Name of Toronto

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Toronto | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Events | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

The name of Toronto has a history distinct from that of the city itself. Originally, the term "Taronto" referred to a channel of water between Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching, but in time the name passed southward, and was eventually applied to a new fort at the mouth of the Humber River. Fort Toronto was the first settlement in the area, and lent its name to what became the city of Toronto.

John Graves Simcoe identified the area as a strategic location to base a new capital for Upper Canada, believing Newark to be susceptible to American invasion. A garrison was established at Garrison Creek, on the western entrance to the docks of Toronto Harbour, in 1793; this later became Fort York. The settlement it defended was renamed York on August 26, 1793, as Simcoe favoured English names over those of First Nations languages,[1] in honour of Prince Frederick, Duke of York.[1] Residents petitioned to change the name back to Toronto, and in 1834 the city was incorporated with its original name.[2] The name York lived on through the name of York County (which was later split into Metropolitan Toronto and York Region), and continues to live on through the names of several districts within the city, including Yorkville, East York, and North York, the latter two suburbs that were formally amalgamated into the "megacity" of Toronto on January 1, 1998.

History

Prior to the Iroquois inhabitation of the Toronto region, the Wyandot (Huron) people inhabited the region, later moving north to the area around Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. The word "toronto", meaning "plenty" appears in a French lexicon of the Huron language in 1632.[3] Toronto however, did not appear on any map of the region before 1650.[3] After 1650, and the destruction of Fort Sainte Marie, the Hurons left the region.[4]

The term "Toronto" became associated with Matchedash Bay, and was recorded with various spellings in French and English, including Tarento, Tarontha, Taronto, Toranto, Torento, Toronto, and Toronton.[5] "Taronto" later referred to "The Narrows", a channel of water through which Lake Simcoe discharges into Lake Couchiching. This narrows was called tkaronto by the Mohawk, meaning "where there are trees standing in the water",[1] and was recorded as early as 1615 by Samuel de Champlain.[6] Today the area is partially surrounded by trees along the water's edge with the rest with marinas and location of the historic Mnjikaning Fish Weirs.

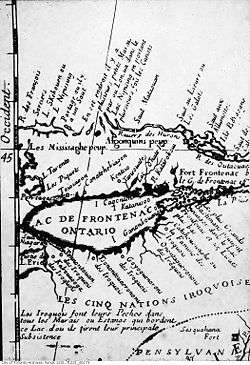

By 1680, Lake Simcoe appeared as Lac de Taronto on a map created by French court official Abbé Claude Bernou; by 1686, Passage de Taronto referred to a canoe route tracking what is now the Humber River. The river became known as Rivière Taronto as the canoe route became more popular with French explorers, and by the 1720s a fort to the east of the delta on Lake Ontario was named by the French Fort Toronto.[1] Rivière Taronto was renamed to Humber River by Simcoe.[1]

The change of spelling from Taronto to Toronto is thought to originate on a 1695 map by Italian cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli.[1]

During his travels in Upper Canada in 1796, Isaac Weld wrote about Simcoe's policy of assigning English names to locations in Upper Canada. He opposed the renaming scheme, stating:[7]

It is to be lamented that the Indian names, so grand and sonorous, should ever have been changed for others. Newark, Kingston, York are poor substitutes for the original names of the respective places Niagara, Cataraqui, Toronto.

The name has also sometimes been identified with Tarantou,[6][8] a village marked on a 1656 map of New France by Nicolas Sanson. However, the location on this map is east of Lake Nipissing and northwest of Montreal in what is now Quebec.[8][9]

Beginnings of Upper Canada

In 1786, Lord Dorchester arrived in Quebec City as Governor-in-Chief of British North America. His mission was to solve the problems of the newly landed Loyalists. At first, Dorchester suggested opening the new Canada West as districts under the Quebec government, but the British Government made known its intention to split Canada into Upper and Lower Canada. Dorchester began organizing for the new province of Upper Canada, including a capital. Dorchester's first choice was Kingston, but was aware of the number of Loyalists in the Bay of Quinte and Niagara areas, and chose instead the location north of the Bay of Toronto, midway between the settlements and 30 miles (48 km) from the US. Under the policy of the time, the British recognized aboriginal title to the land and Dorchester arranged to purchase the lands from the Mississaugas.[10]

Dorchester intended for the location of the new capital to be named Toronto. Instead, Lieutenant Governor Simcoe ordered the name of the new settlement to be called York, after the Duke of York, who had guided a recent British victory in Holland. Simcoe is recorded as both disliking aboriginal names and disliking Dorchester. The new capital was instead named York on August 27, 1793. In 1804, settler Angus MacDonald petitioned the Upper Canada Legislature to restore the name Toronto but this was rejected.[11] To differentiate from York in England and New York City, the town was known as "Little York."[4]

Incorporation of the City of Toronto

In 1834, the Legislative Council sought to incorporate the city, then still known as York. By this time, it was already the largest city in Upper Canada, growing greatly in the late 1820s and early 1830s following the slow growth from its founding in the 1790s. The Council was petitioned to rename the city Toronto during its incorporation, and on March 1, 1834 debated the issue. In Debate on Name Toronto in Incorporation Act, March 1, 1834, records indicate various council members noting their support for or opposition to the measure. The most vocal opponents were John Willson, and Mr. Jarvis and Mr. Bidwell. Proponents were William Chisholm, William Bent Berczy, and Mr. Clark. The Speaker noted that "this city will be the only City of Toronto in the world",[12] to cheers from council.

The name was chosen in part to avoid the negative connotations that "York" had engendered in the city's residents, especially that of dirty Little York. Toronto was also considered more pleasing, as the speaker noted during the debate, "He hoped Honourable Members had the same taste for musical sounds as he had".[13] Berczy noted that "it is the old, original name of the place, and the sound is in every respect much better".[13]

On March 6, 1834, York was officially incorporated as Toronto.

Pronunciation

The stress is on the second syllable; with careful enunciation "Toronto" is pronounced /toʊˈrɒntoʊ/ toh-RON-toh or /təˈrɒntoʊ/ tə-RON-toh. In conversation, locals generally pronounce it /təˈrɒnoʊ/ tə-RON-oh, /ˈtrɒnoʊ/ TRON-oh, /ˈtrɒntoʊ/ TRON-toh, /toʊˈrɒnə/ toh-RON-ə, or /təˈrɒnə/ tə-RON-ə, or, in its most abbreviated form, /ˈtrɒnə/ TRON-ə. As with other words beginning with tr, the stressed /tr/ often sounds almost like [tʃʰʷɹʷ] chr, for pronunciations such as CHRON-oh and CHRON-ə. The same speaker may pronounce "Toronto" differently depending on the subject of the conversation in which it is used.

Canadian francophones say [toʁɔ̃to], with the French nasal on on the second syllable and, if the word is said at the end of a phrase, the stress on the third syllable.

Nicknames

Toronto has garnered various nicknames throughout its history. Among the earliest of these was the disparaging Muddy York, used during the settlement's early growth. At the time, there were no sewers or storm drains, and the streets were unpaved. During rainfall, water would accumulate on the dirt roads, transforming them into often impassable muddy avenues.[14] A more disparaging nickname used by the early residents was Little York,[1] referring to its establishment as a collection of twelve log homes at the mouth of the Don River surrounded by wilderness, and used in comparison to New York City in the United States and York in England. This changed as new settlements and roads were established, extending from the newly established capital.

| “ | ...all roads, all new determinations of settlement radiated from the single muddy street of log houses east of the white-painted wooden church dedicated to St. James, the first representative of the present stately Cathedral... | ” |

| — Toronto: past and present[15] | ||

Adjectives were sometimes attached to Little York; records from the Legislative Council of the time indicate that dirty Little York and nasty Little York were used by residents.[12]

| “ | He hoped the name of Toronto would be adopted, and by that means the inhabitants would not be subjected to the indignity of residing in a place designated "dirty little York". | ” |

| — The Town of York[13] | ||

| “ | It would in some measure meet his notice for a change of the seat of Government as much as could be done this Session, for it would change the name from "Nasty Little York" to the CITY OF TORONTO. | ” |

| — The Town of York[13] | ||

In his book Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names, Alan Rayburn states that "no place in Canada has as many sobriquets as Toronto."[16] Among them are the nicknames:

- "Centre of the Universe",[16] as mentioned in the documentary film Let's All Hate Toronto,[17] as the term is used derisively by residents of the rest of Canada in reference to the city. It is also infrequently used by the media.[18][19][20] Outside Toronto, it is sometimes said to be used by residents of the city.[21] The moniker "Center of the Universe" was originally a popular nickname for New York City, and more specifically Times Square in Midtown Manhattan. It has since been used to refer to other cities.

- "TO" or "T.O.", from Toronto, Ontario, or from Toronto; pronounced "Tee-Oh". Sometimes used as T-dot.[22]

- "The Megacity", referring to the amalgamation of the former Metropolitan Toronto.[23]

- "The City That Works", first mentioned in a Harper's Magazine article written by The Washington Post correspondent Anthony Astrachan in 1975.[16] It refers to the city's reputation for successful urban planning.[24][25][26]

- "The Big Smoke",[27][28][29] used by Allan Fotheringham, a writer for Maclean's magazine, who had first heard the term applied by Aboriginal Australians to Australian cities.[16] The Big Smoke was originally a popular nickname for London, England, and is now used to refer to various cities throughout the world.

- "Hogtown", said to be related to the livestock that was processed in Toronto, largely by the city's largest pork processor and packer, the William Davies Company.[30][31]

- Possibly derived from the Anglo-Saxon word for York, Eoforwic, which literally translates to "wild boar village".

- A by-law which imposed a 10-cent-per-pig fine on anyone allowing pigs to run in the street.[32]

- "Toronto the Good",[33][34] from its history as a bastion of 19th century Victorian morality and coined by mayor William Holmes Howland.[35][36] An 1898 book by C.S. Clark was titled Of Toronto the Good. A Social Study. The Queen City of Canada As It Is.[37] The book is a facsimile of an 1898 edition. Today sometimes used ironically to imply a less-than-great or less-than-moral status.

- "Queen City", a reference now most commonly used by French Canadians ("La Ville-Reine") or speakers of Quebec English,[37][38] other French-language or Franco-Ontarian newsmedia such as Le Droit or in advertising.[39] The second part of the three-part Toronto: City of Dreams documentary about the city was titled The Queen City (1867-1939).[40]

- "Methodist Rome", an analogy identifying the city as a centre for Canadian Methodism.

- "City of Churches".[41]

- "Hollywood North", referring to the film industry.[42][43][44]

- "Broadway North",[16] in reference to the Broadway theatre area in Manhattan. Toronto is home to the world's third largest English-speaking theatre district after London and NYC.[45]

- "The 416", referring to the original telephone area code for much of the city (the other area codes are 647 and 437); the surrounding GTA suburbs, now using area codes 905, 289, and 365, are similarly "the 905".

- "The Six" (also written as "The 6" or "The 6ix") popularized in 2015 by Toronto-born musician, Drake, with his mixtape If You're Reading This It's Too Late and 2016 album Views. Drake himself credits Toronto rapper Jimmy Prime with inventing the handle, but it was used by other Toronto rappers in the early 2000s, in songs such as Baby Blue Soundcrew's "Love 'Em All". The usage of the nickname in many of Drake's songs has since brought it to global attention. While the meaning of the term was initially unclear,[46] Drake clarified in a 2016 interview by Jimmy Fallon on The Tonight Show that it derived from the city's 416 area code and the six municipalities that amalgamated into the modern City of Toronto in 1998.[47]

References

- Benson, Denise. "Putting T-Dot on the Map". Eye Weekly. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- Bly, Laura (September 4, 2009). "Toronto rolls out the red carpet for celebs and U.S. tourists". USA Today. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Cerny, Dory (April 2009). "Earthgirl". Book reviews. Quill & Quire. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Clark, C.S. (1970). Of Toronto the Good. A Social Study. The Queen City of Canada as it is. ISBN 0-665-00659-4. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- Court, Paul. "How Toronto Got Its Names". United States Institute for Theatre Technology, Inc. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- Davidson, Hilary (2007). Frommer's Toronto 2007 (13 ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-04852-8.

- Donald, Betsy (May 16, 2002). "Spinning Toronto's golden age: the making of a 'city that worked'". Environment and Planning A. 34 (12): 2127–2154. ISSN 1472-3409. doi:10.1068/a34111. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Filey, Mark (February 17, 2010). "The rise of the Big Smoke". Toronto Sun. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Firth, Edith G., ed. (1966). The Town of York: 1815—1834; A Further Collection of Documents of Early Toronto. University of Toronto Press.

- Gerard, Warren (2004). "Chronicling a City's Past". Imperial Oil Review. Imperial Oil Limited. 88 (450). Archived from the original on December 17, 2004. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- Guillet, Edwin C. (1969) [1933]. Pioneer Settlements in Upper Canada. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802061109.

- Hare, P.J. "Toronto Pork Packing Plant". Toronto Green Community. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Hayes, Derek (2002). Historical Atlas of Canada: Canada's History Illustrated with Original Maps. Douglas & McIntyre, University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-98277-2.

- Hoang, Na. "Women in Toronto the happiest in Canada?". Canwest News Service.

- Hounsom, Eric Wilfird (1970). Toronto in 1810. Toronto: Ryerson Press. ISBN 0-7700-0311-7.

- Hume, Christopher (October 24, 2009). "A brilliant beauty built to last". Toronto Star. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Kuitenbrouwer, Peter (February 18, 2010). "Toronto is Hollywood North again". National Post. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Low, A. Ritchie (April 20, 1948). "How Good is 'Toronto the Good'?". Baltimore Afro-American. p. M-6. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Maloney, Mark (January 3, 2010). "Toronto's mayors: Scoundrels, rogues and socialists". Toronto Star. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Mendelson, Rachel (December 12, 2013). "Deputy Mayor Norm Kelly says calm has returned to city hall". Toronto Star. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- McCarthy, Pearl (March 5, 1954). "Tarantou, Now Toronto, First Mapped in 1656". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- Mulvany, Charles Pelham (1884). Toronto: past and present: A handbook of the city. W. E. Caiger.

- Rayburn, Alan (2001). Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0.

- Ruppert, Evelyn Sharon (2006). The moral economy of cities: shaping good citizens. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3886-9.

- Stewart, Barry D. (2004). Across the Land: A Canadian Journey of Discovery. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-2276-7.

- Tossell, Ivor (January 30, 2009). "Open-source politics breathe fresh air into the Big Smoke". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "Why, Toronto, you don't look a day over 174...". CBC News. March 6, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "Introduction to Toronto". Frommer's. Wiley Publishing. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "London trumps Toronto as centre of Facebook universe". The Globe and Mail. July 23, 2007. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "Toronto: History". Lonely Planet Publications. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "The real story of how Toronto got its name". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2006.

- "Canada, Provinces & Territories: The naming of their capital cities". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Perly's Toronto Megacity Mapbook". Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2006.

- "Origin of the name of Toronto". City of Toronto. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- "Toronto competes". City of Toronto. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "Entertainment and Tourism". Toronto facts. City of Toronto. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- "Let's All Hate Toronto". The Lens. CBC Newsworld. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Urban Decoder (November 1, 2003). "Toronto is often described as la Ville-Reine (the Queen City) by announcers on Radio-Canada". Toronto Life. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- "Toronto region". Via Rail. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "Part Two: Queen City (1867 - 1939)". Toronto: City of Dreams. White Pine Pictures (at Collections Canada). Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- "We The 6: Why the name Drake gave us is here to stay". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Natural Resources Canada.

- ↑ Court.

- 1 2 Hounsom 1970, p. 26.

- 1 2 Hounsom 1970, p. 27.

- ↑ Guillet 1969, p. 49.

- 1 2 Natural Resources Canada: Canada, Provinces & Territories: The naming of their capital cities.

- 1 2 Guillet 1969, p. 55.

- 1 2 McCarthy 1954, p. 3.

- ↑ Hayes 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Hounsom 1970, pp. xiv-xv.

- ↑ Hounsom 1970, pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 Firth 1966, p. 297–298.

- 1 2 3 4 Firth 1966, p. 297.

- ↑ Gerard 2004.

- ↑ Mulvany 1884, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rayburn 2001, p. 45–48.

- ↑ The LensMister Toronto hurdles through the divide to discover more than he could imagine about the "Centre of the Universe" and the crazy country around it.

- ↑ The Globe and Mail 2007.

- ↑ Cerny 2009.

- ↑ Hoang.

- ↑ Stewart 2004Attitude is something Toronto has lots of. It's not that they actually say they are the "centre of the universe," as that Montreal radio station mentioned. It is just that they "know" it.

- ↑ Benson.

- ↑ Perly's.

- ↑ City of Toronto: Toronto competesGood infrastructure including transit, roads, airports, piped services, public buildings is still a prerequisite to retaining our well earned reputation as the 'city that works' and making our businesses internationally competitive.

- ↑ Lonely PlanetAlthough Toronto is still 'The City That Works', a geeky nickname acquired for its urban planning successes, the new millennium has delivered a lot of headaches so far

- ↑ Donald 2002..key elements of the mode of regulation operating at the urban scale in Toronto's postwar period to learn what it was that inspired an entire generation of scholars to call Toronto the 'city that works' in this period.

- ↑ CBC News 2009The Big Smoke dusted off its party coat on Friday to kick off festivities celebrating Toronto's 175th birthday amid double-digit temperatures.

- ↑ Tossell 2009.

- ↑ Filey 2010.

- ↑ Mendelson 2013.

- ↑ Hare.

- ↑ Macor, Kristie (2010). The Hogtown Project. Toronto, ON: The Hogtown Project. p. Inner cover. ISBN 978-0-9866001-0-4.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Davidson 2007, p. 261It was still a city of churches worthy of the name "Toronto the Good," with a population of staunch religious conservatives, who barely voted for Sunday streetcar service in 1897, and, in 1912, banned tobogganing on Sunday.

- ↑ Low 1948Known to Canadians as 'Toronto the Good," the Ontario metropolis is a thriving city of three-quarters of a million population, of whom four or five thousand are colored.

- ↑ Maloney 2010.

- ↑ Ruppert 2006'Toronto the Good' is one of many popular nicknames used to represent the moral conduct of its citizens. This term was first associated with one of the early examples of reform politics in Toronto: the mayoralty of William Holmes Howland from 1886 to 1888 and his campaign for moral purification (Morton 1973).

- 1 2 Clark 1970.

- ↑ Toronto Life 2003.

- ↑ Via RailWith more than 2.5 million residents, Toronto is Canada’s largest city and the capital of Ontario. The Queen's City is located on the north shore of Lake Ontario and is considered the financial hub of Canada.

- ↑ Toronto: City of Dreams.

- ↑ Hume 2009That landmark heap was built in 1881 by William McMaster as a Baptist college for women, a fitting monument of 19th-century Toronto, then known as the City of Churches.

- ↑ Kuitenbrouwer 2010.

- ↑ Frommer'sChances are that even if you've never set foot here, you've seen the city a hundred times over. Known for the past several years as "Hollywood North," Toronto has been a stand-in for international centres from European capitals to New York -- but rarely does it play itself.

- ↑ Bly 2009Though it vies with Vancouver for the title of Hollywood North, Toronto's active arts and design scene extends far beyond cinema.

- ↑ City of Toronto: Toronto facts.

- ↑ "We The 6: Why the name Drake gave us is here to stay". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ↑ Daniell, Mark (May 13, 2016). "Drake finally explains 'The Six'". Toronto Sun. Postmedia Network. Retrieved February 8, 2017.