Noctuidae

| Owlet moths | |

|---|---|

_Ear_Moth_(Amphipoea_oculea)_(20089467344).jpg) | |

| Amphipoea oculea | |

.jpg) | |

| Panthea coenobita | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Superfamily: | Noctuoidea |

| Family: | Noctuidae Latreille, 1809 |

| Type species | |

| Noctua pronuba | |

| Subfamilies | |

|

Acontiinae | |

| Diversity | |

| About 11,772 | |

The Noctuidae, commonly known as Owlet moths, cutworms or armyworms, is the most controversial family in the superfamily Noctuoidea because many of its clades are constantly changing, along with the other families of Noctuoidea.[1][2][3] It was considered the largest family in Lepidoptera for a long time, but after regrouping Lymantriinae, Catocalinae and Calpinae within the family Erebidae, the latter holds this title now.[4] Currently, Noctuidae is the second largest family in Noctuoidea, with about 1,089 genera and 11,772 species.[5] However, this classification is still contingent, as more changes continue to appear between Noctuidae and Erebidae.

Description

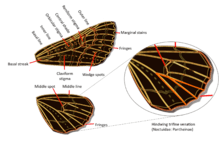

Adult: Most noctuid adults have drab wings, but some subfamilies such as Acronictinae and Agaristinae are very colorful, especially those form tropical regions (e.g. Baorisa hieroglyphica). They are characterized by a structure in the metathorax called the nodular sclerite or epaulette, which separates the tympanum and the conjunctiva in the tympanal organ. It functions to keep parasites (Acari) out of the tympanal cavity. Another characteristic in this group is trifine hindwing venation, by reduction or absence of the second medial vein (M2).[6]

Larva: Commonly green or brown; however, some species present bright colors, such as the Camphorweed cucullia moth (Cucullia alfarata). Most are pudgy and smooth with rounded short heads and few setae, but there are some exceptions in some subfamilies (e.g. Acronictinae and Pantheinae).[7]

Pupa: The pupae most often range from shiny brown to dark brown. When they newly pupate they are bright brownish orange, but after a few days start to get darker.

Eggs: Vary in colors, but all have a spherical shape.

Etymology

The word Noctuidae is derived from the name of the type genus Noctua which is from the Latin word Noctudæ for “Owl,” and the patronymic suffix -idae used typically to form taxonomic family names in animals.[8]

The common word “owlet” to refers a small or young owl. Otherwise, the terms “armyworms” and “cutworms” are based on the behavior of the larvae of this group, which can occur in destructive swarms and cut the stems of plants.[9]

Ecology

Distribution and diversity

.jpg)

This family is cosmopolitan and can be found worldwide except in the Antarctic region. However, some species such as the Setaceous hebrew character (Xestia c-nigrum) can be found in the Arctic Circle, specifically in the Yukon territory of western Canada, with an elevation 1,702 m above sea level, where the temperature fluctuates between 23/-25 °C (73/-13 °F).[10] Many species of dart moths have been recorded in elevations as high as 4,000 m above sea level (e.g. Xestia elisabetha).[11]

Among the places where the number of species has been counted are North America and Northern Mexico, with about 2,522 species. 1,576 species are found in Europe, while the other species are distributed worldwide.[12][13][14][15][3]

Mutualism

.jpg)

Members of Noctuidae, like other butterflies and moths, perform an important role in plant pollination. However, some species have developed a stronger connection with their host plants. For example, the Lychnis moth (Hadena bicruris) has a strange mutualistic relationship with pink plants or carnation plants (Caryophyllaceae), in that larvae feed on the plant, but at the same the adults pollinate the flowers.[16]

Food guilds

Herbivory: It well-known that caterpillars feed on plants, flowers and fruits. However, many noctuids have a particular interest for toxic plants because they are able to withstand the chemical defenses of plants, as in the case of the Splendid brocade (Lacanobia splendens) which is capable of feeding on Cowbane (Cicuta virosa), one of the most poisonous plant on the world.[17]

Predation and Cannibalism: During the larval stage, some cutworms prefer to feed on other insects. One of them is the Shivering Pinion (Lithophane querquera), which commonly feed on other Lepidoptera larvae.[18] Moreover, it is well-known that larvae of the Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) like to eat their siblings.[19]

Nectarivory and Puddling: Like many Lepidoptera, Noctuids feed on the nectar of flowers. They also have other food resources such as dung, urea and mud, among others.[20]

Like the other members of the order Lepidoptera, courtship consists of a set of movements, where the female evaluates the male's skills.[20]

Most noctuid moths have organs known as hairy pedicels and pheromone glands, which are important for releasing pheromones or chemical compounds to attract males or females. It is well known that pheromones in the female are to call males, but the compounds in males are still under study.[21][22][20]

Reproduction

.jpg)

Noctuid moths commonly begin the reproductive season from spring to fall, and mostly are multivoltine, such as the Eastern Panthea moth (Panthea furcilla), which reproduces over the year.[23] Nevertheless, some species have just one brood of offspring (univoltine); among the best known is the Lesser yellow underwing (Noctua comes).[23]

Defense

%2C_feeding_on_amaryllis.jpg)

This group has a wide range of both chemical and physical defenses. Among the chemical defenses three types stand out. First, the pyrrolizidine alkaloid sequestration usually present in Arctiinae is also found in a few species of noctuids, including the Spanish moth (Xanthopastis timais).[24] Another chemical defense is formic acid production, which was thought to be present only in Notodontidae, but later was found in caterpillars of Trachosea champa.[25] Finally, the last type of chemical defense is regurgitation of plant compounds, often used by many insects, but the Cabbage Palm Caterpillar (Litoprosopus futilis) produces a toxin called toluquinone that deters predators.[26]

On the other hand, the main physical defense in caterpillars and adults alike is mimicry. Most owlet moths have drab colors with a variety of patterns suitable to camouflage their bodies.[23] The second physical defense consists in thousands of secondary setae that surround the body. The subfamilies that present this mechanism are Pantheinae and Acronictinae. The third is aposematism, represented by species of Cucullinae.[23] Finally, all adults have another mechanism for defense: a tympanal organ available to hear the echolocation spread out by bats, so the moths can avoid them.[27]

Human importance

.jpg)

Agriculture

Many species of owlet moths are considered an agricultural problem around the world. Their larvae are typically known as "cutworms" or "armyworms" due to enormous swarms that destroy crops, orchards and gardens every year. The old world bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) produces losses in agriculture every year that exceed US $2 billion.[28]

Systematics

Since molecular analysis began to play a larger role in systematics, the structure of many Lepidoptera groups has been changing and Noctuidae is not an exception. Most recent studies have shown that Noctuidae sensu stricto is a monophyletic group, mainly based on trifine venation. However there are some clades within Noctuidae sensu lato that have to be studied. This taxonomic division represent the subfamilies, tribes and subtribes considered so far.[1][12]

- Family Noctuidae Latreille, 1809

- Subfamily Plusiinae Boisduval, [1828]

- Tribe Abrostolini Eichlin & Cunningham, 1978

- Tribe Argyrogrammatini Eichlin & Cunningham, 1978

- Tribe Plusiini Boisduval, [1828]

- Subtribe Autoplusiina Kitching, 1987

- Subtribe Euchalciina Chou & Lu, 1979

- Subtribe Plusiina Boisduval, [1828]

- Subfamily Bagisarinae Crumb, 1956

- Tribe Cydosiini Kitching & Rawlins, [1998]

- Subfamily Eustrotiinae Grote, 1882

- Subfamily Acontiinae Guenée, 1841

- Tribe Acontiini Guenée, 1841

- Subfamily Pantheinae Smith, 1898

- Subfamily Dilobinae Aurivillius, 1889

- Subfamily Balsinae Grote, 1896

- Subfamily Acronictinae Heinemann, 1859

- Subfamily Metoponiinae Herrich-Schäff er, [1851]

- Subfamily Cuculliinae Herrich-Schäff er, [1850]

- Subfamily Amphipyrinae Guenée, 1837

- Tribe Amphipyrini Guenée, 1837

- Tribe Psaphidini Grote, 1896

- Subtribe Psaphidina Grote, 1896

- Subtribe Feraliina Poole, 1995

- Subtribe Nocloina Poole, 1995

- Subtribe Triocnemidina Poole, 1995

- Tribe Stiriini Grote, 1882 293

- Subfamily Oncocnemidinae Forbes & Franclemont, 1954

- Subfamily Agaristinae Herrich-Schäff er, [1858]

- Subfamily Condicinae Poole, 1995

- Tribe Condicini Poole, 1995

- Tribe Leuconyctini Poole, 1995

- Subfamily Heliothinae Boisduval, [1828]

- Subfamily Eriopinae Herrich-Schäff er, [1851]

- Subfamily Bryophilinae Guenée, 1852

- Subfamily Noctuinae Latreille, 1809

- Tribe Pseudeustrotiini Beck, 1996

- Tribe Phosphilini Poole, 1995

- Tribe Prodeniini Forbes, 1954

- Tribe Elaphriini Beck, 1996

- Tribe Caradrinini Boisduval, 1840

- Subtribe Caradrinina Boisduval, 1840

- Subtribe Athetiina Fibiger & Lafontaine, 2005

- Tribe Dypterygiini Forbes, 1954

- Tribe Actinotiini Beck, 1996

- Tribe Phlogophorini Hampson, 1918

- Tribe Apameini Guenée, 1841

- Tribe Arzamini Grote, 1883

- Tribe Xylenini Guenée, 1837

- Tribe Orthosiini Guenée, 1837

- Tribe Tholerini Beck, 1996

- Tribe Hadenini Guenée, 1837

- Tribe Leucaniini Guenée, 1837

- Tribe Eriopygini Fibiger & Lafontaine, 2005

- Tribe Glottulini Guenée, 1852

- Tribe Noctuini Latreille, 1809

- Subtribe Agrotina Rambur, 1848

- Subtribe Noctuina Latreille, 1809

- Subfamily Raphiinae Beck, 1996

- Subfamily Eucocytiinae Hampson, 1918.

- Subfamily Plusiinae Boisduval, [1828]

References

- 1 2 Regier, Jerome C.; Mitter, Charles; Mitter, Kim; Cummings, Michael P.; Bazinet, Adam L.; Hallwachs, Winifred; Janzen, Daniel H.; Zwick, Andreas (2017-01-01). "Further progress on the phylogeny of Noctuoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) using an expanded gene sample". Systematic Entomology. 42 (1): 82–93. ISSN 1365-3113. doi:10.1111/syen.12199.

- ↑ Lafontaine, J. Donald; Fibiger, Michael (2006-10-01). "Revised higher classification of the Noctuoidea (Lepidoptera)". The Canadian Entomologist. 138 (5): 610–635. ISSN 1918-3240. doi:10.4039/n06-012.

- 1 2 Michael, Fibiger,; Donald, Lafontaine, J.; H., Hacker, Hermann (2005-01-01). A review of the higher classification of the Noctuoidea (Lepidoptera) with special reference to the Holarctic fauna. Beilage zu Band 11 : (Notodontidae, Nolidae, Arctiidae, Lymantriidae, Erebidae, Micronoctuidae, and Noctuidae) : Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis Bände 1-10 : Indices Bände 1-10. Delta-Druck und Verlag Peks. ISBN 3938249013. OCLC 928877801.

- ↑ Zahiri, Reza; Holloway, Jeremy D.; Kitching, Ian J.; Lafontaine, J. Donald; Mutanen, Marko; Wahlberg, Niklas (2012-01-01). "Molecular phylogenetics of Erebidae (Lepidoptera, Noctuoidea)". Systematic Entomology. 37 (1): 102–124. ISSN 1365-3113. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2011.00607.x.

- ↑ Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Magnolia Press. 2011-01-01. ISBN 9781869778491.

- ↑ Fibiger, Michael (2007-01-01). The Lepidoptera of Israel. Coronet Books Incorporated. ISBN 9789546422880.

- ↑ Wagner, David L. (2010-04-25). Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400834147.

- ↑ Speidel, W.; Naumann, C. M. (2004-11-01). "A survey of family‐group names in noctuoid moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera)". Systematics and Biodiversity. 2 (2): 191–221. ISSN 1477-2000. doi:10.1017/S1477200004001409.

- ↑ E., Rice, Marlin (2004-01-01). "Armyworm defoliating young corn".

- ↑ Lafontaine, J. D; Wood, D. M. "Butterflies and moths of the Yukon" (PDF). http://hocking.biology.ualberta.ca. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Gyulai, P.; Ronkay, L.; Saldaitis, A. (2013-11-04). "Two new Xestia Hübner, 1818 species from China (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae)". Zootaxa. 3734 (1): 96–100. ISSN 1175-5334. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3734.1.12.

- 1 2 Schmidt, B. Christian; Lafontaine, J. Donald (2010-03-19). Annotated Check List of the Noctuoidea (Insecta, Lepidoptera) of North America North of Mexico. PenSoft Publishers LTD. ISBN 9789546425355.

- ↑ Schmidt, Bjorn Christian; Lafontaine, J. Donald (2011-11-24). Contributions to the Systematics of New World Macro-moths III. PenSoft Publishers LTD. ISBN 9789546426185.

- ↑ Lafontaine, Donald; Schmidt, Christian (2013-06-02). "Additions and corrections to the check list of the Noctuoidea (Insecta, Lepidoptera) of North America north of Mexico". ZooKeys. 264: 227–236. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 3668382

. PMID 23730184. doi:10.3897/zookeys.264.4443.

. PMID 23730184. doi:10.3897/zookeys.264.4443. - ↑ Lafontaine, J. Donald; Schmidt, B. Christian (2015-10-15). "Additions and corrections to the check list of the Noctuoidea (Insecta, Lepidoptera) of North America north of Mexico III". ZooKeys (527): 127–147. ISSN 1313-2989. PMC 4668890

. PMID 26692790. doi:10.3897/zookeys.527.6151.

. PMID 26692790. doi:10.3897/zookeys.527.6151. - ↑ Bopp, Sigrun; Gottsberger, Gerhard (2004-01-01). "Importance of Silene latifolia ssp. alba and S. dioica (Caryophyllaceae) as Host Plants of the Parasitic Pollinator Hadena bicruris (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae)". Oikos. 105 (2): 221–228.

- ↑ Jacobs, Maarten (2005). "Lacanobia splendens, a new species for the Belgian fauna (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)" (PDF). Phegea. 33 (3): 83–85.

- ↑ D.F., Schweitzer, (1979-01-01). "Predatory behavior in Lithophane querquera and other spring caterpillars". Journal. ISSN 0024-0966.

- ↑ Chapman, Jason W.; Williams, Trevor; Martínez, Ana M.; Cisneros, Juan; Caballero, Primitivo; Cave, Ronald D.; Goulson, Dave (2000-01-01). "Does Cannibalism in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Reduce the Risk of Predation?". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 48 (4): 321–327.

- 1 2 3 Birch, Martin (1970-05-01). "Pre-courtship use of abdominal brushes by the nocturnal moth, Phlogophora meticulosa (L.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)". Animal Behaviour. 18, Part 2: 310–316. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(70)80043-4.

- ↑ Heath, R. R.; Mclaughlin, J. R.; Proshold, F.; Teal, P. E. A. (1991-03-01). "Periodicity of Female Sex Pheromone Titer and Release in Heliothis subflexa and H. virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 84 (2): 182–189. ISSN 0013-8746. doi:10.1093/aesa/84.2.182.

- ↑ Ronkay, L. (2005). "Revision of the genus Lophoterges Hampson, 1906 (s. l.) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Cuculliinae). Part II. The genus Lophoterges s. str.". Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 51: 1–57.

- 1 2 3 4 Wagner, David L. (2011-01-01). Owlet Caterpillars of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150427.

- ↑ Vilanova, Cristina; Baixeras, Joaquín; Latorre, Amparo; Porcar, Manuel (2016-01-01). "The Generalist Inside the Specialist: Gut Bacterial Communities of Two Insect Species Feeding on Toxic Plants Are Dominated by Enterococcus sp.". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 4923067

. PMID 27446044. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01005.

. PMID 27446044. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01005. - ↑ Nakamura, M. (1998). "The eversible cervical gland and the chemical component of its secretion in noctuid larvae" (PDF). Transactions of the Lepidopterological Society of Japan. 49: 85–92.

- ↑ Smedley, Scott R.; Ehrhardt, Elizabeth; Eisner, Thomas. "Defensive Regurgitation by a Noctuid Moth Larva (Litoprosopus Futilis)". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 100 (3-4): 209–221. ISSN 0033-2615. doi:10.1155/1993/67950.

- ↑ Kristensen, Niels (2003-01-01). Vol 2: Morphology, Physiology, and Development. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110893724.

- ↑ Narayanamma, V. Lakshmi; Sharma, H. C.; Gowda, C. L. L.; Sriramulu, M. (2007-12-01). "Incorporation of lyophilized leaves and pods into artificial diets to assess the antibiosis component of resistance to pod borer Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in chickpea". International Journal of Tropical Insect Science. 27 (3-4): 191–198. ISSN 1742-7592. doi:10.1017/S1742758407878374.

External links

On the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site:

- Agrotis ipsilon, black cutworm

- Diphthera festiva, hieroglyphic moth

- Litoprosopus futilis , cabbage palm caterpillar

- Pseudaletia unipuncta, true armyworm

- Spodoptera eridania, southern armyworm

- Spodoptera frugiperda, fall armyworm

- Spodoptera ornithogalli, Yellowstriped Armyworm

- Xanthopastis timais, Spanish moth or convict caterpillar

- Family Noctuidae at Insecta.pro

- Images of Noctuidae species in New Zealand

- Moth Photographers Group-Mississippi State University