Nordic agrarian parties

The Nordic agrarian parties, or Nordic Centre parties, are agrarian political parties that belong to a political tradition particular to the Nordic countries. Positioning themselves in the centre of the political spectrum, but fulfilling roles distinctive to Nordic countries, they remain hard to classify by conventional political ideology.

These parties are non-socialist and typically combine a commitment to small businesses, political decentralisation, environmentalism and, at times, scepticism towards the European Union. The parties have divergent views on the free market. Internationally, they are most commonly aligned to the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) and the Liberal International.

Historically a farmers' party, a declining farmer population after the Second World War made them broaden their scope to other issues and sections of society. At this time three of them renamed themselves to Centre Party, with Finnish Centre Party being the last to do so, in 1965.[1] Now, the main agrarian parties are the Centre Party in Sweden, Venstre in Denmark, Centre Party in Finland, Centre Party in Norway and Progressive Party in Iceland.

History

Compared to continental Europe, the peasants in the Nordic countries historically had an unparalleled degree of political influence, being not only independent but also represented as the fourth estate in the national diets, like in the Swedish Riksdag of the Estates. The agrarian movement thus precedes the labour movement by centuries in Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Norway.

The first of the parties, Venstre in Denmark, was formed as a liberal, anti-tax farmers' party in 1870. The rest of the parties emerged in the early 20th century, spurred by the introduction of universal suffrage and proportional representation across the region.[2] Finland's Agrarian League was the first to be created in 1906, followed by the Agrarian Party in Norway in 1915. Sweden's Agrarian Party, founded in 1921, emerged from the existing Lantmanna Party, and its splinter groups.[2]

As the Scandinavian farming population declined, the parties moved towards becoming catch-all centrist parties by capturing some of the urban electorate.[3] The Swedish Agrarian Party renamed itself to the Centre Party in 1958. The Norwegian and Finnish parties adopted the same name in 1959 and 1965 respectively.[3]

After the end of Soviet rule in the Baltic countries, the Estonian Centre Party (established in 1991) and Lithuanian Centre Union (1993) were modelled explicitly on the Swedish example.[4] The Latvian Farmers' Union of the post-communist era views the Nordic agrarian parties as models, too, aiming to be a centrist catch-all party instead of a pure single-interest party of farmers.[5]

Ideology

The parties' attitudes to the free market and economic liberalism are mixed. Whereas the Norwegian Centre Party and Icelandic Progressive Party are opposed to economic liberalisation,[6] the others, most notably the Danish Venstre, are pro-market and put a heavy emphasis on economic growth and productivity.[7] Because of this divide, Venstre are described in some academic literature as the separate 'half-sister' of the Nordic agrarian parties.[3] Nonetheless, all of the parties define themselves as 'non-socialist', while also distancing themselves from the label of 'bourgeois' (borgerlig), which is reserved for the conservative and liberal parties.[3]

Most of the parties have traditionally sat on the Eurosceptic side in their respective countries.[8][9] However, for the most part, they hold these positions due to particular policies, with an emphasis on whether they believe European policies to be better or worse for rural communities.

The Centre Party in Norway is the party most opposed to European Union membership, having maintained that position since the 1972 referendum. The Icelandic Progressives, historically opposed to membership, changed their position to pro-accession in January 2009. The Danish Venstre is also in favour of the European Union and Denmark's entry into the Eurozone.

Political support

While originally supported by farmers, the parties have adapted to declining rural populations by diversifying their political base. The Finnish Centre Party receives only 10% of its support from farmers, while Venstre received only 7% of their votes from farmers in 1998.[10]

Parties

The Centre parties in Sweden, Finland, Norway, Åland, Estonia, Poland and Lithuania have similar backgrounds and identities, as indicated by their similar logos, based on the four-leaf clover

The current Nordic agrarian parties are:

-

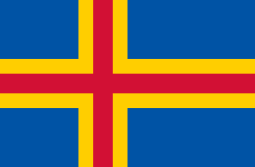

Åland Islands: Åland Centre[11]

Åland Islands: Åland Centre[11] -

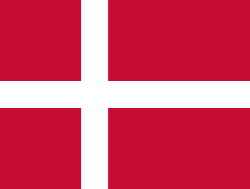

Denmark: Venstre[12]

Denmark: Venstre[12] -

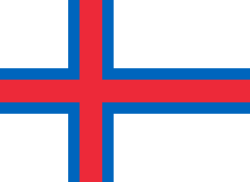

Faroe Islands: Union Party[13]

Faroe Islands: Union Party[13] -

Finland: Centre Party[12][14]

Finland: Centre Party[12][14] -

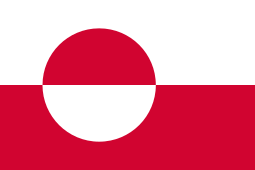

Greenland: Atassut

Greenland: Atassut -

Iceland: Progressive Party[11][14]

Iceland: Progressive Party[11][14] -

Norway: Centre Party,[11][15] Coastal Party

Norway: Centre Party,[11][15] Coastal Party -

Sweden: Centre Party[11][12][15]

Sweden: Centre Party[11][12][15]

Historical agrarian parties include:

-

Denmark: Farmers' Party[14]

Denmark: Farmers' Party[14] -

Finland: Finnish Rural Party,[11] Small Peasants' Party of Finland, Small Farmers' Party of Finland, Finnish People's Unity Party

Finland: Finnish Rural Party,[11] Small Peasants' Party of Finland, Small Farmers' Party of Finland, Finnish People's Unity Party -

Iceland: Farmers' Party (1912), Farmers' Party (Iceland, 1933), Independent Farmers

Iceland: Farmers' Party (1912), Farmers' Party (Iceland, 1933), Independent Farmers -

Lithuania: Liberal and Centre Union, Lithuanian Centre Union

Lithuania: Liberal and Centre Union, Lithuanian Centre Union -

Norway: Centre

Norway: Centre -

Sweden: Lantmanna Party

Sweden: Lantmanna Party

The current similar agrarian parties are:

-

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Croatian Peasant Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Croatian Peasant Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina -

Croatia: Croatian Peasant Party, Croatian Democratic Peasant Party

Croatia: Croatian Peasant Party, Croatian Democratic Peasant Party -

Estonia: Estonian Centre Party

Estonia: Estonian Centre Party -

Latvia: Latvian Farmers' Union[16]

Latvia: Latvian Farmers' Union[16] -

Lithuania: Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union,[17] Lithuanian Freedom Union, Lithuanian Centre Party

Lithuania: Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union,[17] Lithuanian Freedom Union, Lithuanian Centre Party -

Poland: Polish People's Party[18][19][20]

Poland: Polish People's Party[18][19][20] -

Switzerland: Democratic Union of the Centre[21][22]

Switzerland: Democratic Union of the Centre[21][22]

See also

Bibliography

- Arter, David (1999). Scandinavian Politics Today. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5133-3.

- Arter, David (2001). From Farmyard to City Square?: the Electoral Adaptation of the Nordic Agrarian Parties. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-7546-2084-6.

- Esaiasson, Peter; Heidar, Knut (1999). Beyond Westminster and Congress: the Nordic Experience. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-0839-7.

- Hilson, Mary (2008). The Nordic Model: Scandinavia Since 1945. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-1-86189-366-6.

- Ruostetsaari, Ilkka (2007). Cotta, Maurizio; Best, Heinrich, eds. Restructuring of the European Political Centre: Withering Liberal and Persisting Agrarian Party Families. Democratic Representation in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–252. ISBN 978-0-19-923420-2.

- Siaroff, Alan (2000). Comparative European Party Systems: an Analysis of Parliamentary Elections. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-2930-5.

References

- ↑ Arter (1999), p. 78

- 1 2 Arter (1999), p. 76

- 1 2 3 4 Ruostetsaari (2007). Restructuring of the European Political Centre. p. 226.

- ↑ Arter (2001). From Farmyard to City Square?. p. 181.

- ↑ Nissinen, Marja (1999). Latvia's Transition to a Market Economy: Political Determinants of Economic Reform Policy. Macmillan. p. 128.

- ↑ Siaroff (2000), p. 295

- ↑ Narud, Hanne Marthe; Valen, Henry (1999). Esaiasson; Heidar, eds. What Kind of Future and Why?: Attitudes of Voters and Representatives. Beyond Westminster and Congress: the Nordic Experience. p. 377.

- ↑ Sitter, Nick (2003). "Euro-Scepticism as Party Strategy: Persistence and Change in Party-Based Opposition to European Integration". Austrian Journal of Political Science. 32 (3): 239–53.

- ↑ Hanley, David L. (2008). Beyond the Nation State: Parties in the Era of European Integration. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-0795-0.

- ↑ Ruostetsaari (2007). Restructuring of the European Political Centre. p. 227.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christina Bergqvist (1999). "Appendix II". In Christina Bergqvist. Equal Democracies?: Gender and Politics in the Nordic Countries. Nordic Council of Ministers. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-82-00-12799-4.

- 1 2 3 Anders Nordlund (2005). "Nordic social politics in the late twentieth century". In Nanna Kildal; Stein Kuhnle. Normative Foundations of the Welfare State: The Nordic Experience. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-134-27283-9.

- ↑ Parties and Elections in Europe: The database about parliamentary elections and political parties in Europe, by Wolfram Nordsieck

- 1 2 3 Daniele Caramani (2004). The Nationalization of Politics: The Formation of National Electorates and Party Systems in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-521-53520-5.

- 1 2 Nik Brandal; Øivind Bratberg; Dag Einar Thorsen (2013). The Nordic Model of Social Democracy. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-137-01327-9.

- ↑ "Parties and Elections in Europe, "Latvia", The database about parliamentary elections and political parties in Europe, by Wolfram Nordsieck". Parties & Elections. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Nordsieck, Wolfram. "Parties and Elections in Europe".

- ↑ Jennifer Lees-Marshment (2 July 2009). Political Marketing: Principles and Applications. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-134-08411-1.

- ↑ Paul G. Lewis (2000). Political Parties in Post-Communist Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-415-20182-7. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ↑ Igor Guardiancich (21 August 2012). Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe: From Post-Socialist Transition to the Global Financial Crisis. Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-136-22595-6.

- ↑ Svante Ersson; Jan-Erik Lane (28 December 1998). Politics and Society in Western Europe. SAGE. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-0-7619-5862-8. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Aleks Szczerbiak; Paul Taggart (2008). Opposing Europe?: The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism: Volume 2: Comparative and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-19-925835-2.