Modern influences

Various modern celebrations in Nordic countries have traditions that arose from the festivals of the pre-Christian pagans.

The Christian celebration of Christmas, as practiced in Scandinavian nations and elsewhere, is still called Jul and makes use of pagan practices such as the Yule log, holly, mistletoe and the exchange of gifts. The celebration of Jul has gradually moved towards a secular event rather than a religious one. Depending on definition, between 45% and 80% of Scandinavians are non-religious.[94]

Midsummer, the celebration of the summer solstice, is an Old Norse practice still celebrated in Denmark and Germany (St John's Eve), Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia and Norway, and in towns across Canada, Greenland and British North America that were settled by Scandinavians.

Norse paganism was the inspiration behind the Neopagan religions of Asatru and Odinism, which originated in the 20th century.[95] They are both subsets of the larger Germanic neopaganism.

Notes

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ DuBois 1999, p. 8.

- 1 2 DuBois 1999, p. 5.

- ↑ DuBois 1999, p. 7.

- 1 2 DuBois 1999, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 81.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 10.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 3 4 Abram 2011, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abram 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 15.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 20.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 20, 21.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 24.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 25.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 25–26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abram 2011, p. 27.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 28.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 28–29.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abram 2011, p. 4.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 7.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abram 2011, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Abram 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 53.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 79.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 55.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, pp. 56–57.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 Abram 2011, p. 58.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Jolly 1996, p. 36; Pluskowski 2011, p. 774.

- ↑ Jesch 2011, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Gelling 1961, p. 13; Meaney 1970, p. 120; Jesch 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ Meaney 1970, p. 120.

- ↑ Jesch 2011, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Jesch 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ Jolly 1996, p. 36.

- ↑ Jolly 1996, pp. 41–43; Jesch 2004, p. 56.

- ↑ Pluskowski 2011, p. 774.

- ↑ Jesch 2004, p. 57.

- ↑ Jesch 2004, p. 61.

- ↑ Jesch 2004, pp. 57–59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Abram 2011, p. 61.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 62.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 84.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 64.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Dubois. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. p. 50.

- ↑ Sturluson, Snorri (1964). The Prose Edda Tales Mythology. California: University of California Press. p. 78.

- ↑ Dubois. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. p. 52.

- 1 2 Dubois. p. 54.

- ↑ Dunn, Charles (1990). "Poems of the Elder Edda". Volupsa. California: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 75.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 76.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 78.

- 1 2 ANDRÉN, ANDERS (2005-01-01). "Behind "Heathendom": Archaeological Studies of Old Norse Religion". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 27 (2): 105–138.

- ↑ Dubois. p. 85.

- ↑ Dubois. p. 87.

- ↑ Sephton, J. "The Saga of Erik the Red". 1880. Icelandic Saga Database. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Abram 2011, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abram 2011, p. 70.

- ↑ Gislason, Jonas (1990). Acceptance of Christianity in Iceland in the Year 1000:"Old Norse and Finnish Religions and pagan Place-Names. Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History. pp. 223–255.

- ↑ Sturluson, Snorri (1941). Froenda sinna, peira er heyfdir hofou verit. Heimskringla: Hakonar saga Goda. p. 168.

- ↑ Page, R.I. (1990). Norse Myths. British Museum publications. pp. 7 and 8. ISBN 0-292-75546-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abram 2011, p. 74.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 65–66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abram 2011, p. 66.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 67.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 77.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 70–71.

- 1 2 3 Abram 2011, p. 71.

- 1 2 Abram 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Abram 2011, p. 73.

- ↑ Ewing, Thor. Gods and worshippers. p. 18.

- ↑ Ewing, Thor. Gods and worshippers. p. 19.

- ↑ Abram 2011, pp. 74–75.

- 1 2 3 Nedkvitne, Arnved. p. 79. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Davidson, H. R. Ellis. 1988. Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe: Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- ↑ Chadwick, N. K. "Norse Ghosts (A Study in the Draugr and the Haugbúi)." Folklore 57, no. 2 (1946): Pg. 51

- 1 2 3 4 DuBois 1999, p. 11.

- ↑ http://www.pitzer.edu/academics/faculty/zuckerman/Ath-Chap-under-7000.pdf

- ↑ "Hvad er asatro idag? - Danish National museum (in Danish)". Retrieved 9 June 2016.

Sources

- Abram, Christopher (2011). Myths of the Pagan North: The Gods of the Norsemen. New York and London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1847252470.

- DuBois, Thomas A. (1999). Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812217148.

- Gelling, Margaret (1961). "Place-Names and Anglo-Saxon Paganism". University of Birmingham Historical Journal. 8: 7–25.

- Jesch, Judith (2004). "Scandinavians and 'Cultural Paganism' in Late Anglo-Saxon England". In Paul Cavill (ed.). The Christian Tradition in Anglo-Saxon England: Approaches to Current Scholarship and Teaching. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. pp. 55–68. ISBN 978-0859918411.

- ——— (2011). "The Norse Gods in England and the Isle of Man". In Daniel Anlezark (ed.). Myths, Legends, and Heroes: Essays on Old Norse and Old English Literature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 11–24. ISBN 978-0802099471.

- Jolly, Karen Louise (1996). Popular Religion in Late Saxon England: Elf Charms in Context. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807845653.

- Meaney, Audrey (1970). "Æthelweard, Ælfric, the Norse Gods and Northumbria". Journal of Religious History. 6 (2): 105–132. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1970.tb00557.x.

- Pluskowski, Aleks (2011). "The Archaeology of Paganism". In Helena Hamerow, David A. Hinton, and Sally Crawford (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 764–778. ISBN 978-0199212149.