Nimodipine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nimotop |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a689010 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 13% (Oral) |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 8–9 hours |

| Excretion | Feces and Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.060.096 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H26N2O7 |

| Molar mass | 418.44 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 7 °C (45 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Nimodipine (marketed by Bayer as Nimotop) is a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker originally developed for the treatment of high blood pressure. It is not frequently used for this indication, but has shown good results in preventing a major complication of subarachnoid hemorrhage (a form of cerebral hemorrhage) termed vasospasm; this is now the main use of nimodipine.

Dosage

The regular dosage is 60 mg tablets every four hours. If the patient is unable to take tablets orally, it was previously given via intravenous infusion at a rate of 1–2 mg/hour (lower dosage if the body weight is <70 kg or blood pressure is too low),[1] but since the withdrawal of the IV preparation, administration by nasogastric tube is an alternative.

Usage

Because it has some selectivity for cerebral vasculature, nimodipine's main use is in the prevention of cerebral vasospasm and resultant ischemia, a complication of subarachnoid hemorrhage (a form of cerebral bleed), specifically from ruptured intracranial berry aneurysms irrespective of the patient's post-ictus neurological condition.[2] Its administration begins within 4 days of a subarachnoid hemorrhage and is continued for three weeks. If blood pressure drops by over 5%, dosage is adjusted. There is still controversy regarding the use of intravenous nimodipine on a routine basis.[1][3]

A 2003 trial (Belfort et al.) found nimodipine was inferior to magnesium sulfate in preventing seizures in women with severe preeclampsia.[4]

Nimodipine is not regularly used to treat head injury. Several investigations have been performed evaluating its use for traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage; a systematic review of 4 trials did not suggest any significant benefit to the patients that receive nimodipine therapy.[5] There was one report case of nimodipine being successfully used for treatment of ultradian bipolar cycling after brain injury and, later, amygdalohippocampectomy.[6]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

After oral administration, it reaches peak plasma concentrations within one and a half hours. Patients taking enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants have lower plasma concentrations, while patients taking sodium valproate were markedly higher.[7]

Metabolism

Nimodipine is metabolized in the first pass metabolism. The dihydropyridine ring of the nimodipine is dehydrogenated in the hepatic cells of the liver, a process governed by cytochrome P450 isoform 3A (CYP3A). This can be completely inhibited however, by troleandomycin (an antibiotic) or ketoconazole (an antifungal drug).[8]

Excretion

Studies in non-human mammals using radioactive labeling have found that 40–50% of the dose is excreted via urine. The residue level in the body was never more than 1.5% in monkeys.

Mode of action

Nimodipine binds specifically to L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. There are numerous theories about its mechanism in preventing vasospasm, but none are conclusive.[9]

Nimodipine has additionally been found to act as an antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor, or as an antimineralocorticoid.[10]

Contraindications

Nimodipine is associated with low blood pressure, flushing and sweating, edema, nausea and other gastrointestinal problems, most of which are known characteristics of calcium channel blockers. It is contraindicated in unstable angina or an episode of myocardial infarction more recently than one month.

While nimodipine was occasionally administered intravenously in the past, the FDA released an alert in January 2006 warning that it had received reports of the approved oral preparation being used intravenously, leading to severe complications; this was despite warnings on the box that this should not be done.[11]

Side-effects

The FDA has classified the side effects into groups based on dosages levels at q4h. For the high dosage group (90 mg) less than 1% of the group experienced adverse conditions including itching, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, neurological deterioration, vomiting, diaphoresis, congestive heart failure, hyponatremia, decreasing platelet count, disseminated intravascular coagulation, deep vein thrombosis.[2]

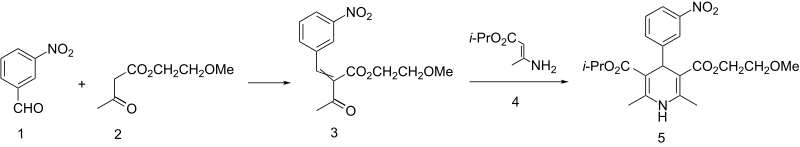

Synthesis

The key acetoacetate (2) for the synthesis of nimodipine (5) is obtained by alkylation of sodium acetoacetate with 2-methoxyethyl chloride, Aldol condensation of meta-nitrobenzene (1) and the subsequent reaction of the intermediate with enamine (4) gives nimodipine.

Notes

- Pharmacology: R. Towart, S. Kazda, Br. J. Pharmacol. 67, 409P (1979).

- Use as cerebral vasodilator: H. Meyer et al., GB 2018134; eidem, U.S. Patent 4,406,906 (1979, 1983 to Bayer).

- Effect on associative learning in aging rabbits: R. A. Deyo et al., Science 243, 809 (1989).

References

- 1 2 Janjua N, Mayer SA; Mayer (2003). "Cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage". Current Opinion in Critical Care. 9 (2): 113–9. PMID 12657973. doi:10.1097/00075198-200304000-00006.

- 1 2 "FDA approved Labeling text. Nimotop (nimodipine) Capsules For Oral Use" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. December 2005. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ↑ Allen GS, Ahn HS, Preziosi TJ, et al. (1983). "Cerebral arterial spasm--a controlled trial of nimodipine in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage". New England Journal of Medicine. 308 (11): 619–24. PMID 6338383. doi:10.1056/NEJM198303173081103.

- ↑ Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, Allen JC; Anthony; Saade; Allen Jr; Nimodipine Study (2003). "A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia". New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (4): 304–11. PMID 12540643. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021180.

- ↑ Vergouwen MD, Vermeulen M, Roos YB; Vermeulen; Roos (2006). "Effect of nimodipine on outcome in patients with traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review". Lancet Neurology. 5 (12): 1029–32. PMID 17110283. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70582-8.

- ↑ De León OA. (2012). "Response to nimodipine in ultradian bipolar cycling after amygdalohippocampectomy.". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 32 (1): 146–148. PMID 22217956. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31823f9116.

- ↑ Tartara, A; Galimberti, C. A.; Manni, R; Parietti, L; Zucca, C; Baasch, H; Caresia, L; Mück, W; Barzaghi, N; Gatti, G; Perucca, E (1991). "Differential effects of valproic acid and enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants on nimodipine pharmacokinetics in epileptic patients". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 32 (3): 335–340. PMC 1368527

. PMID 1777370. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03908.x.

. PMID 1777370. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03908.x. - ↑ http://www.chinaphar.com/1671-4083/21/690.pdf

- ↑ Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-07145-4.

- ↑ Luther, James M. (2014). "Is there a new dawn for selective mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism?". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 23 (5): 456–461. ISSN 1062-4821. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000051.

- ↑ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Nimodipine (marketed as Nimotop)". Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

External links

- Nimotop (manufacturer's website)