Psalm 127

Psalm 127 (Vulgate Psalm 126) is one of 15 "Songs of Ascents" in the Book of Psalms, the only one among these attributed to Solomon (rather than David). In Jewish liturgy it is recited following Mincha between Sukkot and Shabbat Hagadol.[1]

The text is divided in five verses. The first two express the notion that "without God, all is in vain", popularly summarized in Latin in the motto Nisi Dominus Frustra. The remaining three verses describe progeny as God's blessing. The Vulgate text, known from its incipit as Nisi Dominus, was set to music numerous times during the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Translation

The translation of the psalm offers difficulties, especially in verses 2 and 4.

Jerome in a letter to Marcella (dated AD 384) laments that Origen's notes on this psalm were no longer extant, and discusses the various possible translations of לֶחֶם הָעֲצָבִים (KJV "bread of sorrows", after the panem doloris of Vulgata Clementina; Jerome's own translation was panem idolorum "bread of idols" following LXX), and of בְּנֵי הַנְּעוּרִֽים׃ (KJV "children of the youth", mistranslated in LXX as υἱοὶ τῶν ἐκτετιναγμένων "children of the outcast").[2]

There are two possible interpretations of the phrase כֵּן יִתֵּן לִֽידִידֹו שֵׁנָֽא (KJV "for so he giveth his beloved sleep"): The word "sleep" may either be the direct object (as in KJV, following LXX and Vulgate), or an accusative used adverbially, "in sleep", i.e. "while they are asleep". The latter interpretation fits the context of the verse much better, contrasting the "beloved of the Lord" who receive success without effort, as it were "while they sleep" with the sorrowful and fruitless toil of those not so blessed, a sentiment paralleled by Proverbs 10:22 (KJV "The blessing of the LORD, it maketh rich, and he addeth no sorrow with it."). Keil and Delitzsch (1883) accept the reading of the accusative as adverbial, paraphrasing ""God gives to His beloved in sleep, i.e., without restless self-activity, in a state of self-forgetful renunciation, and modest, calm surrender to Him".[3] However, A. F. Kirkpatrick in the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1906) argues that while the reading "So he giveth unto his beloved in sleep" fits the context, the natural translation of the Hebrew text is still the one given by the ancient translators, suggesting that the Hebrew text as transmitted has been corrupted (which would make the LXX and Vulgate readings not so much "mistranslations" as correct translations of an already corrupted reading).[4] English translations have been reluctant to emend the translation, due to the long-standing association of this verse with sleep being the gift of God.[5] Abraham Cronbach (1933) refers to this as "one of those glorious mistranslations, a mistranslation which enabled Mrs. Browning to write one of the tenderest poems in the English language",[6] referring to Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poem The Sleep, which uses "He giveth his beloved Sleep" as the last line of each stanza.

Keil and Delitzsch (1883) take שֶׁבֶת "to sit up" as confirmation for the assumption, also suggested by 1 Samuel 20:24, that the custom of the Hebrews before the Hellenistic period was to take their meals sitting up, and not reclining as was the Greco-Roman custom.[7]

Uses

Judaism

In Judaism, Psalm 127 is recited in the Minchah of Shabbat, between Sukkot and Shabbat Hagadol.

Catholicism

Since the early Middle ages, that psalm was traditionally recited or sung at the Office of none during the week, specifically from Tuesday until Saturday between Psalm 126 and Psalm 128, of after the rule of St. Benedict.[8]

During the Liturgy of the Hours, Psalm 126 is recited on the third Wednesday at vespers.[9]

Musical settings

The Vulgate text of the psalm has been set to music numerous times, under the title Nisi Dominus ("Unless the Lord") after its incipit. Classical musical settings use the text of the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate of 1592, which groups Cum dederit dilectis suis somnum ("as he gives sleep to those in whom he delights") with verse 3 rather than verse 2 (as opposed to Jerome's text, and most modern translations, grouping the phrase with verse 2). Notable compositions include:[10]

- Orlando di Lasso, a capella motet for five voices, published in 1562.[11]

- Hans Leo Hassler, a capella motet, published in Cantiones sacrae, 1591

- Giovanni Matteo Asola has an a capella setting published in 1599.

- Monteverdi's Nisi Dominus for ten-voice choir is part of the Vespers of 1610 (SV 206).

- Alessandro Grandi, motet with trombones and basso continuo, published 1630.

- Francesco Cavalli, setting for four voices and strings, published in Musiche Sacre Concernenti, Venice, 1656.

- Giovanni Giacomo Arrigoni has a setting as a motet, published in 1663.

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier H.160, motet with basso continuo, manuscript of c. 1670/2.

- Biber, cantata for 2 voices, violin and b.c. (after 1676).

- Handel's Nisi Dominus is believed to have been written for a vespers service, in 1707.

- Jan Dismas Zelenka wrote a Nisi Dominus (ZWV 92) in c. 1726.

- Vivaldi produced two settings, RV 608 for strings and solo voice and RV 803 for strings and choir, discovered among the "Galuppi" sacred works in the Saxon State and University Library Dresden in 2006.[12]

Wo Gott zum Haus is a German metrical and rhyming paraphrase of the psalm by Johann Kolross, set to music by Luther (printed 1597) and by Hans Leo Hassler (c. 1607). Adam Gumpelzhaimer used the first two lines for a canon, Wo Gott zum Haus nicht gibt sein Gunst / So arbeit jedermann umsonst ("Where God to the house does not give his blessing / There toils every man in vain"). Another German version is Wo der Herr nicht das Haus bauet by Heinrich Schütz (SWV 400, published 1650).

Nisi Dominus Frustra

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nisi dominus frustra. |

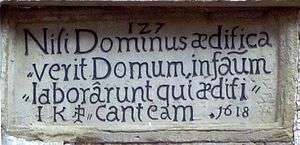

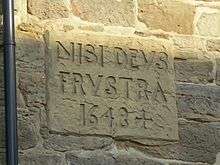

Nisi Dominus Frustra - "if not the Lord — in vain" (viz. "without the Lord, all is in vain") is a popular motto derived from verse 1. As an abbreviation of "Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it", it is often inscribed on buildings, and it is the motto in the coat of arms of Edinburgh and was the motto of the former Metropolitan Borough of Chelsea.

The Aquitanian city of Agen takes as its motto the second sentence of the psalm, Nisi dominus custodierit civitatem frustra vigilat qui custodit eam: Unless the Lord watches over the city, the guards stand watch in vain (verse 1a, NIV version).

Edinburgh Napier University, established in 1964, has "secularized" the city's motto to Nisi sapientia frustra (i.e. "without knowledge/wisdom, all is in vain").

Nisi Dominus Frustra is also the motto of numerous schools including Villa Maria Academy (Malvern, Pennsylvania), Rickmansworth School (Nisi Dominus Aedificaverit), The Park School, Yeovil, Bukit Bintang Girls' School, St Thomas School, Kolkata and Mount Temple Comprehensive School, Dublin, Ireland.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psalm 127. |

- ↑ Nosson Scherman (ed.), The Complete Artscroll Siddur (1984), p. 530.

- ↑ Ph. Schaff, H. Wace, The Principal Works of St. Jerome (1892), Letter xxxiv. To Marcella "The Hebrew phrase 'bread of sorrow' is rendered by the LXX. 'bread of idols'; by Aquila, 'bread of troubles'; by Symmachus, 'bread of misery.' Theodotion follows the LXX. So does Origen's Fifth Version. The Sixth renders 'bread of error.' In support of the LXX. the word used here is in Ps. cxv.4, translated 'idols.' Either the troubles of life are meant or else the tenets of heresy."

- ↑ "God gives to His beloved (Psalm 60:7; Deuteronomy 33:12) שׁנא (equals שׁנה), in sleep (an adverbial accusative like לילה בּּקר, ערב), i.e., without restless self-activity, in a state of self-forgetful renunciation, and modest, calm surrender to Him: "God bestows His gifts during the night," says a German proverb, and a Greek proverb even says: εὕδοντι κύρτος αἱρεῖ [the fish-trap catches while they sleep]. Bücher takes כּן in the sense of "so equals without anything further;" and כן certainly has this meaning sometimes (vid., introduction to Psalm 110:1-7), but not in this passage, where, as referring back, it stands at the head of the clause, and where what this mimic כן would import lies in the word שׁנא." Carl Friedrich Keil, Franz Delitzsch Commentary on the Old Testament (Biblischer Kommentar über das Alte Testament vol. 8, 1883), English edition by T. and T. Clark, Edinburgh (1892–94).

- ↑ "Most commentators however adopt the rendering, So he giveth unto his beloved in sleep. This rendering is certainly not the natural rendering of the Heb. text. Wellhausen condemns it as “quite inadmissible.” It requires the supplement of an object to the verb, and שֵׁנָא must be taken as accus. of manner. If it were not for the exegetical difficulty, no one would hesitate to take ‘sleep,’ as the Ancient Versions take it, as the object of the verb ‘giveth.’ Some word however seems to be needed to correspond to the results of anxious toil, and though the Ancient Versions already had the present reading, the text may be corrupt. The anomalous form of the word for sleep (שנא for שנה) may point in this direction."

- ↑ Charles Ellicott, Commentary for English Readers (1897). Modern translations which do emend the passage include: Brenton (1844), New American Standard Bible (1968), Complete Jewish Bible (1998), New English Translation (2005); Luther (1545) already has "denn seinen Freunden gibt er's schlafend." ("as to his friends he grants while [they are] asleep."

- ↑ Abraham Cronbach, Religion and Its Social Setting: Together with Other Essays (1933), p. 193.

- ↑ Carl Friedrich Keil, Franz Delitzsch Commentary on the Old Testament ( Biblischer Kommentar über das Alte Testament vol. 8, 1883), English edition by T. and T. Clark, Edinburgh (1892–94).

- ↑ Prosper Guéranger, Règle de saint Benoît, (Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes, réimpression 2007) p46.

- ↑ Le cycle principal des prières liturgiques se déroule sur quatre semaines.

- ↑ see Psalm 127 at Choral Public Domain Library for a detailed list.

- ↑ Sacrae cantiones quinque vocum, Nuremberg, 1562), no. 15. Lasso's version predates the Vulgata Clementina, but his text already follows its reading Cum dederit dilectis suis somnum, ecce hæreditas Domini filii, merces fructus ventris. which is derived from revised editions of the Vulgate published in the first half of the 16th century, notably those by Stephanus.

- ↑ J.B. Stockigt, M. Talbot, "Two More New Vivaldi Finds in Dresden", Eighteenth Century Music 3.1 (March 2006), 35–61.