New York Clearing House

The New York Clearing House Association created in 1853, is the first and largest U.S. bank clearing house and has helped the banking system in America’s financial capital to develop. Initially, it simplified the chaotic settlement process among the banks of New York City. It later served to stabilize currency fluctuations and bolster the monetary system through recurring times of panic. Since the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913, it has used technology to meet the demands of an increasingly complex banking system.

History

Founding, 1853

In the decade before the Clearing House was founded, banking had become increasingly complex. From 1849 to 1853 –years highlighted by the California gold rush and construction of a national railroad system–the number of New York banks increased from 24 to 57. Settlement procedures were unsophisticated, with banks settling their accounts by employing porters to travel from bank to bank to exchange checks for bags of coin, or “specie.” As the number of banks grew, exchanges became a daily event. The official reckoning of accounts, however, did not take place until Fridays, often resulting in record keeping errors and encouraging abuses. Each day, the porters would gather on the steps of one of the Wall Street banks for their “Porters’ Exchange.”[1]

In 1853, a bank bookkeeper named George D. Lyman proposed in an article that banks send and receive checks at a central office. There was a positive response and The New York Clearing House was organized officially on October 4 of that year. One week later, on October 11 in the basement of 14 Wall Street, 52 banks participated in the first exchange. On its first day, the Clearing House exchanged checks worth $22.6 million. Within 20 years, the average daily clearing topped $100 million. Today, the average is in excess of $20 billion.[1]

The New York Clearing House brought order to what had been a tangled web of exchanges. Specie certificates soon replaced gold as the means of settling balances at the Clearing House, further simplifying the process. Once certificates were exchanged for gold deposited at member banks, porters encountered fewer of the dangers they had faced previously while transporting bags of gold from bank to bank. Certificates relieved the strain on the bank’s cash flow, thus reducing the likelihood of a run on deposits. Member banks had to do weekly audits, keep minimum reserve levels and log daily settlement of balances which further assured more ordered, efficient exchanges.[1]

Calming the panics, 1853-1913

Between 1853 and 1913, the U.S. experienced rapid economic expansion as well as ten financial panics. One of the Clearing House’s first challenges was the panic of 1857. When the panic began, leaders of the member banks met and devised a plan that would shorten the duration of the panic–and more importantly, maintain public confidence in the banking system. When specie payments were suspended, the Clearing House issued loan certificates that could be used to settle accounts. Known as Clearing House Loan Certificates, they were, in effect, quasi-currency, backed not by gold but by discounted county and state bank notes held by member banks. Bearing the words “Payable Through the Clearing House,” a Clearing House Loan Certificate was the joint liability of all the member banks, and thus, in lieu of specie, a most secure form of payment.[1]

The certificates appeared in smaller denominations during the panic of 1873, and continued to be used as a substitute currency among the member banks for settlement purposes during panics in subsequent decades, including the Panic of 1893. Although they represented a potential violation of federal law against privately issued currencies, these certificates, as a contemporary observer noted, “performed so valuable a service…in moving the crops and keeping business machinery in motion, that the government…wisely forbore to prosecute.”[1]

In 1913, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, thus creating an independent, federal clearing system modeled on the many private clearing houses that had sprung up across America. The new monetary system, with its stringent audits and minimum reserve standards, assumed the role that clearing houses had played.[1]

Clearing process during the 20th century

Since the inception of the Federal Reserve System, the New York Clearing House has concentrated on facilitating the smooth completion of financial transactions by clearing the payments. The clearing process, while highly structured, is in theory, quite simple. Member banks exchange checks, coupons and other certificates of value among themselves, after which the Clearing House records the resulting charges to their accounts. Entries are posted on the books of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to settle any differences. Settlement is prepared each business day at 10:00 a.m. after about three million pieces of paper have been presented for payment.

Computers have been performing the payment clearing that once required paper processing. The Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) began operation in 1970. The New York Automated Clearing House (NYACH) followed in 1975 and became the Electronics Payment Network in 2000. The Clearing House Electronic Check Clearing System (CHECCS) was added in 1992.

See also

References

http://web.archive.org/web/20070821140212/http://www.theclearinghouse.org/docs/000591.pdf

External links

- Official Site

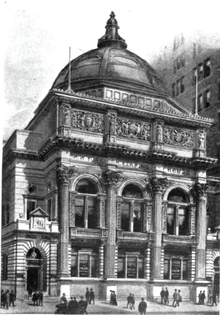

- Laying of the corner stone and opening ceremonies of the new building of the New York Clearing House in Cedar Street. Publisher: J.J. Little & Co., Printers, New York 1896 - Internet Archive - online

- New York Clearing House Association records, 1868-1950 Columbia University Libraries Archival Collection