New Math

New Mathematics or New Math was a brief, dramatic change in the way mathematics was taught in American grade schools, and to a lesser extent in European countries, during the 1960s.

The phrase is often used now to describe any short-lived fad which quickly became highly discredited.

The name is commonly given to a set of teaching practices introduced in the U.S. shortly after the Sputnik crisis, in order to boost science education and mathematical skill in the population, so that the technological threat of Soviet engineers, reputedly highly skilled mathematicians, could be met.

Overview

Topics introduced in the New Math include modular arithmetic, algebraic inequalities, bases other than 10, matrices, symbolic logic, Boolean algebra, and abstract algebra.[1] All of these topics (with the exception of algebraic inequalities) have been greatly de-emphasized or eliminated in U.S. elementary schools and high schools curricula since the 1960s.

Philosopher and mathematician W.V. Quine wrote that the "rarefied air" of Cantorian set theory was not to be associated with the New Math. According to Quine, the New Math involved merely "the Boolean algebra of classes, hence really the simple logic of general terms."[2]

Praise

Though the New Math did not succeed in its time, it did reflect on great developments occurring in technology.

- Boolean logic, devised by the 19th-century mathematician George Boole, forms the basis of how digital circuits work at the simplest level (see Boolean_algebra#Applications_2; Norman Balabanian; Bradley Carlson (2001). Digital logic design principles. John Wiley; Rajaraman & Radhakrishnan. Introduction To Digital Computer Design, PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.)

- Binary data (bits), which are numbers represented in base 2 format using only 2 symbols, 1 and 0, are the machine level representation of the data managed in digital machines. Today, however, a knowledge of binary is, per se, minimally useful for computer programming, though one must know the principles of Boolean operations that manipulate binary numbers.

- Boolean logic would be later employed in electronic databases. The notion of a relation as used in relational databases is an implementation of the idea of an n-ary relation in set theory. In practice, however, one does not need to know the concept of an n-ary relation to use relational database technology productively, though an understanding of basic Boolean logic is necessary to understand the AND, NOT and OR operators. These operations are also important in advanced search of text databases such as Google or PubMed.

In this and other ways, some of the concepts emphasized in New Math proved to be an important link to the computer revolution. While New Math teachings were not sustained in math classes in the years that followed, selected concepts emphasized in New Math have been incorporated into programming-language courses.

Criticisms

Parents and teachers who opposed the New Math in the U.S. complained that the new curriculum was too far outside of students' ordinary experience and was not worth taking time away from more traditional topics, such as arithmetic. The material also put new demands on teachers, many of whom were required to teach material they did not fully understand. Parents were concerned that they did not understand what their children were learning and could not help them with their studies. In an effort to learn the material, many parents attended their children's classes. In the end, it was concluded that the experiment was not working, and New Math fell out of favor before the end of the decade, though it continued to be taught for years thereafter in some school districts. New Math found some later success in the form of enrichment programs for gifted students from the 1980s onward in Project MEGSSS.[3]

In the Algebra preface of his book Precalculus Mathematics in a Nutshell, Professor George F. Simmons wrote that the New Math produced students who had "heard of the commutative law, but did not know the multiplication table."

In 1965, physicist Richard Feynman wrote in the essay "New Textbooks for the 'New Mathematics'":[4]

If we would like to, we can and do say, 'The answer is a whole number less than 9 and bigger than 6,' but we do not have to say, 'The answer is a member of the set which is the intersection of the set of those numbers which are larger than 6 and the set of numbers which are smaller than 9' ... In the 'new' mathematics, then, first there must be freedom of thought; second, we do not want to teach just words; and third, subjects should not be introduced without explaining the purpose or reason, or without giving any way in which the material could be really used to discover something interesting. I don't think it is worth while teaching such material.

In 1973, Morris Kline published his critical book Why Johnny Can't Add: the Failure of the New Math. It explains the desire to be relevant with mathematics representing something more modern than traditional topics. He says certain advocates of the new topics "ignored completely the fact that mathematics is a cumulative development and that it is practically impossible to learn the newer creations, if one does not know the older ones" (p. 17). Furthermore, noting the trend to abstraction in New Math, Kline says "abstraction is not the first stage, but the last stage, in a mathematical development" (p. 98).

Other countries

In the broader context, reform of school mathematics curricula was also pursued in European countries, such as the United Kingdom (particularly by the School Mathematics Project), and France, where the extremely high prestige of mathematical qualifications was not matched by teaching that connected with contemporary research and university topics. In West Germany the changes were seen as part of a larger process of Bildungsreform. Beyond the use of set theory and different approach to arithmetic, characteristic changes were transformation geometry in place of the traditional deductive Euclidean geometry, and an approach to calculus that was based on greater insight, rather than emphasis on facility.

Again, the changes met with a mixed reception, but for different reasons. For example, the end-users of mathematics studies were at that time mostly in the physical sciences and engineering; and they expected manipulative skill in calculus, rather than more abstract ideas. Some compromises have since been required, given that discrete mathematics is the basic language of computing.

Teaching in the USSR did not experience such extreme upheavals, while being kept in tune, both with the applications and academic trends.

Under A. N. Kolmogorov, the mathematics committee declared a reform of the curricula of grades 4–10, at the time when the school system consisted of 10 grades. The committee found the type of reform in progress in Western countries to be unacceptable; for example, no special topic for sets was accepted for inclusion in school textbooks. Transformation approaches were accepted in teaching geometry, but not to such sophisticated level presented in the textbook produced by Vladimir Boltyansky and Isaak Yaglom.[5]

In Japan, the New Math was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), but not without encountering problems, leading to student-centred approaches.[6]

Popular culture

- Musician and university mathematics lecturer Tom Lehrer wrote a satirical song named "New Math" which revolved around the process of subtracting 173 from 342 in decimal and octal. The song is in the style of a lecture about the general concept of subtraction in arbitrary number systems, illustrated by two simple calculations, and highlights the New Math's emphasis on insight and abstract concepts — as Lehrer put it with an indeterminable amount of seriousness, "In the new approach ... the important thing is to understand what you're doing, rather than to get the right answer." At one point in the song, he notes that "you've got thirteen and you take away seven, and that leaves five... well, six, actually, but the idea is the important thing."

Lehrer's explanation of the two calculations is entirely correct, but presented in such a way (very rapidly, and with many side remarks) as to make it difficult to follow the individually simple steps, thus recreating the bafflement the New Math approach often evoked when apparently simple calculations were presented in a very general manner, which, while mathematically correct and arguably trivial for mathematicians, was likely very confusing to absolute beginners, and even for contemporary adult audiences.[7]

- New Math was the name of a 1970s punk rock band from Rochester, New York.[8]

- In 1965, cartoonist Charles Schulz authored a series of Peanuts strips, which detailed kindergartener Sally's frustrations with New Math. In the first strip, she is depicted puzzling over "sets, one-to-one matching, equivalent sets, non-equivalent sets, sets of one, sets of two, renaming two, subsets, joining sets, number sentences, placeholders." Eventually, she bursts into tears and exclaims, "All I want to know is, how much is two and two?"[9] This series of strips was later adapted for the 1973 Peanuts animated special There's No Time for Love, Charlie Brown. Schulz also drew a one panel illustration of Charlie Brown at his school desk exclaiming, "How do you do New Math problems with an old Math mind?"

- In the "Dog of Death" episode of The Simpsons (which first aired in 1992), the state lottery has grown to a $130 million jackpot, though news anchor Kent Brockman notes that the state school system will ultimately gain fully half of that money through taxes. Principal Skinner is elated, and muses about all of the improvements to the elementary school they can obtain with the new funding, such as history books that reveal how the Korean War ended, and "math books that don't have that base six crap in them!"

- In the 1987 The Cosby Show episode "Dance Mania", Cliff agrees to let Vanessa teach him New Math.[10]

- In the 1990 The Golden Girls episode "All Bets Are Off", Rose states that the fall of St. Olaf never happened but "came pretty close when New Math came along".

- In the 2010 Community episode "Conspiracy Theories and Interior Design", phony math professor "Professor Woolley" when asked what type of math he teaches, he replies "Oh, you know, math. Uh... Numbers. Pi. New math. Um..." before running away.

See also

- André Lichnerowicz – Created 1967 French Lichnerowicz Commission

- Comprehensive School Mathematics Program (CSMP)

- Secondary School Mathematics Curriculum Improvement Study (SSMCIS)

- List of abandoned education methods

- School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG)

References

- ↑ Kline, Morris (1973). Why Johnny Can't Add: The Failure of the New Math. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-394-71981-6.

- ↑ Quine, W.V. (1982). Methods of Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. p. 131.

- ↑ http://megsss.org/

- ↑ http://calteches.library.caltech.edu/2362/1/feynman.pdf

- ↑ http://math.unipa.it/~grim/EMALATY231-240.PDF

- ↑ http://www.researchgate.net/publication/37261895___

- ↑ Jur BruijnsOn (30 August 2014). "The full 'New Math' song by Tom Lehrer animated"

- ↑ Punk Rock In Upstate New York By Henry Weld

- ↑ Peanuts strip from October 2, 1965, on GoComics.com

- ↑ The Cosby Show Episode Synopses

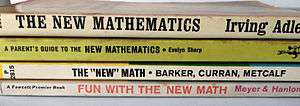

Further reading

- Adler, Irving. The New Mathematics. New York: John Day and Co, 1972 (revised edition). ISBN 0-381-98002-2

- Maurice Mashaal (2006), Bourbaki: A Secret Society of Mathematicians, American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-3967-5, Chapter 10: New Math in the Classroom, pp 134–45.

- Phillips, Christopher J. The New Math: A Political History (2014)