Noongar

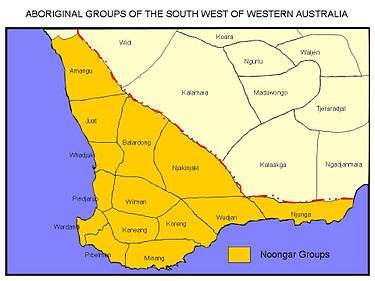

The Noongar (/ˈnʊŋɑː/; alternatively spelt Nyungar, Nyoongar, Nyoongah, Nyungah, or Noonga[1]) are an Indigenous Australian people who live in the south-west corner of Western Australia, from Geraldton on the west coast to Esperance on the south coast. Traditionally, they inhabit the region from Jurien Bay to the southern coast of Western Australia, and east to what is now Ravensthorpe and Southern Cross, south west of the circumcision line separating those Aboriginal groups of central Australia that practised male circumcision upon initiation from those who did not. Noongar country, according to Norman Tindale, was occupied by 14 different groups: Amangu, Ballardong, Yued, Kaneang, Koreng, Mineng, Njakinjaki, Njunga, Pibelmen, Binjareb, Wardandi, Whadjuk, Wilman and Wudjari. The Noongar traditionally spoke dialects of the Noongar language, a member of the large Pama-Nyungan language family, but generally today speak Australian Aboriginal English (a dialect of the English language) combined with Noongar words and grammar. Although Noongar today still recognise the existence of these groups, most Noongar today trace their ancestry to more than one of these groups.

History

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Noongar population has been variously estimated at between 6,000 and some tens of thousands. Colonisation by the British resulted in both violence and new diseases, taking a heavy toll on the population.[2] The 2001 census figures showed that 21,000 people identified themselves as indigenous in the south-west of Western Australia. In 2004, the community claimed to number over 28,000 people.[3] Today, most of the Noongar live in the Perth Metropolitan Region.[4] By 2016, the Swan Valley Noongar Community estimated the number of Noongars to be 46,000.

Traditional Noongar people made a living by hunting and trapping a variety of game, including kangaroos, possums and wallabies; by fishing using spears and fish traps; as well as by gathering an extensive range of edible wild plants, including wattle seeds. Nuts of the zamia palm were something of a staple food, though it required extensive treatment to remove its toxicity, and for women may have had a contraceptive effect. Noongar people utilised quartz, replacing chert flint for spear and knife edges from 12,000 years ago, when the chert deposit was submerged by sea level rise during the Flandrian transgression.

The Noongar people saw the arrival of Europeans as the returning of deceased people. As they approached from the west, they called the newcomers Djanga (or djanak), meaning "white spirits".[5][6] There were a number of reasons for this. Firstly their white complexion reminded the Noongar of corpses; their unclean odour of early 19th century Europeans was said to resemble the dead; the fact that the ships arrived from the west, the direction of Kuranup, the setting sun location of the soul in traditional beliefs;[7] the fact that Europeans seemed to have no memory of kinship relations; and that Noongars who associated closely with Europeans were apt to die from European diseases over which Aboriginal people had little resistance, supported this claim.

Yagan arose as one of a number of leaders of the Noongar at the time when British settlers first arrived in the Swan River area in 1829 and Captain James Stirling declared that the local tribes were British subjects. Although at first the Noongar traded amicably with the settlers, rifts and misunderstandings developed as land seizures went on, and attacks and reprisal attacks soon escalated. An example of such misunderstandings was the Noongar land-management practice of setting fires in early summer, mistakenly seen as an act of hostility by the settlers. Conversely, the Noongar saw the settlers' livestock as fair game to replace the dwindling stocks of native animals shot indiscriminately by settlers. Yagan participated in a number of food raids and in killing settlers in retaliation for the deaths of Noongar at white hands – notably, he warned nearby whites repeatedly that one white life would be taken for every Noongar killed by a white. He was shot by a shepherd boy and is now considered by many to have been one of the first indigenous resistance fighters.[8] Matters escalated with conflicts between the settlement of Thomas Peel and the Binjareb people, resulting in the Pinjarra massacre. Similarly struggles with Balardong people in the Avon Valley continued until "pacified" by Lieutenant Henry William St Pierre Bunbury.

From August 1838 ten Aboriginal prisoners were sent to Rottnest Island (known as Wadjemup to the Noongar, possibly meaning "place across the water"[9]). After a short period when both settlers and prisoners occupied the island, the Colonial Secretary announced in June 1839 that the island would become a penal establishment for Aboriginal people and, between 1838 and 1931, Rottnest Island was used as a prison to transfer Aboriginal prisoners "overseas". To "pacify" the Aboriginal population, men were rounded up and chained for offences ranging from spearing livestock, burning the bush or digging vegetables on what had been their own land. It has been estimated that there may be as many as 369 Aboriginal graves on the island, of which five were for prisoners who were hanged. Except for a short period between 1849 and 1855, during which the prison was closed, some 3,700 Aboriginal men and boys, many of them Noongars, but also many others from all parts of the state, were imprisoned.[10]

A significant development for the Noongar People in the Western Australian Colony was the arrival of Rosendo Salvado in 1846. Bishop Salvado was a Benedictine monk from the Spanish region of Galicia, who was a gifted musician, highly cultured but at the same time very caring, practical and down to earth. Bishop Salvado would dedicate his life to the humane treatment of the Australian Aboriginals at the mission he created at New Norcia and always did his utmost to assist the Australian Aboriginals adjust to the challenges of British settlement. In the early part of the Colony New Norcia could be described as a beacon of hope in a sea of despair for the Noongar people. Bishop Salvado brought many Benedictine monks to New Norcia to assist him build the mission and assist the Australian Aboriginal at the mission. Bishop Salvado was many decades ahead of his time in his pioneering of a humanitarian approach to bringing western civilization to the Aboriginal people at New Norcia by teaching them life skills required to survive in the rapidly growing British settlement but at the same time encouraging them to maintain their own culture. The Aboriginal people were free to come and go from the mission as they chose. Bishop Salvado saw no lack of innate ability in the Aboriginal people but he understood that they needed time to adjust to the new ways of the British settlers. The Aboriginal people were also not the only people to benefit from Bishop Salvado, the success and indeed the very survival of the Catholic Church in the early days of the Western Australian settlement would owe much to Bishop Salvado, although this was always his secondary consideration to the Australian Aboriginal.[11]

From 1890 to 1958, the lives and lifestyles of Noongar people were subject to the Native Welfare Act. Two state-run "concentration" camps,[12] Moore River Native Settlement and Carrolup (later known as Marribank), became the home of up to one-third of the population. It is estimated that 10 to 25% of Noongar children were forcibly "adopted" during these years, in part of what has become known as the Stolen Generations.[13]

Language

The Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages website states that out of thirteen dialects spoken by the Noongar people at the time of European settlement, only five still remain.[14] The word "Noongar" can be roughly translated into English as "human being".

Culture

Noongar people live in many country towns throughout the south-west as well as in the major population centres of Perth, Mandurah, Bunbury, Geraldton, Albany and Esperance. Many country Noongar people have developed long-standing relationships with wadjila (white fella[man]) farmers and continue to hunt kangaroo and gather bush tucker (food) as well as to teach their children stories about the land. In a few areas in the south-west, visitors can go on bushtucker walks, trying foods such as kangaroo, emu, quandong jam or relish, bush tomatoes, witchetty grub pâté and bush honey.

In Perth, the Noongar believe that the Darling Scarp is said to represent the body of a Wagyl, a snakelike being from the Dreamtime that meandered over the land creating rivers, waterways and lakes. It is thought that the Wagyl created the Swan River. The Wagyl has been associated with Wonambi naracoutensis, part of the extinct megafauna of Australia that disappeared between 15 and 50,000 years ago.

Also in Perth, Mount Eliza was an important site for the Noongar. It was a hunting site where kangaroos were herded and driven over the edge to provide meat for gathering clans. In this context, the "clan" is a local descent group – larger than a family but based on family links through a common ancestry. At the base of Mount Eliza is a sacred site where the Wagyl is said to have rested during its journeys. This site is also the location of the former Swan Brewery which has been a source of contention between local Noongar groups (who would like to see the land, which was reclaimed from the river in the late 19th century, "restored" to them) and the title-holders who wished to develop the site. A Noongar protest camp existed here for several years in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Noongar culture is particularly strong with the written word. The plays of Jack Davis are on the school syllabus in several Australian states. Davis' first full-length play Kullark, a documentary on the history of Aboriginals in WA, was first produced in 1979. Other plays include: No Sugar, The Dreamers, Barungin: Smell the Wind, In Our Town and for younger audiences, Honey Spot and Moorli and the Leprechaun. Kim Scott won the 2000 Miles Franklin Award for his novel Benang and the 2011 award for That Deadman Dance.

Yirra Yaakin[15] describes itself as the response to the Aboriginal Community’s need for positive self-enhancement through artistic expression. It is a theatre company which strives for community development and which also has a drive to create "exciting, authentic and culturally appropriate indigenous theatre".

The Barnett government of Western Australia announced in November 2014 that, due to changes in funding arrangements with the Abbott Federal government, it was closing 150 of 276 Aboriginal communities in remote locations. As a result Noongars in solidarity with other Aboriginal groups established a refugee camp on Heirisson Island. Despite police action to dismantle the camp twice in 2015, the camp continues into February 2016.

Despite such state government actions many local governments in the south-west have developed "compacts" or "commitments" with their local Noongar communities to ensure that sites of significance are protected and that the culture is respected. At the same time, the Western Australian Barnett government, also from November 2014, had been forcing the Aboriginal Cultural Material Committee to deregister 300 Aboriginal sacred sites in Western Australia.[16][17] Although falling most heavily upon Pilbara and Kimberley sites this government policy also was having an impact upon Noongar lands according to Ira Hayward-Jackson, Chairman of the Rottnest Island Deaths Group.[18] The changes also removed rights of notification and appeal for traditional owners seeking to protect their heritage. A legal ruling on 1 April 2015 overturned the government's actions on some of the sites deregistered which were found to be truly sacred.

Elders are increasingly asked on formal occasions to provide a "Welcome to Country" and the first steps of teaching the Noongar language in the general curriculum have been made.

In recent years there has been considerable interest in Noongar visual arts. In 2006, Noongar culture was showcased as part of the Perth International Arts Festival. A highlight of the Festival was the unveiling of the monumental 'Ngallak Koort Boodja – Our Heart Land Canvas'. The 8-metre canvas was commissioned for the festival by representatives of the united elders and families from across the Noongar nation. It was painted by leading Noongar artists Shane Pickett, Tjyllyungoo (Lance Chadd), Yvonne Kickett, Alice Warrell and Sharyn Egan.

Noongar ecology

The Noongar people occupied and maintained the Mediterranean climate lands of the south-west of Western Australia, and made sustainable use of seven biogeographic regions of their territory, namely;

- Geraldton Sandplains – Amangu and Yued

- Swan Coastal Plain – Yued, Whadjuk, Binjareb and Wardandi

- Avon Wheatbelt – Balardong, Nyakinyaki, Wilman

- Jarrah Forest – Whadjuk, Binjareb, Balardong, Wilman, Ganeang

- Warren – Bibulmun, Mineng

- Mallee – Wilmen, Goreng and Wudjari

- Esperance Plains – Njunga

These seven regions have been acknowledged as a biodiversity hot-spot,[19] having a generally greater number of endemic species than most other regions in Australia. The ecological damage done to this region through clearing, introduced species, by feral animals and non-endemic plants is also severe, and has resulted in a high proportion of plants and animals being included in the categories of rare, threatened and endangered species. In modern times many Aboriginal men were employed intermittently as rabbiters, and rabbit became an important part of Noongar diet in the early 20th century. The Noongar territory also happens to conform closely with the South-west Indian Ocean Drainage Region, and the use of these water resources played a very important seasonal part in their culture.

The Noongar thus have a close connection with the earth and, as a consequence, they divided the year into six distinct seasons that corresponded with moving to different habitats and feeding patterns based on seasonal foods.[20] They were:

- Birak (December/January)—Dry and hot. Noongar burned sections of scrubland to force animals into the open for easier hunting.

- Bunuru (February/March)—Hottest part of the year, with sparse rainfall throughout. Noongar moved to estuaries for fishing.

- Djeran (April/May)—Cooler weather begins. Fishing continued and bulbs and seeds were collected for food.

- Makuru (June/July)—Cold fronts that have until now brushed the lower south-west coast begin to cross further north. This is usually the wettest part of the year. Noongar moved inland to hunt, once rains had replenished inland water resources.

- Djilba (August/September)—Often the coldest part of the year, with clear, cold nights and days, or warmer, rainy and windy periods. As the nights begin to warm up there are more clear, sunny days. Roots were collected and emus, possums and kangaroo were hunted.

- Kambarang (October/November)—A definite warming trend is accompanied by longer dry periods and fewer cold fronts crossing the coast. The height of the wildflower season. Noongar moved towards the coast where frogs, tortoises and freshwater crayfish were caught.

Native title

On 19 September 2006 the Federal Court of Australia brought down a judgment which recognised native title in an area over the city of Perth and its surrounds, known as Bennell v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243.[21] An appeal was subsequently lodged and was heard in April 2007. The remainder of the larger "Single Noongar Claim" area, covering 193,956 km² of the south-west of Western Australia, remains outstanding, and will hinge on the outcome of this appeal process. In the interim, the Noongar people together will continue to be involved in native title negotiations with the Government of Western Australia, and are represented by the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council.

Justice Wilcox's judgment is noteworthy for several reasons. It highlights Perth's wealth of post-European settlement writings which provide an insight into Aboriginal life, including laws and customs, around the time of settlement in 1829 and also into the beginning of the last century. These documents enabled Justice Wilcox to find that laws and customs governing land throughout the whole Single Noongar Claim (taking in Perth, and many other towns in the greater South West) were those of a single community. The claimants shared a language and had extensive interaction with others in the claim area.

Importantly, Justice Wilcox found the Noongar community constituted a united society which had continued to exist despite the disruption resulting from mixed marriage and people being forced off their land and dispersed to other areas as a result of white settlement and later Government policies.

In April 2008 the Full Bench of the Federal Court upheld parts of the appeal by the Western Australian and Commonwealth governments against Justice Wilcox's judgment.

Other native title claims on Noongar lands include:

- Gnaala Karla Booja: the headwaters of the Murray and Harvey Rivers to the Indian Ocean

- The Harris Family: The coasts of the area from Busselton to Augusta

- The South West Boojarah: Lower course of the Blackwood and adjacent coastal areas

- Southern Noongar Wagyl Kaip: The South Coast to the Blackwood Tributaries

- The Ballardong Lands: The interior Wheatbelt.

Economics

Since the Noongar are largely urbanised or concentrated in major regional towns studies have shown that the direct economic impact of the Noongar community on the WA economy was estimated to range between five and seven hundred million dollars per year.[22] Exit polls of tourists leaving Western Australia have consistently shown that "lack of contact with indigenous culture" has been their greatest regret. It has been estimated that this results in the loss of many millions of dollars worth of foregone tourist revenue.[23]

Current issues

As a consequence of the Stolen Generations and problems integrating with modern westernised society, many difficult issues face the present day Noongar. For example, the Noongar Men of the SouthWest gathering in 1996 identified major community problems associated with cultural dispossession such as:

- Alcohol and drugs (chemical dependencies, comorbidities or dual diagnoses, self medicating without medical supervision, solvent sniffing)

- Diet and nutrition

- Language and culture

- Domestic violence

- Father-and-son relationships

Many of these issues are not unique to the Noongar but in many cases they are unable to receive appropriate government-agency care. The report that was produced after this gathering also stated that Noongar men have a life expectancy of 20 years less than non-Aboriginal men, and go to hospital three times more often.[24]

The Noongar still have large extended families and many families have difficulty accessing available structures of sheltered housing in Western Australia. The Western Australian government has dedicated several areas for the purpose of building communities specifically for the Noongar people, such as the Swan Valley Noongar Community.

The Noongar themselves are tackling their own issues, for example, the Noongar Patrol, which is an Aboriginal Advancement Council initiative. It was set up to deter Aboriginal young people from offending behaviour and reduce the likelihood of their contact with the criminal justice system. Most people in Perth would associate this with patrols run in the entertainment hotspot Northbridge. The patrol uses mediation and negotiation with indigenous youth in an attempt to curb anti-social and offending behaviour of young people who come into the city at night.[25]

Notable Noongar people

Modern day

Historical

See also

Other Australian Aboriginal groups

- Anangu, in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory

- Koori, in New South Wales and Victoria

- Murri (people), in southern Queensland

- Nunga, in southern South Australia

- Palawah, in Tasmania.

References

- ↑ Norman Barnett Tindale South Australia Museum. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ↑ "Noongar history and culture" (PDF). South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2006.

- ↑ "Commitment to a New Relationship". South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council. Archived from the original on 20 October 2004.

- ↑ "Nyoongar Health Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012 – via Health Department of Western Australia.

- ↑ Moore, G. F. (1842). "Djăndga". A Descriptive Vocabulary of the Language in Common Use Amongst the Aborigines of Western Australia.

- ↑ Clarke, Philip A. (August 2007). "Indigenous Spirit and Ghost Folklore of "Settled" Australia". Folklore. Folklore Enterprises, Ltd. 118 (2): 141–161. JSTOR 30035418. doi:10.1080/00155870701337346.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy (1937). The Passing of the Aborigines – via The University of Adelaide.

- ↑ Cormick, Craig. "Yagan: an Aboriginal resistance hero". Green Left Weekly. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ↑ "Wadjemup (Rottnest Island)". www.creativespirits.info. Retrieved 24 January 2007.

- ↑ Green, Neville, & Moon, Susan (1997), "Far From Home: Aboriginal Prisoners of Rottnest Island, 1838–1931" (Perth)

- ↑ Russo, George (1980), Lord abbot of the wilderness : the life and times of Bishop Salvado, The Polding Press

- ↑ "Heritage Library". Retrieved 10 June 2001.

- ↑ Haebich, Anna & Delroy, Anne (1999) "The Stolen Generations – the separation of Aboriginal Children from their Families in Western Australia", (Western Australian Museum)

- ↑ "Language of the month series (number 11)". Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages. December 2000. Archived from the original on 4 December 2002. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ↑ Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- ↑ Callinan, Tara (presenter); Quartermaine, Craig (reporter) (14 April 2015). "WA Whistleblower 1 : Allegations of Bullying, Intimidation in WA Dept of Aboriginal Affairs". NITV News. Retrieved 10 July 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "WGAR News: WA Government Deregisters World's Oldest Rock Art Collection As Sacred Site: Amy McQuire, New Matilda". Indymedia Australia. 9 May 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ McMahon, Kristy (24 March 2015). "WA Government 'moving to deregister sacred sites'". National Indigenous Radio Service. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ "Biodiversity Hotspots – Australia – Overview". Conservation International. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006.

- ↑ "Noongar Seasons". Quaalup Homestead Wilderness Retreat. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ "Bennell v Western Australia [2006] FCA 1243 (19 September 2006)". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Ord, Duncan (19 June 2006). "A Study of the Impact of the Noongar Community on the Western Australian Economy"

. The University of Western Australia. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

. The University of Western Australia. Retrieved 20 September 2006. - ↑ "Executive Summary" (PDF). Tourism Western Australia. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ↑ "Closing the gap - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples". Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ "Home". Nyoongar Patrol. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

Published sources

- Jennie Buchanan, Len Collard, Ingrid Cumming, David Palmer, Kim Scott, John Hartley 2016. Kaya Wandjoo Ngala Noongarpedia. Special issue of Cultural Science Journal Vol 9, No 1.

- Green, Neville, Broken spears: Aborigines and Europeans in the Southwest of Australia, Perth: Focus Focus Education Services, 1984. ISBN 0-9591828-1-0

- Haebich, Anna, For Their Own Good: Aborigines and Government in the South West of Western Australia 1900–1940, Nedlands: University of Western Australia Press, 1992. ISBN 1-875560-14-9.

- Douglas, Wilfrid H. The Aboriginal Languages of the South-West of Australia, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1976. ISBN 0-85575-050-2

- Tindale, N.B., Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits and Proper Names, 1974.

External links

| Noongar Language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- AusAnthrop – Resources for Research

- Noongar Knowledge

- South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Council website.

- Web-site on the Indigenous People of Australia.

- Culture, Race and Identity: Australian Aboriginal Writing(pdf)

- Designing a Virtual Reality Nyungar Dreamtime Landscape Narrative (pdf)

- Noongar (Nyungar) Language Resources

- Orthography used in the Noongar Dictionary

- Bennell v State of Western Australia (re Noongar land claim)

- West Australian Government history of Noongar in the South West