New England

| New England | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

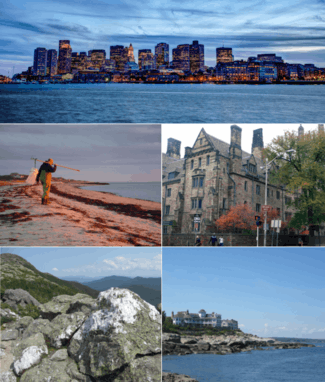

Clockwise from top: skyline of Boston's financial district at night; a building of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut; a view from Nubble Light on Cape Neddick in Maine; view from Mount Mansfield in Vermont; and a fisherman on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. | |||

| |||

| Motto: No official motto, but common de facto mottoes include "An appeal to Heaven" and "Nunquam libertas gratior extat" ("Nowhere does liberty appear in a more gracious form") | |||

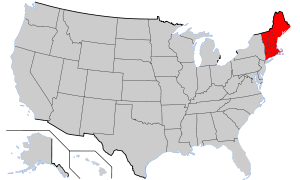

Location of New England (red) in the United States | |||

| Composition | |||

| Largest metropolitan area | |||

| Largest city | Boston | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 71,991.8 sq mi (186,458 km2) | ||

| • Land | 62,688.4 sq mi (162,362 km2) | ||

| Population (2015 est.)[1] | |||

| • Total | 14,727,584 | ||

| • Density | 234.9/sq mi (90.7/km2) | ||

| Demonym(s) | New Englander, Yankee[2] | ||

| GDP (nominal)[3] | |||

| • Total | $953.9 billion (2015) | ||

| Dialects | New England English, New England French | ||

New England is a geographical region comprising six states of the northeastern United States: Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.[lower-alpha 1] It's 'member' states are bordered by the state of New York to the west and south, and by the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north, respectively. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east and southeast, and Long Island Sound is to the south. Boston, the capital of Massachusetts, is New England's largest city. The largest metropolitan area is Greater Boston, which also includes Worcester, Massachusetts (the second-largest city in New England), Manchester (the largest city in New Hampshire), and Providence (the capital and largest city of Rhode Island), with nearly a third of the entire region's population.

In 1620, Puritan Separatist Pilgrims from England first settled in the region, forming the Plymouth Colony, the second successful English settlement in the Americas, following the Jamestown Settlement in Virginia founded in 1607. Ten years later, more Puritans settled north of Plymouth Colony in Boston, thus forming Massachusetts Bay Colony. Over the next 126 years, people in the region fought in four French and Indian Wars, until the British and their Iroquois allies defeated the French and their Algonquin allies in North America. In 1692, the town of Salem, Massachusetts and surrounding areas experienced the Salem witch trials, one of the most infamous cases of mass hysteria in the history of the Western Hemisphere.[10]

In the late 18th century, political leaders from the New England Colonies known as the Sons of Liberty initiated resistance to Britain's efforts to impose new taxes without the consent of the colonists. The Boston Tea Party was a protest to which Britain responded with a series of punitive laws stripping Massachusetts of self-government, which were termed the "Intolerable Acts" by the colonists. The confrontation led to the first battles of the American Revolutionary War in 1775 and the expulsion of the British authorities from the region in spring 1776. The region also played a prominent role in the movement to abolish slavery in the United States, and was the first region of the U.S. transformed by the Industrial Revolution, centered on the Blackstone and Merrimack river valleys.

The physical geography of New England is diverse for such a small area. Southeastern New England is covered by a narrow coastal plain, while the western and northern regions are dominated by the rolling hills and worn-down peaks of the northern end of the Appalachian Mountains. The Atlantic fall line lies close to the coast, which enabled numerous cities to take advantage of water power along the numerous rivers, such as the Connecticut River, which bisects the region from north to south.

Each state is principally subdivided into small incorporated municipalities known as towns, many of which are governed by town meetings. The only unincorporated areas in the region exist in the sparsely populated northern regions of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The region is one of the U.S. Census Bureau's nine regional divisions and the only multi-state region with clear, consistent boundaries. It maintains a strong sense of cultural identity,[11] although the terms of this identity are often contrasted, combining Puritanism with liberalism, agrarian life with industry, and isolation with immigration.

History

Eastern Algonquian peoples

The earliest known inhabitants of New England were American Indians who spoke a variety of the Eastern Algonquian languages.[12] Prominent tribes included the Abenakis, Mi'kmaq, Penobscot, Pequots, Mohegans, Narragansetts, Pocumtucks, and Wampanoag.[12] Prior to the arrival of European settlers, the Western Abenakis inhabited New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont, as well as parts of Quebec and western Maine.[13] Their principal town was Norridgewock in present-day Maine.[14]

The Penobscot lived along the Penobscot River in Maine. The Narragansetts and smaller tribes under Narragansett sovereignty lived in most of modern-day Rhode Island, west of Narragansett Bay, including Block Island. The Wampanoag occupied southeastern Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket. The Pocumtucks lived in Western Massachusetts, and the Mohegan and Pequot tribes lived in the Connecticut region. The Connecticut River Valley includes parts of Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, linking numerous tribes culturally, linguistically, and politically.[12]

As early as 1600, French, Dutch, and English traders began exploring the New World, trading metal, glass, and cloth for local beaver pelts.[12][15]

Colonial period

The Virginia Companies

On April 10, 1606, King James I of England issued a charter for the Virginia Company, which comprised the London Company and the Plymouth Company. These two privately funded ventures were intended to claim land for England, to conduct trade, and to return a profit. In 1620, Pilgrims from the Mayflower established Plymouth Colony in present-day Massachusetts, beginning the history of permanent European settlement in New England.[16]

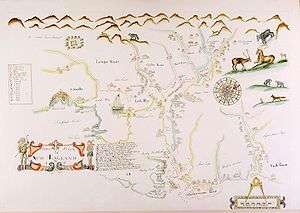

Plymouth Council for New England

In 1616, English explorer John Smith named the region "New England".[17] The name was officially sanctioned on November 3, 1620,[18] when the charter of the Virginia Company of Plymouth was replaced by a royal charter for the Plymouth Council for New England, a joint-stock company established to colonize and govern the region.[19] As the first colonists arrived in Plymouth, they wrote and signed the Mayflower Compact,[20] their first governing document.[21] The Massachusetts Bay Colony came to dominate the area and was established by royal charter in 1629[22][23] with its major town and port of Boston established in 1630.[24]

Massachusetts Puritans began to settle in Connecticut as early as 1633.[25] Roger Williams was banished from Massachusetts for heresy, led a group south, and founded Providence Plantation in the area that became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in 1636.[26][27] At this time, Vermont was yet unsettled, and the territories of New Hampshire and Maine were claimed and governed by Massachusetts.[28]

French and Indian Wars

Relationships between colonists and local Indian tribes alternated between peace and armed skirmishes, the bloodiest of which was the Pequot War in 1637 which resulted in the Mystic massacre.[29] On May 19, 1643, the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, New Haven, and Connecticut joined together in a loose compact called the New England Confederation (officially "The United Colonies of New England"). The confederation was designed largely to coordinate mutual defense, and gained some importance during King Philip's War.[30] From June 1675 through April 1678, King Philip's War pitted the colonists and their Indian allies against a widespread Indian uprising, resulting in killings and massacres on both sides.[31]

During the next 74 years, there were six colonial wars that took place primarily between New England and New France (see the French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). Throughout these wars, New England was allied with the Iroquois Confederacy and New France was allied with the Wabanaki Confederacy. After the New England Conquest of Acadia in 1710, mainland Nova Scotia was under the control of New England, but both present-day New Brunswick and virtually all of present-day Maine remained contested territory between New England and New France. After the British won the war in 1763, the Connecticut River Valley was opened for British settlement into western New Hampshire and what is today Vermont.

The New England colonies were settled primarily by farmers who became relatively self-sufficient. Later, New England's economy began to focus on crafts and trade, aided by the Puritan work ethic, in contrast to the Southern colonies which focused on agricultural production while importing finished goods from England.[32]

Dominion of New England

By 1686, King James II had become concerned about the increasingly independent ways of the colonies, including their self-governing charters, their open flouting of the Navigation Acts, and their growing military power. He therefore established the Dominion of New England, an administrative union comprising all of the New England colonies.[38] In 1688, the former Dutch colonies of New York, East New Jersey, and West New Jersey were added to the Dominion. The union was imposed from the outside and contrary to the rooted democratic tradition of the region, and it was highly unpopular among the colonists.[39]

The Dominion significantly modified the charters of the colonies, including the appointment of Royal Governors to nearly all of them. There was an uneasy tension between the Royal Governors, their officers, and the elected governing bodies of the colonies. The governors wanted unlimited authority, and the different layers of locally elected officials would often resist them. In most cases, the local town governments continued operating as self-governing bodies, just as they had before the appointment of the governors.[40]

After the Glorious Revolution in 1689, Bostonians overthrew royal governor Sir Edmund Andros. They seized dominion officials and adherents to the Church of England during a popular and bloodless uprising.[41] These tensions eventually culminated in the American Revolution, boiling over with the outbreak of the War of American Independence in 1775. The first battles of the war were fought in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, later leading to the Siege of Boston by continental troops. In March 1776, British forces were compelled to retreat from Boston.

New England in the new nation

Post-Revolutionary New England

After the dissolution of the Dominion of New England, the colonies of New England ceased to function as a unified political unit but remained a defined cultural region. By 1784, all of the states in the region had taken steps towards the abolition of slavery, with Vermont and Massachusetts introducing total abolition in 1777 and 1783, respectively.[42] The nickname "Yankeeland" was sometimes used to denote the New England area, especially among Southerners and British.[43]

After settling a dispute with New York, Vermont was admitted to statehood in 1791, formally completing the defined area of New England. On March 15, 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, the territory of Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, was admitted to the Union as a free state.[44] Today, New England is defined as the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.[5]

For the rest of the period before the American Civil War, New England remained distinct from the rest of the United States. New England's economic growth relied heavily on trade with the British Empire,[45] and the region's merchants and politicians strongly opposed trade restrictions. As the United States and the United Kingdom fought the War of 1812, New England Federalists organized the Hartford Convention in the winter of 1814 to discuss the region's grievances concerning the war, and to propose changes to the Constitution to protect the region's interests and maintain its political power.[46] Radical delegates within the convention proposed the region's secession from the United States, but they were outnumbered by moderates who opposed the idea.[47]

Politically, the region often disagreed with the rest of the country.[48] Massachusetts and Connecticut were among the last refuges of the Federalist Party, and New England became the strongest bastion of the new Whig Party when the Second Party System began in the 1830s. The Whigs were usually dominant throughout New England, except in the more Democratic Maine and New Hampshire. Leading statesmen hailed from the region, including Daniel Webster.

New England was distinct in other ways, as well. Many notable literary and intellectual figures were New Englanders, produced by the United States before the American Civil War, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, George Bancroft, and William H. Prescott.[49]

Industrial Revolution

New England was key to the industrial revolution in the United States.[50] The Blackstone Valley, running through Massachusetts and Rhode Island, has been called the birthplace of America's industrial revolution.[51] In 1787, the first cotton mill in America was founded in the North Shore seaport of Beverly, Massachusetts as the Beverly Cotton Manufactory.[52] The Manufactory was also considered the largest cotton mill of its time. Technological developments and achievements from the Manufactory led to the development of more advanced cotton mills, including Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Towns such as Lawrence and Lowell in Massachusetts, Woonsocket in Rhode Island, and Lewiston in Maine became centers of the textile industry following the innovations at Slater Mill and the Beverly Cotton Manufactory.

The Connecticut River Valley - and in particular the Springfield Armory - became a crucible for industrial innovation, pioneering such advances as interchangeable parts and the assembly line, which influenced manufacturing processes all around the world.[53] From early in the nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth, the region surrounding Springfield and Hartford served as the United States' epicenter for precision manufacturing, drawing skilled workers from all over the world.[54][55]

The rapid growth of textile manufacturing in New England between 1815 and 1860 caused a shortage of workers. Recruiters were hired by mill agents to bring young women and children from the countryside to work in the factories. Between 1830 and 1860, thousands of farm girls moved from rural areas where there was no paid employment to work in the nearby mills, such as the famous Lowell Mill Girls. As the textile industry grew, immigration also grew. By the 1850s, immigrants began working in the mills, especially Irish and French Canadians.[56]

New England, as a whole, was the most industrialized part of the young U.S.; by 1850, it accounted for well over a quarter of all manufacturing value in the country and over a third of its industrial workforce.[57] It was also the most literate and most educated region in the country.[57]

Anti-slavery

During the same period, New England and areas settled by New Englanders (upstate New York, Ohio's Western Reserve, and the upper midwestern states of Michigan and Wisconsin) were the center of the strongest abolitionist and anti-slavery movements in the United States, coinciding with the Protestant Great Awakening in the region.[58] Abolitionists who demanded immediate emancipation such as William Lloyd Garrison, John Greenleaf Whittier and Wendell Phillips had their base in the region. So too did anti-slavery politicians who wanted to limit the growth of slavery, such as John Quincy Adams, Charles Sumner, and John P. Hale. When the anti-slavery Republican Party was formed in the 1850s, all of New England, including areas that had previously been strongholds for both the Whig and the Democratic Parties, became strongly Republican. New England remained solidly Republican until Catholics began to mobilize behind the Democrats, especially in 1928, and up until the Republican party realigned its politics in a shift known as the Southern strategy. This led to the end of "Yankee Republicanism" and began New England's relatively swift transition into a consistently Democratic stronghold.[59]

20th century and beyond

The flow of immigrants continued at a steady pace from the 1840s until cut off by World War I. The largest numbers came from Ireland and Britain before 1890, and after that from Quebec, Italy and Southern Europe. The immigrants filled the ranks of factory workers, craftsmen and unskilled laborers. The Irish assumed a larger and larger role in the Democratic Parts in the cities and statewide, while the rural areas remained Republican. Yankees left the farms, which never were highly productive; many headed west, while others became professionals and businessmen in the New England cities.

Great Depression

The Great Depression in the United States of the 1930s hit the region hard, with high unemployment in the industrial cities. The Democrats appealed to factory workers and especially Catholics, pulling them into the New Deal coalition and making the once-Republican region into one that was closely divided. However the enormous spending on munitions, ships, electronics, and uniforms during World War II caused a burst of prosperity in every sector.

Deindustrialization

The region lost most of its factories starting with the loss of textiles in the 1930s and getting worse after 1960. The New England economy was radically transformed after World War II. The factory economy practically disappeared. Like urban centers in the Rust Belt, once-bustling New England communities fell into economic decay following the flight of the region's industrial base. The textile mills one by one went out of business from the 1920s to the 1970s. For example, the Crompton Company, after 178 years in business, went bankrupt in 1984, costing the jobs of 2,450 workers in five states. The major reasons were cheap imports, the strong dollar, declining exports, and a failure to diversify.[60] Shoes followed.

What remains is very high technology manufacturing, such as jet engines, nuclear submarines, pharmaceuticals, robotics, scientific instruments, and medical devices. MIT (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) invented the format for university-industry relations in high tech fields, and spawned many software and hardware firms, some of which grew rapidly.[61] By the 21st century the region had become famous for its leadership roles in the fields of education, medicine and medical research, high-technology, finance, and tourism.[62]

Some industrial areas were slow in adjusting to the new service economy. In 2000, New England had two of the ten poorest cities (by percentage living below the poverty line) in the U.S.: the state capitals of Providence, Rhode Island and Hartford, Connecticut.[63] They were no longer in the bottom ten by 2010; Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire remain among the ten wealthiest states in the United States in terms of median household income and per capita income.[64]

Cities and urban areas

Metropolitan areas

- Bangor, ME MSA

- Barnstable Town, MA MSA (Greater Boston)

- Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH MSA (Greater Boston)

- Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, CT MSA (New York-Newark CSA)

- Burlington-South Burlington, VT MSA

- Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT MSA

- Lewiston-Auburn, ME MSA

- Manchester-Nashua, NH MSA

- New Haven-Milford, CT MSA (New York-Newark CSA)

- Norwich-New London, CT MSA

- Pittsfield, MA MSA

- Portland-South Portland, ME MSA

- Springfield, MA MSA

- Providence-Warwick, RI-MA MSA (Greater Boston)

- Worcester, MA-CT MSA (Greater Boston)

State capitals

- Hartford, Connecticut

- Augusta, Maine

- Boston, Massachusetts

- Concord, New Hampshire

- Providence, Rhode Island

- Montpelier, Vermont

Geography

The states of New England have a combined area of 71,991.8 square miles (186,458 km2), making the region slightly larger than the state of Washington and larger than England.[65][66] Maine alone constitutes nearly one-half of the total area of New England, yet is only the 39th-largest state, slightly smaller than Indiana. The remaining states are among the smallest in the U.S., including the smallest state, Rhode Island.

Geology

New England's long rolling hills, mountains, and jagged coastline are glacial landforms resulting from the retreat of ice sheets approximately 18,000 years ago, during the last glacial period.[67][68]

New England is geologically a part of the New England province, an exotic terrane region consisting of the Appalachian Mountains, the New England highlands, and the seaboard lowlands.[69] The Appalachian Mountains roughly follow the border between New England and New York. The Berkshires in Massachusetts and Connecticut, and the Green Mountains in Vermont, as well as the Taconic Mountains, form a spine of Precambrian rock.[70]

The Appalachians extend northwards into New Hampshire as the White Mountains, and then into Maine and Canada. Mount Washington in New Hampshire is the highest peak in the Northeast, although it is not among the ten highest peaks in the eastern United States.[71] It is the site of the second highest recorded wind speed on Earth,[72][73] and has the reputation of having the world's most severe weather.[74][75]

The coast of the region, extending from southwestern Connecticut to northeastern Maine, is dotted with lakes, hills, marshes and wetlands, and sandy beaches.[68] Important valleys in the region include the Connecticut River Valley and the Merrimack Valley.[68] The longest river is the Connecticut River, which flows from northeastern New Hampshire for 655 km (407 mi), emptying into Long Island Sound, roughly bisecting the region. Lake Champlain, wedged between Vermont and New York, is the largest lake in the region, followed by Moosehead Lake in Maine and Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire.[68]

Climate

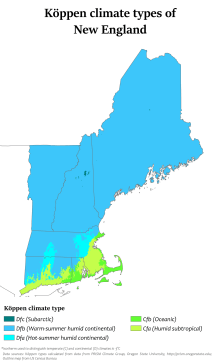

The climate of New England varies greatly across its 500 miles (800 km) span from northern Maine to southern Connecticut:

Maine, northern and central New Hampshire, Vermont, and western Massachusetts have a humid continental climate (Dfb in Köppen climate classification). In this region the winters are long, cold, and heavy snow is common (most locations receive 60 to 120 inches (1,500 to 3,000 mm) of snow annually in this region). The summer's months are moderately warm, though summer is rather short and rainfall is spread through the year.

In central and eastern Massachusetts, southeastern New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and most of Connecticut, the same humid continental prevails (Dfa), though summers are warm to hot, winters are shorter, and there is less snowfall (especially in the coastal areas where it is often warmer).

Southern and coastal Connecticut is the broad transition zone from the cold continental climates of the north to the milder temperate/subtropical climates to the south. The frost free season is greater than 180 days across far southern/coastal Connecticut, coastal Rhode Island, and the islands (Nantucket and Martha's Vineyard). Winters also tend to be much sunnier in southern Connecticut and southern Rhode Island compared to the rest of New England.[76]

Demographics

In 2010, New England had a population of 14,444,865, a growth of 3.8% from 2000.[77] This grew to an estimated 14,727,584 by 2015.[78] Massachusetts is the most populous state with 6,794,422 residents, while Vermont is the least populous state with 626,042 residents.[77] Boston is by far the region's most populous city and metropolitan area.

Although a great disparity exists between New England's northern and southern portions, the region's average population density is 234.93 inhabitants/sq mi (90.7/km²). New England has a significantly higher population density than that of the U.S. as a whole (79.56/sq mi), or even just the contiguous 48 states (94.48/sq mi). Three-quarters of the population of New England, and most of the major cities, are in the states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The combined population density of these states is 786.83/sq mi, compared to northern New England's 63.56/sq mi (2000 census).

According to the 2006–08 American Community Survey, 48.7% of New Englanders were male and 51.3% were female. Approximately 22.4% of the population were under 18 years of age; 13.5% were over 65 years of age. The six states of New England have the lowest birth rate in the U.S.[79]

White Americans make up the majority of New England's population at 83.4% of the total population, Hispanic and Latino Americans are New England's largest minority, and they are the second-largest group in the region behind non-Hispanic European Americans. As of 2014, Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 10.2% of New England's population. Connecticut had the highest proportion at 13.9%, while Vermont had the lowest at 1.3%. There were nearly 1.5 million Hispanic and Latino individuals reported in New England in 2014. Puerto Ricans were the most numerous of the Hispanic and Latino subgroups. Over 660,000 Puerto Ricans lived in New England in 2014, forming 4.5% of the population. The Dominican population is over 200,000, and the Mexican and Guatemalan populations are each over 100,000.[80] Americans of Cuban descent are scant in number; there were roughly 26,000 Cuban Americans in the region in 2014. People of all other Hispanic and Latino ancestries, including Salvadoran, Colombian, and Bolivian, formed 2.5% of New England's population, and numbered over 361,000 combined.[80]

According to the 2014 American Community Survey, the top ten largest reported European ancestries were the following:[81]

- Irish: 19.2% (2.8 million)

- Italian: 13.6% (2.0 million)

- French and French Canadian: 13.1% (1.9 million)

- English: 11.9% (1.7 million)[82]

- German: 7.4% (1.1 million)

- Polish: 4.9% (roughly 715,000)

- Portuguese: 3.2% (467,000)

- Scottish: 2.5% (370,000)

- Russian: 1.4% (206,000)

- Greek: 1.0% (152,000)

English is, by far, the most common language spoken at home. Approximately 81.3% of all residents (11.3 million people) over the age of five spoke only English at home. Roughly 1,085,000 people (7.8% of the population) spoke Spanish at home, and roughly 970,000 people (7.0% of the population) spoke other Indo-European languages at home. Over 403,000 people (2.9% of the population) spoke an Asian or Pacific Island language at home.[83] Slightly fewer (about 1%) spoke French at home,[84] although this figure is above 20% in northern New England, which borders francophone Québec. Roughly 99,000 people (0.7% of the population) spoke languages other than these at home.[83]

As of 2014, approximately 87% of New England's inhabitants were born in the U.S., while over 12% were foreign-born.[85] 35.8% of foreign-born residents were born in Latin America, 28.6% were born in Asia, 22.9% were born in Europe, and 8.5% were born in Africa.[86]

Southern New England forms an integral part of the BosWash megalopolis, a conglomeration of urban centers that spans from Boston to Washington, D.C. The region includes three of the four most densely populated states in the U.S.; only New Jersey has a higher population density than the states of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Greater Boston, which includes parts of southern New Hampshire, has a total population of approximately 4.8 million,[87] while over half the population of New England falls inside Boston's Combined Statistical Area of over 8.2 million.[88]

Largest cities

The most populous cities as of the Census Bureau's 2014 estimates were (metropolitan areas in parentheses):[87][89]

Boston, Massachusetts: 655,884 (4,739,385)

Boston, Massachusetts: 655,884 (4,739,385) Worcester, Massachusetts: 183,016 (931,802)

Worcester, Massachusetts: 183,016 (931,802) Providence, Rhode Island: 179,154 (1,609,533)

Providence, Rhode Island: 179,154 (1,609,533) Springfield, Massachusetts: 153,991 (630,672)

Springfield, Massachusetts: 153,991 (630,672) Bridgeport, Connecticut: 147,612 (945,816)

Bridgeport, Connecticut: 147,612 (945,816) New Haven, Connecticut: 130,282 (861,238)

New Haven, Connecticut: 130,282 (861,238) Stamford, Connecticut: 128,278 (part of Bridgeport's MSA)

Stamford, Connecticut: 128,278 (part of Bridgeport's MSA) Hartford, Connecticut: 124,705 (1,213,225)

Hartford, Connecticut: 124,705 (1,213,225) Manchester, New Hampshire: 110,448 (405,339)

Manchester, New Hampshire: 110,448 (405,339) Lowell, Massachusetts: 109,945 (part of Greater Boston)

Lowell, Massachusetts: 109,945 (part of Greater Boston) Cambridge, Massachusetts: 109,694 (part of Greater Boston)

Cambridge, Massachusetts: 109,694 (part of Greater Boston) Waterbury, Connecticut: 109,307 (part of New Haven's MSA)

Waterbury, Connecticut: 109,307 (part of New Haven's MSA) New Bedford, Massachusetts: 94,845 (part of Providence's MSA)

New Bedford, Massachusetts: 94,845 (part of Providence's MSA) Brockton, Massachusetts: 94,779 (part of Greater Boston)

Brockton, Massachusetts: 94,779 (part of Greater Boston) Quincy, Massachusetts: 93,397 (part of Greater Boston)

Quincy, Massachusetts: 93,397 (part of Greater Boston)

During the 20th century, urban expansion in regions surrounding New York City has become an important economic influence on neighboring Connecticut, parts of which belong to the New York metropolitan area. The U.S. Census Bureau groups Fairfield, New Haven and Litchfield counties in western Connecticut together with New York City, and other parts of New York and New Jersey as a combined statistical area.[90]

- Major Cities of New England

Economy

Overview

Several factors combine to make the New England economy unique. The region is distant from the geographic center of the country, and is a relatively small region, and relatively densely populated. It historically has been an important center of industrial manufacturing and a supplier of natural resource products, such as granite, lobster, and codfish. New England exports food products, ranging from fish to lobster, cranberries, Maine potatoes, and maple syrup. The service industry is important, including tourism, education, financial and insurance services, plus architectural, building, and construction services. The U.S. Department of Commerce has called the New England economy a microcosm for the entire U.S. economy.[91]

In the first half of the 20th century, the region underwent a long period of deindustrialization as traditional manufacturing companies relocated to the Midwest, with textile and furniture manufacturing migrating to the South. In the mid-to-late 20th century, an increasing portion of the regional economy included high technology (including computer and electronic equipment manufacturing), military defense industry, finance and insurance services, as well as education and health services.

As of 2015, the GDP of New England was $953.9 billion.[92]

Exports

Exports consist mostly of industrial products, including specialized machines and weaponry (aircraft and missiles especially), built by the region's educated workforce. About half of the region's exports consist of industrial and commercial machinery, such as computers and electronic and electrical equipment. This, when combined with instruments, chemicals, and transportation equipment, makes up about three-quarters of the region's exports. Granite is quarried at Barre, Vermont,[93] guns made at Springfield, Massachusetts and Saco, Maine, boats at Groton, Connecticut and Bath, Maine, and hand tools at Turners Falls, Massachusetts. Insurance is a driving force in and around Hartford, Connecticut.[91]

Agriculture

Agriculture is limited by the area's rocky soil, cool climate, and small area. Some New England states, however, are ranked highly among U.S. states for particular areas of production. Maine is ranked ninth for aquaculture,[94] and has abundant potato fields in its northeast part. Vermont is fifteenth for dairy products,[95] and Connecticut and Massachusetts seventh and eleventh for tobacco, respectively.[96][97] Cranberries are grown in Massachusetts' Cape Cod-Plymouth-South Shore area, and blueberries in Maine.

Energy

Three of the six New England states are among the country's highest consumers of nuclear power: Vermont (first, 73.7%), Connecticut (fourth, 48.9%), and New Hampshire (sixth, 46%).[98] The region is mostly energy-efficient compared to the U.S. at large, with every state but Maine ranking within the ten most energy-efficient states;[99] every state in New England also ranks within the ten most expensive states for electricity prices.[100]

Employment

| Employment area | October 2010 | October 2011 | October 2012 | October 2013 | December 2014 | December 2015[101] | December 2016[102] | Net change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 9.7 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.7 | −5.0 |

| New England | 8.3 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 3.5 | −4.7 |

| Connecticut | 9.1 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 7.6 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 4.4 | −4.7 |

| Maine | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 3.8 | −3.8 |

| Massachusetts | 8.3 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 2.8 | −5.5 |

| New Hampshire | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 2.6 | −3.1 |

| Rhode Island | 11.5 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 9.4 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 5.0 | −6.5 |

| Vermont | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 3.1 | −2.8 |

As of January 2017, employment is stronger in New England than in the rest of the United States. During the Great Recession, unemployment rates ballooned across New England as elsewhere; however, in the years that followed, these rates declined steadily, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts having the lowest unemployment rates in the country, respectively. The most extreme swing was in Rhode Island, which had an unemployment rate above 10% following the recession, but which saw this rate decline by over 6% in six years.

As of December 2016, the metropolitan statistical area (MSA) with the lowest unemployment rate, 2.1%, was Burlington-South Burlington, Vermont; the MSA with the highest rate, 4.9%, was Waterbury, Connecticut.[103]

Government

Town meetings

New England town meetings were derived from meetings held by church elders, and are still an integral part of government in many New England towns. At such meetings, any citizen of the town may discuss issues with other members of the community and vote on them. This is the strongest example of direct democracy in the U.S. today, and the strong democratic tradition was even apparent in the early 19th century, when Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America:

| “ | New England, where education and liberty are the daughters of morality and religion, where society has acquired age and stability enough to enable it to form principles and hold fixed habits, the common people are accustomed to respect intellectual and moral superiority and to submit to it without complaint, although they set at naught all those privileges which wealth and birth have introduced among mankind. In New England, consequently, the democracy makes a more judicious choice than it does elsewhere.[104] | ” |

By contrast, James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 55 that, regardless of the assembly, "passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob."[105] The use and effectiveness of town meetings is still discussed by scholars, as well as the possible application of the format to other regions and countries.[106]

Politics

Elections

State and national elected officials in New England recently have been elected mainly from the Democratic Party.[107] The region is generally considered to be the most liberal in the United States, with more New Englanders identifying as liberals than Americans elsewhere. In 2010, four of six of the New England states were polled as the most liberal in the United States; Maine and New Hampshire also were more liberal than the bottom-half.[108]

The six states of New England voted for the Democratic Presidential nominee in the 1992, 1996, 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2016 elections, and every New England state other than New Hampshire voted for Al Gore in the presidential election of 2000. In the 113th Congress the House delegations from all six states of New England were all Democratic. New England is home to the only two independents currently serving in the U.S. Senate, both of whom caucus with the Democratic Party: Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist,[109][110] representing Vermont; and Angus King, an Independent representing Maine.

In the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama carried all six New England states by 9 percentage points or more.[111] He carried every county in New England except for Piscataquis County, Maine, which he lost by 4% to Senator John McCain (R-AZ). Pursuant to the reapportionment following the 2010 census, New England collectively has 33 electoral votes.

The following table presents the vote percentage for the popular-vote winner for each New England state, New England as a whole, and the United States as a whole, in each presidential election from 1900 to 2016, with the vote percentage for the Republican candidate shaded in red and the vote percentage for the Democratic candidate shaded in blue:

| Year | Connecticut | Maine | Massachusetts | New Hampshire | Rhode Island | Vermont | New England | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 54.0% | 48.0% | 61.0% | 47.6% | 54.9% | 61.1% | 55.6% | 48.2% |

| 2012 | 58.1% | 56.3% | 60.7% | 52.0% | 62.7% | 66.6% | 59.1% | 51.1% |

| 2008 | 60.6% | 57.7% | 61.8% | 54.1% | 62.9% | 67.5% | 60.6% | 52.9% |

| 2004 | 54.3% | 53.6% | 61.9% | 50.2% | 59.4% | 58.9% | 57.7% | 50.7% |

| 2000 | 55.9% | 49.1% | 59.8% | 48.1% | 61.0% | 50.6% | 56.1% | 48.4% |

| 1996 | 52.8% | 51.6% | 61.5% | 49.3% | 59.7% | 53.4% | 56.8% | 49.2% |

| 1992 | 42.2% | 38.8% | 47.5% | 38.9% | 47.0% | 46.1% | 44.4% | 43.0% |

| 1988 | 52.0% | 55.3% | 53.2% | 62.5% | 55.6% | 51.1% | 49.5% | 53.4% |

| 1984 | 60.7% | 60.8% | 51.2% | 68.7% | 51.7% | 57.9% | 56.2% | 58.8% |

| 1980 | 48.2% | 45.6% | 41.9% | 57.7% | 47.7% | 44.4% | 44.7% | 50.8% |

| 1976 | 52.1% | 48.9% | 56.1% | 54.7% | 55.4% | 54.3% | 51.7% | 50.1% |

| 1972 | 58.6% | 61.5% | 54.2% | 64.0% | 53.0% | 62.7% | 52.5% | 60.7% |

| 1968 | 49.5% | 55.3% | 63.0% | 52.1% | 64.0% | 52.8% | 56.1% | 43.4% |

| 1964 | 67.8% | 68.8% | 76.2% | 63.9% | 80.9% | 66.3% | 72.8% | 61.1% |

| 1960 | 53.7% | 57.0% | 60.2% | 53.4% | 63.6% | 58.6% | 56.0% | 49.7% |

| 1956 | 63.7% | 70.9% | 59.3% | 66.1% | 58.3% | 72.2% | 62.0% | 57.4% |

| 1952 | 55.7% | 66.0% | 54.2% | 60.9% | 50.9% | 71.5% | 56.1% | 55.2% |

| 1948 | 49.5% | 56.7% | 54.7% | 52.4% | 57.6% | 61.5% | 51.5% | 49.6% |

| 1944 | 52.3% | 52.4% | 52.8% | 52.1% | 58.6% | 57.1% | 52.4% | 53.4% |

| 1940 | 53.4% | 51.1% | 53.1% | 53.2% | 56.7% | 54.8% | 52.8% | 54.7% |

| 1936 | 55.3% | 55.5% | 51.2% | 49.7% | 53.1% | 56.4% | 50.9% | 60.8% |

| 1932 | 48.5% | 55.8% | 50.6% | 50.4% | 55.1% | 57.7% | 49.1% | 57.4% |

| 1928 | 53.6% | 68.6% | 50.2% | 58.7% | 50.2% | 66.9% | 53.2% | 58.2% |

| 1924 | 61.5% | 72.0% | 62.3% | 59.8% | 59.6% | 78.2% | 63.3% | 54.0% |

| 1920 | 62.7% | 68.9% | 68.5% | 59.8% | 64.0% | 75.8% | 66.7% | 60.3% |

| 1916 | 49.8% | 51.0% | 50.5% | 49.1% | 51.1% | 62.4% | 51.1% | 49.2% |

| 1912 | 39.2% | 39.4% | 35.5% | 39.5% | 39.0% | 37.1% | 36.6% | 41.8% |

| 1908 | 59.4% | 63.0% | 58.2% | 59.3% | 60.8% | 75.1% | 60.2% | 51.6% |

| 1904 | 58.1% | 67.4% | 57.9% | 60.1% | 60.6% | 78.0% | 60.4% | 56.4% |

| 1900 | 56.9% | 61.9% | 57.6% | 59.3% | 59.7% | 75.7% | 59.4% | 51.6% |

Political party strength

Judging purely by party registration rather than voting patterns, New England today is one of the most Democratic regions in the U.S.[112][113][114] According to Gallup, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont are "solidly Democratic", Maine "leans Democratic", and New Hampshire is a swing state.[115] Though New England is today considered a Democratic Party stronghold, much of the region was staunchly Republican before the mid-twentieth century. This changed in the late 20th century, in large part due to demographic shifts[116] and the Republican Party's adoption of socially conservative platforms as part of their strategic shift towards the South.[59] For example, Vermont voted Republican in every presidential election but one from 1856 through 1988, and has voted Democratic every election since. Maine and Vermont were the only two states in the nation to vote against Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt all four times he ran for president. Republicans in New England are today considered by both liberals and conservatives to be more moderate (socially liberal) compared to Republicans in other parts of the U.S.[117]

- † Elected as an independent, but caucuses with the Democratic Party.

| State | Governor | Senior U.S. Senator | Junior U.S. Senator | U.S. House Delegation | Upper House Majority | Lower House Majority |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | D. Malloy | R. Blumenthal | C. Murphy | Democratic 5–0 | Tied 18–18 | Democratic 80–71 |

| ME | P. LePage | S. Collins | A. King[†] | Split 1–1 | Republican 18–17 | Democratic 76–72–2 |

| MA | C. Baker | E. Warren | E. Markey | Democratic 9–0 | Democratic 34–6 | Democratic 125–35 |

| NH | C. Sununu | J. Shaheen | M. Hassan | Democratic 2-0 | Republican 14–10 | Republican 226–174 |

| RI | G. Raimondo | J. Reed | S. Whitehouse | Democratic 2–0 | Democratic 33–5 | Democratic 64–10–1 |

| VT | P. Scott | P. Leahy | B. Sanders[†] | Democratic 1–0 | Democratic 21–7–2 | Democratic 83–53–7–7 |

New Hampshire primary

Historically, the New Hampshire primary has been the first in a series of nationwide political party primary elections held in the United States every four years. Held in the state of New Hampshire, it usually marks the beginning of the U.S. presidential election process. Even though few delegates are chosen from New Hampshire, the primary has always been pivotal to both New England and American politics. One college in particular, Saint Anselm College, has been home to numerous national presidential debates and visits by candidates to its campus.[118]

Education

Colleges and universities

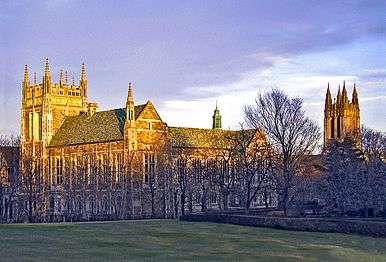

New England contains some of the oldest and most renowned institutions of higher learning in the United States and the world. Harvard College was the first such institution, founded in 1636 at Cambridge, Massachusetts to train preachers. Yale University was founded in Saybrook, Connecticut in 1701, and awarded the nation's first doctoral (PhD) degree in 1861. Yale moved to New Haven, Connecticut in 1718, where it has remained to the present day.

Brown University was the first college in the nation to accept students of all religious affiliations, and is the seventh oldest U.S. institution of higher learning. It was founded in Providence, Rhode Island in 1764. Dartmouth College was founded five years later in Hanover, New Hampshire with the mission of educating the local American Indian population as well as English youth. The University of Vermont, the fifth oldest university in New England, was founded in 1791, the same year that Vermont joined the Union.

In addition to four out of eight Ivy League schools, New England contains the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), four of the original Seven Sisters, the bulk of educational institutions that are identified as the "Little Ivies", one of the eight original Public Ivies, the Colleges of Worcester Consortium in central Massachusetts, and the Five Colleges consortium in western Massachusetts. The University of Maine, the University of New Hampshire, the University of Connecticut, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, the University of Rhode Island, and the University of Vermont are the flagship state universities in the region.

Private and independent secondary schools

At the pre-college level, New England is home to a number of American independent schools (also known as private schools). The concept of the elite "New England prep school" (preparatory school) and the "preppy" lifestyle is an iconic part of the region's image.[119]

- See the list of private schools for each state:

Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont.

Public education

New England is home to some of the oldest public schools in the nation. Boston Latin School is the oldest public school in America and was attended by several signatories of the Declaration of Independence.[120] Hartford Public High School is the second oldest operating high school in the U.S.[121]

As of 2005, the National Education Association ranked Connecticut as having the highest-paid teachers in the country. Massachusetts and Rhode Island ranked eighth and ninth, respectively.

New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have cooperated in developing a New England Common Assessment Program test under the No Child Left Behind guidelines. These states can compare the resultant scores with each other.

The Maine Learning Technology Initiative program supplies all students with Apple MacBook laptops.

Academic journals and press

There are several academic journals and publishing companies in the region, including The New England Journal of Medicine, Harvard University Press, and Yale University Press. Some of its institutions lead the open access alternative to conventional academic publication, including MIT, the University of Connecticut, and the University of Maine. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston publishes the New England Economic Review.[122]

Culture

New England has a shared heritage and culture primarily shaped by waves of immigration from Europe.[123] In contrast to other American regions, many of New England's earliest Puritan settlers came from eastern England, contributing to New England's distinctive accents, foods, customs, and social structures.[124]:30–50 Within modern New England a cultural divide exists between urban New Englanders living along the densely populated coastline, and rural New Englanders in western Massachusetts, northwestern and northeastern Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, where population density is low.[125]

Today, New England is the least religious region of the U.S. In 2009, less than half of those polled in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont claimed that religion was an important part of their daily lives. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, also among the ten least religious states, 55 and 53%, respectively, of those polled claimed that it was.[126] According to the American Religious Identification Survey, 34% of Vermonters, a plurality, claimed to have no religion; on average, nearly one out of every four New Englanders identifies as having no religion, more than in any other part of the U.S.[127] New England had one of the highest percentages of Catholics in the U.S. This number declined from 50% in 1990 to 36% in 2008.[127]

Cultural roots

Many of the first European colonists of New England had a maritime orientation toward whaling (first noted about 1650)[128] and fishing, in addition to farming. New England has developed a distinct cuisine, dialect, architecture, and government. New England cuisine has a reputation for its emphasis on seafood and dairy; clam chowder, lobster, and other products of the sea are among some of the region's most popular foods.

New England has largely preserved its regional character, especially in its historic places. The region has become more ethnically diverse, having seen waves of immigration from Ireland, Quebec, Italy, Portugal, Poland, Asia, Latin America, Africa, other parts of the U.S., and elsewhere. The enduring European influence can be seen in the region in the use of traffic rotaries, the bilingual French and English towns of northern Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire, the region's heavy prevalence of English town- and county-names, and its unique, often non-rhotic coastal dialect reminiscent of southeastern England.

Within New England, many names of towns (and a few counties) repeat from state to state, primarily due to settlers throughout the region having named their new towns after their old ones. For example, the town of North Yarmouth, Maine was named by settlers from Yarmouth, Massachusetts, which was in turn named for Great Yarmouth in England. As another example, every New England state has a town named Warren, and every state except Rhode Island has a city or town named Andover, Bridgewater, Chester, Franklin, Manchester, Plymouth, Washington, and Windsor; in addition, every state except Connecticut has a Lincoln and a Richmond, and Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine each contains a Franklin County.

Accents

There are several American English accents spoken in the region, including New England English and its derivative known as the Boston accent.

The so-called Boston accent is native to the northeastern coastal regions of New England. Many of its most identifiable features are believed to have originated from the influence of England's Received Pronunciation, which shares those features, such as dropping final R and the broad A. Another source was 17th century speech in East Anglia and Lincolnshire where many of the Puritan immigrants originated. The East Anglian "whine" developed into the Yankee "twang".[124] Boston accents were most strongly associated at one point with the so-called "Eastern Establishment" and Boston's upper class, although today the accent is predominantly associated with blue-collar natives, as exemplified by movies such as Good Will Hunting and The Departed. The Boston accent and those accents closely related to it cover eastern Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine.[129]

Some Rhode Islanders speak with a non-rhotic accent that many compare to a "Brooklyn" accent or a cross between a New York and Boston accent, where "water" becomes "wata". Many Rhode Islanders distinguish the aw sound [ɔː], as one might hear in New Jersey; e.g., the word "coffee" is pronounced /ˈkɔːfi/ KAW-fee.[130] This type of accent was brought to the region by early settlers from eastern England in the Puritan migration in the mid-seventeenth century.[124]:13–207

Social activities and music

Acadian and Québécois culture are included in music and dance in much of rural New England, particularly Maine. Contra dancing and country square dancing are popular throughout New England, usually backed by live Irish, Acadian, or other folk music. Fife and drum corps are common, especially in southern New England and more specifically Connecticut, with music of mostly Celtic, English, and local origin.

Traditional knitting, quilting, and rug hooking circles in rural New England have become less common; church, sports, and town government are more typical social activities. These traditional gatherings are often hosted in individual homes or civic centers.

New England leads the U.S. in ice cream consumption per capita.[131][132] In the U.S., candlepin bowling is essentially confined to New England, where it was invented in the 19th century.[133]

New England was an important center of American classical music for some time. Prominent modernist composers also come from the region, including Charles Ives and John Adams. Boston is the site of the New England Conservatory and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

In popular music, the region has produced Donna Summer, JoJo, New Edition, Bobby Brown, Passion Pit, Meghan Trainor, New Kids on the Block, Rachel Platten, and John Mayer. In rock music, the region has produced Rob Zombie, Aerosmith, The Modern Lovers, Phish, the Pixies, GG Allin, the Dropkick Murphys, and Boston. Quincy, Massachusetts native Dick Dale helped popularize surf rock.

Media

The leading U.S. cable TV sports broadcaster ESPN is headquartered in Bristol, Connecticut. New England has several regional cable networks, including New England Cable News (NECN) and the New England Sports Network (NESN). New England Cable News is the largest regional 24-hour cable news network in the U.S., broadcasting to more than 3.2 million homes in all of the New England states. Its studios are located in Newton, Massachusetts, outside of Boston, and it maintains bureaus in Manchester, New Hampshire; Hartford, Connecticut; Worcester, Massachusetts; Portland, Maine; and Burlington, Vermont.[134] In Connecticut, Litchfield, Fairfield, and New Haven counties it also broadcasts New York based news programs—this is due in part to the immense influence New York has on this region's economy and culture, and also to give Connecticut broadcasters the ability to compete with overlapping media coverage from New York-area broadcasters.

NESN broadcasts the Boston Red Sox baseball and Boston Bruins hockey throughout the region, save for Fairfield County, Connecticut.[135] Most of Connecticut, save for Windham county in the state's northeast corner, and even southern Rhode Island, receives the YES Network, which broadcasts the games of the New York Yankees. For the most part, the same areas also carry SportsNet New York (SNY), which broadcasts New York Mets games.

Comcast SportsNet New England broadcasts the games of the Boston Celtics, New England Revolution and Boston Cannons.

While most New England cities have daily newspapers, The Boston Globe and The New York Times are distributed widely throughout the region. Major newspapers also include The Providence Journal, Portland Press Herald, and Hartford Courant, the oldest continuously published newspaper in the U.S.[136]

Comedy

New Englanders are well represented in American comedy. Writers for The Simpsons and late-night television programs often come by way of the Harvard Lampoon. Family Guy is an animated sitcom situated in Rhode Island, created by Connecticut native and Rhode Island School of Design graduate Seth MacFarlane (along with American Dad! and The Cleveland Show). A number of Saturday Night Live (SNL) cast members have roots in New England, from Adam Sandler to Amy Poehler, who also stars in the NBC television series Parks and Recreation. Former Daily Show correspondents Rob Corddry and Steve Carell are from Massachusetts. Carell was also involved in film and the American adaptation of The Office, which features Dunder-Mifflin branches set in Stamford, Connecticut and Nashua, New Hampshire.

Late-night television hosts Jay Leno and Conan O'Brien have roots in the Boston area. Notable stand-up comedians are also from the region, including Bill Burr, Dane Cook, Steve Sweeney, Steven Wright, Sarah Silverman, Lisa Lampanelli, Denis Leary, Lenny Clarke, Patrice O'Neal, and Louis CK. SNL cast member Seth Meyers once attributed the region's imprint on American humor to its "sort of wry New England sense of pointing out anyone who's trying to make a big deal of himself", with the Boston Globe suggesting that irony and sarcasm are its trademarks, as well as Irish influences.[137]

Literature

The literature of New England has had an enduring influence on American literature in general, with themes that are emblematic of the larger concerns of American letters, such as religion, race, the individual versus society, social repression, and nature.[138] Famous New England writers include Transcendentalist philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, poets Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth Bishop, and novelists Nathaniel Hawthorne and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Boston was the center of the American publishing industry for some years, largely on the strength of its local writers and before it was overtaken by New York in the middle of the nineteenth century. Boston remains the home of publishers Houghton Mifflin and Pearson Education, and it was the longtime home of literary magazine The Atlantic Monthly. Merriam-Webster is based in Springfield, Massachusetts. Yankee is a magazine for New Englanders based in Dublin, New Hampshire.

Twentieth and twenty-first century writers hailing from New England include Maine native Stephen King and New Hampshire native John Irving, and New England is a major setting of their works. George V. Higgins wrote about life in the New England criminal underworld, while H.P. Lovecraft set many of his works of horror in his native Rhode Island.

Film, television, and acting

New England has a rich history in filmmaking dating back to the dawn of the motion picture era at the turn of the 20th century, sometimes dubbed Hollywood East by film critics. A theater at 547 Washington Street in Boston was the second location to debut a picture projected by the Vitascope, and shortly thereafter several novels were being adapted for the screen and set in New England, including The Scarlet Letter and The House of Seven Gables.[139] The New England region continued to churn out films at a pace above the national average for the duration of the 20th century, including blockbuster hits such as Jaws, Good Will Hunting, and The Departed, all of which won Oscars. The New England area became known for a number of themes that recurred in films made during this era, including the development of yankee characters, smalltown life contrasted with city values, seafaring tales, family secrets, and haunted New England.[140] These themes are rooted in centuries of New England culture and are complemented by the region's diverse natural landscape and architecture, from the Atlantic Ocean and brilliant fall foliage to church steeples and skyscrapers.

Since the turn of the millennium, Boston and the greater New England region have been home to the production of numerous films and television series, thanks in part to tax incentive programs put in place by local governments to attract filmmakers to the region.[141]

Notable actors and actresses that have come from the New England area include Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Amy Poehler, Elizabeth Banks, Steve Carell, Ruth Gordon, John Krasinski, Edward Norton, Mark Wahlberg, and Matthew Perry. A full list of those from Massachusetts can be found here, and a listing of notable films and television series produced in the area here.

Sports

Two popular American sports were invented in New England: basketball, invented by James Naismith (a Canadian) in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1891,[142] and volleyball, invented in 1895 by William G. Morgan, in Holyoke, Massachusetts.[143] Additionally, Walter Camp is credited with developing modern American football in New Haven, Connecticut, in the 1870s and 1880s.[144]

New Hampshire Motor Speedway is an oval racetrack that has hosted several NASCAR and American Championship Car Racing races, whereas Lime Rock Park in Connecticut is a traditional road racing venue home of sports car races. Events at these venues have had the "New England" moniker, such as the NASCAR New England 300 and New England 200, the IndyCar Series New England Indy 200, and the American Le Mans Series New England Grand Prix.

Professional and semi-professional sports teams

The major professional sports teams in New England are based in Massachusetts: the Boston Red Sox, the New England Patriots (based in Foxborough, Massachusetts), the Boston Celtics, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution (also based in Foxborough), the Boston Breakers, and the Boston Cannons. Hartford had a professional hockey team, the Hartford Whalers, from 1975 until they moved to North Carolina in 1997. A WNBA team, the Connecticut Sun, are based in southeastern Connecticut at the Mohegan Sun resort, which is also home to the professional indoor lacrosse team the New England Black Wolves. New England is also home to the Boston Blades, Boston Pride and the Connecticut Whale, which represent three of the five professional women's hockey teams in the United States.

There are also minor league baseball and hockey teams based in larger cities such as the Bridgeport Bluefish (baseball), the Bridgeport Sound Tigers (hockey), the Connecticut Tigers (baseball), the Hartford Yard Goats (baseball), the Hartford Wolf Pack (hockey), the Lowell Spinners (baseball), the Manchester Monarchs (hockey), the New Britain Bees (baseball), the New Hampshire Fisher Cats (baseball), the Pawtucket Red Sox (baseball), the Portland Sea Dogs (baseball), the Providence Bruins (hockey), the Springfield Thunderbirds (hockey), the Vermont Lake Monsters (baseball), and the Worcester Railers (hockey).

The NBA G League fields a team in New England: the Maine Red Claws, based in Portland, Maine. The Springfield Armor in Springfield, Massachusetts, previously played in the region. The Red Claws are affiliated with the Boston Celtics and the Armor were affiliated with the Brooklyn Nets, prior to relocating to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to become the Grand Rapids Drive. New England is also represented in the Premier Basketball League by the Vermont Frost Heaves of Barre, Vermont.

Thanksgiving Day high school football rivalries date back to the 19th century, and the Harvard-Yale rivalry ("The Game") is the oldest active rivalry in college football. The Boston Marathon, run on Patriots' Day every year, is a New England cultural institution and the oldest annual marathon in the world. While the race offers far less prize money than many other marathons, the race's difficulty and long history make it one of the world's most prestigious marathons.[145]

Transportation

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) provides rail and subway service within the Boston metropolitan area, bus service in Greater Boston, and commuter rail service throughout Eastern Massachusetts and parts of Rhode Island. The New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority in partnership with the Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) operates the Metro-North Railroad, which provides commuter rail service in Southwestern Connecticut in the corridor between New York City and New Haven. CTDOT provides the Shore Line East commuter rail service along the Connecticut coastline east of New Haven, terminating in Old Saybrook and New London.

Amtrak provides interstate rail service throughout New England. Boston is the northern terminus of the Northeast Corridor. The Vermonter connects Vermont to Massachusetts and Connecticut, while the Downeaster links Maine to Boston. The long-distance Lake Shore Limited train has two eastern termini after splitting in Albany, one of which is Boston. This provides rail service on the former Boston and Albany Railroad, which runs between its namesake cities. The rest of the Lake Shore Limited continues to New York City.

See also

- Autumn in New England

- Brother Jonathan

- Extreme points of New England

- Fieldstone

- Historic New England

- List of amusement parks in New England

- List of beaches in New England

- List of mammals of New England

- Manor of East Greenwich

- New Albion

- New Albion (colony)

- New England/Acadian forests

- New England Confederation

- New England Planters

- New England Summer Nationals

- Northeastern coastal forests

- Southeastern New England AVA wine region

- Swamp Yankee

Notes

References

- ↑ "Resident Population in the New England Census Division". US Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Yankee". The American Heritage Dictionary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Gross domestic product (GDP) by state (millions of current dollars)". U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- 1 2 "Britannica article". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ↑ "American Heritage Dictionary". Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Random House Unabridged Dictionary". Dictionary.infoplease.com. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. August 13, 2010. Retrieved October 16, 2010.

- ↑ "New England". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2003. Archived November 1, 2003, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The 1692 Salem Witch Trials". SalemWitchTrialsMuseum.com. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ↑ Chiu, Monica (2009). Asian Americans in New England: Culture and Community. Lebanon, NH: University of New Hampshire Press. p. 44. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Bain, Angela Goebel; Manring, Lynne; and Mathews, Barbara. Native Peoples in New England. Retrieved July 21, 2010, from Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

- ↑ "Abenaki History". abenakination.org. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Allen, William (1849). The History of Norridgewock. Norridgewock ME: Edward J. Peet. p. 10. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Wiseman, Fred M. "The Voice of the Dawn: An Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation". p. 70. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ "What are the oldest cities in America?". Glo-con.com. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- ↑ Cressy, David (1987). Coming Over: Migration and Communication Between England and New England in the Seventeenth Century. p. 4. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Swindler, William F., ed; Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions 10 Volumes; Dobbs Ferry, New York; Oceana Publications, 1973–1979. Volume 5: pp. 16–26.

- ↑ "...joint stock company organized in 1620 by a charter from the British crown with authority to colonize and govern the area now known as New England." New England, Council for. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 13, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service: Britannica.com Archived February 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Haxtun, Anne Arnoux (1896). Signers of the Mayflower Compact, vol. 1. New York: The Mail and Express Publishing Company. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ Townsend, Edward Waterman (1906). Our Constitution: How and Why It Was Made. New York: Moffat, Yard & Company. p. 42. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. "Public Records: The History of the Arms and Great Seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts". sec.state.ma.us. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ↑ Northend, William Dummer (1896). The Bay Colony: A Civil, Religious and Social History of the Massachusetts Colony. Boston: Estes and Lauriat. p. 305.

- ↑ "History of Boston, Massachusetts". U-S-History.com. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ↑ State of Connecticut. "About Connecticut". CT.gov. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Peace, Nancy E. (November 1976). "Roger Williams—A Historiographical Essay" (PDF). Rhode Island History. Providence RI: The Rhode Island Historical Society. pp. 103–115. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ "History & Famous Rhode Islanders". Rhode Island Tourism Division. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Hall, Hiland (1868). The History of Vermont: From Its Discovery to Its Admission into the Union. Albany NY: Joel Munsell. p. 3.

- ↑ "1637 - The Pequot War". The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ↑ Howe, Daniel Wait (1899). The Puritan Republic of the Massachusetts Bay in New England. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill. pp. 308–311.

- ↑ "1675 - King Philip's War". The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 112. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

- ↑ Martucci, David B. "The New England Flag". D. Martucci. Archived from the original on April 1, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Flags of the Early North American Colonies and Explorers". Historical Flags of Our Ancestors.

- ↑ Leepson, Marc (2007). Flag: An American Biography. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. p. 14.

- ↑ Various (1908). Proceedings of the First New England Conference: Called by the Governors of the New England States, Boston, Nov. 23, 24, 1908. Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Company. p. 6.

- ↑ Preble, George Henry (1880). History of the Flag of the United States of America: And of the Naval and Yacht-club Signals, Seals, and Arms, and Principal National Songs of the United States, with a Chronicle of the Symbols, Standards, Banners, and Flags of Ancient and Modern Nations. Boston: A. Williams. p. 190.

- ↑ Stark, Bruce P. "The Dominion of New England". Connecticut Humanities Council. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ Palfrey, John Gorham (1865). History of New England, vol. 3. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 561–590. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ Palfrey, John Gorham (1873). A Compendious History of New England, vol. 3. Boston: H.C. Shepard. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ Wesley Frank Craven, Colonies in Transition, 1660 – 1713 (1968). p. 224.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Slavery in New Hampshire". Slavenorth.com. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Yankeeland". The Random House Dictionary. Boston: Random House. 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ↑ Library of Congress. "Missouri Compromise: Primary Documents of American History". Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ James Schouler, History of the United States, Vol. 1 (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. 1891; copyright expired)

- ↑ Dwight, Theodore (1833). History of the Hartford Convention. New York: N. & J. White. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. University of Illinois Press. p. 233.

- ↑ Cooper, Thomas Valentine; Fenton, Hector Tyndale (1884). American Politics (Non-Partisan) from the Beginning to Date, Book III. Chicago: C. R. Brodix. pp. 64–69.

- ↑ Cairns, William B. (1912). A History of American Literature. New York: Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ↑ "New England", Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived October 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "History & Culture: Birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution". Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor, MA, RI. National Park Service. June 11, 2009. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Bagnall, William R. The Textile Industries of the United States: Including Sketches and Notices of Cotton, Woolen, Silk, and Linen Manufacturers in the Colonial Period. Vol. I. pg. 97. The Riverside Press, 1893.

- ↑ "Forging Arms for the Nation". Springfield Armory National Historic Site, Massachusetts. National Park Service. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Coen, Scott (May 13, 2011). "The Springfield Armory: The Heartbeat of the 19th Century Industrial Revolution". MassLive.com. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Rooker, Sarah. "The Industrial Revolution: Connecticut River Valley Overview". Teaching the Industrial Revolution. The Flow of History. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Dublin, Thomas. "Lowell Millhands". Transforming Women's Work (1994) pp. 77–118.

- 1 2 "Census Data for Year 1850". Historical Census Browser. University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. "American Abolitionism and Religion". Divining America: Religion in American History. National Humanities Center TeacherServe. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- 1 2 Tarr, David; Benenson, Bon (2012). Elections A to Z. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press. p. 542. ISBN 978-0-87289-769-4. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ↑ Minchin, Timothy J. (2013). "The Crompton Closing: Imports and the Decline of America's Oldest Textile Company". Journal of American Studies. 47 (1): 231–260.

- ↑ Henry Etzkowitz, MIT and the Rise of Entrepreneurial Science (Routledge 2007)

- ↑ David Koistinen, Confronting Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England (2013)

- ↑ Bishaw, Alemayehu; Iceland, John (May 2003). "Poverty: 1999" (PDF). Census 2000 Brief. US Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2014 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars): 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (S1901)". American Factfinder. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Part 1: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). 2000 Census of Population and Housing – United States Summary: 2000. United States Census Bureau. April 2004. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "The British Isles and all that ...". Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Glacial Features of the Exotic Terrane". The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US. Paleontological Research Institution. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Emerson, Philip (1922). The Geography of New England. New York: The Macmillan Company. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Physiographic divisions of the conterminous U.S.". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Topography of the Appalachian/Piedmont Region 2". The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Earth Science of the Northeastern US. Paleontological Research Institution. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Shaw, Ethan. "The 10 Tallest Mountains East of the Mississippi". USA Today. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "World Record Wind". Mount Washington Observatory. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "World Record Wind Gust: 408 km/h". World Meteorological Organization. January 22, 2010. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ↑ "About Us". Mount Washington Observatory. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Hrin, Eric (March 26, 2011). "Wolfe turns love of books into career; One-hundredth anniversary of library in Troy approaching". The Daily Review. Towanda, PA. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ↑ "New England's Fall Foliage". Discover New England. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- 1 2 "New England Population: 2010 Census" (PDF). Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Population Estimates".

- ↑ Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (December 8, 2010). "Births: Final Data for 2008" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. 59 (1). Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- 1 2 "Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin: 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: New England Division (B03001)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "People Reporting Ancestry: 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: New England Division (B04006)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ Includes English and "British" but not Scottish or Welsh.

- 1 2 "Language Spoken at Home: 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: New England Division (S1601)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Language Spoken at Home by Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: New England Division (B16001)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations: 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: New England Division (S0501)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Place of Birth for the Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates: New England Division (B05006)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- 1 2 "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 - United States -- Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area: 2015 Population Estimates (GCT-PEPANNRES)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 - United States -- Combined Statistical Area: 2015 Population Estimates (GCT-PEPANNRES)". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ↑ "TIGERweb". U.S. Census Bureau. (Combined Statistical Areas checkbox). Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- 1 2 "Background on the New England Economy". U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on September 19, 2002.

- ↑ "Regional Data: GDP & Personal Income". Bureau of Economic Analysis. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ↑ Rich, Jack C. (1988). Materials and Methods of Sculpture. Dover Publications.

- ↑ "Maine State Agriculture Overview - 2004" (PDF). USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2006.

- ↑ "Vermont State Agriculture Overview - 2006" (PDF). USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2006.

- ↑ "Connecticut State Agriculture Overview - 2005" (PDF). USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Massachusetts State Agriculture Overview - 2005" (PDF). USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 10, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ↑ Hemmingway, Sam (July 20, 2008). "Nukes by the Numbers". Burlington Free Press.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Energy. "State Energy Profiles: State Rankings - State Ranking 7. Total Energy Consumed per Capita, 2013 (million Btu)". Retrieved April 4, 2016.