Norfolk

| Norfolk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | |||||

| |||||

Norfolk in England | |||||

| Sovereign state |

| ||||

| Country |

| ||||

| Region | East of England | ||||

| Established | Anglo-Saxon period[1] | ||||

| Ceremonial county | |||||

| Lord Lieutenant | Richard Jewson | ||||

| High Sheriff | James Bagge[2] (2017-18) | ||||

| Area | 5,372 km2 (2,074 sq mi) | ||||

| • Ranked | 5th of 48 | ||||

| Population (mid-2016 est.) | 892,900 | ||||

| • Ranked | 25th of 48 | ||||

| Density | 165/km2 (430/sq mi) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 96.5% white[3] | ||||

| Non-metropolitan county | |||||

| County council | Norfolk County Council | ||||

| Executive | Conservative | ||||

| Admin HQ | Norwich | ||||

| Area | 5,372 km2 (2,074 sq mi) | ||||

| • Ranked | of 27 | ||||

| Population | 892,900 | ||||

| • Ranked | 7th of 27 | ||||

| Density | 165/km2 (430/sq mi) | ||||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-NFK | ||||

| ONS code | 33 | ||||

| NUTS | UKH13 | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

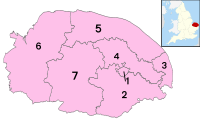

Districts of Norfolk | |||||

| Districts | |||||

| Members of Parliament | |||||

| Police | Norfolk Constabulary | ||||

| Time zone | Greenwich Mean Time (UTC) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time (UTC+1) | ||||

Norfolk (/ˈnɔːrfək/) is a county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the west and north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and southwest, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North Sea and, to the north-west, The Wash. The county town is Norwich. With an area of 2,074 square miles (5,370 km2) and a population of 859,400, Norfolk is a largely rural county with a population density of 401 per square mile (155 per km²). Of the county's population, 40% live in four major built up areas: Norwich (213,000), Great Yarmouth (63,000), King's Lynn (46,000) and Thetford (25,000).[4]

The Broads is a network of rivers and lakes in the east of the county, extending south into Suffolk. The area is not a National Park[5] although it is marketed as such. It has similar status to a national park, and is protected by the Broads Authority.[6]

History

Norfolk was settled in pre-Roman times, with camps along the higher land in the west, where flints could be quarried.[7] A Brythonic tribe, the Iceni, inhabited the county from the 1st century BC to the end of the 1st century AD. The Iceni revolted against the Roman invasion in AD 47, and again in 60 led by Boudica. The crushing of the second rebellion opened the county to the Romans. During the Roman era roads and ports were constructed throughout the county and farming was widespread.

Situated on the east coast, Norfolk was vulnerable to invasions from Scandinavia and Northern Europe, and forts were built to defend against the Angles and Saxons. By the 5th century the Angles, after whom East Anglia and England itself are named, had established control of the region and later became the "north folk" and the "south folk", hence, "Norfolk" and "Suffolk". Norfolk, Suffolk and several adjacent areas became the kingdom of East Anglia (one of the heptarchy), which later merged with Mercia and then with Wessex. The influence of the Early English settlers can be seen in the many place names ending in "-ton" and "-ham". Endings such as "-by" and "-thorpe" are also common, indicating Danish place names: in the 9th century the region again came under attack, this time from Danes who killed the king, Edmund the Martyr. In the centuries before the Norman Conquest the wetlands of the east of the county began to be converted to farmland, and settlements grew in these areas. Migration into East Anglia must have been high: by the time of the Domesday Book survey it was one of the most densely populated parts of the British Isles. During the high and late Middle Ages the county developed arable agriculture and woollen industries. Norfolk's prosperity at that time is evident from the county's large number of medieval churches: out of an original total of over one thousand, 659 have survived, more than in the whole of the rest of Great Britain.[8] The economy was in decline by the time of the Black Death, which dramatically reduced the population in 1349. By the 16th century Norwich had grown to become the second largest city in England; but over one-third of its population died in the plague epidemic of 1579,[9] and in 1665 the Great Plague again killed around one-third of the population.[10] During the English Civil War Norfolk was largely Parliamentarian. The economy and agriculture of the region declined somewhat. During the Industrial Revolution Norfolk developed little industry except in Norwich which was a late addition to the railway network.

In the 20th century the county developed a role in aviation. The first development in airfields came with the First World War; there was then a massive expansion during the Second World War with the growth of the Royal Air Force and the influx of the American USAAF 8th Air Force which operated from many Norfolk airfields. During the Second World War agriculture rapidly intensified, and it has remained very intensive since, with the establishment of large fields for growing cereals and oilseed rape.

Management of the shoreline

Norfolk's low-lying land and easily eroded cliffs, many of which are chalk and clay, make it vulnerable to the sea; the most recent major event was the North Sea flood of 1953. The low-lying section of coast between Kelling and Lowestoft Ness in Suffolk is currently managed by the Environment Agency to protect the Broads from sea flooding. Management policy for the North Norfolk coastline is described in the North Norfolk Shoreline Management Plan, which was published in 2006 but has yet to be accepted by the local authorities.[11] The Shoreline Management Plan states that the stretch of coast will be protected for at least another 50 years, but that in the face of sea level rise and post-glacial lowering of land levels in the South East, there is an urgent need for further research to inform future management decisions, including the possibility that the sea defences may have to be realigned to a more sustainable position. Natural England have contributed some research into the impacts on the environment of various realignment options. The draft report of their research was leaked to the press, who created great anxiety by reporting that Natural England plan to abandon a large section of the Norfolk Broads, villages and farmland to the sea to save the rest of the Norfolk coastline from the impact of climate change.[12]

Economy and industry

In 1998 Norfolk had a Gross Domestic Product of £9,319 million, which represents 1.5% of England's economy and 1.25% of the United Kingdom's economy. The GDP per head was £11,825, compared to £13,635 for East Anglia, £12,845 for England and £12,438 for the United Kingdom. In 1999–2000 the county had an unemployment rate of 5.6%, compared to 5.8% for England and 6.0% for the UK.[13]

Important business sectors include tourism, energy (oil, gas and renewables), advanced engineering and manufacturing, and food and farming.

Much of Norfolk's fairly flat and fertile land has been drained for use as arable land. The principal arable crops are sugar beet, wheat, barley (for brewing) and oil seed rape. The county also boasts a saffron grower.[14] Over 20% of employment in the county is in the agricultural and food industries.[15]

Well-known companies in Norfolk are Aviva (formerly Norwich Union), Colman's (part of Unilever), Lotus Cars and Bernard Matthews Farms. The Construction Industry Training Board is based on the former airfield of RAF Bircham Newton. The BBC East region is centred on Norwich, although it covers an area as far west as Milton Keynes; the BBC does however provide BBC Radio Norfolk solely for the county.

A Local Enterprise Partnership has recently been established by business leaders to help grow jobs across Norfolk and Suffolk. They have secured an enterprise zone to help grow businesses in the energy sector, and established the two counties as a centre for growing services and products for the green economy.

To help local industry in Norwich, the local council offered a wireless internet service but this has now been withdrawn as funding has ceased.[16]

Gallery

- River Wensum, Norwich

Norwich Cathedral: spire and south transept

Norwich Cathedral: spire and south transept

Education

Primary and secondary education

Norfolk has a completely comprehensive state education system, with secondary school age from 11 to 16 or in some schools with sixth forms, 18 years old. In many of the rural areas, there is no nearby sixth form and so sixth form colleges are found in larger towns. There are twelve independent, or private schools, including Gresham's School in Holt in the north of the county, Thetford Grammar School in Thetford which is Britain's fifth oldest extant school, Langley School in Loddon, and several in the city of Norwich, including Norwich School and Norwich High School for Girls. The King's Lynn district has the largest school population. Norfolk is also home to Wymondham College, the UK's largest remaining state boarding school.

Tertiary education

The University of East Anglia is located on the outskirts of Norwich and Norwich University of the Arts is based in seven buildings in and around St George's Street in the city centre, next to the River Wensum.

The City College Norwich and the College of West Anglia are colleges covering Norwich and King's Lynn as well as Norfolk as a whole. Easton & Otley College, 7 miles (11 km) west of Norwich, provides agriculture-based courses for the county, parts of Suffolk and nationally.

University Campus Suffolk also run higher education courses in Norfolk, from multiple locations including Great Yarmouth College.[16]

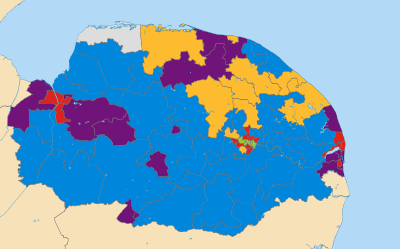

Politics

Local

Norfolk is under the control of Norfolk County Council and is also divided into seven local government districts: Breckland District, Broadland District, Great Yarmouth Borough, King's Lynn and West Norfolk Borough, North Norfolk District, Norwich City and South Norfolk District. As of 2014 the Conservatives controlled five of the seven districts, while Norwich is controlled by Labour and Great Yarmouth is under no overall control.

The county is traditionally a stronghold for the Conservatives, who have always won at least 50% of Norfolk's parliamentary constituencies since 1979. The countryside is mostly solid Conservative territory, with a few areas being strong for the Liberal Democrats. From 1995 to 2007, South Norfolk was run by the Liberal Democrats, but the district switched back to the Conservatives in a landslide in 2007.

Norfolk's urban areas are more mixed, although Norwich and central parts of Great Yarmouth and King's Lynn are strong for the Labour Party. This said, Labour's dominance in Norwich has recently been stemmed by the Green Party, who are now the official opposition on Norwich City Council and also hold several divisions within the city on Norfolk County Council.

Norfolk County Council had been under Conservative control since 1997, but they lost overall control at the 2013 election, when the Conservatives lost 20 seats and UKIP gained 14. As at 2013 there are 40 Conservative councillors, 15 UKIP, 14 Labour, 10 Liberal Democrats, 4 Green Party and one independent.[17] Although the Conservatives had been expected to form a minority administration or to seek a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, both scenarios failed to materialise. Eventually, a rainbow alliance between Labour, the Liberal Democrats, Greens and UKIP was formed, with the cabinet composed solely of Labour and Liberal Democrats.

Norwich Unitary Authority dispute

In October 2006, the Department for Communities and Local Government produced a Local Government White Paper inviting councils to submit proposals for unitary restructuring. In January 2007 Norwich submitted its proposal, which was rejected in December 2007 as it did not meet the criteria for acceptance. In February 2008, the Boundary Committee for England (from 1 April 2010 incorporated in the Local Government Boundary Commission for England) was asked to consider alternative proposals for the whole or part of Norfolk, including whether Norwich should become a unitary authority, separate from Norfolk County Council. In December 2009, the Boundary Committee recommended a single unitary authority covering all of Norfolk, including Norwich.[18][19][20][21]

However, on 10 February 2010, it was announced that, contrary to the December 2009 recommendation of the Boundary Committee, Norwich would be given separate unitary status.[22] The proposed change was strongly resisted, principally by Norfolk County Council and the Conservative opposition in Parliament.[23] Reacting to the announcement, Norfolk County Council issued a statement that it would seek leave to challenge the decision in the courts.[24] A letter was leaked to the local media in which the Permanent Secretary for the Department for Communities and Local Government noted that the decision did not meet all the criteria and that the risk of it "being successfully challenged in judicial review proceedings is very high".[25] The Shadow Local Government and Planning Minister, Bob Neill, stated that should the Conservative Party win the 2010 general election, they would reverse the decision.[26]

Following the 2010 general election, Eric Pickles was appointed Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government on 12 May 2010 in a Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government. According to press reports, he instructed his department to take urgent steps to reverse the decision and maintain the status quo in line with the Conservative Party manifesto.[27][28] However, the unitary plans were supported by the Liberal Democrat group on the city council, and by Simon Wright, LibDem MP for Norwich South, who intended to lobby the party leadership to allow the changes to go ahead.[29]

The Local Government Act 2010 to reverse the unitary decision for Norwich (and Exeter and Suffolk) received Royal Assent on 16 December 2010. The disputed award of unitary status had meanwhile been referred to the High Court, and on 21 June 2010 the court (Mr. Justice Ouseley, judge) ruled it unlawful, and revoked it. The city has therefore failed to attain permanent unitary status, and the previous two-tier arrangement of County and District Councils (with Norwich City Council counted among the latter) remains the status quo.[30]

Westminster

Following the May 2015 General Election, Norfolk is represented in the House of Commons by seven Conservative members of parliament, one Labour Member of Parliament and one Liberal Democrat.

| Parliamentary 6 May 2010 | County Council 2 May 2013 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | Votes % | Seats | Seats % | Party | Votes | Votes % | Seats | Seats % | ||

| Conservative | 188,944 | 43.1% | 7 | 77.8% | Conservative | 70,249 | 32.6% | 40 | 47.6% | ||

| Liberal Democrat | 121,710 | 27.8% | 2 | 22.2% | UKIP | 50,568 | 23.5% | 14 | 17.9% | ||

| Labour | 83,088 | 19.0% | 0 | 0% | Labour | 49,028 | 22.8% | 13 | 16.7% | ||

| UKIP | 20,182 | 4.6% | 0 | 0% | Liberal Democrat | 23,645 | 11.0% | 10 | 11.9% | ||

| Green | 14,119 | 4.8% | 4 | 6.6% | |||||||

| Others [1] | 24,302 | 5.5% | 0 | 0% | Others [2] | 58,424 | 27.0% | 15 | 19.1% | ||

| Totals | 438,226 | 9 | 215,465 | 84 | |||||||

| Turnout | 66.8% | 32.1% | |||||||||

[1] Green, LCA, Independents, Others

[2] UKIP, LCA, Independents, Others

Settlements

Norfolk's county town and only city is Norwich, one of the largest settlements in England during the Norman era. Norwich is home to the University of East Anglia, and is the county's main business and culture centre. Other principal towns include the port-town of King's Lynn and the seaside resort and Broads gateway town of Great Yarmouth.

Based on the 2011 Census[4] the county's largest centres of population are: Norwich (213,166), Great Yarmouth (63,434), King's Lynn (46,093), Thetford (24,883), Dereham (20,651), Wymondham (13,587), North Walsham (12,463), Attleborough (10,549), Downham Market (9,994), Diss (9,829), Fakenham (8,285), Cromer (7,749), Sheringham (7,367) and Swaffham (7,258). There are also several smaller market towns: Aylsham (6,016), Harleston (4,458) and Holt (3,810).

Much of the county remains rural in nature and Norfolk is believed to have around 200 lost settlements which have been largely or totally depopulated since the medieval period. These include places lost to coastal erosion, agricultural enclosure, depopulation and the establishment of the Stanford Training Area in 1940.

Transport

Norfolk is one of the few counties in England that does not have a motorway. The A11 connects Norfolk to Cambridge and London via the M11. From the west there only two routes from Norfolk that have a direct link with the A1, the A47 which runs into the East Midlands and to Birmingham via Peterborough and the A17 which runs into the East Midlands via Lincolnshire. These two routes meet at King's Lynn which is also the starting place for the A10 which provides West Norfolk with a direct link to London via Ely, Cambridge and Hertford . The Great Eastern Main Line is a major railway from London Liverpool Street Station to Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk. Norwich International Airport offers flights within Europe including a link to Amsterdam which offers onward flights throughout the world.

Dialect, accent and nickname

The Norfolk dialect is also known as "Broad Norfolk", although over the modern age much of the vocabulary and many of the phrases have died out due to a number of factors, such as radio, TV and people from other parts of the country coming to Norfolk. As a result, the speech of Norfolk is more of an accent than a dialect, though one part retained from the Norfolk dialect is the distinctive grammar of the region.

People from Norfolk are sometimes known as Norfolk Dumplings,[31] an allusion to the flour dumplings that were traditionally a significant part of the local diet.[32]

More cutting, perhaps, was the pejorative medical slang term "Normal for Norfolk",[33] alluding to the county's perceived status as a quirky rustic backwater.[34]

Tourism

Norfolk is a popular tourist destination and has several major holiday attractions. There are many seaside resorts, including some of the finest British beaches, such as those at Great Yarmouth, Cromer and Holkham. Norfolk contains the Broads and other areas of outstanding natural beauty and many areas of the coast are wild bird sanctuaries and reserves with some areas designated as National Parks such as the Norfolk Coast AONB.

Elm Hill in the historic city of Norwich

The Norfolk Coast in the little village of Mundesley near Cromer

The bridge at Wroxham

The beach at Holkham National Nature Reserve

The Queen's residence at Sandringham House in Sandringham, Norfolk provides an all year round tourist attraction whilst the coast and some rural areas are popular locations for people from the conurbations to purchase weekend holiday homes. Arthur Conan Doyle first conceived the idea for The Hound of the Baskervilles whilst holidaying in Cromer with Bertram Fletcher Robinson after hearing local folklore tales regarding the mysterious hound known as Black Shuck.[35][36]

Amusement parks and zoos

Norfolk has several amusement parks and zoos.

- Thrigby Hall near Great Yarmouth was built in 1736 by Joshua Smith Esquire and features a zoo which houses a large tiger enclosure, primate enclosures and the swamp house which has many crocodiles and alligators.

- Holkham Hall is an 18th-century stately home and visitor attraction, constructed in the Palladian style and at the centre of a 3,000 acre deer park on the North Norfolk coast with a woodland play area, walled garden and farming exhibition.

- Pettitts Animal Adventure Park at Reedham is a park with a mix of animals, rides and live entertainment shows.

- Great Yarmouth Pleasure Beach is a free-entry theme park, hosting over 20 large rides as well as a crazy golf course, water attractions, children's rides and "white knuckle" rides.

- BeWILDerwood is an award-winning adventure park situated in the Norfolk Broads and is the setting for the book A Boggle at BeWILDerwood by local children's author Tom Blofeld.

- Britannia Pier on the coast of Great Yarmouth has rides which include a ghost train. Also on the pier is the famous Britannia Pier Theatre.

- Banham Zoo is set amongst 35 acres (14 ha) of parkland and gardens with innovative enclosures providing sanctuary for almost 1,000 animals including big cats, birds of prey, siamangs and shire horses. Its annual visitor attendance is in excess of 200,000 people. It was awarded the prize of "Best Large Attraction" by Tourism in Norfolk in 2010.

- Amazona Zoo is situated on 10 acres (4.0 ha) of derelict woodland and abandoned brick kilns on the outskirts of Cromer and is home to a range of tropical South American animals including jaguars, otters, monkeys and flamingos.

- Amazonia is a tropical jungle environment in Great Yarmouth housing over 70 different species of reptiles including lizards, crocodiles, snakes, tortoises and terrapins.

- Pensthorpe Nature Reserve, near the town of Fakenham in north Norfolk, is a nature reserve with many captive birds and animals. Such species include native birds such as lapwing and Eurasian crane, to much more exotic examples like Marabou stork, Greater flamingo, and Manchurian crane. The site played host to BBC's 'Springwatch' from 2008 until 2010. A number of man-made lakes are home to a range of wild birds, and provide stop-off points for many wintering ducks and geese.

- Extreeme Adventure is a high ropes course built in some of the tallest trees in eastern England. In the 'New Wood' part of Weasenham Woods, Norfolk.

- The Sea Life Centre in Great Yarmouth is One of the biggest sea life centres in the country. The Great Yarmouth centre is home to a tropical shark display, one resident of which is Britain's biggest shark 'Nobby' the Nurse Shark. The same display, with its walk-through underwater tunnel, also features the wreckage of a World War II aircraft. The centre also includes over 50 native species including shrimps, starfish, sharks, stingrays and conger eels.

- The Sea Life Sanctuary in Hunstanton is Norfolk's leading marine rescue centre and works both as a visitor attraction as well as a location for rescuing and rehabilitating sick and injured sea creatures found in the nearby Wash and North Sea. The attractions main features are similar to that of the Sea Life Centre in Great Yarmouth, albeit on a slightly smaller scale.

Theatres

The Pavilion Theatre (Cromer) is a 510-seater venue on the end of Cromer Pier, best known for hosting the 'end-of-the-pier' show, the Seaside Special. The theatre also presents comedy, music, dance, opera, musicals and community shows.

The Britannia Pier Theatre (Great Yarmouth) mainly hosts popular comedy acts such as the Chuckle Brothers and Jim Davidson. The theatre has 1,200 seats and is one of the largest in Norfolk.

The Theatre Royal (Norwich) has been on its present site for nearly 250 years, the Act of Parliament in the tenth year of the reign of George II having been rescinded in 1761. The 1,300-seat theatre, the largest in the city, hosts a mix of national touring productions including musicals, dance, drama, family shows, stand-up comedians, opera and pop.

The Norwich Playhouse (Norwich) hosts theatre, comedy, music and other performing arts. It has a seating capacity of 300.

The Maddermarket Theatre (Norwich) opened in 1921 and was the first permanent recreation of an Elizabethan theatre. The founder was Nugent Monck who had worked with William Poel. The theatre has a seating capacity of 312.[37]

The Norwich Puppet Theatre (Norwich) was founded in 1979 by Ray and Joan DaSilva as a permanent base for their touring company and was first opened as a public venue in 1980, following the conversion of the medieval church of St. James in the heart of Norwich. Under subsequent artistic directors – Barry Smith and Luis Z. Boy – the theatre established its current pattern of operation. It is a nationally unique venue dedicated to puppetry, and currently houses a 185-seat raked auditorium, 50 seat Octagon Studio, workshops, an exhibition gallery, shop and licensed bar. It is the only theatre in the Eastern region with a year-round programme of family-centred entertainment.

The Garage studio theatre (Norwich) can seat up to 110 people in a range of different layouts. It can also be used for standing events and can accommodate up to 180 people.

The Platform Theatre (Norwich) is in the grounds of City College Norwich (CCN), and has a large stage with raked seating for an audience of around 200. The theatre plays host to performances by both student and professional companies.

The Sewell Barn Theatre (Norwich) is the smallest theatre in Norwich and has a seating capacity of 100. The auditorium features raked seating on three sides of an open acting space.

The Norwich Arts Centre (Norwich) theatre opened in 1977 in St. Benedict's Street, and has a capacity of 290.

The Princess Theatre (Hunstanton) stands overlooking the Wash and the green in the East Coast resort of Hunstanton. It is a 472-seat venue. Open all year round, the theatre plays host to a wide variety of shows from comedy to drama, celebrity shows to music for all tastes and children's productions. It has a six-week summer season plus an annual Christmas pantomime.

Sheringham Little Theatre (Sheringham) has seating for 180. The theatre programmes a variety of plays, musicals and music, and also shows films.

The Gorleston Pavilion (Gorleston) is an original Edwardian building with a seating capacity of 300, situated on the Norfolk coast. The theatre stages plays, pantomimes, musicals and concerts as well as a 26-week summer season.

Notable people from Norfolk

- Diana Athill, literary editor and author, South Norfolk and Ditchingham

- Peter Bellamy, folk singer and musician, who was brought up in North Norfolk

- Henry Blofeld, Cricket commentator

- Henry Blogg, the UK's most decorated lifeboatman, who was from Cromer

- Francis Blomefield, Anglican rector, early topographical historian of Norfolk

- James Blunt, English acoustic folk rock singer-songwriter who was raised in Norfolk during his childhood

- Boudica, scourge of the occupying Roman Army in first century Britain and queen of the Iceni, British tribe occupying an area slightly larger than modern Norfolk

- Martin Brundle, former motor-racing driver and now a commentator was born in King's Lynn

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton, writer, born at Heydon

- Dave Bussey, former BBC Radio 2 and current BBC Radio Lincolnshire presenter

- Howard Carter, archaeologist who discovered Tutankhamun's tomb; his childhood was spent primarily in Swaffham

- Edith Cavell, a nurse executed by the Germans for aiding the escape of prisoners in World War I

- Sam Claflin, actor, grew up in Norwich and studied at Costessey High School.

- Sam Clemmett, actor, from Brundall known for starring in West End stage play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, Haribo Tangfastics television advert and the BBC documentary Murder Games: The Life and Death of Breck Bednar where he played Breck Bednar the teen murdered by Lewis Daynes.[38]

- Edward Coke, 17th-century jurist and author of the Petition of Right was born in Mileham and educated at Norwich School

- Olivia Colman, actress, born and educated in Norfolk.

- Jamie Cutter, Co-founder of Cutter & Buck, America's largest golf apparel providers, born in Norwich

- Deaf Havana, Alternative rockband from the King's Lynn area.

- Cathy Dennis, singer and songwriter, from Norwich

- Diana, Princess of Wales, first wife of Charles, Prince of Wales, was born and grew up in Park House near the Sandringham estate

- Charles Spencer, 9th Earl Spencer brother of Diana, Princess of Wales and maternal uncle to T.R.H. Prince William, Duke of Cambridge and Prince Harry

- Anthony Duckworth-Chad, landowner and Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Norfolk

- Sir James Dyson, inventor and entrepreneur, was born at Cromer, grew up at Holt and was educated at Gresham's School

- Bill (1916–1986), Brian (1922–2009), Eric (1914–1993), Geoff (1918–2004), John (1937–), and Justin (1961–) Edrich, cricketers

- E-Z Rollers, Drum and bass group was formed in Norwich.

- Nathan Fake, electronic dance music producer/DJ

- Pablo Fanque, equestrian and popular Victorian circus proprietor, whose 1843 poster advertisement inspired The Beatles song, Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!, born in Norwich

- Natasha and Ralph Firman, racing drivers, were both born and brought up in Norfolk and educated at Gresham's School

- Caroline Flack, television presenter, who grew up in East Wretham and went to school in Watton

- Margaret Fountaine, butterfly collector, was born in Norfolk, and her collection is housed in Norwich Castle Museum

- Elizabeth Fry, prominent 19th century Quaker prison reformer pictured on the Bank of England £5 note, born and raised in Norwich

- Stephen Fry, actor, comedian, writer, producer, director and author who was born in London and was brought up in the village of Booton near Reepham. He now has a second home near King's Lynn.

- Samuel Fuller, signed the Mayflower Compact

- Claire Goose, actress who starred in Casualty, was raised in Norfolk

- Ed Graham, drummer of Lowestoft band The Darkness, was born in Great Yarmouth

- Sienna Guillory, actress, from north Norfolk, who was educated at Gresham's School

- Sir Henry Rider Haggard, novelist, author of She, King Solomon's Mines, born Bradenham 1856 and lived after his marriage at Ditchingham

- Jake Humphrey, BBC presenter, spent most of his childhood in Norwich

- Andy Hunt, footballer, grew up in Ashill.

- Julian of Norwich, mediaeval mystic, born probably in Norwich in 1342; lived much of her life as a recluse in Norwich

- Robert Kett, leader of Kett's Rebellion in East Anglia 1549, from Wymondham

- Sid Kipper, Norfolk humourist, author, songwriter and singer

- Myleene Klass, former Hear'Say singer, comes from Gorleston

- Holly Lerski, singer and songwriter, former member of the band Angelou, grew up and resides in Norfolk

- Henry Leslie, actor and playwright, born 1830 at Walsoken.

- Samuel Lincoln, ancestor of US President Abraham Lincoln

- Matthew Macfadyen, actor who starred in Spooks, was born in Great Yarmouth

- Kenneth McKee, surgeon who pioneered hip replacement surgery techniques, lived in Tacolneston

- Roger Taylor, drummer of the rock band Queen was born in King's Lynn and spent the early part of his childhood in Norfolk.

- Danny Mills, footballer, born in Norwich.

- Sir John Mills, actor, born in North Elmham

- Horatio, Lord Nelson, Admiral and British hero who played a major role in the Battle of Trafalgar, born and schooled in Norfolk.

- Nimmo Twins, sketch comedy duo well known in Norfolk

- King Olav V of Norway, born at Flitcham on the Sandringham estate

- Beth Orton, singer-songwriter, was born in Dereham and raised in Norwich.

- Thomas Paine, philosopher, born in Thetford.

- Ronan Parke, Britain's Got Talent 2011 finalist and runner up.

- Margaret Paston, author of many of the Paston Letters, born 1423, lived at Gresham.

- Barry Pinches, snooker player who comes from Norwich.

- Matthew Pinsent, Olympic champion rower, was born in Holt.

- Prasutagus, 1st-century king of the Iceni, who occupied roughly the area which is now Norfolk

- Philip Pullman, author, born in Norwich

- Miranda Raison, actress, from north Norfolk, who was educated at Gresham's School

- Anna Sewell, writer, author of Black Beauty, born at Great Yarmouth, lived part of her life at Old Catton near Norwich and buried at Lamas, near Buxton.

- Thomas Shadwell, playwright, satirist and Poet Laureate

- Allan Smethurst, 'The Singing Postman' who sang songs in his Norfolk dialect, was from Sheringham

- Hannah Spearritt, actress and former S Club 7 singer, who is from Gorleston

- Adam Thoroughgood, colonial leader in Virginia, namer of New Norfolk County, which later became Norfolk, Virginia.

- Peter Trudgill, sociolinguist specialising in accents and dialects including his own native Norfolk dialect, was born and bred in Norwich

- George Vancouver, born King's Lynn. Captain and explorer in the Royal Navy

- Stella Vine, English artist, spent many of her early years in Norwich

- Sir Robert Walpole, first Earl of Orford, regarded as the first British prime minister

- Tim Westwood, rap DJ and Radio 1 presenter, grew up in and around Norwich

- Parson Woodforde, 18th century clergyman and diarist

- Nick Youngs (1959–) and his two sons, Ben (1989–) and Tom (1987–) were both raised close to the town of Aylsham on their father's farm.[39] Youngs was a former rugby player for Leicester Tigers and England. Both sons went on to represent the national rugby union team.

People associated with Norfolk

The following people were not born or brought up in Norfolk but are long-term residents of Norfolk, are well known for living in Norfolk at some point in their lives, or have contributed in some significant way to the county.

- Verily Anderson, writer, lived in North Norfolk.

- Julian Assange, Australian publisher, journalist, writer, computer programmer, Internet activist and editor in chief of WikiLeaks, lived since 16 December 2010 in Ellingham Hall, the mansion of Vaughan Smith, under house arrest whilst fighting extradition to Sweden, before relocating to Kent in December 2011

- Peter Baker (1921–1966), British Conservative MP for South Norfolk

- Mary Bristow (1781–1805), landscape gardener, owner of Quidenham Hall

- Bill Bryson, writer, has lived in the county since 2003.

- Adam Buxton, comedian and one half of Adam and Joe, moved to Norfolk in 2008

- Richard Condon, Theatre Royal, Norwich and Pavilion Theatre, Cromer Pier manager

- Revd Richard Enraght, 19th century clergyman, religious controversialist, Rector of St Swithun, Bintree

- Liza Goddard TV and stage actress, lives in the village of Syderstone.

- Trisha Goddard, TV personality, lives in Norwich and writes a column in the local newspaper the Eastern Daily Press.

- Roderick Gordon, writer of Tunnels series, lives in North Norfolk.

- Adriana Hunter, translator of French novels, lives in Norfolk.

- John Major British Prime Minister from 1990 to 1997, has a holiday home in Weybourne.

- Alan Partridge, fictional tongue-in-cheek media personality portrayed by Steve Coogan. His feature film Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa was set, filmed and had its world premiere in Norwich in 2013.

- Pocahontas, who lived at Heacham Hall for part of her life when she was married to John Rolfe.

- Martin Shaw, stage, television and film actor, is based in Norfolk.

- Delia Smith, cookery writer and major Norwich City Football Club shareholder

- John Wilson, angler, writer and broadcaster

See also

- Duke of Norfolk

- Earl of Norfolk

- High Sheriff of Norfolk

- Custos Rotulorum of Norfolk – List of Keepers of the Rolls

- Norfolk (UK Parliament constituency) – List of MPs for the Norfolk constituency

- List of places in Norfolk

- List of future transport developments in the East of England

- List of Parliamentary constituencies in Norfolk

- Norfolk Terrier

- Norwich Terrier

- Recreational walks in Norfolk

- Royal Norfolk Regiment

- Healthcare in Norfolk

- Norfolk Police

- Norfolk Police and Crime Commissioner

References

- ↑ Recorded in wills of 1043–45: Ekwall, Eilert (1940) The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names; 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press; p. 327 citing Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. Anglo-Saxon Wills. Cambridge, 1930

- ↑ "Norfolk 2017-2018". The High Sheriffs Association of England and Wales. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ↑ "Population and demography overview". Norfolk Insight. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- 1 2 "2011 Census – Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ↑ "Broads Authority Act 2009 — UK Parliament". Services.parliament.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Homepage - Broads Authority". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ "Medieval Churches in Norfolk :: Geograph Britain and Ireland". Geograph.org.uk. 24 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ "Voices of the Powerless: Boils and Buboes". BBC Radio 4. 29 August 2002. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ↑

- ↑ "Shoreline Management Plan". north-norfolk.org. 22 February 2008. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- ↑ Elliott, Valerie (29 March 2008). "Climate change: surrender a slab of Norfolk, say conservationists". The Times. London. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ↑ Office for National Statistics, 2001. Regional Trends 26 ch:14.7 (PDF). Accessed 3 January 2006.

- ↑ "Home". Norfolk Saffron. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ "Welcome to Locate Norfolk " Locate:Norfolk". Investinnorfolk.com. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- 1 2 "UCS Great Yarmouth". Web.archive.org. 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ "Norfolk council results". BBC News. 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "Local Government White Paper, Strong and Prosperous Communities". Norfolk County Council. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ↑ "The business case for unitary Norwich". Norwich City Council. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Proposals for future unitary structures: Stakeholder consultation". Communities and Local Government. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Our advice to the Secretary of State on unitary local government in Norfolk (PDF Document)" (PDF). The Boundary Committee. 7 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012.

- ↑ "Minister's Statement of 10 February 2010". Communities and Local Government. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Unitary Authorities". House of Commons Hansard Debates. Parliament of the United Kingdom. 24 February 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Reaction to announcement on Local Government Reorganisation Announcement". News Archive. Norfolk County Council. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ↑ "Peter Housden's letter in full". Eastern Daily Press. 12 February 2010.

- ↑ Shaun Lowthorpe (2 February 2010). "At last, a verdict on Norfolk councils' future". Eastern Daily Press.

- ↑ Lowthorpe, Shaun (14 May 2010). "Government chief moves to axe Norwich unitary plans". Eastern Daily Press.

- ↑ "Pickles stops unitary councils in Exeter, Norwich and Suffolk". Department for Communities and Local Government. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ↑ "New bid to end unitary plans". Yarmouth Mercury. 17 May 2010.

- ↑ "September by-elections for Exeter and Norwich". BBC News. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ↑ "FOND Norfolk Dumplings Page". Norfolkdialect.com. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ "Norfolk Dumpling (Grose 1811 Dictionary)". Fromoldbooks.org. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ "Health | Doctor slang is a dying art". BBC News. 18 August 2003. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Cawley, Laurence; News, Jodie Smith BBC. "Normal for Norfolk: Where did the phrase come from?". BBC News. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ "Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and Devon: A Complete Tour Guide and Companion by Brian W Pugh, Paul R Spiring and Sadru Bhanji – TheBookbag.co.uk book review". Thebookbag.co.uk. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ ''The District Messenger''. (PDF) . Retrieved on 25 August 2011.

- ↑ "Seating Plan » Maddermarket Theatre". maddermarket.co.uk. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "Sam Clemmett". IMDb. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Norfolk, England. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Norfolk (England). |

- Norfolk at DMOZ

- Official Visitor site for the East of England

- East of England Tourism

- Eastern Daily Press – Norfolk Newspaper

- Norfolk County Council

- Norfolk tourism (official site)

- Norfolk Tourist Information & Articles

- Norfolk Tourist Information

- "60 Years of Change". A digital story, telling of the changes in a village school in rural Norfok

- Photos of Norfolk

- Norfolk Rural Community Council, supports communities across Norfolk

- Norfolk E-Map Explorer – historical maps and aerial photographs of Norfolk

- Gallery of Norfolk – Photographs of Norfolk

- Photographs of North Norfolk

- Norfolk Record Office – Government agency that collects and preserves records of historical significance for Norfolk and makes them publicly accessible – useful for genealogical research

- Norfolk County Council YouTube channel

- Images of Norfolk at the English Heritage Archive

Coordinates: 52°40′N 1°00′E / 52.667°N 1.000°E