Nils Gustaf Nordenskiöld

| Nils Nordenskiöld | |

|---|---|

|

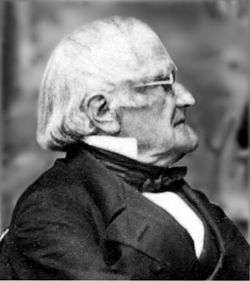

N. Nordenskiöld (Photo publ., 1870) | |

| Born |

12 October 1792 Mäntsälä, Finland |

| Died |

2 February 1866 (aged 74) Helsingfors, Finland |

| Nationality | Russian Empire |

| Fields | Mineralogy |

| Known for | New minerals |

| Influenced | A. E. Nordenskiöld |

|

Signature | |

Nils Gustaf Nordenskiöld (October 12, 1792, Mäntsälä – February 2, 1866) was a mineralogist and a traveller. He was the father of mineralogist and polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld.

Life

Nordenskiöld was born in Mäntsälä in southern Finland, which was then part of the Kingdom of Sweden. After studying mineralogy in Helsingfors, now better known as Helsinki, and in Sweden, Nordenskiöld was appointed an inspector of mines in Finland. Finland had by now been transferred to Russia, as an autonomous Grand Duchy.

On October 3, 1819, Nordenskiöld was elected a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The Academy had been established pursuant to the order of the Peter I of Russia by the Decree of the Ruling Senate dated January 28 (February 8), 1724. In 1853, he was also elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Nordenskiöld described and discovered a number of minerals previously unknown in Finland and Russia. In 1820, Nordenskiöld published a treatise, which was renowned as the first scientific handbook on Finnish minerals. He also published a number of articles in foreign journals, which brought him to notice far beyond Scandinavia. In future years, he was to ensure that his son, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, shared this knowledge and became renowned as an explorer in his own right.[1]

Nordenskiöld returned to Finland in 1823 and in 1828 was appointed superintendent of the newly established Mining Board in Helsingfors, a post he held until his death in 1865.

Gemstone discoveries

According to a widely popular but controversial story, alexandrite was discovered by Nordenskiöld, on the tsarevitch Alexander's sixteenth birthday on April 17, 1834 and named Alexandrite in honor of the future Tsar — Alexander II of Russia.[2] Although it was Nordenskiöld who discovered alexandrite, he could not possibly have discovered and named it on Alexander's birthday. Nordenskiöld's initial discovery occurred as a result an examination of a newly found mineral sample he had received from Count Lev Alekseevich Perovskii (1792–1856), which he identified it as emerald at first. Confused with the high hardness, he decided to continue his examinations. Later that evening, while looking at the specimen under candlelight, he was surprised to see that the color of the stone had changed to raspberry-red instead of green. Later, he confirmed the discovery of a new variety of chrysoberyl, and suggested the name "diaphanite"(from the Greek "di" two and "aphanes", unseen or "phan", to appear, or show). Perovskii however had his own plans and used the rare specimen to ingratiate himself with the Imperial family by presenting it to the future Tsar and naming it Alexandrite in his honor on April 17, 1834, but it wasn't until 1842 that the description of the color changing chrysoberyl was published for the first time under the name of alexandrite.[3]

Other minerals

Other minerals described by Nordenskiöld include :

- anorthite, under the name of amphodelite[4]

- ainalite in 1855, a variety of cassiterite[5]

- samarskite-(Y), under the name of adelpholite in 1855[5]

- crookesite in 1866[6]

- kämmererite in 1841, a variety of clinochlore

- lazur-apatite in 1857, a variety of apatite[7]

- anorthite, under the name of lepolite[8]

In 1849, Nordenskjold examined what was known as "Ural's chrysolite" and discovered that it was a rich green variety of andradite garnet. In 1854, he proposed for it the name demantoid ("like a diamond").

See also

References

- ↑ Alexandrite chronological backstory. (2006, December 7). In Alexandrite.net, Tsarstone collectors guide. Retrieved online 12:46, February 26, 2007

- ↑ Nordenskiöld N. Alexandrit oder Ural Chrysoberyll // Schriften der St.-Petersburg geschrifteten Russisch-Kaiserlichen Gesellschaft fuer die gesammte Mineralogie. 1842. Bd 1. S. 116-127.

- ↑ Chapter 2: Diaphanite or Alexandrite? (2006, December 7). In Alexandrite.net, Tsarstone collectors guide. Retrieved online 12:40, February 26, 2007

- ↑ Armand Dufrénoy, Traité de minéralogie, vol. 3, 1856. p. 665

- 1 2 "Beskrifnung oefver de i Finland funna Min.", Helsinfors(162) p.1855

- ↑ Ak.Stockholm, Ofversigt. (23) p.365

- ↑ Nordenskiöld (1857) (Moscow Society of Naturalists): 30: 217, 224

- ↑ Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles, vol. 11-13, p. 315, 1849

External links

- Letter exchange between Nordenskiöld and Berzelius on Wikisource (Swedish with presentation and abstracts in French)

- Alexandrite Tsarstone Collectors Guide

- The Russian Academy of Sciences

- Records of University of Helsinki