Syrtis Major Planum

|

Mars digital-image mosaic merged with color of the MC-13 quadrangle, Syrtis Major region of Mars. | |

| Coordinates | 8°24′N 69°30′E / 8.4°N 69.5°ECoordinates: 8°24′N 69°30′E / 8.4°N 69.5°E |

|---|---|

Syrtis Major Planum is a "dark spot" (an albedo feature) located in the boundary between the northern lowlands and southern highlands of Mars just west of the impact basin Isidis in the Syrtis Major quadrangle. It was discovered, on the basis of data from Mars Global Surveyor, to be a low-relief shield volcano,[1] but was formerly believed to be a plain, and was then known as Syrtis Major Planitia. The dark color comes from the basaltic volcanic rock of the region and the relative lack of dust.

A possible landing site for the Mars 2020 rover mission[2] is Jezero crater (at 18°51′18″N 77°31′08″E / 18.855°N 77.519°E)[3] within the region. The northeastern region of Syrtis Major Planum is also considered a potential landing site.

Geography and geology

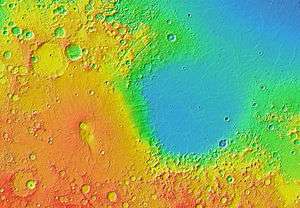

Syrtis Major is centered near at 8°24′N 69°30′E / 8.4°N 69.5°E, extends some 1,500 km (930 mi) north from the planet's equator, and spans 1,000 km (620 mi) from west to east. It is in the Syrtis Major quadrangle. It encompasses a large slope from its western edge at Aeria dropping 4 km (2.5 mi) to its eastern edge at Isidis Planitia. It includes a high-altitude bulge that rises 6 km (3.7 mi) at 310° W. Most of Syrtis Major has slopes of less than 1°, a much lower inclination than the slopes of the Tharsis shield volcanoes. It has a 350 by 150 km north-south elongated central depression containing the calderas Nili Patera and Meroe Patera, which are about 2 km deep. The floors of the calderas are not elevated relative to the terrain surrounding Syrtis Major. The floor of Nili Patera is the less cratered, and therefore the younger, of the two. While most of the rock is basaltic, dacite has also been detected in Nili Patera.[4] Satellite gravity field measurements show a positive gravity anomaly centered on the caldera complex, suggesting the presence of a 600x300 km north-south elongated extinct magma chamber below, containing dense minerals (probably mainly pyroxene, with olivine also possible) that precipitated out of magma before eruptions.[5] Crater counts date Syrtis Major to the early Hesperian epoch; it postdates formation of the adjacent Isidis impact basin.[1]

Discovery and name

The name Syrtis Major is derived from the classical Roman name Syrtis maior for the Gulf of Sidra on the coast of Libya (classical Cyrenaica).

Syrtis Major was the first documented surface feature of another planet. It was discovered by Christiaan Huygens, who included it in a drawing of Mars in 1659. He used repeated observations of the feature to estimate the length of day on Mars.[6] The feature was originally known as the Hourglass Sea but has been given different names by different cartographers. In 1840, Johann Heinrich von Mädler compiled a map of Mars from his observations and called the feature Atlantic Canale. In Richard Proctor's 1867 map it is called then Kaiser Sea (after Frederik Kaiser of the Leiden Observatory). Camille Flammarion called it the Mer du Sablier (French for "Hourglass Sea") when he revised Proctor's nomenclature in 1876. The name "Syrtis Major" was chosen by Giovanni Schiaparelli when he created a map based on observations made during Mars' close approach to Earth in 1877.[7][8]

Seasonal variations

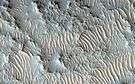

Syrtis Major was the object of much observation due to its seasonal and long-term variations. This led to theories that it was a shallow sea and later that its variability was due to seasonal vegetation. However, in the 1960s and 1970s, the Mariner and Viking planetary probes led scientists to conclude that the variations were caused by wind blowing dust and sand across the area. It has many windblown deposits that include light-colored halos or plumose streaks that form downwind of craters. These streaks are accumulations of dust resulting from disruption of the wind by the elevated rims of the craters ('wind shadows').[4]

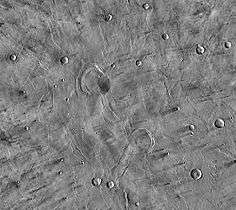

Moving sand dunes and ripples

Nili Paltera was the subject of a 2010 study into moving sand dunes and wind ripples. The study showed that dunes are active and that sand ripples are actively migrating on the surface of Mars.[9] A following study also showed that the sand dunes move at about the same flux (volume per time) as dunes in Antarctica. This was unexpected because of the thin air and the winds which are weaker than Earth winds. It may be due to "saltation" - ballistic movement of sand grains which travel further in the weaker Mars gravity.

The lee fronts of the dunes in this region move on average 0.5 meters per year (though the selection may be biased here as they only measured dunes with clear lee edges to measure) and the ripples move on average 0.1 meters per year.[10]

Gallery

MOLA map showing boundaries of Syrtis Major Planum and other regions. Colors indicate elevations.

MOLA map showing boundaries of Syrtis Major Planum and other regions. Colors indicate elevations.- Bright Streaks in Syrtis Major caused by the wind, as seen by THEMIS.

| Proposed Mars 2020 mission landing site - Jezero crater[2] (18°51′18″N 77°31′08″E / 18.855°N 77.519°E)[3] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

See also

References

- 1 2 Hiesinger, H.; Head (publications), J. W. (8 January 2004). "The Syrtis Major volcanic province, Mars: Synthesis from Mars Global Surveyor data" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 109 (E1): E01004. Bibcode:2004JGRE..10901004H. doi:10.1029/2003JE002143. E01004.

- 1 2 Staff (4 March 2015). "PIA19303: A Possible Landing Site for the 2020 Mission: Jezero Crater". NASA. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- 1 2 Wray, James (6 June 2008). "Channel into Jezero Crater Delta". NASA. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- 1 2 "Mars Odyssey Mission THEMIS web site". 23 October 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- ↑ Kiefer, Walter S. (30 May 2004). "Gravity evidence for an extinct magma chamber beneath Syrtis Major, Mars: a look at the magmatic plumbing system". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 222 (2): 349– 361. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.222..349K. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.03.009.

- ↑ "Mars Express reveals wind-blown deposits on Mars". European Space Agency. 3 February 2012.

- ↑ Morton, Oliver (2002). Mapping Mars: Science, Imagination, and the Birth of a World. New York: Picador USA. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-312-24551-3.

- ↑ William Sheehan. "The Planet Mars: A History of Observation and Discovery - Chapter 4: Areographers". Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ Silvestro, S.; Fenton, LK.; Vaz, DA.; Bridges, N.; Ori, GG. (27 October 2010). "Ripple migration and dune activity on Mars: Evidence for dynamic wind processes". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (20). Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3720203S. doi:10.1029/2010GL044743. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Bridges, N. T.; Ayoub, F.; Avouac, J-P.; Leprince, S.; Lucas, A.; Mattson, S. (2012). "Earth-like sand fluxes on Mars" (PDF). Nature. 485 (7398): 339–342. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..339B. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 22596156. doi:10.1038/nature11022.