First Council of Nicaea

| First Council of Nicaea | |

|---|---|

|

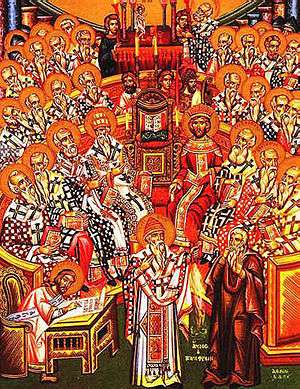

16th-century fresco depicting the Council of Nicaea | |

| Date | 20 May to 19 June, AD 325 |

| Accepted by | |

Next council | First Council of Constantinople |

| Convoked by | Emperor Constantine I |

| President | Hosius of Corduba (and Emperor Constantine)[1] |

| Attendance |

318 (traditional number) 250–318 (estimates) — only five from Western Church |

| Topics | Arianism, the nature of Christ, celebration of Passover (Easter), ordination of eunuchs, prohibition of kneeling on Sundays and from Easter to Pentecost, validity of baptism by heretics, lapsed Christians, sundry other matters.[2] |

Documents and statements | Original Nicene Creed,[3] 20 canons,[4] and a synodal epistle[2] |

| Chronological list of Ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox Churches |

|

Subdivisions

|

|

History and theology

|

|

Major figures

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

Renaissance depiction of the Council of Trent. |

| Classical Antiquity (c. 50) |

| Late Antiquity (325–451) |

| Early Middle Ages (553–870) |

| High and Late Middle Ages (1122–1517) |

| Early Modern and Contemporary (1545–) |

|

|

The First Council of Nicaea (/naɪˈsiːə/; Greek: Νίκαια [ˈni:kaɪja]) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now Iznik, Bursa province, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325. Constantine I organized the Council along the lines of the Roman Senate and presided over it, but did not cast any official vote.

This ecumenical council was the first effort to attain consensus in the Church through an assembly representing all of Christendom. Hosius of Corduba, who was probably one of the Papal legates, may have presided over its deliberations.[5][6]

Its main accomplishments were settlement of the Christological issue of the divine nature of God the Son and his relationship to God the Father,[3] the construction of the first part of the Nicene Creed, establishing uniform observance of the date of Easter,[7] and promulgation of early canon law.[4][8]

Overview

The First Council of Nicaea was the first ecumenical council of the Church. Most significantly, it resulted in the first uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed. With the creation of the creed, a precedent was established for subsequent local and regional councils of Bishops (Synods) to create statements of belief and canons of doctrinal orthodoxy—the intent being to define unity of beliefs for the whole of Christendom.

Derived from Greek (Ancient Greek: οἰκουμένη oikouménē "the inhabited one"), "ecumenical" means "worldwide" but generally is assumed to be limited to the known inhabited Earth, (Danker 2000, pp. 699-670) and at this time in history is synonymous with the Roman Empire; the earliest extant uses of the term for a council are Eusebius' Life of Constantine 3.6[9] around 338, which states "he convoked an Ecumenical Council" (Ancient Greek: σύνοδον οἰκουμενικὴν συνεκρότει sýnodon oikoumenikḕn synekrótei)[10] and the Letter in 382 to Pope Damasus I and the Latin bishops from the First Council of Constantinople.[11]

One purpose of the council was to resolve disagreements arising from within the Church of Alexandria over the nature of the Son in his relationship to the Father: in particular, whether the Son had been 'begotten' by the Father from his own being, and therefore having no beginning, or else created out of nothing, and therefore having a beginning.[12] St. Alexander of Alexandria and Athanasius took the first position; the popular presbyter Arius, from whom the term Arianism comes, took the second. The council decided against the Arians overwhelmingly (of the estimated 250–318 attendees, all but two agreed to sign the creed and these two, along with Arius, were banished to Illyria).[13]

Another result of the council was an agreement on when to celebrate Easter, the most important feast of the ecclesiastical calendar, decreed in an epistle to the Church of Alexandria in which is simply stated:

We also send you the good news of the settlement concerning the holy pasch, namely that in answer to your prayers this question also has been resolved. All the brethren in the East who have hitherto followed the Jewish practice will henceforth observe the custom of the Romans and of yourselves and of all of us who from ancient times have kept Easter together with you.[14]

Historically significant as the first effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom,[15] the Council was the first occasion where the technical aspects of Christology were discussed.[15] Through it a precedent was set for subsequent general councils to adopt creeds and canons. This council is generally considered the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils in the History of Christianity.

Character and purpose

The First Council of Nicaea was convened by Emperor Constantine the Great upon the recommendations of a synod led by Hosius of Córdoba in the Eastertide of 325. This synod had been charged with investigation of the trouble brought about by the Arian controversy in the Greek-speaking east.[16] To most bishops, the teachings of Arius were heretical and dangerous to the salvation of souls.[17] In the summer of 325, the bishops of all provinces were summoned to Nicaea, a place reasonably accessible to many delegates, particularly those of Asia Minor, Georgia, Armenia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and Thrace.

This was the first general council in the history of the Church summoned by emperor Constantine I. In the Council of Nicaea, "The Church had taken her first great step to define revealed doctrine more precisely in response to a challenge from a heretical theology."[18]

Attendees

Constantine had invited all 1,800 bishops of the Christian church within the Roman Empire (about 1,000 in the east and 800 in the west), but a smaller and unknown number attended. Eusebius of Caesarea counted more than 250,[19] Athanasius of Alexandria counted 318,[10] and Eustathius of Antioch estimated "about 270"[20] (all three were present at the council). Later, Socrates Scholasticus recorded more than 300,[21] and Evagrius,[22] Hilary of Poitiers,[23] Jerome,[24] Dionysius Exiguus,[25] and Rufinus[26] recorded 318. This number 318 is preserved in the liturgies of the Eastern Orthodox Church[27] and the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.

Delegates came from every region of the Roman Empire, including Britain.[28] The participating bishops were given free travel to and from their episcopal sees to the council, as well as lodging. These bishops did not travel alone; each one had permission to bring with him two priests and three deacons, so the total number of attendees could have been above 1,800. Eusebius speaks of an almost innumerable host of accompanying priests, deacons, and acolytes.

The Eastern bishops formed the great majority. Of these, the first rank was held by the three patriarchs: Alexander of Alexandria, Eustathius of Antioch, and Macarius of Jerusalem. Many of the assembled fathers—for instance, Paphnutius of Thebes, Potamon of Heraclea, and Paul of Neocaesarea—had stood forth as confessors of the faith and came to the council with the marks of persecution on their faces. This position is supported by patristic scholar Timothy Barnes in his book Constantine and Eusebius.[29] Historically, the influence of these marred confessors has been seen as substantial, but recent scholarship has called this into question.[26]

Other remarkable attendees were Eusebius of Nicomedia; Eusebius of Caesarea, the purported first church historian; circumstances suggest that Nicholas of Myra attended (his life was the seed of the Santa Claus legends); Aristakes of Armenia] (son of Saint Gregory the Illuminator); Leontius of Caesarea; Jacob of Nisibis, a former hermit; Hypatius of Gangra; Protogenes of Sardica; Melitius of Sebastopolis; Achilleus of Larissa (considered the Athanasius of Thessaly)[30] and Spyridion of Trimythous, who even while a bishop made his living as a shepherd.[31] From foreign places came John, bishop of Persia and India, Theophilus, a Gothic bishop, and Stratophilus, bishop of Pitiunt in Georgia.

The Latin-speaking provinces sent at least five representatives: Marcus of Calabria from Italia, Cecilian of Carthage from Africa, Hosius of Córdoba from Hispania, Nicasius of Die from Gaul,[30] and Domnus of Stridon from the province of the Danube.

Athanasius of Alexandria, a young deacon and companion of Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, was among the assistants. Athanasius eventually spent most of his life battling against Arianism. Alexander of Constantinople, then a presbyter, was also present as representative of his aged bishop.[30]

The supporters of Arius included Secundus of Ptolemais, Theonus of Marmarica, Zephyrius (or Zopyrus), and Dathes, all of whom hailed from the Libyan Pentapolis. Other supporters included Eusebius of Nicomedia, Paulinus of Tyrus, Actius of Lydda, Menophantus of Ephesus, and Theognus of Nicaea.[30][32]

"Resplendent in purple and gold, Constantine made a ceremonial entrance at the opening of the council, probably in early June, but respectfully seated the bishops ahead of himself."[5] As Eusebius described, Constantine "himself proceeded through the midst of the assembly, like some heavenly messenger of God, clothed in raiment which glittered as it were with rays of light, reflecting the glowing radiance of a purple robe, and adorned with the brilliant splendor of gold and precious stones."[33] The emperor was present as an overseer and presider, but did not cast any official vote. Constantine organized the Council along the lines of the Roman Senate. Hosius of Cordoba may have presided over its deliberations; he was probably one of the Papal legates.[5] Eusebius of Nicomedia probably gave the welcoming address.[5][34]

Agenda and procedure

The agenda of the synod included:

- The Arian question regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son (not only in his incarnate form as Jesus, but also in his nature before the creation of the world); i.e., are the Father and Son one in divine purpose only or also one in being?

- The date of celebration of Pascha/Easter

- The Meletian schism

- Various matters of church discipline, which resulted in twenty canons

- Organizational structure of the Church: focused on the ordering of the episcopacy

- Dignity standards for the clergy: issues of ordination at all levels and of suitability of behavior and background for clergy

- Reconciliation of the lapsed: establishing norms for public repentance and penance

- Readmission to the Church of heretics and schismatics: including issues of when reordination and/or rebaptism were to be required

- Liturgical practice: including the place of deacons, and the practice of standing at prayer during liturgy[35]

The council was formally opened May 20, in the central structure of the imperial palace at Nicaea, with preliminary discussions of the Arian question. In these discussions, some dominant figures were Arius, with several adherents. "Some 22 of the bishops at the council, led by Eusebius of Nicomedia, came as supporters of Arius. But when some of the more shocking passages from his writings were read, they were almost universally seen as blasphemous."[5] Bishops Theognis of Nicaea and Maris of Chalcedon were among the initial supporters of Arius.

Eusebius of Caesarea called to mind the baptismal creed of his own diocese at Caesarea at Palestine, as a form of reconciliation. The majority of the bishops agreed. For some time, scholars thought that the original Nicene Creed was based on this statement of Eusebius. Today, most scholars think that the Creed is derived from the baptismal creed of Jerusalem, as Hans Lietzmann proposed.

The orthodox bishops won approval of every one of their proposals regarding the Creed. After being in session for an entire month, the council promulgated on June 19 the original Nicene Creed. This profession of faith was adopted by all the bishops "but two from Libya who had been closely associated with Arius from the beginning".[18] No explicit historical record of their dissent actually exists; the signatures of these bishops are simply absent from the Creed.

Arian controversy

The Arian controversy arose in Alexandria when the newly reinstated presbyter Arius[36] began to spread doctrinal views that were contrary to those of his bishop, St. Alexander of Alexandria. The disputed issues centered on the natures and relationship of God (the Father) and the Son of God (Jesus). The disagreements sprang from different ideas about the Godhead and what it meant for Jesus to be God's Son. Alexander maintained that the Son was divine in just the same sense that the Father is, coeternal with the Father, else he could not be a true Son.[12][37]

Arius emphasized the supremacy and uniqueness of God the Father, meaning that the Father alone is almighty and infinite, and that therefore the Father's divinity must be greater than the Son's. Arius taught that the Son had a beginning, and that he possessed neither the eternity nor the true divinity of the Father, but was rather made "God" only by the Father's permission and power, and that the Son was rather the very first and the most perfect of God's creatures.[12][37]

The Arian discussions and debates at the council extended from about May 20, 325, through about June 19.[37] According to legendary accounts, debate became so heated that at one point, Arius was struck in the face by Nicholas of Myra, who would later be canonized.[38] This account is almost certainly apocryphal, as Arius himself would not have been present in the council chamber due to the fact that he was not a bishop.[39]

Much of the debate hinged on the difference between being "born" or "created" and being "begotten". Arians saw these as essentially the same; followers of Alexander did not. The exact meaning of many of the words used in the debates at Nicaea were still unclear to speakers of other languages. Greek words like "essence" (ousia), "substance" (hypostasis), "nature" (physis), "person" (prosopon) bore a variety of meanings drawn from pre-Christian philosophers, which could not but entail misunderstandings until they were cleared up. The word homoousia, in particular, was initially disliked by many bishops because of its associations with Gnostic heretics (who used it in their theology), and because their heresies had been condemned at the 264–268 Synods of Antioch.

Arguments for Arianism

According to surviving accounts, the presbyter Arius argued for the supremacy of God the Father, and maintained that the Son of God was created as an act of the Father's will, and therefore that the Son was a creature made by God, begotten directly of the infinite, eternal God. Arius's argument was that the Son was God's very first production, before all ages. The position being that the Son had a beginning, and that only the Father has no beginning. And Arius argued that everything else was created through the Son. Thus, said the Arians, only the Son was directly created and begotten of God; and therefore there was a time that He had no existence. Arius believed that the Son of God was capable of His own free will of right and wrong, and that "were He in the truest sense a son, He must have come after the Father, therefore the time obviously was when He was not, and hence He was a finite being",[40] and that He was under God the Father. Therefore, Arius insisted that the Father's divinity was greater than the Son's. The Arians appealed to Scripture, quoting biblical statements such as "the Father is greater than I",[41] and also that the Son is "firstborn of all creation".[42]

Arguments against Arianism

The opposing view stemmed from the idea that begetting the Son is itself in the nature of the Father, which is eternal. Thus, the Father was always a Father, and both Father and Son existed always together, eternally, coequally and consubstantially.[43] The contra-Arian argument thus stated that the Logos was "eternally begotten", therefore with no beginning. Those in opposition to Arius believed that to follow the Arian view destroyed the unity of the Godhead, and made the Son unequal to the Father. They insisted that such a view was in contravention of such Scriptures as "I and the Father are one"[44] and "the Word was God",[44] as such verses were interpreted. They declared, as did Athanasius,[45] that the Son had no beginning, but had an "eternal derivation" from the Father, and therefore was coeternal with him, and equal to God in all aspects.[46]

Result of the debate

The Council declared that the Son was true God, coeternal with the Father and begotten from His same substance, arguing that such a doctrine best codified the Scriptural presentation of the Son as well as traditional Christian belief about him handed down from the Apostles. This belief was expressed by the bishops in the Creed of Nicaea, which would form the basis of what has since been known as the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed.[47]

Nicene Creed

One of the projects undertaken by the Council was the creation of a Creed, a declaration and summary of the Christian faith. Several creeds were already in existence; many creeds were acceptable to the members of the council, including Arius. From earliest times, various creeds served as a means of identification for Christians, as a means of inclusion and recognition, especially at baptism.

In Rome, for example, the Apostles' Creed was popular, especially for use in Lent and the Easter season. In the Council of Nicaea, one specific creed was used to define the Church's faith clearly, to include those who professed it, and to exclude those who did not.

Some distinctive elements in the Nicene Creed, perhaps from the hand of Hosius of Cordova, were added, some specifically to counter the Arian point of view.[12][48]

- Jesus Christ is described as "Light from Light, true God from true God," proclaiming his divinity.

- Jesus Christ is said to be "begotten, not made," asserting that he was not a mere creature, brought into being out of nothing, but the true Son of God, brought into being "from the substance of the Father."

- He is said to be "of one being with the Father," proclaiming that although Jesus Christ is "true God" and God the Father is also "true God," they are "of one being," in accord to what is found in John 10:30: "I and the Father are one." The Greek term homoousios, or consubstantial (i.e., "of the same substance) is ascribed by Eusebius of Caesarea to Constantine who, on this particular point, may have chosen to exercise his authority. The significance of this clause, however, is extremely ambiguous as to the extent in which Jesus Christ and God the Father are "of one being," and the issues it raised would be seriously controverted in the future.

At the end of the creed came a list of anathemas, designed to repudiate explicitly the Arians' stated claims.

- The view that "there was once when he was not" was rejected to maintain the coeternity of the Son with the Father.

- The view that he was "mutable or subject to change" was rejected to maintain that the Son just like the Father was beyond any form of weakness or corruptibility, and most importantly that he could not fall away from absolute moral perfection.

Thus, instead of a baptismal creed acceptable to both the Arians and their opponents the council promulgated one which was clearly opposed to Arianism and incompatible with the distinctive core of their beliefs. The text of this profession of faith is preserved in a letter of Eusebius to his congregation, in Athanasius, and elsewhere. Although the most vocal of anti-Arians, the Homoousians (from the Koine Greek word translated as "of same substance" which was condemned at the Council of Antioch in 264–268) were in the minority, the Creed was accepted by the council as an expression of the bishops' common faith and the ancient faith of the whole Church.

Bishop Hosius of Cordova, one of the firm Homoousians, may well have helped bring the council to consensus. At the time of the council, he was the confidant of the emperor in all Church matters. Hosius stands at the head of the lists of bishops, and Athanasius ascribes to him the actual formulation of the creed. Great leaders such as Eustathius of Antioch, Alexander of Alexandria, Athanasius, and Marcellus of Ancyra all adhered to the Homoousian position.

In spite of his sympathy for Arius, Eusebius of Caesarea adhered to the decisions of the council, accepting the entire creed. The initial number of bishops supporting Arius was small. After a month of discussion, on June 19, there were only two left: Theonas of Marmarica in Libya, and Secundus of Ptolemais. Maris of Chalcedon, who initially supported Arianism, agreed to the whole creed. Similarly, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Theognis of Nice also agreed, except for certain statements.

The Emperor carried out his earlier statement: everybody who refused to endorse the Creed would be exiled. Arius, Theonas, and Secundus refused to adhere to the creed, and were thus exiled to Illyria, in addition to being excommunicated. The works of Arius were ordered to be confiscated and consigned to the flames, while his supporters considered as "enemies of Christianity." [49] Nevertheless, the controversy continued in various parts of the empire.[50]

The Creed was amended to a new version by the First Council of Constantinople in 381.

Separation of Easter computation from Jewish calendar

The feast of Easter is linked to the Jewish Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread, as Christians believe that the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus occurred at the time of those observances.

As early as Pope Sixtus I, some Christians had set Easter to a Sunday in the lunar month of Nisan. To determine which lunar month was to be designated as Nisan, Christians relied on the Jewish community. By the later 3rd century some Christians began to express dissatisfaction with what they took to be the disorderly state of the Jewish calendar. They argued that contemporary Jews were identifying the wrong lunar month as the month of Nisan, choosing a month whose 14th day fell before the spring equinox.[51]

Christians, these thinkers argued, should abandon the custom of relying on Jewish informants and instead do their own computations to determine which month should be styled Nisan, setting Easter within this independently computed, Christian Nisan, which would always locate the festival after the equinox. They justified this break with tradition by arguing that it was in fact the contemporary Jewish calendar that had broken with tradition by ignoring the equinox, and that in former times the 14th of Nisan had never preceded the equinox.[52] Others felt that the customary practice of reliance on the Jewish calendar should continue, even if the Jewish computations were in error from a Christian point of view.[53]

The controversy between those who argued for independent computations and those who argued for continued reliance on the Jewish calendar was formally resolved by the Council, which endorsed the independent procedure that had been in use for some time at Rome and Alexandria. Easter was henceforward to be a Sunday in a lunar month chosen according to Christian criteria—in effect, a Christian Nisan—not in the month of Nisan as defined by Jews.[7] Those who argued for continued reliance on the Jewish calendar (called "protopaschites" by later historians) were urged to come around to the majority position. That they did not all immediately do so is revealed by the existence of sermons,[54] canons,[55] and tracts[56] written against the protopaschite practice in the later 4th century.

These two rules, independence of the Jewish calendar and worldwide uniformity, were the only rules for Easter explicitly laid down by the Council. No details for the computation were specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and generated a number of controversies (see also Computus and Reform of the date of Easter.) In particular, the Council did not seem to decree that Easter must fall on Sunday.[57]

Nor did the Council decree that Easter must never coincide with Nisan 14 (the first Day of Unleavened Bread, now commonly called "Passover") in the Hebrew calendar. By endorsing the move to independent computations, the Council had separated the Easter computation from all dependence, positive or negative, on the Jewish calendar. The "Zonaras proviso", the claim that Easter must always follow Nisan 14 in the Hebrew calendar, was not formulated until after some centuries. By that time, the accumulation of errors in the Julian solar and lunar calendars had made it the de facto state of affairs that Julian Easter always followed Hebrew Nisan 14.[58]

Meletian schism

The suppression of the Meletian schism, an early breakaway sect, was another important matter that came before the Council of Nicaea. Meletius, it was decided, should remain in his own city of Lycopolis in Egypt, but without exercising authority or the power to ordain new clergy; he was forbidden to go into the environs of the town or to enter another diocese for the purpose of ordaining its subjects. Melitius retained his episcopal title, but the ecclesiastics ordained by him were to receive again the Laying on of hands, the ordinations performed by Meletius being therefore regarded as invalid. Clergy ordained by Meletius were ordered to yield precedence to those ordained by Alexander, and they were not to do anything without the consent of Bishop Alexander.[59]

In the event of the death of a non-Meletian bishop or ecclesiastic, the vacant see might be given to a Meletian, provided he was worthy and the popular election were ratified by Alexander. As to Meletius himself, episcopal rights and prerogatives were taken from him. These mild measures, however, were in vain; the Meletians joined the Arians and caused more dissension than ever, being among the worst enemies of Athanasius. The Meletians ultimately died out around the middle of the fifth century.

Promulgation of canon law

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Jurisprudence of Catholic canon law |

|---|

|

|

|

Trials and tribunals |

|

Canonical structures Particular churches

|

|

|

The council promulgated twenty new church laws, called canons, (though the exact number is subject to debate), that is, unchanging rules of discipline. The twenty as listed in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers[60] are as follows:

- 1. prohibition of self-castration

- 2. establishment of a minimum term for catechumens (persons studying for baptism)

- 3. prohibition of the presence in the house of a cleric of a younger woman who might bring him under suspicion (the so called virgines subintroductae, who practiced Syneisaktism)

- 4. ordination of a bishop in the presence of at least three provincial bishops and confirmation by the metropolitan bishop

- 5. provision for two provincial synods to be held annually

- 6. confirmation of ancient customs giving jurisdiction over large regions to the bishops of Alexandria, Rome, and Antioch

- 7. recognition of the honorary rights of the see of Jerusalem

- 8. provision for agreement with the Novatianists, an early sect

- 9–14. provision for mild procedure against the lapsed during the persecution under Licinius

- 15–16. prohibition of the removal of priests

- 17. prohibition of usury among the clergy

- 18. precedence of bishops and presbyters before deacons in receiving the Eucharist (Holy Communion)

- 19. declaration of the invalidity of baptism by Paulian heretics

- 20. prohibition of kneeling on Sundays and during the Pentecost (the fifty days commencing on Easter). Standing was the normative posture for prayer at this time, as it still is among the Eastern Christians. Kneeling was considered most appropriate to penitential prayer, as distinct from the festive nature of Eastertide and its remembrance every Sunday. The canon itself was designed only to ensure uniformity of practise at the designated times.

On July 25, 325, in conclusion, the fathers of the council celebrated the Emperor's twentieth anniversary. In his farewell address, Constantine informed the audience how averse he was to dogmatic controversy; he wanted the Church to live in harmony and peace. In a circular letter, he announced the accomplished unity of practice by the whole Church in the date of the celebration of Christian Passover (Easter).

Effects of the council

The long-term effects of the Council of Nicaea were significant. For the first time, representatives of many of the bishops of the Church convened to agree on a doctrinal statement. Also for the first time, the Emperor played a role, by calling together the bishops under his authority, and using the power of the state to give the council's orders effect.

In the short-term, however, the council did not completely solve the problems it was convened to discuss and a period of conflict and upheaval continued for some time. Constantine himself was succeeded by two Arian Emperors in the Eastern Empire: his son, Constantius II and Valens. Valens could not resolve the outstanding ecclesiastical issues, and unsuccessfully confronted St. Basil over the Nicene Creed.[61]

Pagan powers within the Empire sought to maintain and at times re-establish paganism into the seat of the Emperor (see Arbogast and Julian the Apostate). Arians and Meletians soon regained nearly all of the rights they had lost, and consequently, Arianism continued to spread and be a subject of debate within the Church during the remainder of the fourth century. Almost immediately, Eusebius of Nicomedia, an Arian bishop and cousin to Constantine I, used his influence at court to sway Constantine's favor from the proto-orthodox Nicene bishops to the Arians.[62]

Eustathius of Antioch was deposed and exiled in 330. Athanasius, who had succeeded Alexander as Bishop of Alexandria, was deposed by the First Synod of Tyre in 335 and Marcellus of Ancyra followed him in 336. Arius himself returned to Constantinople to be readmitted into the Church, but died shortly before he could be received. Constantine died the next year, after finally receiving baptism from Arian Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, and "with his passing the first round in the battle after the Council of Nicaea was ended".[62]

Role of Constantine

Christianity was illegal in the empire until the emperors Constantine and Licinius agreed in 313 to what became known as the Edict of Milan. However, Nicene Christianity did not become the state religion of the Roman Empire until the Edict of Thessalonica in 380. In the mean time, paganism remained legal and present in public affairs. Constantine's coinage and other official motifs, until the Council of Nicaea, had affiliated him with the pagan cult of Sol Invictus. At first, Constantine encouraged the construction of new temples[63] and tolerated traditional sacrifices.[64] Later in his reign, he gave orders for the pillaging and the tearing down of Roman temples.[65][66][67]

Constantine's role regarding Nicaea was that of supreme civil leader and authority in the empire. As Emperor, the responsibility for maintaining civil order was his, and he sought that the Church be of one mind and at peace. When first informed of the unrest in Alexandria due to the Arian disputes, he was "greatly troubled" and, "rebuked" both Arius and Bishop Alexander for originating the disturbance and allowing it to become public.[68] Aware also of "the diversity of opinion" regarding the celebration of Easter and hoping to settle both issues, he sent the "honored" Bishop Hosius of Cordova (Hispania) to form a local church council and "reconcile those who were divided".[68] When that embassy failed, he turned to summoning a synod at Nicaea, inviting "the most eminent men of the churches in every country".[69]

Constantine assisted in assembling the council by arranging that travel expenses to and from the bishops' episcopal sees, as well as lodging at Nicaea, be covered out of public funds.[70] He also provided and furnished a "great hall ... in the palace" as a place for discussion so that the attendees "should be treated with becoming dignity".[70] In addressing the opening of the council, he "exhorted the Bishops to unanimity and concord" and called on them to follow the Holy Scriptures with: "Let, then, all contentious disputation be discarded; and let us seek in the divinely-inspired word the solution of the questions at issue."[70]

Thereupon, the debate about Arius and church doctrine began. "The emperor gave patient attention to the speeches of both parties" and "deferred" to the decision of the bishops.[71] The bishops first pronounced Arius' teachings to be anathema, formulating the creed as a statement of correct doctrine. When Arius and two followers refused to agree, the bishops pronounced clerical judgement by excommunicating them from the Church. Respecting the clerical decision, and seeing the threat of continued unrest, Constantine also pronounced civil judgement, banishing them into exile. This was the beginning of the practice of using secular power to establish doctrinal orthodoxy within Christianity, an example followed by all later Christian emperors, which led to a circle of Christian violence, and of Christian resistance couched in terms of martyrdom.[72]

Misconceptions

Biblical canon

There is no record of any discussion of the biblical canon at the council.[73] The development of the biblical canon took centuries, and was nearly complete (with exceptions known as the Antilegomena, written texts whose authenticity or value is disputed) by the time the Muratorian fragment was written.[74]

In 331, Constantine commissioned fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople, but little else is known (in fact, it is not even certain whether his request was for fifty copies of the entire Old and New Testaments, only the New Testament, or merely the Gospels). Some scholars believe that this request provided motivation for canon lists. In Jerome's Prologue to Judith,[75] he claims that the Book of Judith was "found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures", which some have suggested means the Nicene Council did discuss what documents would number among the sacred scriptures, but more likely simply means the Council used Judith in its deliberations on other matters and so it should be considered canonical.

The main source of the idea that the Bible was created at the Council of Nicea seems to be Voltaire, who popularised a story that the canon was determined by placing all the competing books on an altar during the Council and then keeping the ones that did not fall off. The original source of this "fictitious anecdote" is the Synodicon Vetus,[76] a pseudo-historical account of early Church councils from AD 887:[77]

The canonical and apocryphal books it distinguished in the following manner: in the house of God the books were placed down by the holy altar; then the council asked the Lord in prayer that the inspired works be found on top and--as in fact happened--the spurious on the bottom.[78]

Trinity

The council of Nicaea dealt primarily with the issue of the deity of Christ. Over a century earlier the term "Trinity" (Τριάς in Greek; trinitas in Latin) was used in the writings of Origen (185–254) and Tertullian (160–220), and a general notion of a "divine three", in some sense, was expressed in the second century writings of Polycarp, Ignatius, and Justin Martyr. In Nicaea, questions regarding the Holy Spirit were left largely unaddressed until after the relationship between the Father and the Son was settled around the year 362.[79] So the doctrine in a more full-fledged form was not formulated until the Council of Constantinople in 360 AD,[80] and a final form formulated in 381 AD, primarily crafted by Gregory of Nyssa.[81]

Constantine

While Constantine had sought a unified church after the council, he did not force the Homoousian view of Christ's nature on the council (see The role of Constantine).

Constantine did not commission any Bibles at the council itself. He did commission fifty Bibles in 331 for use in the churches of Constantinople, itself still a new city. No historical evidence points to involvement on his part in selecting or omitting books for inclusion in commissioned Bibles.

Despite Constantine's sympathetic interest in the Church, he was not baptized until some 11 or 12 years after the council, putting off baptism as long as he did so as to be absolved from as much sin as possible[82] in accordance with the belief that in baptism all sin is forgiven fully and completely.[83]

Disputed matters

Role of the Bishop of Rome

Roman Catholics assert that the idea of Christ's deity was ultimately confirmed by the Bishop of Rome, and that it was this confirmation that gave the council its influence and authority. In support of this, they cite the position of early fathers and their expression of the need for all churches to agree with Rome (see Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses III:3:2).

However, Protestants, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox do not believe the Council viewed the Bishop of Rome as the jurisdictional head of Christendom, or someone having authority over other bishops attending the Council. In support of this, they cite Canon 6, where the Roman Bishop could be seen as simply one of several influential leaders, but not one who had jurisdiction over other bishops in other regions.[84]

According to Protestant theologian Philip Schaff, "The Nicene fathers passed this canon not as introducing anything new, but merely as confirming an existing relation on the basis of church tradition; and that, with special reference to Alexandria, on account of the troubles existing there. Rome was named only for illustration; and Antioch and all the other eparchies or provinces were secured their admitted rights. The bishoprics of Alexandria, Rome, and Antioch were placed substantially on equal footing." Thus, according to Schaff, the Bishop of Alexandria was to have jurisdiction over the provinces of Egypt, Libya and the Pentapolis, just as the Bishop of Rome had authority "with reference to his own diocese." [85]

But according to Fr. James F. Loughlin, there is an alternate Roman Catholic interpretation. It involves five different arguments "drawn respectively from the grammatical structure of the sentence, from the logical sequence of ideas, from Catholic analogy, from comparison with the process of formation of the Byzantine Patriarchate, and from the authority of the ancients"[86] in favor of an alternative understanding of the canon. According to this interpretation, the canon shows the role the Bishop of Rome had when he, by his authority, confirmed the jurisdiction of the other patriarchs—an interpretation which is in line with the Roman Catholic understanding of the Pope. Thus, the Bishop of Alexandria presided over Egypt, Libya and the Pentapolis, while the Bishop of Antioch "enjoyed a similar authority throughout the great diocese of Oriens," and all by the authority of the Bishop of Rome. To Loughlin, that was the only possible reason to invoke the custom of a Roman Bishop in a matter related to the two metropolitan bishops in Alexandria and Antioch.[86]

However, Protestant and Roman Catholic interpretations have historically assumed that some or all of the bishops identified in the canon were presiding over their own dioceses at the time of the Council—the Bishop of Rome over the Diocese of Italy, as Schaff suggested, the Bishop of Antioch over the Diocese of Oriens, as Loughlin suggested, and the Bishop of Alexandria over the Diocese of Egypt, as suggested by Karl Josef von Hefele. According to Hefele, the Council had assigned to Alexandria, "the whole (civil) Diocese of Egypt."[87] Yet those assumptions have since been proven false. At the time of the Council, the Diocese of Egypt did not yet exist, so the Council could not have assigned it to Alexandria. Antioch and Alexandria were both located within the civil Diocese of Oriens, Antioch being the chief metropolis, but neither administered the whole. Likewise, Rome and Milan were both located within the civil Diocese of Italy, Milan being the chief metropolis,[88][89] yet neither administered the whole.

This geographic issue related to Canon 6 was highlighted by Protestant writer, Timothy F. Kauffman, as a correction to the anachronism created by the assumption that each bishop was already presiding over a whole diocese at the time of the council.[90] According to Kauffman, since Milan and Rome were both located within the Diocese of Italy, and Antioch and Alexandria were both located within the Diocese of Oriens, a relevant and "structural congruency" between Rome and Alexandria was readily apparent to the gathered bishops: both had been made to share a diocese of which neither was the chief metropolis. Rome's jurisdiction within Italy had been defined in terms of several of the city's adjacent provinces since Diocletian's reordering of the empire in 293, as the earliest Latin version of the canon indicates,[91] and the rest of the Italian provinces were under the jurisdiction of Milan.

That provincial arrangement of Roman and Milanese jurisdiction within Italy therefore was a relevant precedent, and provided an administrative solution to the problem facing the council—namely, how to define Alexandrian and Antiochian jurisdiction within the Diocese of Oriens. In canon 6, the Council left most of the diocese under Antioch's jurisdiction, and assigned a few provinces of the diocese to Alexandria, "since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also."[92]

In that scenario, a relevant Roman precedent is invoked, answering Loughlin's argument as to why the custom of a bishop in Rome would have any bearing on a dispute regarding Alexandria in Oriens, and at the same time correcting Schaff's argument that the bishop of Rome was invoked by way of illustration "with reference to his own diocese." The custom of the bishop of Rome was invoked by way of illustration, not because he presided over the whole Church, or over the western Church or even over "his own diocese," but rather because he presided over a few provinces in a diocese that was otherwise administered from Milan. On the basis of that precedent, the council recognized Alexandria's ancient jurisdiction over a few provinces in the Diocese of Oriens, a diocese that was otherwise administered from Antioch.

Liturgical commemoration

The Churches of Byzantium celebrate the Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council on the seventh Sunday of Pascha (the Sunday before Pentecost).[93] The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod celebrates the First Ecumenical Council on June 12. The Coptic Church celebrates The Assembly of the First Ecumenical Council on 9 Hathor (usually Nov. 18). The Armenian Church celebrates the 318 Fathers of the Holy Council of Nicaea on Sept. 1.

See also

- Ancient church councils (pre-ecumenical) – church councils before the First Council of Nicaea

- First seven Ecumenical Councils

References

- ↑ Britannica 2014

- 1 2 SEC, pp. 112–114

- 1 2 SEC, p. 39

- 1 2 SEC, pp. 44–94

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carroll 1987, p. 11

- ↑ Dictionnaire Historique, Dominique Vallaud & Fayard,1995, pp. 234–235,678

- 1 2 On the Keeping of Easter

- ↑ Leclercq 1911b

- ↑ Vita Constantini, Book 3, Chapter 6

- 1 2 Ad Afros Epistola Synodica

- ↑ SEC, pp. 292–294

- 1 2 3 4 Kelly 1978, Chapter 9

- ↑ Schaff & Schaff 1910, Section 120

- ↑ SEC, p. 114

- 1 2 Kieckhefer 1989

- ↑ Carroll 1987, p. 10

- ↑ Ware 1991, p. 28

- 1 2 Carroll 1987, p. 12

- ↑ Vita Constantini, iii.7

- ↑ Theodoret, Book 1, Chapter 7

- ↑ Theodoret, Book 1, Chapter 8

- ↑ Theodoret, Book 3, Chapter 31

- ↑ Contra Constantium Augustum Liber

- ↑ Temporum Liber

- ↑ Teres 1984, p. 177

- 1 2 Kelhoffer 2011

- ↑ Pentecostarion

- ↑ "Ancient See of York". New Advent. 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ↑ Barnes 1981, pp. 214–215

- 1 2 3 4 Atiya 1991

- ↑ Vailhé 1912

- ↑ Photius I, Book 1, Chapter 9

- ↑ Vita Constantini, Book 3, Chapter 10

- ↑ Original lists of attendees can be found in Patrum nicaenorum

- ↑ Davis 1983, pp. 63–67

- ↑ Anatolios 2011, p. 44

- 1 2 3 Davis 1983, pp. 52–54

- ↑ OCA 2014

- ↑ González 1984, p. 164

- ↑ M'Clintock & Strong 1890, p. 45

- ↑ John 14:28

- ↑ Colossians 1:15

- ↑ Davis 1983, p. 60

- 1 2 John 10:30

- ↑ On the Incarnation, ch 2, section 9, "... yet He Himself, as the Word, being immortal and the Father's Son"

- ↑ Athanasius (Patriarch of Alexandria) - Select treatises of St. Athanasius in controversy with the Arians, Volume 3 Translator and Editor John Henry Newman. Longmans, Green and co., 1920. page 51. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ González 1984, p. 165

- ↑ Loyn 1991, p. 240

- ↑ Schaff & Schaff 1910, Section 120.

- ↑ Lutz von Padberg 1998, p. 26

- ↑ Anatolius, Book 7, Chapter 33.

- ↑ Chronicon Paschale.

- ↑ Panarion, Book 3, Chapter 1, Section 10.

- ↑ Chrysostom, p. 47.

- ↑ SEC, p. 594.

- ↑ Panarion, Book 3, Chapter 1.

- ↑ Sozomen, Book 7, Chapter 18.

- ↑ L'Huillier 1996, p. 25.

- ↑ Leclercq 1911a

- ↑ Canons

- ↑ AOC 1968

- 1 2 Davis 1983, p. 77

- ↑ Gerberding, R. and J. H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004) p. 28.

- ↑ Peter Brown, The Rise of Christendom 2nd edition (Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2003) p. 60.

- ↑ R. MacMullen, "Christianizing The Roman Empire A.D.100-400, Yale University Press, 1984, ISBN 0-300-03642-6

- ↑ "A History of the Church", Philip Hughes, Sheed & Ward, rev ed 1949, vol I chapter 6.

- ↑ Eusebius Pamphilius and Schaff, Philip (Editor) and McGiffert, Rev. Arthur Cushman, Ph.D. (Translator) NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine quote: "he razed to their foundations those of them which had been the chief objects of superstitious reverence".

- 1 2 Sozomen, Book 1, Chapter 16

- ↑ Sozomen, Book 1, Chapter 17

- 1 2 3 Theodoret, Book 1, Chapter 6

- ↑ Sozomen, Book 1, Chapter 20

- ↑ There is no crime for those who have Christ; religious violence in the Roman Empire. Michael Gaddis. University of California Press 2005. page 340.ISBN 978-0-520-24104-6

- ↑ Ehrman 2004, pp. 15–16, 23, 93

- ↑ McDonald & Sanders 2002, Apendex D2, Note 19

- ↑ Preface to Tobit and Judith

- ↑ Paul T. d' Holbach (1995). Andrew Hunwick, ed. Ecce homo!: An Eighteenth Century Life of Jesus. Critical Edition and Revision of George Houston's Translation from the French. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9783110811414.

- ↑ A concise summary of the case can be found at , or less readable in http://www.tertullian.org/rpearse/nicaea.html .

- ↑ Synodicon Vetus, 35

- ↑ Fairbairn 2009, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Socrates, Book 2, Chapter 41

- ↑ Gregory of Nyssa, The Great Catechism ch. 3 in Schaff, Ante-Nicene, supra, 477

- ↑ Marilena Amerise, 'Il battesimo di Costantino il Grande."

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Vatican. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ Canons, Canon 6

- ↑ Schaff & Schaff 1910, pp. 275–276

- 1 2 Loughlin 1880

- ↑ von Hefele, Karl (1855). Conciliengeschichte, v. 1. Freiburg im Breisgau, Baden-Württemberg, Germany: Herder. p. 373.

- ↑ Athanasius of Alexandria. "Historia Arianorum, Part IV, chapter 36". Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Athanasius of Alexandria. "Apologia de Fuga, chapter 4". Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Kauffman, Timothy F. (May–June 2016). "Nicæa and the Roman Precedent" (PDF). The Trinity Review (334, 335). Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Turner, Cuthberthus Hamilton (1899). Ecclesiae Occidentalis monumenta iuris antiquissima, vol. 1. Oxonii, E Typographeo Clarendoniano. p. 120.

- ↑ First Council of Nicæa. "Canon 6". The First Council of Nicæa. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ https://www.goarch.org/-/sunday-of-the-fathers-of-the-first-ecumenical-council

Bibliography

Primary sources

Note: NPNF2 = Schaff, Philip; Wace, Henry (eds.), Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, retrieved 2014-07-29

- Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, NPNF2, 1, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Anatolius of Laodicea, "Paschal Canons quoted by Eusebius", The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius

- Eusebius Pamphilius, The Life of Constantine [Vita Constantini].

- Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories, NPNF2, 2

- Theodoret, Jerome, Gennadius, and Rufinus: Historical Writings, NPNF2, 3, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Constantine the Great, "Constantinus Augustus to the Churches quoted by Theodoret", The Ecclesiastical History of Theodoret, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Eustathius of Antioch, "A Letter to the African Bishops quoted by Theodoret", The Ecclesiastical History of Theodoret, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Theodoret of Cyrus, The Ecclesiastical History of Theodoret

- Athanasius: Select Works and Letters, NPNF2, 4, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Athanasius of Alexandria, De Decretis [Defence of the Nicene Definition], retrieved 2014-02-24

- Athanasius of Alexandria, Ad Afros Epistola Synodica [Synodal Letter to the Bishops of Africa]

- Eusebius Pamphilus, Letter of Eusebius of Cæsarea to the people of his Diocese, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome, NPNF2, 6, retrieved 2014-02-24

- The Seven Ecumenical Councils, NPNF2, 14

- The Nicene Creed, retrieved 2014-02-24

- The Canons of the 318 Holy Fathers Assembled in the City of Nice, in Bithynia

- Athanasius of Alexandria, The Synodal Letter, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Constantine the Great, "On the Keeping of Easter quoted by Eusebius", The Life of Constantine

- Chronicon Paschale [Paschal Chronicle]

- Pentecostarion, Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain, 3 November 2008, retrieved 22 February 2014

- Chrysostom, John; Harkins, Paul W (trans) (1 April 2010), Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, The Fathers of the Church, 68, Catholic University of America Press, ISBN 978-0-8132-1168-8

- Epiphanius of Salamis; Williams, Frank (trans) (1994), The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-09898-4

- Hilary of Poitiers, Contra Constantium Augustum Liber [A Book Against the Emperor Constantine]

- Jerome, Temporum Liber [The Book of Times]

- Photios I of Constantinople; Walford, Edward (trans), Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, Compiled by Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople

Secondary sources

- "Heroes of the Fourth Century", Word Magazine, Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America: 15–19, February 1968

- "Council of Nicaea", Encyclopædia Britannica, 2014

- Anatolios, Khaled (1 October 2011), Retrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian Doctrine, Grand Rapids: Baker Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8010-3132-8

- Ayers, Lewis (20 April 2006), Nicaea and Its Legacy, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-875505-0, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Barnes, Timothy David (1981), Constantine and Eusebius: , Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-16530-4, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Carroll, Warren (1 March 1987), The Building of Christendom, Front Royal: Christendom College Press, ISBN 978-0-93-188824-3, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Danker, Frederick William (2000), "οἰκουμένη", A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Third ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-03933-6, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Davis, Leo Donald (1983), The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787), Collegeville: Liturgical Press, ISBN 978-0-8146-5616-7, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Edwards, Mark (2009). Catholicity and Heresy in the Early Church. Ashgate.

- Ehrman, Bart (2004), Truth and Fiction in the Da Vinci Code, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-1-28084-545-1

- Fairbairn, Donald (28 September 2009), Life in the Trinity, Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, ISBN 978-0-8308-3873-8, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Gelzer, Heinrich; Hilgenfeld, Henricus; Cuntz, Otto, eds. (1995), Patrum nicaenorum nomina Latine, Graece, Coptice, Syriace, Arabice, Armeniace [The names of the Fathers at Nicaea in Latin, in Greek, Coptic, Syriac, Arabic, Armenian] (2nd ed.), Stuttgart: Teubner

- González, Justo L (1984), The Story of Christianity, 1, Peabody: Prince Press, ISBN 978-1-56563-522-7, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Kelhoffer, James A (2011), "The Search for Confessors at the Council of Nicaea", Journal of Early Christian Studies, 19 (4): 589–599, ISSN 1086-3184, doi:10.1353/earl.2011.0053

- Kelly, J N D (29 March 1978), Early Christian Doctrine, San Francisco: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-064334-8, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Kelly, J N D (1981), Early Christian Creeds, Harlow: Addison-Wesley Longman Limited, ISBN 978-0-582-49219-6, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Kieckhefer, Richard (1989), "Papacy", in Strayer, Joseph Reese, Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 9, Charles Scribner's Sons, ISBN 978-0-684-18278-0, retrieved 2014-02-24

- L'Huillier, Peter (January 1996), The Church of the Ancient Councils: The Disciplinary Work of the First Four Ecumenical Councils, Crestwood: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, ISBN 978-0-88141-007-5, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Leclercq, Henri (1911), "Meletius of Lycopolis", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 10, New York: Robert Appleton Company, retrieved 19 February 2014

- Leclercq, Henri (1911), "The First Council of Nicaea", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 11, New York: Robert Appleton Company, retrieved 19 February 2014

- Loughlin, James F (1880), "The Sixth Nicene Canon and the Papacy", The American Catholic Quarterly Review, 5: 220–239

- Loyn, Henry Royston (1991), The Middle Ages, New York: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-27645-7, retrieved 2014-02-24

- M'Clintock, John; Strong, James (1890), Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, 6, Harper & Brothers, retrieved 2014-02-24

- MacMullen, Ramsay (2006), Voting About God in Early Church Councils, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11596-3, retrieved 2014-02-24

- McDonald, Lee Martin; Sanders, James A, eds. (2002), The Canon Debate, Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, ISBN 978-1-56563-517-3

- Newman, Albert Henry (1899), A Manual of Church History, 1, Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, OCLC 853516, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Newman, John Henry; Williams, Rowan (1 September 2001), The Arians of the Fourth Century, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, ISBN 978-0-268-02012-5, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Norris, Richard Alfred (trans) (1980), The Christological Controversy, Sources of Early Christian Thought, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0-8006-1411-9, retrieved 2014-02-24

- St Nicholas the Wonderworker and Archbishop of Myra in Lycia, retrieved 22 February 2014

- Lutz von Padberg (1998), Die Christianisierung Europas im Mittelalter [The Christianization of Europe in the Middle Ages], P. Reclam, ISBN 978-3-15-017015-1, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Rubenstein, Richard E (26 August 1999), When Jesus became God, New York: Harcourt Brace & Co, ISBN 978-0-15-100368-6, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Rusch, William G (trans) (1980), The Trinitarian Controversy, Sources of Early Christian Thought, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0-8006-1410-2, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Schaff, Philip; Schaff, David Schley (1910). History of the Christian Church. 3. New York: C Scribner's Sons.

- Tanner, Norman P (1 May 2001), The Councils of the Church, New York: Crossroad, ISBN 978-0-8245-1904-9, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Teres, Gustav (October 1984), "Time Computations and Dionysius Exiguus", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 15 (3): 177, Bibcode:1984JHA....15..177T, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Vailhé, Siméon (1912), "Tremithus", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 15, New York: Robert Appleton Company, retrieved 2014-02-24

- Ware, Timothy (1991), The Orthodox Church, Penguin Adult

- Williams, Rowan (1987), Arius, London: Darton, Logman & Todd, ISBN 978-0-232-51692-0, retrieved 2014-02-24

External links

- Canons of the Council of Nicaea, Wisconsin Lutheran College

- Updated English Translations of the Creed, Rulings (Canons), and Letters Connected to the Council.

- The Road to Nicaea A descriptive overview of the events of the Council, by John Anthony McGuckin.