Brooklyn Navy Yard

| Brooklyn Navy Yard | |

|---|---|

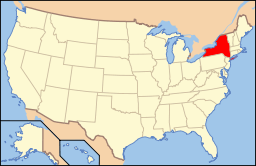

| Brooklyn, New York City, New York | |

|

New York Navy Yard aerial photo April 1945 | |

| Type | Shipyard |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | United States Navy |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1801 |

| In use | 1806–1966 |

| Battles/wars | |

|

Brooklyn Navy Yard Historic District | |

| |

| Location |

Navy Street and Flushing and Kent Avenues Brooklyn, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°42′7.2″N 73°58′8.4″W / 40.702000°N 73.969000°WCoordinates: 40°42′7.2″N 73°58′8.4″W / 40.702000°N 73.969000°W |

| Area | 225.15 acres (91.11 ha) |

| Built | 1801 |

| Architectural style | Early Republic, Mid-19th Century, Late Victorian, Modern Movement |

| NRHP Reference # | 14000261[1] |

| Added to NRHP | 22 May 2014 |

The United States Navy Yard, also known as the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the New York Naval Shipyard (NYNS), was a shipyard located in Brooklyn, New York, 1.7 mi (2.7 km) east of the Battery on the East River in Wallabout Basin, a semicircular bend of the river across from Corlears Hook in Manhattan. It was bounded by Navy Street and Flushing and Kent Avenues, and at the height of its production of warships for the United States Navy, it covered over 200 acres (0.81 km2). The tremendous efforts of its 70,000 workers during World War II earned the yard the nickname "The Can-Do Shipyard."[2]

The yard was decommissioned in 1966.

History

Navy

_at_the_New_York_Navy_Yard.jpg)

Following the American Revolution, the waterfront site was used to build merchant vessels. Federal authorities purchased the old docks and 40 acres (160,000 m2) of land for $40,000 in 1801, and the property became an active US Navy shipyard five years later, in 1806. The offices, storehouses and barracks were constructed of handmade bricks, and the yard's oldest structure (located in Vinegar Hill), the 1807 federal style commandant's house, was designed by Charles Bulfinch, architect of the United States Capitol in Washington, DC. Many officers were housed in Admiral's Row.

Military chain of command was strictly observed. During the yard's construction of Robert Fulton's steam frigate, Fulton, launched in 1815, the year of Fulton's death, the Navy Yard's chief officers were listed as: Captain Commandant, Master Commandant, Lieutenant of the Yard, Master of the Yard, Surgeon of the Yard & Marine Barracks, Purser of the Navy Yard, Naval Storekeeper, Naval Constructor, and a major commanding the Marine Corps detachment.

Civilian Workforce

Early Brooklyn Navy Yard mechanics and laborers were per diem employees, in essence day labor. As such, the workers were subject to the whims of the annual Congressional appropriation and periodic seasonal reduction in the workforce. Like workers everywhere in the early nineteenth century they lived in a constant state of anxiety regarding employment and wage. Wages were subject to considerable change, and in some cases fluctuated dramatically. The following is an example from a letter from Commodore John Rodgers to Captain Samuel Evans dated 24 May 1820. "From and after the 1st day of June 1820 the pay of the Carpenters, Joiners &c in the Yard under your Command must be reduced & regulated by the following rates "carpenters $1.62.5 per day to $ 1.25, blacksmiths 162.5 to 1.12 and laborers 90 cents to 75 cents per day." [3]

The USS Ohio was the first ship of the line built at Brooklyn Navy Yard. She was designed by Henry Eckford, and launched on 30 May 1820.[4] The expansion of shipbuilding led to rapid growth in the labor force as the Navy Yard became New York City's largest employer. In 1848 with 441 employees, wages at the navy yard were relatively high. The median wage of navy yard per diem employees was $1.00 per day. Highly skilled trades such as ship carpenters earned $2.25. The navy yard employees typically worked a ten hour day, six days a week. [5]

The nation's first ironclad ship, Monitor, was fitted with its revolutionary iron cladding at the Continental Iron Works in nearby Greenpoint. By the American Civil War, the yard had expanded to employ thousand of skilled mechanics with men working around the clock. On January 17, 1863 the navy yard station logs reflect 3,933 workers on the payroll,[6] with up to 6000 men by the end of the war. In 1890, the ill-fated Maine was launched from the yard's ways.

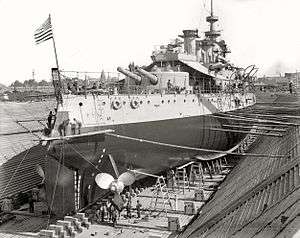

On the eve of World War II, the yard contained more than five miles (8.0 km) of paved streets, four drydocks[7] ranging in length from 326 to 700 ft (99 to 213 m), two steel shipways, and six pontoons and cylindrical floats for salvage work, barracks for marines, a power plant, a large radio station, and a railroad spur, as well as the expected foundries, machine shops, and warehouses. In 1937, the battleship North Carolina was laid down. In 1938, the yard employed about 10,000 men, of whom one-third were Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers. The battleship Iowa was completed in 1942, followed by Missouri, which became the site of the Surrender of Japan on 2 September 1945. On 12 January 1953, test operations began on Antietam, which emerged in December 1952, from the yard as America's first angled-deck aircraft carrier.

At its peak, during World War II, the yard employed 70,000 people, 24 hours a day.

During World War II, the pedestrian walkways on the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges spanning the East River offered a good overhead view of the navy yard, and were therefore encased to prevent espionage.

Brooklyn Naval Hospital

The Brooklyn Naval Hospital, constructed 1830–1838, and rebuilt 1841–1843, was decommissioned in the mid-1970s.[8][9][10] It was one of the oldest naval hospitals in the United States. The 60,000-square-foot (5,600 m2) complex was designed by Martin E. Thompson. The hospital had its beginning in 1825, when the Secretary of the Navy purchased 25 acres (10 ha) adjacent to the Brooklyn Naval Yard. The hospital was active from the Civil War through World War II, with the Navy Surgeon General reporting in 1864, an average of 229 patients, with 2,135 treated during the year. The hospital also counted on its staff some of first female nurses and medical students in the United States Navy.

Closure and commercial usage

A study initiated by the Department of Defense under Robert S. McNamara in late 1963, sought to accomplish savings through the closure of unneeded or excess military installations, especially naval ship yards. On 19 November 1964, based on the study, the closure of the navy yard was announced, along with the Army's Fort Jay on Governors Island and its Brooklyn Army Terminal, all to take effect by 1966. At the time, the yard employed 10,600 civilian employees and 100 military personnel with an annual payroll of about US$90 million. The closure was anticipated to save about 18.1 million dollars annually.[11]

Seymour Melmen, an engineering economist at the Columbia University Graduate School of Engineering, looked into the plight of the shipyard workers at the NYNS and came up with a detailed plan for converting the then naval shipyard into a commercial shipyard which could have saved most of the skilled shipyard jobs. The plan was never put in place. The Wagner Administration looked to the auto industry to build a car plant inside the yard. No US car manufacturer was interested, and foreign car manufacturers claimed that with the conversion of the dollar, it was too expensive. The Navy decommissioned the yard in 1966, after the completion of the Austin-class amphibious transport dock Duluth. The Johnson administration refused to sell the yard to the City of New York for 18 months. When the new Nixon administration came into power, they signed the papers to sell the yard to the city. Leases were signed inside the yard even before the sale to the city was signed.

In 1967, Seatrain Shipbuilding, which was wholly owned by Seatrain Lines, signed a lease with the Commerce Labor Industry Corporation of Kings (CLICK) which was established as a nonprofit body to run the yard for the city. CLICK's lease with the newly formed Seatrain Shipbuilding was not very business friendly. Seatrain planned to build five very large crude carriers (VLCCs) and seven container ships for Seatrain Lines. It eventually built four VLCCs (the largest ships ever to be built in the Brooklyn Navy Yard), eight barges, and one ice-breaker barge. The last ship to be built in the Brooklyn Navy Yard was the VLCC Bay Ridge, built by Seatrain Shipbuilding. In 1977, Bay Ridge was converted from a VLCC to a floating production storage offtake vessel. Bay Ridge was renamed Kuito and is operating for Chevron off of the coast of Angola in 400 m (1,300 ft) of water in the Kuito oil field.[12] Employment inside the yard peaked in 1976, with nearly 6,000 workers with Seatrain Shipbuilding and Coastal Dry Dock and Repair accounting for 80% of the employment.

In 1979, Seatrain Lines closed its gates, ending the history of Brooklyn shipbuilding. In 1972, Coastal Dry Dock and Repair Corp leased the three small dry docks and several buildings inside the yard from CLICK. Coastal Drydock only repaired and converted US Navy vessels, and closed in 1987.[13] CLICK had been replaced by the nonprofit Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation in 1981. By 1987, the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation failed in all attempts to lease any of the six dry docks and buildings to any shipbuilding or ship-repair company.

Current usage

The NYNS has become an area of private manufacturing and commercial activity. Today, more than 200 businesses operate at the yard and employ about 5,000 people.[14] Brooklyn Grange Farms operates a 65,000-square-foot (6,000 m2) commercial farm on top of Building 3.[15] Steiner Studios is one of the yard's tenants with one of the largest production studios outside of Los Angeles. Many artists also lease space and have established an association called Brooklyn Navy Yard Arts.

During the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders held a debate at the Navy Yard.[16] Clinton later held her victory party at the Navy Yard once she clinched the party's nomination.[17]

The NYNS has undertaken a number of construction and renovation projects to expand. The 250,000-square-foot Green Manufacturing Center will be completed in spring of 2016. A renovation of the 1,000,000-square-foot BLDG 77 should be complete in 2016. Construction of Dock 72, a 675,000-square-foot office building, is scheduled to begin in 2015[18] and to be available in 2017.[19]

The NYNS has three piers and a total of 10 berths ranging from 350 to 890 feet (270 m) long, with ten-foot deck height and 25 to 40 feet (7 to 12 m) of depth alongside. The drydocks are now operated by GMD Shipyard Corp. A federal project maintains a channel depth of 35 ft (10 m) from Throggs Neck to the yard, about two mi (3 km) from the western entrance, and thence 40 ft (12 m) of depth to the deep water in the Upper Bay. Currents in the East River can be strong, and congestion heavy. Access to the piers requires passage under the Manhattan Bridge (a suspension span with a clearance of 134 feet (41 m) and the Brooklyn Bridge (a suspension span with a clearance of 127 feet (39 m).

Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92

In November 2011, Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92, a museum dedicated to the yard's history and future, opened.[20][21] A program of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, the center offers exhibits, public tours, educational programs, archival resources, and workforce development services.[22]

The museum's main exhibit focuses on the history of the NYNS and its impact on American industry, technology, innovation, and manufacturing, as well as national and New York City's labor, politics, education, and urban and environmental planning. Also, displays and videos about the new businesses in the facility are seen.

Historic buildings

In 2014, the entire yard was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district,[23] and certain buildings have also been given landmark status. Quarters A, the commander's quarters building, is a National Historic Landmark. The Navy Yard Hospital Building (R95) and Surgeon's Residence (R1) are both designated as NYC Landmark buildings. A report commissioned by the National Guard suggests that the entirety of the Admiral's Row property meets the eligibility criteria for inclusion on the National Register.[24] Admiral's Row has fallen into disrepair and has sparked a landmarks debate.[25]

A bronze marker on the nearby Brooklyn Bridge contains a section commemorating the history of the shipyard, mentioning several of the notable ships that were built there, including Maine, Missouri, and the last ship constructed there, Duluth.[26]

Vinegar Hill and The Navy Yard

There are many plans set forth for the Navy Yard, all of which plan to vitalize the communities around. A Wegman's supermarket is being built. Residents of Vinegar Hill will be able to go to a large supermarket with many fresh produce, currently residents have to go beyond the Navy Yard to get fresh produce.

Commandants (1806–1945)

- Lieutenant Jonathan Thorn, 1 June 1806 – 13 July 1807

- Captain Isaac Chauncey, 13 July 1807 – 16 May 1813

- Captain Samuel Evans, 16 May 1813 – 2 June 1824

- Commander George W. Rodgers, 2 June 1824 – 21 December 1824

- Captain Isaac Chauncey, 21 December 1824 – 10 June 1833

- Captain Charles G. Ridgeley, 10 June 1833 – 19 November 1839

- Captain James Renshaw, 19 November 1839 – 12 June 1841

- Captain Matthew C. Perry, 12 June 1841 – 15 July 1843

- Captain Silas H. Stringham, 15 July 1843 – 1 October 1846

- Captain Isaac McKeever, 1 October 1846 – 1 October 1849

- Captain William D. Salter, 1 October 1849 – 14 October 1852

- Captain Charles Boardman, 14 October 1852 – 1 October 1855

- Captain Abraham Bigelow, 1 October 1855 – 8 June 1857

- Captain Lawrence Kearny, 8 June 1857 – 1 November 1858

- Captain Samuel L. Breese, 1 November 1858 – 25 October 1861

- Captain Hiram Paulding, 25 October 1861 – 1 May 1865

- Commodore Charles H. Bell, 1 May 1865 – 1 May 1868

- Rear Admiral Sylvanus W. Godon, 1 May 1868 – 15 October 1870

- Rear Admiral Melancton Smith, 15 October 1870 – 1 June 1872

- Vice Admiral Stephen Clegg Rowan, 1 June 1872 – 1 September 1876

- Commodore James W. Nicholson, 1 September 1876 – 1 May 1880

- Commodore George H. Cooper, 1 May 1880 – 1 April 1882

- Commodore John H. Upshur, 1 April 1882 – 31 March 1884

- Commodore Thomas S. Fillebrown, 31 March 1884 – 31 December 1884

- Commodore Ralph Chandler, 31 December 1884 – 15 October 1886

- Commodore Bancroft Gherardi, 15 October 1886 – 15 February 1889

- Captain Francis M. Ramsay, 15 February 1889 – 14 November 1889

- Rear Admiral Daniel L. Braine, 14 November 1889 – 20 May 1891

- Commodore Henry Erben, 20 May 1891 – 1 June 1893

- Rear Admiral Bancroft Gherardi, 1 June 1893 – 22 November 1894

- Commodore Montgomery Sicard, 22 November 1894 – 1 May 1897

- Commodore Francis M. Bunce, 1 May 1897 – 14 January 1899

- Commodore John Woodward Philip, 14 January 1899 – 17 July 1900

- Rear Admiral Albert S. Barker, 17 July 1900 – 1 April 1903

- Rear Admiral Frederick Rodgers, 1 April 1903 – 3 October 1904

- Rear Admiral Joseph B. Coghlan, 3 October 1904 – 1 June 1907

- Rear Admiral Caspar F. Goodrich, 1 June 1907 – 15 May 1909

- Captain Joseph B. Murdock, 15 May 1909 – 21 March 1910

- Captain Lewis Sayre Van Duzer, April 1910 - July 1913

- Rear Admiral Eugene H. C. Leutze, 21 March 1910 – 6 June 1912

- Captain Albert Gleaves, 6 June 1912 – 28 September 1914

- Rear Admiral Nathaniel R. Usher, 28 September 1914 – 25 February 1918

- Rear Admiral John D. McDonald, 28 September 1914 – 1 July 1921

- Rear Admiral Carl T. Vogelgesang, 1 July 1921 – 27 November 1922

- Rear Admiral Charles P. Plunkett, 27 November 1922 – 16 February 1928

- Captain Frank Lyon, 16 February 1928 – 2 July 1928

- Rear Admiral Louis R. de Steiguer, 2 July 1928 – 18 March 1931

- Rear Admiral William W. Phelps, 18 March 1931 – 30 June 1933

- Rear Admiral Yates Stirling, Jr., 30 June 1933 – 9 March 1936

- Captain Frederick L. Oliver, 9 March 1936 – 20 April 1936

- Rear Admiral Harris L. Laning, 20 April 1936 – 24 September 1937

- Rear Admiral Clark H. Woodward, 1 October 1937 – 1 March 1941

- Rear Admiral Edward J. Marquart, 2 June 1941 – 2 June 1943

- Rear Admiral Monroe R. Kelly, 2 June 1943 – 5 December 1944

- Rear Admiral Freeland A. Daubin, 5 December 1944 – 25 November 1945

In popular culture

- The New York Naval Shipyard is featured in the 2008 video game Tom Clancy's EndWar, as a playable battlefield. In the game, the NYNS is constructing a new aircraft carrier called the USS Reagan.[27]

- The shipyard is featured in 2000 video game Deus Ex, as a playable level in which the protagonist must scuttle a freighter docked at the base.

- The NYNS is parodied in the 2008 video game, Grand Theft Auto IV, where the game's version of the shipyards is known as the Broker Navy Yard.

- A Harry Houdini-themed task was performed at the NYNS in the final leg of The Amazing Race 21.

- Portions of the 1986 movie Robot Holocaust were filmed at the NYNS.

- The 1997 Caleb Carr novel "Angel of Darkness" (Random House ISBN 0-7515-2275-9) includes scenes that take place in the yard.

See also

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "The Can-Do Yard: WWII at the Brooklyn Navy Yard". BLDG 92. Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ↑ Commodore John Rodgers to Captain Samuel Evans,24 May 1820 re reduction in wage rates RG 125, Records of the Judge Advocate General Case Number 403 Capt. Samuel Evans Entry 26 – B.

John Rodgers to Samuel Evans pay cuts for Brooklyn Navy Yard 1820

John Rodgers to Samuel Evans pay cuts for Brooklyn Navy Yard 1820 - ↑ Albany Gazette (Albany New York) 5 Jun 1820, p. 2.

- ↑ Sharp, John G. Payroll of the Mechanics and Laborers Employed in New York [Brooklyn] Navy Yard 16 to 31 May 1848 http://genealogytrails.com/ny/kings/navyyard.html accessed July 6, 2017

- ↑ Sharp, John G. New York (Brooklyn) Navy Yard Station Logs 1839 - 1863 http://genealogytrails.com/ny/kings/navyyard.html accessed July 6, 2017.

- ↑ NWhyC (20 April 2009). "Dry Dock #1, Brooklyn Navy Yard". Citynoise.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009.

- ↑ "Naval Hospital". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ "Inside the Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital". Gothamist. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ "The Kingston Lounge". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ New York Times, November 20, 1964 page 1

- ↑ "ブーツの似合う脚の条件とは". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ Kennedy, Shawn G. (18 March 1987). "REAL ESTATE; BROOKLYN NAVY YARD PROGRESS". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "The Navy Yard's 'can do' spirit returns to Brooklyn with new businesses, New York Daily News, July 28, 2011". Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ "Clinton, Sanders Tangle Over Gun Control, Israel, Qualifications in Fiery Brooklyn Debate". NY1. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ Gearan, Anne; Costa, Robert; Wagner, John. "Clinton celebrates victory, declaring: ‘We’ve reached a milestone’". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ↑ "Three Huge Construction Projects Happening in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Brownstoner, August 11, 2015". Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ↑ "Dock72 Brooklyn Navy Yard | Brooklyn Coworking Office Space". dock72.com. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- ↑ Matt Flegenheimer (November 6, 2011). "At Long Last, a Glimpse of a Shipbuilding Past". New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "Museum shows why Navy Yard more than just warships, Associated Press, November 26, 2011". Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "About Us". Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places listings for May 30, 2014". U.S. National Park Service. May 30, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ↑ Santora, Marc (14 May 2010). "The Struggle to Preserve the Brooklyn Navy Yard, The New York Times, May 14, 2010". Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ "Panaroma (sic) of Brooklyn South of the Brooklyn Bridge Marker". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ Ubisoft (2008). "Locations". Ubisoft. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

Further reading

- Ships Constructed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

- Inside Brooklyn Navy Yard, 2009 video essay

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brooklyn Navy Yard. |

- The Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation official website

- The Brooklyn Navy Yard collection at the Internet Archive

- Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92 official website