Nikumaroro

Geographical map of Nikumaroro | |

|

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 4°40′48″S 174°31′01″W / 4.68°S 174.517°WCoordinates: 4°40′48″S 174°31′01″W / 4.68°S 174.517°W |

| Archipelago | Phoenix Islands |

| Length | 6 km (3.7 mi) |

| Width | 2 km (1.2 mi) |

| Administration | |

| Phoenix Islands Protected Area | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

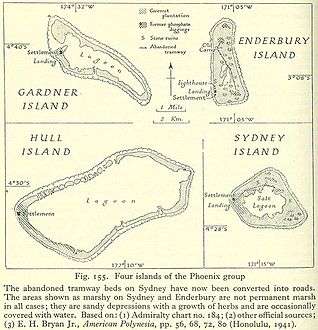

Nikumaroro, or Gardner Island, is part of the Phoenix Islands, Kiribati, in the western Pacific Ocean. It is a remote, elongated, triangular coral atoll with profuse vegetation and a large central marine lagoon. Nikumaroro is approximately 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi) long by 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) wide. There are two narrow entrances through the rim, both of which are blocked by a wide reef which is dry at low tide. The ocean beyond the reef is very deep and the only anchorage is at the island's west end, across the reef from the ruins of a mid-twentieth-century British colonial village, but this is safe only with the southeast trade winds. Landing has always been difficult and is most often done south of the anchorage. Although occupied at various times during the past, the island is uninhabited today.[1]

Kiribati declared the Phoenix Islands Protected Area in 2006, with the park being expanded in 2008. The 425,300-square-kilometer (164,200-square-mile) marine reserve contains eight coral atolls including Nikumaroro.[2][3]

Nikumaroro has been the focus of considerable speculation and exploration as a location where pilot Amelia Earhart might have crashed in July 1937 during her ill-fated final flight, attempting to circumnavigate the globe.[4][5]

Geography

Thick scrub and Pisonia forest cover the land surface. The trees grow 15 meters (49 ft) in height and result in decomposing leaf material in the soil.[1] Coconut palms remain from the attempts to operate a plantation on the island from 1893 to 1894 and 1938 to 1963.[1]

The scarcity of fresh water on Nikumaroro has proven problematic for residents in the past, and contributed directly to the failure of a British project to colonize the island from 1938 to 1963.

Flora and fauna

Nikumaroro is sporadically visited by biologists attracted to its extensive marine and avian ecosystems. The atoll has a large population of coconut crabs. Migratory birds and rats abound. Several species of shark and bottlenose dolphins have been observed in the surrounding waters.[6][7]

The island is part of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, and as such, has been named an Important Bird Area.[8]

History

19th century sightings and claims

Nikumaroro was known by sundry names during the early 19th century: Kemins' Island, Kemis Island, Motu Oonga, Motu Oona and Mary Letitia's Island. The first record of a European sighting was made by Capt. C. Kemiss (or Kemin, Kemish) from the British whaling ship Eliza Ann in 1824. On 19 August 1840, the USS Vincennes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition confirmed its position and recorded the atoll's name as Gardner Island, originally given in 1825 by Joshua Coffin of the Nantucket whaler Ganges. Some sources say the island was named after U.S. Congressman Gideon Gardner, who owned the Ganges.[1][9][N 1]

In 1856, Nikumaroro was claimed as "Kemins Island" by CA Williams & Co. of New London, Connecticut, under the American Guano Islands Act. There is no record of guano deposits ever being exploited, however.[9] On 28 May 1892, the island was claimed by the United Kingdom during a call by HMS Curacoa.[1] Almost immediately a license was granted to Pacific entrepreneur John T. Arundel for planting coconuts.[1] Twenty-nine islanders were settled there and some structures with corrugated iron roofs constructed, but a severe drought resulted in the failure of this project within a year. In 1916 it was leased to a Captain E.F.H. Allen of the Samoa Shipping Trading Co Ltd, but remained uninhabited until 1938.[1]

SS Norwich City wreck

During a storm on 29 November 1929, the SS Norwich City, a large unladen British freighter with a crew of 35 men, ran aground on the reef at the island's northwest corner. A fire broke out in the engine room and all hands abandoned ship in darkness through storm waves across the dangerous coral reef. There were 11 fatalities. The survivors camped near collapsed structures from the abortive Arundel coconut plantation and were rescued after several days on the island. The devastated wreck of the Norwich City was a prominent landmark on the reef for 70 years although by 2007 only the ship's keel, engine and two large tanks remained.[11] A Digital Globe satellite image taken November 15, 2016, shows one of the two tanks pushed inland by wave action, and the engine is now gone.[12]

British settlement scheme

On 1 December 1938, members of the British Pacific Islands Survey Expedition arrived to evaluate the island as a possible location for either seaplane landings or an airfield. On 20 December, more British officials arrived with 20 Gilbertese settlers in the last colonial expansion of the British Empire (other than formal annexations preparatory to withdrawal, etc.).[N 2]

The British colonial officer, Gerald Gallagher, established a headquarters of the Phoenix Islands Settlement Scheme in the village located on the island's western end, on the south side of the largest entrance to the lagoon.[N 3] Efforts to clear land and plant coconuts were hindered by a profound lack of drinking water. By June 1939, a few wells had been successfully established and there were 58 I-Kiribati on Gardner, comprising 16 men, 16 women and 26 children. Wide coral-gravel streets and a parade ground were laid out and important structures included a thatched administration house, wood-frame cooperative store and a radio shack. Gallagher died and was buried on the island in 1941.[15]

From 1944 through 1945 the United States Coast Guard operated a navigational LORAN station with 25 crewmen on the southeastern tip of Gardner, installing an antenna system, quonset huts and some smaller structures.[16] Only scattered debris remains on the site.

The island's population reached a high of approximately 100 by the mid-1950s. However, by the early 1960s, periodic drought and an unstable freshwater lens had thwarted the struggling colony. Nikumaroro (together with Manra and Orona) was evacuated by the British government in 1963. Its residents were evacuated to the Solomon Islands by the British and by 1965 Gardner was officially uninhabited.

At his mother's request Gallagher's remains were moved to Tarawa for reburial and the memorial plaque was retrieved.[17] Although reasons cited for giving up on the struggling colony included unstable water lenses and uncertain copra markets, observers familiar with the colony's history remarked that after Gallagher's death a will or nerve to succeed seemed to vanish from the settlements.[17]

The Gardner Island Post Office opened around 1939 and closed around January 1964.[18]

Kiribati

In 1971, the UK granted self-rule to the Gilbert Islands, which achieved complete independence in 1979 as Kiribati. That same year the United States, after having recently surveyed the island for possible weapons testing, relinquished any claims to Gardner through the Treaty of Tarawa. The island was officially renamed Nikumaroro, a name inspired by Gilbertese legends and used by the settlers during the 1940s and 1950s.

Amelia Earhart

Nikumaroro Island is about 640 km (400 mi) southeast of Earhart's intended destination, Howland Island. The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) made several expeditions to Nikumaroro during the 1990s and 2000s.[6][7][19] The group investigated documentary, archaeological and anecdotal evidence supporting a hypothesis that in July 1937, aviators Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan landed on Gardner after failing to find Howland Island during the final stage of their ill-fated world flight. It was surmised that Earhart and Noonan might have survived on Nikumaroro for several weeks before succumbing to injury, starvation, disease or dehydration on the waterless atoll.[19][20] In June 2010, TIGHAR made a 10th expedition to the island.[21]

In an area on the atoll's southeast side called the "Seven Site", the team has found and cataloged artifacts: US beauty and skin care products that may have dated to the 1930s, such as flakes of rouge and a shattered mirror from a woman's cosmetic compact,[22] parts of a folding pocket knife, traces of campfires bearing bird and fish bones, clams opened in the same way as oysters in New England, "empty shells laid out as if to collect rain water" and US bottles dating from before World War II, their heat-warped bottoms showing they "had once stood in a fire as if to boil drinking water."[23] What appeared to be the phalanx bone of a human finger found at the site and examined by forensic anthropologist Karen Ramey Burns has been examined by Dr. Cecil M. Lewis at the Molecular Anthropology Laboratories at the University of Oklahoma in Norman, Oklahoma, USA. DNA tests on the bone fragment proved inconclusive for testing as to whether it is turtle or human.[24] There are many critics of TIGHAR's hypothesis. TIGHAR's Gillespie is credited as a good showman, but solid results are lacking.[25] A curator at the Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum, said, "Not to impugn [the head of TIGHAR], but I don’t think he’s found anything on any expedition".[26]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Since other sources say that family member Joshua Gardner was captain of the Ganges at this time, there is either some confusion in the historical record or both Gardner and Coffin were on board when the island was sighted in 1825.[10]

- ↑ [13] Note: The document contains a detailed description of the British Pacific Islands Survey Expedition.

- ↑ The reference source provides a brief history of Gallagher and the Phoenix Island Settlement Scheme.[14]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Resture, Jane. "Gardner Island (Nikumaroro) Phoenix Group". Jane Resture. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ Howard, Brian Clark (16 June 2014). "Pacific Nation Bans Fishing in One of World's Largest Marine Parks". National Geographic News. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Editor. "Phoenix Islands Protected Area". Government of Kiribati. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ "US reportedly to search again for Amelia Earhart's plane". MSNBC. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Pruitt, Sarah (29 October 2014). "Researchers Identify Fragment of Amelia Earhart’s Plane". history.com. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Niku IIII summary." TIGHAR via tighar.org. Retrieved: 25 October 2009.

- 1 2 "Niku V summary." TIGHAR via tighar.org. Retrieved: 25 October 2009.

- ↑ O'Brien, Mark and Sue Waugh. "Important Bird Areas in the Pacific: A Compendium (CD-ROM)." Secretariat of the Pacific Region Environment Programme. Retrieved: 10 December 2010.

- 1 2 Bryan 1942, p. 71.

- ↑ Dunmore 1992, p. 115.

- ↑ "'Norwich City' photograph and caption." TIGHAR via tighar.org, 2007. Retrieved: 25 October 2009.

- ↑ http://tighar.org/Projects/Earhart/Archives/Research/Bulletins/80_LongFarewell/80_LongFarewellNC.html

- ↑ "The Colonization of the Phoenix Islands." TIGHAR via tighar.org, 2007. Retrieved: 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Gallagher of Nikumaroro: The Last Expansion of the British Empire." TIGHAR via tighar.org, 2007. Retrieved: 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "Archaeology and the fate of Amelia Earhart." archaeology.about.com. Retrieved: 25 October 2009.

- ↑ "USCG LORAN Station." TIGHAR via tighar.org. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- 1 2 King, Thomas, Gallagher of Nikumaroro - The Last Expansion of the British Empire, tighar.org, 1 August 2000, retrieved 14 October 2008. This source is itself supported by over a dozen citations, many of which are primary sources.

- ↑ "Premier Postal History: Post Office List." Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved: 5 July 2013.

- 1 2 Richard Pyle, Group Ends Latest Search for Amelia Earhart, Associated Press (August 2, 2007).

- ↑ Pyle, Richard. Clues to Amelia Earhart’s fate surface, Associated Press (April 1, 2007).

- ↑ "New twist to Amelia Earhart mystery." The Hindu, 28 June 2010. Retrieved: 2 July 2010.

- ↑ Lorenzi, Rossella. "Amelia Earhart's beauty case found? Conclusion to mystery nears." Discovery News, 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Lorenzi, Rossella. "Amelia Earhart's finger bone recovered?" Discovery News, 10 December 2010. Retrieved: 10 December 2010.

- ↑ Gast, Phil. "DNA tests on bone fragment inconclusive in Amelia Earhart search." CNN, 3 March 2011. Retrieved: 3 March 2011.

- ↑ Zwick 2012:"Indeed, Gillespie’s search, the way in which his gifted showmanship has overshadowed the dubiousness of his discoveries and long odds of success, may be the most fitting tribute that the world could offer Earhart on the seventy-fifth anniversary of her death." Zwick quoting Kurt Campbell: "He is by nature a showman and an explorer and an enthusiast."

- ↑ Zwick, Jesse (23 June 2012). "Up in the Air: Hillary Clinton, a lone explorer, and the search for Amelia Earhart.". The New Republic.

Bibliography

- Bryan, Edwin H., Jr. American Polynesia and the Hawaiian Chain. Honolulu, Hawaii: Tongg Publishing Company, 1942.

- Crouch, Thomas D. "Searching for Amelia Earhart." Invention & Technology, Volume 23, Issue 1, Summer 2007.

- Dunmore, John. Who's Who in Pacific Navigation. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-522-84488-X.

- Gillespie, Ric. Finding Amelia: The True Story of the Earhart Disappearance. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2006. ISBN 1-59114-319-5.

- Jones, A.G.E. Ships Employed in the South Seas Trade, 1775–1861 (Part I and II) and Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen Transcripts of Registers of Shipping, 1787–1862 (Part III). Canberra, Australia: Roebuck Society, 1986. ISBN 0-909434-30-1.

- Maude, Henry Evans. Of Islands and Men: Studies in Pacific History. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press, 1968. ISBN 978-0-19-550177-3.

- Reynolds, J.N. Report dated 24 September 1829 in: American State Papers, Documents Legislative and Executive of the Congress of the United States from the Second Session of the Twenty-first to the First Session of the Twenty-fourth Congress... Volume IV Naval Affairs, Document 573, Information Collected by the Navy Department Relating to Islands, Reefs, Shoals etc, in the Pacific Ocean (29 January 1835). Washington, D.C.: Gales's & Seaton, 1861.

- Stackpole, Edouard A. The Sea-Hunters, The New England Whalemen during Two Centuries: 1635–1835. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1953.

- Strippel, Richard G. "Researching Amelia: A Detailed Summary for the Serious Researcher into the Disappearance of Amelia Earhart." Air Classics, Vol. 31, No. 11, November 1995.

External links

- Satellite image of Nikumaroro

- Geographical map of Nikumaroro (Earhart related)

- Earhart Project Hypothesis, Summer 2009

- Forensic Imaging Project II (Earhart related)

- Miamiherald.com: Planned July 2012 search for Earhart

- Tighar.org: Hydrographic Office Chart 125

- Natlib.govt.nz: 1889 Survey catalog entry