Nevile Henderson

| Sir Nevile Henderson GCMG | |

|---|---|

|

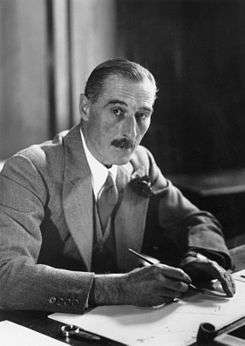

Ambassador Henderson in office, May 1937 | |

| Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia | |

|

In office 21 November 1929 – 1935 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Howard William Kennard |

| Succeeded by | Ronald Ian Campbell (1939) |

| Ambassador to Argentina | |

|

In office 1935–1937 | |

| Monarch |

George V (1935–36) Edward VIII (1936) George VI (1936–37) |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Henry Chilton |

| Succeeded by | Esmond Ovey |

| Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Germany | |

|

In office 28 May 1937 – 7 September 1939 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Eric Phipps[1] |

| Succeeded by | Brian Robertson (1949)[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

10 April 1882 Sedgwick, Sussex, England |

| Died |

30 December 1942 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

Sir Nevile Meyrick Henderson GCMG (10 June 1882 – 30 December 1942) was a British diplomat and Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Nazi Germany from 1937 to 1939.

Life and career

He was born at Sedgwick Park near Horsham, Sussex, the third child of Robert and Emma Henderson.[2]

He was educated at Eton and joined the Diplomatic Service in 1905. He served as an envoy to France in 1928/29 and as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between 1929 and 1935,[3] where he was in close confidence with King Alexander and Prince Paul. In 1935 he became Ambassador to Argentina before on 28 May 1937 he was appointed Ambassador in Berlin.

A believer in appeasement policies, Henderson thought Hitler could be controlled and pushed toward peace and cooperation with the Western powers. In February 1939, he cabled the FCO in London:

If we handle him (Hitler) right, my belief is that he will become gradually more pacific. But if we treat him as a pariah or mad dog we shall turn him finally and irrevocably into one.[4]

Henderson was ambassador at the time of the 1938 Munich Agreement, and counselled Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to enter into it. Shortly thereafter, he returned to London for medical treatment, returning to Berlin in ill-health in February 1939 (he would die of cancer less than four years later).[5]

After Wehrmacht troops on 15/16 March 1939 occupied the remaining territory of the Czechoslovak Republic in defiance of the Agreement, Chamberlain spoke of a betrayal of confidence and decided to withstand German aggression. Henderson handed over a protest note and was intermittently recalled to London. On the eve of World War II, Henderson came into frequent conflict with Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Undersecretary of the Foreign Office. Henderson argued that Britain should go about rearmament in secret, as a public rearmament would encourage the belief that Britain planned to go to war with Germany. Cadogan and the Foreign Office disagreed.

With the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939 and the Anglo-Polish military alliance two days later, war became imminent. On the night of 30 August, Henderson had an extremely tense meeting with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop presented the German "final offer" to Poland at midnight, and warned Henderson that if he received no reply by dawn, the "final offer" would be considered rejected. "When Ribbentrop refused to give a copy of the German demands to the British Ambassador at midnight of 30–31 August 1939, the two almost came to blows. Ambassador Henderson, who had long advocated concessions to Germany, recognised that here was a deliberately conceived alibi the German government had prepared for a war it was determined to start. No wonder Henderson was angry; von Ribbentrop on the other hand could see war ahead and went home beaming."[6]

While negotiating with the Polish ambassador Józef Lipski and advising accommodation over Germany's territorial ambitions – as he had during the Austrian Anschluss and the occupation of Czechoslovakia – the Nazis staged the Gleiwitz incident and the Invasion of Poland began on 1 September. It was Henderson who had to deliver Britain's final ultimatum on the morning of 3 September 1939 to Minister Ribbentrop, stating that if hostilities between Germany and Poland did not cease by 11 a.m. that day, a state of war would exist. Germany did not respond, and Prime Minister Chamberlain declared war at 11:15 a.m. Henderson and his staff were briefly interned by the Gestapo before finally returning to Britain on 7 September.

After returning to London, Henderson asked for another ambassadorship, but was denied. He wrote Failure of a Mission: Berlin 1937–1939, which was published in 1940, in which he spoke highly of some members of the Nazi regime, including Hermann Göring, but not von Ribbentrop. He had been on friendly terms with members of the Astors' Cliveden set, which also supported appeasement. Henderson wrote in his memoirs how eager Prince Paul had been to illustrate his military plans to counter Mussolini's projected assault on Dalmatia, when the main body of the Italian Army had been sent overseas.[7]

Death

He died on 30 December 1942 from cancer which he had been suffering from since 1938. He was staying at the Dorchester Hotel in London at the time. He never married.[8]

References

- 1 2 List of diplomats of the United Kingdom to Germany#Ambassadors Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary 3

- ↑ Appeasing Hitler: The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson, 1937–39, Peter Neville, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999, ISBN 978-0333739877 p. 1.

- ↑ "No. 33573". The London Gazette. 24 January 1930. p. 494.

- ↑ Appeasing Hitler. The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson. 1937–39. Peter Neville. Palgrave 2000.

- ↑ Appeasing Hitler: The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson, 1937–39, findarticles.com; accessed 2 October 2014.

- ↑ A World At Arms by Gerhard Weinberg, p. 43.

- ↑ Jukic, Ilija, The Fall of Yugoslavia, New York and London, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Peter Neville: ‘Henderson, Sir Nevile Meyrick (1882–1942)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011, accessed 1 Nov 2014

Primary sources

- Henderson, Sir Neville (1940). Failure of a Mission 1937-9.

- Henderson, Sir Neville (20 September 1939). "Final Report on the Circumstances Leading to the Termination of his Mission to Berlin". (Cmd 6115) Pamphlet.

- Secondary sources

- Gilbert, Martin (2014). The Second World War: A Complete History. RosettaBooks.

- Jukic, Ilija (1974). The Fall of Yugoslavia. New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- McDonogh, Frank (2010). Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the road to war. Manchester.

- Henderson, Sir Neville (25 March 1940). "War's First Memoirs". Life Magazine.

- Neville, Peter (2000). "Appeasing Hitler: The Diplomacy of Sir Nevile Henderson 1937–39". Studies in Diplomacy and International Relations. Palgrave.

- Neville, Peter (2004). Henderson, Sir Nevile Meyrick (1882–1942). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edn, Jan 2011 ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 Nov 2014.

- Gerhard Weinberg (2005). A World At Arms: Global History of World War II. Cambridge.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nevile Henderson. |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Howard William Kennard |

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1929–1935 |

Succeeded by Ronald Ian Campbell |

| Preceded by Eric Phipps |

Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador to the Third Reich 1937–1939 |

Succeeded by No representation until 1950 Ivone Kirkpatrick |