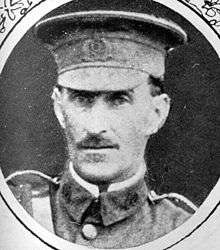

Norman Frederick Hastings

| Major Norman Frederick Hastings | |

|---|---|

Died of Wounds, Gallipoli, August 1915 | |

| Born |

14 July 1879 Auckland, New Zealand |

| Died |

9 August 1915 (aged 36) Gallipoli, Turkey |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service |

1899–1902 1905–08 1909–14 1914–15 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

34 Company Army Service Corps Rimington's Scouts and Guides Damant's Horse 6th (Manawatu) Mounted Rifles Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade New Zealand and Australian Division New Zealand Expeditionary Force |

| Commands held | 6th (Manawatu) Squadron, Wellington Mounted Rifles |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Distinguished Service Order Mentioned in Despatches Legion of Honour |

Major Norman Frederick Hastings, DSO (14 July 1879 – 9 August 1915) served as Officer Commanding New Zealand's 6th (Manawatu) Squadron, Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment. After serving with British military units during the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa, he worked as an engineering fitter with the New Zealand Railways Department workshops at Petone. He enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force at the outbreak of World War I, and served with distinction before dying of wounds after the attack on Chunuk Bair, Gallipoli, in August 1915. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (second only to the Victoria Cross for officers), was Mentioned in Despatches, and was one of only 14 members of the New Zealand Army to receive the French Legion of Honour decoration during the war. The memorial flagstaff at Petone railway station appears to have been erected in his honour, and was the site of New Zealand's first public Anzac Day ceremony on 25 April 1916.

Early life

Norman Hastings was born in Auckland on 14 July 1879, the son of Frederick and Fanny Hastings.[1][2][nb 1] He was raised in Brooklyn, Wellington, and his military service began in the 1890s when he served as a private for two and a half years with the Wellington City Rifles.[1]

Boer War

Hastings took part in the Second Anglo-Boer War in South Africa, serving with British troops despite his New Zealand roots. He enlisted into 34 Company Army Service Corps on 10 August 1900. Holding the rank of conductor, he remained with the company until 19 February 1901 when he was transferred at his own request to a mounted unit, Rimington's Scouts and Guides.[1] Shortly before Hastings had arrived, Major Frederick Damant had taken over command of the unit and it later became known as Damant's Horse. Working with Major General (later General) Bruce Hamilton's 21st Brigade in Cape Colony to drive out Boer forces led by Christiaan de Wet,[3] Hastings gained the rank of sergeant and was wounded in action twice while serving with the unit. For a six-month period, he was detached from Damant's Horse, serving in Hamilton's field intelligence unit, during which time he commanded a group of native scouts.[1]

Between the wars

After the conclusion of the Boer War, Hastings returned to New Zealand. In 1905, he recommenced his military service by enlisting in the Karori Defence Rifle Club. He served with the Club until 1908 when he married Hilda May Barr of Masterton.[4] On 1 June 1909, Hastings was appointed Commander of the Dominion Scouts, E Squadron 2nd Mounted Rifles Regiment, a volunteer unit in Wellington, holding the rank of acting lieutenant. He later passed a promotion examination and was formally commissioned as a lieutenant with effect 1 December 1909. In 1911 he tried unsuccessfully to gain an appointment to the permanent staff of the New Zealand Army as an adjutant or instructor. During a period of significant reorganisation of the New Zealand Military Forces, Hastings was instead posted to A Squadron, 6th (Manawatu) Mounted Rifles, which was established as a new unit on 17 March 1911. Serving in a part-time capacity, he then successfully passed the examination for promotion to captain and was granted that rank with effect 16 October 1912.[1][5] During this period Hastings settled in Petone where he commenced working for the New Zealand Railways Department as an engineering fitter and foreman, and with his wife raised two children: Francis Norman and Marjory.[2][6][7]

World War I

After the New Zealand Government declared war on Germany it decided to establish the New Zealand Expeditionary Force for overseas service. As a part of this force, the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment was formed and began concentrating at Awapuni racecourse in Palmerston North from 12 August 1914. Hastings joined the unit in the Manawatu and was attested on 13 August 1914, enlisting into the 6th Squadron as second-in-command under Major Charles Dick.[8] The unit formed part of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade commanded by Brigadier-General Andrew Hamilton Russell, and departed New Zealand on board the troopship Tahiti on 15 October 1914. This vessel was one of twelve troop ships that carried the main body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in a convoy escorted by Allied warships. After departing New Zealand, the convoy stopped at Hobart, Albany and Colombo before arriving at the Suez Canal on 1 December 1914. In Egypt, the New Zealand Expeditionary Force established a training camp at Zeitoun, with the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade remaining behind as the New Zealand Infantry Brigade participated in British operations against the Ottomans in the Suez Canal area in February 1915, before taking part in the invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula in late April 1915.[9]

Service at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli landings were strongly resisted by Ottoman forces, and reinforcements were required. Thus, in early May the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment was advised to prepare for embarkation for Gallipoli to join the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade. On 12 May 1915, Hastings arrived at Anzac Cove and the following day his regiment occupied Walker's Ridge. From then on, Hastings displayed strong leadership as the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment anchored the brigade's position in defence of the ANZAC perimeter. On 19 May, the Ottomans launched a major offensive that saw 42,000 Ottomans attack the 17,000 ANZACs holding the beachhead. In response, the 6th Squadron prepared to take part in a counterattack, but this was subsequently called off.[10] After the Canterbury Mounted Rifle Regiment attacked and seized a new outpost (initially called No. 3 Outpost) on 28 May, the 6th Squadron relieved them and began digging defences.[11] The outpost was then handed over to another squadron who came under a sustained attack throughout 29 May and were forced to withdraw on 30 May, while the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment continued the battle without rest for 28 hours.[12] The unit history noted that during this time, Hastings "... performed most useful and hazardous work ..." closely reconnoitring the enemy's position and furnishing "... a most accurate report on the situation, which proved of great value".[13] As the outpost was relinquished around midnight on 30 May the Ottomans aggressively followed up the withdrawing troops until Hastings led an advance along the ridge that enabled heavy fire to be brought down on the enemy's position. Hastings' men then launched a "most effective" attack with bayonets that "... broke the Turkish onrush".[13] The ANZACs subsequently established a new outpost closer to the existing line, No. 3 Outpost, with the position now held by the enemy referred to as the Old No. 3 Outpost.[14]

August Offensive

In early August 1915, Hastings was heavily involved in the Allied offensive that attempted to break the deadlock of the Gallipoli campaign through the simultaneous push for the heights above Anzac and lodgement of a new British force at Suvla Bay. After dark on 6 August the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade commenced its task of clearing the Ottomans from the lower slopes of the Sari Bair range beginning with the Old No. 3 Outpost. During this attack Hastings led two platoons of Maori Pioneers in destroying barbed-wire entanglements in the Sazli Beit Dere before the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment stormed Destroyer Hill and Table Top.[15] Hastings' party assisted the Auckland Mounted Rifles Regiment by attacking trenches in the Old No. 3 Outpost and took some prisoners on the northern end of the position.[16] Hastings subsequently assumed command of the 6th Squadron after the Officer Commanding, Major Charles Dick, was wounded in the assault on Destroyer Hill, which opened the way to Table Top and allowed the New Zealand Infantry Brigade to seize Rhododendron Ridge in preparation for the attack on Chunuk Bair. The Wellington Infantry Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel William George Malone managed to secure the summit of Chunuk Bair in the early hours of 8 August, and took heavy casualties throughout the day until reinforced by the Otago Infantry Battalion and the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment in the evening. Promoted in the field to major, Hastings commanded the 6th Squadron on Chunuk Bair on 8 and 9 August as the New Zealanders attempted to hold the position against fierce Ottoman counterattacks. Casualties were heavy and on the morning of 9 August Hastings was wounded when a bomb exploded, shattering his leg. His evacuation was significantly delayed by the terrain and congested approaches to the heights, and the dangers encountered by his stretcher bearers, but he was successfully admitted to the casualty clearing station down on the beach.[17]

Death

It is unclear what happened to the wounded Hastings, and there appears to have been confusion at the time as he was subsequently reported as "missing, presumed dead".[1] Hastings had been evacuated to North Beach into the care of the 16th (British) Casualty Clearing Station, near Embarkation Pier, which had been constructed for the purpose of evacuating wounded during the August Offensive but had been abandoned when it came under heavy rifle and shell fire after just two days.[18] As he could not be evacuated to a hospital ship it is likely that Hastings died while at the casualty clearing station and was buried in haste due to the massive number of Allied casualties. Despite his missing-in-action status Hastings was gazetted as a temporary major on 16 December 1915, and subsequently confirmed as a substantive major on 11 February 1916.[1] In the meantime, following the evacuation of the Allied force from Gallipoli, a court of inquiry was initiated at Zeitoun on 17 January 1916. The inquiry was concluded at Serapeum on 3 March 1916, where the Commanding Officer of the Wellington Mounted Rifle Regiment determined that Hastings had probably died of wounds received in action on 9 August 1915.[1] This deduction was later confirmed when Hastings' assumed burial place in the Embarkation Pier Cemetery was marked with a special memorial by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission after the war.[19]

Awards and decorations

In recognition of Hastings' outstanding bravery and leadership the award of the Distinguished Service Order was gazetted on 14 January 1916 for distinguished service in the field on Gallipoli.[20][21][22] He was also Mentioned in Despatches on 28 January 1916 in recognition of his excellent service[22][23] and appointed a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour by the President of France.[24][25] This French award is uncommon to New Zealanders: fewer than 100 awards have been made, and Hastings was one of only 14 members of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force to be decorated with the Legion of Honour during the war.[25][26]

Ribbons

-

Distinguished Service Order (Great Britain)[20][21][22]

Distinguished Service Order (Great Britain)[20][21][22] -

Queen's South Africa Medal (three clasps: Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal) (Great Britain)[27]

Queen's South Africa Medal (three clasps: Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal) (Great Britain)[27] -

King's South Africa Medal (two clasps: South Africa 1901, South Africa 1902) (Great Britain)[27]

King's South Africa Medal (two clasps: South Africa 1901, South Africa 1902) (Great Britain)[27] -

1914–15 Star (Great Britain)[21]

1914–15 Star (Great Britain)[21] -

British War Medal 1914–19 (Great Britain)[21]

British War Medal 1914–19 (Great Britain)[21] -

Victory Medal with Mention in Despatches (Great Britain)[22][23]

Victory Medal with Mention in Despatches (Great Britain)[22][23] -

Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (France)[24][25]

Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (France)[24][25]

Commemoration

Hastings was commemorated on the stone laid below the Petone Anzac Memorial Flagstaff by members of the New Zealand Railways Department. The memorial was the focal point of the first public Anzac Day remembrance ceremony in New Zealand on 25 April 1916, which was attended by the Prime Minister of New Zealand, William Massey, and other members of Parliament.[28] Even though Hastings' death had not been confirmed at the time, it is believed that the desire to commemorate him was a key motivation in the erection of the memorial.[7] Hastings' name is also included on the Memorial Tablet engraved with the names of 446 New Zealand Railways Department workers who were killed during World War I, which was unveiled in the Railways Head Office at Wellington on 28 April 1922 by the Prime Minister.[29][30]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Hastings' date of birth is widely disputed and listed differently in three separate locations within his service file. The widely published 12 July 1885 date would have made Hastings only 14 years old on enlistment in the British Army so is most likely incorrect. Hastings also gives his date of birth as 12 July 1880 on his enlistment into the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in August 1914, but his date of birth is listed three times in his Territorial Force service file as 14 July 1879 and that is the one listed here.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "New Zealand Defence Force Personnel File Norman Frederick HASTINGS, New Zealand Archives Reference: AABK 18805 W5515 0006343". Archives New Zealand. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- 1 2 "New Zealand Defence Force Personnel File Norman Frederick HASTINGS, New Zealand Archives Reference: AABK 18805 W5539 0052011". Archives New Zealand. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ↑ Biggins, David (13 September 2010). "Damant's Horse". AngloBoerWar.com. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ Curran, Bryan (23 May 2001). "NEW-ZEALAND-L Archives". Rootsweb, Ancestry.com. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ Ministry for Culture and Heritage (16 March 2011). "6th (Manawatu) Mounted Rifles". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ Armoury Information Centre (2011). "Auckland War Memorial Museum Cenotaph, Norman Frederick Hastings". Auckland War Memorial Museum. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- 1 2 Astwood, Karen (10 February 2011). "ANZAC Memorial Flagpole". New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ↑ Wilkie, Alexander, Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, Wellington, Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd, 1924, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Taylor, Richard, Tribe of the War God: Ngati Tumatauenga, Napier, NZ: Heritage, 1996, p.49.

- ↑ Wilkie, Alexander, Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, Wellington, Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd, 1924, pp.14–26.

- ↑ Pugsley, Christopher, Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story (2nd ed.), Auckland: Reed, 1998, p.230.

- ↑ Kinloch, Terry, Echoes of Gallipoli: In the words of New Zealand's Mounted Riflemen, Auckland: Exisle, 2005, p.149.

- 1 2 Wilkie, Alexander, Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, Wellington, Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd, 1924, pp.33–34.

- ↑ Stowers, Richard, Bloody Gallipoli: The New Zealanders' Story, Auckland: David Bateman, 2005, p.104.

- ↑ Cameron, David W., Australian Army Campaigns Series – 10: The August Offensive at ANZAC, 1915, Canberra, ACT Australia: Australian Army History Unit, Commonwealth of Australia, 2001, p.42.

- ↑ Wilkie, Alexander, Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, Wellington, Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd, 1924, p.47.

- ↑ Wilkie, Alexander, Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment, Wellington, Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd, 1924, p.59.

- ↑ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery Details Embarkation Pier Cemetery". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ "Casualty Details: Hastings, Norman Frederick". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- 1 2 "No. 29438". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 January 1916. p. 576.

- 1 2 3 4 Haigh, Bryant & Polaschek, Allan, New Zealand and the Distinguished Service Order, Christchurch: John. D. Wills, 1993, p.118.

- 1 2 3 4 McDonald, Wayne, Honours and Awards to the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in the Great War 1914–1918, Napier: H. McDonald, 2001, p.137.

- 1 2 "No. 29455". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 January 1916. p. 1210.

- 1 2 "No. 29486". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 February 1916. p. 2066.

- 1 2 3 Brewer, Mark, 'New Zealand and the Legion d'honneur: The Great War, Part One', The Volunteers: The Journal of the New Zealand Military Historical Society, 37(2), November 2011, p.114.

- ↑ Brewer, Mark, 'New Zealand and the Legion d'honneur: The Great War, Part Three', The Volunteers: The Journal of the New Zealand Military Historical Society, 38(1), July 2012, pp.20–23.

- 1 2 Dolan, Bryn; Meyers, John (8 May 2012). "Lost Leaders of Anzacs: Anzac Officers Died at Gallipoli". B. Dolan & J. Meyers. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ↑ Edwards, Simon (11 January 2011). "Petone flagpole considered for highest heritage protection". The Hutt News. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ Davidson, Gerald (27 April 2008). "The ANZAC Memorial Flagstaff, Petone Railway Station". Hutt Valley Signals. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ Mellor, Mike (18 October 2011). "Wellington Railway Station war memorial". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

External links

- "Auckland War Memorial Museum Cenotaph, Norman Frederick Hastings".

- "Wellington Railway Station war memorial".

- "The Official War History of the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment 1914–1919, by Major A.H. Wilkie NZMR".

- "New Zealand History online, Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment".

- "NZMR Association, The Wellington Mounted Rifles".

- "Desert Column, New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade".

- "Desert Column, Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment".