Sorafenib

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nexavar |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607051 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 38–49% |

| Protein binding | 99.5% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic oxidation and glucuronidation (CYP3A4 & UGT1A9-mediated) |

| Biological half-life | 25–48 hours |

| Excretion | Faeces (77%) and urine (19%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms |

Nexavar Sorafenib tosylate |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.110.083 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H16ClF3N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 464.825 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

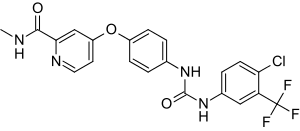

Sorafenib (co-developed and co-marketed by Bayer and Onyx Pharmaceuticals as Nexavar),[1] is a kinase inhibitor drug approved for the treatment of primary kidney cancer (advanced renal cell carcinoma), advanced primary liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma), and radioactive iodine resistant advanced thyroid carcinoma.

Mechanism of action

Sorafenib is a small inhibitor of several tyrosine protein kinases, such as VEGFR, PDGFR and Raf family kinases (more avidly C-Raf than B-Raf).[2][3][4]

(See BRAF (gene)#Sorafenib for details of drug structure interaction with B-Raf.)

Sorafenib treatment induces autophagy,[5] which may suppress tumor growth. However, autophagy can also cause drug resistance.[6]

Medical uses

At the current time sorafenib is indicated as a treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC), unresectable hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) and thyroid cancer.[7][8][9][10]

Kidney cancer

Clinical trial results, published January 2007, showed that, compared with placebo, treatment with sorafenib prolongs progression-free survival in patients with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma in whom previous therapy has failed. The median progression-free survival was 5.5 months in the sorafenib group and 2.8 months in the placebo group (hazard ratio for disease progression in the sorafenib group, 0.44; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.35 to 0.55; P<0.01).[11]

A few reports described patients with stage IV renal cell carcinomas, metastasized to the brain, that were successfully treated with a multimodal approach including neurosurgical, radiation, and sorafenib.[12]

In Australia this is one of two TGA-labelled indications for sorafenib, although it is not listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme for this indication.[10][13]

Liver cancer

At ASCO 2007, results from the SHARP trial[14] were presented, which showed efficacy of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. The primary endpoint was median overall survival, which showed a 44% improvement in patients who received sorafenib compared to placebo (hazard ratio 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.87; p=0.0001). Both median survival and time to progression showed 3-month improvements. There was no difference in quality of life measures, possibly attributable to toxicity of sorafenib or symptoms related to underlying progression of liver disease. Of note, this trial only included patients with Child-Pugh Class A (i.e. mildest) cirrhosis.[14] Because of this trial Sorafenib obtained FDA approval for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in November 2007.[4]

In a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial combining sorafenib with doxorubicin, the median time to progression was not significantly delayed compared with doxorubicin alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Median durations of overall survival and progression-free survival were significantly longer in patients receiving sorafenib plus doxorubicin than in those receiving doxorubicin alone.[4]

A prospective single-centre phase II study which included the patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)concluding that the combination of sorafenib and DEB-TACE in patients with unresectable HCC is well tolerated and safe, with most toxicities related to sorafenib.[15]

In Australia this is the only indication for which sorafenib is listed on the PBS and hence the only Government-subsidised indication for sorafenib.[13] Along with renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma is one of the TGA-labelled indications for sorafenib.[10]

Thyroid cancer

On November 22, 2013, sorafenib was approved by the FDA for the treatment of locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) refractory to radioactive iodine treatment.[16]

The Phase 3 DECISION trial showed significant improvement in progression-free survival but not in overall survival. However, as is known, the side effects were very frequent, specially hand and foot skin reaction.[17]

Desmoid tumors

A phase 3 clinical trial is under way testing the effectiveness of Sorafenib to treat desmoid tumors (also known as aggressive fibromatosis), after positive results in the first two trial stages. Dosage is typically half of that applied for malignant cancers (400 mg vs 800 mg). NCI are sponsoring this trial.[18][19]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects by frequency

Note: Potentially serious side effects are in bold.

Very common (>10% frequency)

- Lymphopenia

- Hypophosphataemia[Note 1]

- Haemorrhage[Note 2]

- Hypertension[Note 3]

- Diarrhea

- Rash

- Alopecia (hair loss; occurs in roughly 30% of patients receiving sorafenib)

- Hand-foot syndrome

- Pruritus (itchiness)

- Erythema

- Increased amylase

- Increased lipase

- Fatigue

- Pain[Note 4]

- Nausea

- Vomiting[Note 5][20]

Common (1-10% frequency)

- Leucopenia[Note 6]

- Neutropoenia[Note 7]

- Anaemia[Note 8]

- Thrombocytopenia[Note 9]

- Anorexia (weight loss)

- Hypocalcaemia[Note 10]

- Hypokalaemia[Note 11]

- Depression

- Peripheral sensory neuropathy

- Tinnitus[Note 12]

- Congestive heart failure

- Myocardial infarction[Note 13]

- Myocardial ischaemia[Note 14]

- Hoarseness

- Constipation

- Stomatitis[Note 15]

- Dyspepsia[Note 16]

- Dysphagia[Note 17]

- Dry skin

- Exfoliative dermatitis

- Acne

- Skin desquamation

- Arthralgia[Note 18]

- Myalgia[Note 19]

- Renal failure[Note 20]

- Proteinuria[Note 21]

- Erectile dysfunction

- Asthenia (weakness)

- Fever

- Influenza-like illness

- Transient increase in transaminase

Uncommon (0.1-1% frequency)

- Folliculitis

- Infection

- Hypersensitivity reactions[Note 22]

- Hypothyroidism[Note 23]

- Hyperthyroidism[Note 24]

- Hyponatraemia[Note 25]

- Dehydration

- Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy

- Hypertensive crisis

- Rhinorrhoea[Note 26]

- Interstitial lung disease-like events[Note 27]

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

- Pancreatitis[Note 28]

- Gastritis[Note 29]

- Gastrointestinal perforations[Note 30]

- Increase in bilirubin leading, potentially, to jaundice[Note 31]

- Cholecystitis[Note 32]

- Cholangitis[Note 33]

- Eczema

- Erythema multiforme[Note 34]

- Keratoacanthoma[Note 35]

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Gynaecomastia (swelling of the breast tissue in men)

- Transient increase in blood alkaline phosphatase

- INR abnormal

- Prothrombin level abnormal

- bulbous skin reaction[21]

Rare (0.01-0.1% frequency)

History

Renal cancer

Sorafenib was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2005,[22] and received European Commission marketing authorization in July 2006,[23] both for use in the treatment of advanced renal cancer.

Liver cancer

The European Commission granted marketing authorization to the drug for the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC), the most common form of liver cancer, in October 2007,[24] and FDA approval for this indication followed in November 2007.[25]

In November 2009, the UK's National Institute of Clinical Excellence declined to approve the drug for use within the NHS in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, stating that its effectiveness (increasing survival in primary liver cancer by 6 months) did not justify its high price, at up to £3000 per patient per month.[26] In Scotland the drug had already been refused authorization by the Scottish Medicines Consortium for use within NHS Scotland, for the same reason.[26]

In March 2012, the Indian Patent Office granted a domestic company, Natco Pharma, a license to manufacture generic Sorafenib, bringing its price down by 97%. Bayer sells a month's supply, 120 tablets, of Nexavar for₹280,000 (US$4,400). Natco Pharma will sell 120 tablets for ₹8,800 (US$140), while still paying a 6% royalty to Bayer. The royalty was later raised to 7% on appeal by Bayer.[27][28][29] Under Indian Patents Act, 2005 and the World Trade Organisation TRIPS Agreement, the government can issue a compulsory license when a drug is not available at an affordable price.[30]

Thyroid cancer

On November 22, 2013, sorafenib was approved by the FDA for the treatment of locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) refractory to radioactive iodine treatment.[16]

Research

Lung

In some kinds of lung cancer (with squamous-cell histology) sorafenib administered in addition to paclitaxel and carboplatin may be detrimental to patients.[31]

Brain (recurrent glioblastoma)

There is a phase I/II study at the Mayo Clinic[32] of sorafenib and CCI-779 (temsirolimus) for recurrent glioblastoma.

Desmoid tumor (aggressive fibromatosis)

A study performed in 2011 showed that Sorafenib is active against aggressive fibromatosis. This study is being used as justification for using Sorafenib as an initial course of treatment in some patients with aggressive fibromatosis.[33]

Nexavar controversy

In January 2014, Bayer's CEO stated that Nexavar was developed for "western patients who [could] afford it". At the prevailing prices, a kidney cancer patient would pay $96,000 (£58,000) for a year's course of the Bayer-made drug. However, the cost of the Indian version of the generic drug would be around $2,800 (£1,700).[34]

Notes

- ↑ Low blood phosphate levels

- ↑ Bleeding; including serious bleeds such as intracranial and intrapulmonary bleeds

- ↑ High blood pressure

- ↑ Including abdominal pain, headache, tumour pain, etc.

- ↑ Considered a low (~10-30%) risk chemotherapeutic agent for causing emesis)

- ↑ Low level of white blood cells in the blood

- ↑ Low level of neutrophils in the blood

- ↑ Low level of red blood cells in the blood

- ↑ Low level of plasma cells in the blood

- ↑ Low blood calcium

- ↑ Low blood potassium

- ↑ Hearing ringing in the ears

- ↑ Heart attack

- ↑ Lack of blood supply for the heart muscle

- ↑ Mouth swelling, also dry mouth and glossodynia

- ↑ Indigestion

- ↑ Not being able to swallow

- ↑ Sore joints

- ↑ Muscle aches

- ↑ Kidney failure

- ↑ Excreting protein [usually plasma proteins] in the urine. Not dangerous in itself but it is indicative kidney damage

- ↑ Including skin reactions and urticaria (hives)

- ↑ Underactive thyroid

- ↑ Overactive thyroid

- ↑ Low blood sodium

- ↑ Runny nose

- ↑ Pneumonitis, radiation pneumonitis, acute respiratory distress, etc.

- ↑ Swelling of the pancreas

- ↑ Swelling of the stomach

- ↑ Formation of a hole in the gastrointestinal tract, leading to potentially fatal bleeds

- ↑ Yellowing of the skin and eyes due to a failure of the liver to adequately cope with the amount of bilirubin produced by the day-to-day actions of the body

- ↑ Swelling of the gallbladder

- ↑ Swelling of the bile duct

- ↑ A potentially fatal skin reaction

- ↑ A fairly benign form of skin cancer

- ↑ A potentially fatal abnormality in the electrical activity of the heart

- ↑ Swelling of the skin and mucous membranes

- ↑ A potentially fatal allergic reaction

- ↑ Swelling of the liver

- ↑ A potentially fatal skin reaction

- ↑ A potentially fatal skin reaction

- ↑ The rapid breakdown of muscle tissue leading to the build-up of myoglobin in the blood and resulting in damage to the kidneys

References

- ↑ "FDA Approves Nexavar for Patients with Inoperable Liver Cancer" (Press release). FDA. November 19, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ↑ Smalley KS, Xiao M, Villanueva J, Nguyen TK, Flaherty KT, Letrero R, Van Belle P, Elder DE, Wang Y, Nathanson KL, Herlyn M (January 2009). "CRAF inhibition induces apoptosis in melanoma cells with non-V600E BRAF mutations". Oncogene. 28 (1): 85–94. PMC 2898184

. PMID 18794803. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.362.

. PMID 18794803. doi:10.1038/onc.2008.362. - ↑ Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M (October 2008). "Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling". Mol. Cancer Ther. 7 (10): 3129–40. PMID 18852116. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013.

- 1 2 3 Keating GM, Santoro A (2009). "Sorafenib: a review of its use in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma". Drugs. 69 (2): 223–40. PMID 19228077. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969020-00006.

- ↑ Zhang Y (Jan 2014). "Screening of kinase inhibitors targeting BRAF for regulating autophagy based on kinase pathways.". J Mol Med Rep. 9 (1): 83–90. PMID 24213221. doi:10.3892/mmr.2013.1781.

- ↑ Gauthier A (Feb 2013). "Role of sorafenib in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: An update..". Hepatol Res. 43 (2): 147–154. PMC 3574194

. PMID 23145926. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034x.2012.01113.x.

. PMID 23145926. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034x.2012.01113.x. - ↑ "Nexavar (sorafenib) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "NEXAVAR (sorafenib) tablet, film coated [Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.]". DailyMed. Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc. November 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ "Nexavar 200mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Bayer plc. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 "PRODUCT INFORMATION NEXAVAR® (sorafenib tosylate)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Bayer Australia Ltd. 12 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Escudier, B; Eisen, T; Stadler, WM; Szczylik, C; Oudard, S; Siebels, M; Negrier, S; Chevreau, C; Solska, E; Desai, AA; Rolland, F; Demkow, T; Hutson, TE; Gore, M; Freeman, S; Schwartz, B; Shan, M; Simantov, R; Bukowski, RM (January 2007). "Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (2): 125–34. PMID 17215530. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060655.

- ↑ Walid, MS; Johnston, KW (October 2009). "Successful treatment of a brain-metastasized renal cell carcinoma" (PDF). German Medical Science. 7: Doc28. PMC 2775194

. PMID 19911072. doi:10.3205/000087.

. PMID 19911072. doi:10.3205/000087. - 1 2 "Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) -SORAFENIB". Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Australian Government Department of Health. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- 1 2 Llovet; et al. (2008). "Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (4): 378–90. PMID 18650514. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0708857.

- ↑ Pawlik TM, Reyes DK, Cosgrove D, Kamel IR, Bhagat N, Geschwind JF (October 2011). "Phase II trial of sorafenib combined with concurrent transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads for hepatocellular carcinoma". J. Clin. Oncol. 29 (30): 3960–7. PMID 21911714. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.1021.

- 1 2 FDA Approval for Sorafenib Tosylate. Nov 2013

- ↑ ASCO: Sorafenib Halts Resistant Thyroid Cancer. June 2013

- ↑ "Sorafenib Tosylate in Treating Patients With Desmoid Tumors or Aggressive Fibromatosis". Clinicaltrials.gov.

- ↑ Gounder, MM; Lefkowitz, RA; Keohan, ML; D'Adamo, DR; Hameed, M; Antonescu, CR; Singer, S; Stout, K; Ahn, L; Maki, RG (15 June 2011). "Activity of Sorafenib against desmoid tumor/deep fibromatosis.". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (12): 4082–90. PMC 3152981

. PMID 21447727. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-3322.

. PMID 21447727. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-3322. - ↑ "Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. 3 July 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Hagopian, Benjamin (August 2010). "Unusually Severe Bullous Skin Reaction to Sorafenib: A Case Report". Journal of Medical Cases. 1 (1): 1–3. doi:10.4021/jmc112e. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ FDA Approval letter for use of sorafenib in advanced renal cancer

- ↑ European Commission – Enterprise and industry. Nexavar. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ↑ "Nexavar® (Sorafenib) Approved for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Europe" (Press release). Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals and Onyx Pharmaceuticals. October 30, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ↑ FDA Approval letter for use of sorafenib in inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma

- 1 2 "Liver drug 'too expensive'". BBC News. November 19, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.lawyerscollective.org/updates/supreme-court-says-no-to-bayer-upholds-compulsory-license-on-nexavar.html

- ↑ http://www.ipindia.nic.in/ipoNew/compulsory_License_12032012.pdf

- ↑ "Seven days: 9–15 March 2012". Nature. 483 (7389): 250–1. 2012. doi:10.1038/483250a.

- ↑ "India Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005". WIPO. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ↑ "Addition of Sorafenib May Be Detrimental in Some Lung Cancer Patients"

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00329719 for "Sorafenib and Temsirolimus in Treating Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Gounder, MM; Lefkowitz, RA; Keohan, ML; D'Adamo, DR; Hameed, M; Antonescu, CR; Singer, S; Stout, K; Ahn, L; Maki, RG (Jun 2011). "Activity of Sorafenib against desmoid tumor/deep fibromatosis.". Clin Cancer Res. 17: 4082–90. PMC 3152981

. PMID 21447727. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3322.

. PMID 21447727. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3322. - ↑ "'We didn't make this medicine for Indians… we made it for western patients who can afford it'". Daily Mail Reporter. 24 Jan 2014.

External links

- Nexavar.com – Manufacturer's website

- Prescribing Information – includes data from the key studies justifying the use of sorafenib for the treatment of kidney cancer (particularly clear cell renal cell carcinoma, which is associated with the von Hippel-Lindau gene)

- Patient Information from FDA

- Sorafenib in Treating Patients With Soft Tissue Sarcomas

- Sorafenib Sunitinib differences – diagram

- Clinical trial number NCT00217399 at ClinicalTrials.gov – Sorafenib and Anastrozole in Treating Postmenopausal Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer

- Cipla launches Nexavar generic at 1/10 of Bayer's price