Neustadt (Weinstraße) Hauptbahnhof

| Through station | |

| |

| Location |

Bahnhofsplatz 6, Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Rhineland-Palatinate Germany |

| Coordinates | 49°21′00″N 8°08′26″E / 49.35°N 8.140556°ECoordinates: 49°21′00″N 8°08′26″E / 49.35°N 8.140556°E |

| Line(s) |

|

| Platforms | 6 |

| Other information | |

| Station code | 4454[1] |

| DS100 code | RN[2] |

| IBNR | 8000275 |

| Category | 2[1] |

| Website | www.bahnhof.de |

| History | |

| Opened | 11 June 1847 |

| Previous names | Neustadt a/d. Haardt |

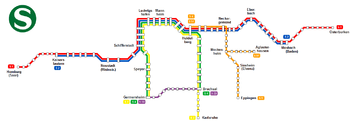

Neustadt (Weinstr) Hauptbahnhof – called Neustadt a/d. Haardt until 1935 and from 1945 until 1950[3] – is the central station of in the city of Neustadt in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. In addition to the Hauptbahnhof, Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn services stop at Neustadt (Weinstr) Böbig halt (Haltepunkt). Mußbach station and Neustadt (Weinstr) halt, opened on 19 November 2013, are also located in Neustadt.

The station was opened on 11 June 1847 as the terminus of the first section of the Palatine Ludwig Railway (Pfälzische Ludwigsbahn) from Rheinschanze (now: Ludwigshafen am Rhein) to Bexbach; this was opened over its full length two years later and now largely forms the Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway. With the opening of the Palatine Maximilian Railway (Pfälzischen Maximiliansbahn) to Wissembourg in 1855 and the Palatine Northern Railway (Pfälzische Nordbahn), built from 1865 to 1873, to Monsheim, it developed into a railway junction and also became a stop for long-distance trains. Since the 2000s, however, its importance for long-distance traffic has fallen. Since 2003, it has also been integrated into the network of the Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn. In addition, its entrance building is under heritage protection.[4]

Location

Neustadt Hauptbahnhof is centrally located within Neustadt. The inner city adjoins it to the north and the Saalbau, an events and conference centre, is nearby. To the south of the railway station is the Hambacher Höhe (Hambach heights). Crossing the line to the west of the station is the German Wine Route (Deutsche Weinstraße), which winds through this area through an S-shaped curve. Immediately east of the facilities serving passengers, the railway crosses a bridge over Landauer Straße, which also forms part of federal highway 39; Bahnhofstraße (railway street) branches off it and later rejoins it. To the east, past the freight yard, is the historical district of Branchweiler.

The station is located at line-kilometre 77.203. The zero point for the kilometrage is between Bexbach and Neunkirchen on the former Bavaria–Prussia national border.[5][6]

Railway lines

The Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway, which developed out of the Palatine Ludwig, comes from the northeast. It reaches Neustadt Hauptbahnhof over a drawn out S-curve, which takes it pass the freight facilities and Neustadt-Böbig halt. Beyond the Hauptbahnhof, it runs to the west or northwest along the Speyerbach through the Palatinate Forest (Pfälzerwald) towards Saarbrücken, passing the suburbs of Afrikaviertel and Schöntal.

The Maximilian Railway branches in the east from the line to Mannheim immediately after the crossing over federal road 39 and runs immediately along a long curve to the south towards Wissembourg. The Palatine Northern Railway starts in the northern station area and runs to the Neustadt-Böbig halt parallel with the line to Mannheim and continues via Bad Dürkheim and Grünstadt to Monsheim. The narrow gauge Palatine Overland Railway (Pfälzer Oberlandbahn), which existed between 1912 and 1955, began in the station forecourt (Bahnhofsvorplatz) and crossed the standard-gauge tracks a bridge it shared with the German Wine Route and passed through several wine-growing villages to Landau.

History

Connection to the rail network (1835–1849)

Originally it had been planned to build a railway running north-south in the then Bavarian Circle of the Rhine (Rheinkreis). However, it was agreed to first build a railway running east-west, which was to be used primarily for transporting coal from the Saar district (now part of the Saarland) to the Rhine. Two options were discussed for the general route through Kaiserslautern, as the development of a route through the Palatinate Forest (Pfälzerwald) proved to be complicated. At first the responsible engineers considered a route through the Dürkheim valley. However, this proved impractical because its side valleys were too low, and above all the climb to Frankenstein would have been too high steep. It would have required stationary steam engines and rope haulage to overcome the differences in altitude.[7] For this reason, they chose an option through the Neustadt valley, which would also be difficult to climb according to expert opinion, but would be feasible and, in contrast to the Dürkheim valley, would avoid the need for stationary steam engines.[8] At the same time, plans were also being made to build a railway line from Mainz to Neustadt, but these did not proceed.[9]

The tracks were laid between Rheinschanze and Neustadt from April 1846. Neustadt station’s entrance building was completed at the same time; this was built in the Italianate style. The section was finally opened on 11 June 1847. The opening train, which began in Ludwigshafen, was hauled by the locomotive Haardt, which was numbered 1.[10] The celebrations on site included music and cannon fire. On the platform were the state commissioner of Neustadt and some other subordinate officials; the president of the Palatinate region gave a speech. The return trip, in which these officials also took part, set off at 1 pm.[11]

The completion of the Neustadt–Frankenstein section was especially delayed by difficulties in acquiring the land needed and the difficult topography. For example, ten tunnels had to be built through hills and foothills.[12] The opening ceremony finally took place on 25 August 1849.[13]

Development of the Palatine Maximilian Railway (1849–1860)

.jpg)

At the same time as the Ludwig Railway was being built, plans were developed for a north-south link within the Palatinate. It was debated as to whether a route through the hills from Neustadt via Landau to Wissembourg (Alsace) or a route near the Rhine via Speyer, Germersheim and Wörth was more urgent and desirable. The military especially preferred a route on the edge of the Palatinate Forest. However, the political events of 1848 caused the project to come to a standstill.[14]

In January 1850, a brochure appeared in Neustadt (then called Neustadt an der Haardt) that promoted a route via Landau to Wissembourg (German: Weißenburg) and argued that the line should serve the larger townships rather than those immediately alongside the Rhine among other things. The decision finally went in favour of a line through the hills in 1852, after reports and investigations had been launched the previous year. On 3 November 1852, the Bavarian king, Maximilian II allowed its construction to proceed, by approving the creation of a joint-stock company that launched the project.[15]

The Neustadt–Landau was opened on 18 July 1855 and the Landau–Wissembourg section followed on 26 November 1855. This meant that Neustadt was the third railway junction within the Palatinate, after Schifferstadt (1847) and Ludwigshafen, formerly Rheinschanze (1853).

Origin of the Palatine Northern Railway (1860–1873)

.jpg)

In 1860, a local committee promoted the construction of a railway from Neustadt an der Weinstraße via Bad Dürkheim to Frankenthal. Above all, the factories in Dürkheim would benefit from a railway line. Although such a route would run parallel to the Palatine Maximilian Railway and the Mainz–Ludwigshafen railway, the proponents were optimistic that the planned route would be preferred due to its greater scenic appeal.[16]

The corresponding petition, however, met with no response since difficulties with the Palatine Ludwig Railway Company (Pfälzische Ludwigsbahn-Gesellschaft) were feared. For this reason, agreement was reached on 25 January 1862 that only a local railway would be built between Neustadt and Dürkheim.[17] The construction of the new railway line required major reconstruction measures, which cost 218,000 gulden. As a result of this project, the existing entrance building also had to be replaced, since the railway had gradually become congested and the station had to be extended. Neustadt was given a larger building, which was located somewhat further east and was equipped with a platform canopy.[18] In addition, the station received a goods shed as well as an engine shed with nine stalls. The tracks were extended to a total length of 1.8 kilometres and Landauer Straße, which had previously crossed the railway tracks on the level, was reconstructed through an underpass.[19]

The opening of the branch line to Dürkheim followed on 6 March 1865. It was extended to the Rhenish Hesse town of Monsheim on 20 July 1873 after the Grünstadt–Monsheim section had already been opened in March of the same year.

Further development (1873–1960)

In 1875, the station became the site of a state telegraph office.[20] In 1887, a curve was opened connecting the line from Schifferstadt towards the line to Neustadt (Maximilian Railway); this meant that freight trains from the east no longer had to reverse in the station.[21][22] The station received ticket gates on 15 October 1906.[23]

The station, together with the rest of the Palatinate rail network, became part of the Palatine Ludwig Railway Company (Pfälzische Ludwigsbahn-Gesellschaft) on 1 January 1909. From 16 December 1912 onwards, the so-called Palatine Overland Railway (Pfälzer Oberlandbahn) ran from the station forecourt as an interurban, first as far as Edenkoben and from 13 January 1913 to Landau. Its purpose was to link several places between Neustadt and Landau, which had not been connected to the Maximilian Railway. At the beginning of the First World War, a total of 401 trains passed through the station from 2 to 18 August.[24] 40 trains ran from Mannheim daily; 20 of them continued to Saarbrücken, the remaining ones ran on to the Maximilian Railway in Neustadt.[25] After Germany had lost the war and the French military had marched in, the Maximilian Railway south of Maikammer-Kirrweiler was blockaded for passenger traffic on 1 December 1918, but it was reopened three days later.[26]

The station was integrated into the newly founded Reichsbahndirektion Ludwigshafen (railway division of Ludwigshafen). During the dissolution of the railway division of Ludwigshafen on 1 April 1937, it was transferred to the railway division of Mainz.[27]

In the two world wars the station was hardly affected. After the Second World War, it became part of the Bundesbahndirektion Mainz (Deutsche Bundesbahn division of Mainz), which had succeeded the Reichsbahndirektion Mainz. In the 1950s, the Palatine Overland Railway was shut down. The railway station was redesigned and modernised in 1960.[19]

Developments since 1960

Since the main line from Mannheim had always had a great significance for long-distance traffic to Saarbrücken, it was gradually electrified, starting in 1960. The Saarbrücken–Homburg section could be operated electrically on 8 March 1960. The Homburg–Kaiserslautern followed on 18 May 1961 and from 12 March 1964 the entire line was electrically operated. The electrification of the last section was delayed mainly because of the numerous tunnels between Kaiserslautern and Neustadt that had to be enlarged. For the opening, a special service of the Rheingold ran along the route.[28]

The electrification work meant that this section was temporarily operated over only a single track and in one place trains could run at 40 km/h at most; as a result of the limited capacity several freight trains were directed over the Landau–Rohrbach railway and the Zeller Valley Railway (Zellertalbahn) towards Worms.[29]

On 1 August 1971, the station came under the jurisdiction of the railway division of Karlsruhe.[30] In 2003, the station was modernised, including the raising of the platform, in preparation for its integration in the Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn. Since then services on lines S1 (Homburg–Osterburken and S2 (Kaiserslautern–Mosbach) stop at the station.

The signalling technology within the station was also subsequently modernised. With the installation of the new electronic interlocking on 23 March 1998, the wye, which had allowed a bypass around the station since 1887, lost its eastern leg; since then, trains can no longer run directly towards Ludwigshafen, but instead they have to reverse in the station.[31] In addition, an additional electronic interlocking of the Alcatel El L90 type[32] has gradually taken over the regional railway network of the Palatinate and neighboring Rhinehesse since the 2000s. For example, Landau Hauptbahnhof as well as the stations of Edenkoben and Godramstein came under the control of the Neustadt electronic interlocking and Winden station was added one year later.[33]

Infrastructure

Entrance building

The monument-protected entrance building, which was completed in 1866, together with its annexes, is built in the Neoclassical style in sections that are two and a half or three storeys high. It has a mansard roof and a façade, which can be classified stylistically as Renaissance Revival.[4]

Reiterstellwerk

In the eastern part of the station there has been a signal box since 1920 that was built with a decoration in the Heimatstil ("home style") that has the appearance of equestrian headwear. It was designed by the Reichsbahn architect Grunwald and it is now heritage listed.[4] A dispatcher and two assistants were employed in it, but it was closed by the end of the millennium.[34]

Platforms and tracks

The three platforms of the main station are located on five through tracks and one dead-end track. Tracks 1, 2, 3 and 4 are used by trains of the Mannheim–Saarbrücken route and track 5 is used by trains that run on the Maximilian Railway. Track 1a is a dead-end track, which is used for Palatine Northern Railway services.

| Track | Usable length | Height | Current use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 216/50 m | 76/38 cm | S-Bahn services on the Osterburken–Homburg (Saar) route |

| 2 | 388/47 m | 76/38 cm | Trains on the Mannheim–Saarbrücken route |

| 3 | 388/47 m | 76/38 cm | Trains on the Saarbrücken–Mannheim route |

| 4 | 286/24 m | 76/38 cm | S-Bahn services on the (Saar)–Osterburken route |

| 5 | 286/24 m | 76/38 cm | Regionalbahn and Regional-Express services to Karlsruhe and Wissembourg |

| 1a | 125 m | 76 cm | Regionalbahn services to Freinsheim and Grünstadt |

Neustadt (Weinstr) Böbig halt

The halt (Haltepunkt) of Neustadt (Weinstr) Böbig is, in addition to the platforms described above, another stop within the precincts of Neustädter Hauptbahnhof. This consists of two platforms with three platform tracks and is located on the Mannheim–Saarbrücken and the Neustadt (Weinstr)–Monsheim railways.

When in 1969, the "school centre" of Böbig was built on the northeast edge of Neustadt not far from the junction of the Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway and the Palatine Northern Railway, the buses running there could hardly cope with the student traffic. On the initiative of the then teacher and later VRN official, Werner Schreiner, the Neustadt-Böbig halt was opened in 1974. This station allowed a large part of the student transport to be transferred from buses to rail.[35] Since 1995, it has been expanded, modernised and the platform has been raised. It has been served since 2003 by trains of the Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn, both those on line S1 (Homburg–Osterburken) and line S2 (Kaiserslautern–Mosbach).

| Track | Usable length | Height | Current use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 216/50 m | 76/38 cm | S-Bahn services on the Mannheim–Kaiserslautern–Homburg route and Regionalbahn services on the Neustadt–Freinsheim–Grünstadt route |

| 2 | 216/50 m | 76/38 cm | S-Bahn services on the Homburg–Kaiserslautern–Mannheim route |

| 3 | 216/50 m | 76/38 cm | Avoiding track for trains on the Saarbrücken–Mannheim route |

Locomotive depot and railway museum

A locomotive shed with a total length of 80 metres, a turntable and a two-storey building, which functioned as a workshop and office, were opened with the commissioning of the Palatine Ludwig Railway between Ludwigshafen and Neustadt on 11 June 1847.[36] It became an independent operating branch in 1869.[37] It was closed bit by bit around 1960 during the electrification of the Mannheim–Saarbrücken railway.

The locomotive shed from the construction period of the Ludwigsbahn now houses the DGEG-Eisenbahnmuseum Neustadt/Weinstraße, which in the meantime has also taken over the newer locomotive sheds to provide more storage areas.

Operations

Long distance services

Already in 1853, there were through passenger trains of the Mainz–Paris route. In 1854 there were three pairs of trains per day between the two cities; a trip between Mainz and Paris lasted around 17 hours.[38] With the completion of the Nahe Valley Railway, which was opened in stages by the Rhine-Nahe Railway Company (Rhein-Nahe Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft). In 1860, this connection was lost as the trains to Paris no longer ran through Neunkirchen.[39]

After the completion of the Alsenz Valley Railway, the station also developed into a major intercity hub, giving the city an international reputation.[40] From 1880, long-distance traffic increased significantly and extended to the Netherlands.[41] A direct connection from Ludwigshafen to Alsace had emerged in 1876 in the form of the Schifferstadt–Wörth and Wörth–Strasbourg lines, but, because they were single-track, most of the long-distance trains from Frankfurt went via the Maximilian Railway and therefore always had to reverse in Neustadt with the locomotive running around. Some coaches were coupled there with coaches from the Alsenz Valley Railway, while the other part of the train continued westwards over the Ludwig Railway.

After the First World War, the north-south traffic lost importance, as a result of which the station became more and more important for east-west traffic. From the 1990s, the station was served by InterRegio services before this type of service was abandoned a decade later. In 1993, Deutsche Bundesbahn had plans to run all Intercity and EuroCity services through Neustadt without stopping. However, it was persuaded to drop this idea.[42] Nevertheless, the Neustadt Hauptbahnhof lost its importance for long-distance traffic, so now it is served by only a few services.

| Line | Route | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| ICE 75 | Frankfurt Hbf – Mannheim – Neustadt – Kaiserslautern – Homburg – Saarbrücken | Some services |

| ICE 50 | Dresden – Leipzig – Erfurt – Frankfurt (Main) – Darmstadt – Mannheim - Neustadt – Kaiserslautern – Saarbrücken | Some services |

| IC 50 | Frankfurt – Darmstadt – Mannheim – Neustadt – Kaiserslautern – Homburg – Saarbrücken | Some services |

| IC/EC 62 | Saarbrücken – Homburg – Neustadt – Mannheim – Heidelberg – Stuttgart – Ulm – Munich – Rosenheim – Salzburg – Graz | Some services |

Local services

_Hauptbahnhof-_auf_Bahnsteig_zu_Gleis_5-_Richtung_Kaiserslautern_(RE_612_641)_11.10.2009.jpg)

A total of 8,017 persons used the line during its first month of operations.[43] After the opening of the Northern Railway in 1873, passenger trains often continued to go past Monsheim for several decades to Marnheim on the Langmeil–Monsheim railway.[44][45] In the summer of 1914, the local traffic trains on the Alsenz Valley, instead of running to Kaiserslautern, ran on the Bad Münster–Neustadt route, requiring a reversal in Hochspeyer station.[46]

After the First World War, local services to the south rarely continued to Wissembourg. After 1930 only one train ran from Neustadt to Wissembourg. In the opposite direction, there was no service between the two towns that did not require a change of trains.[47] A similar picture emerged after the Second World War. There were not, with a few exceptions, direct services from Wissembourg, which was again the French border station, to Neustadt; instead a change in Landau was required.[48] The traffic towards Wörth and Karlsruhe increased in importance because of the loss of traffic on the southern section of the Maximilian Railway which crosses the German-French border. On the Northern Railway there was now no direct services to Monsheim; instead, a change in Grünstadt and sometimes in Freinsheim was necessary, as within the northern part of Bad Dürkheim district, traffic flows towards Ludwigshafen and Frankenthal.

| Line | Route | Line name | KBS | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S 1 | Homburg – Kaiserslautern – Neustadt – Mannheim – Mosbach – Osterburken | Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn | 665.1-2 | DB Regio RheinNeckar |

| S 2 | Kaiserslautern – Neustadt – Mannheim – Mosbach | Rhine-Neckar S-Bahn | 665.1-2 | DB Regio RheinNeckar |

| RE 1 | Mannheim – Neustadt – Kaiserslautern – Saarbrücken – Trier – Koblenz | SÜWEX | 670 | DB Regio Südwest |

| RE 6 | (Kaiserslautern –) Neustadt – Landau (Pfalz) – Winden (Pfalz) – Wörth (Rhein) – Karlsruhe | Palatine Maximilian Railway | 676 | DB Regio RheinNeckar |

| RB 45 | Neustadt – Bad Dürkheim – Freinsheim – Grünstadt (– Monsheim) | Palatine Northern Railway | 667 | DB Regio RheinNeckar |

| RB 49 | Ludwigshafen BASF – Ludwigshafen – Neustadt – Kaiserslautern / Germersheim – Wörth (Rhein) | BASF works services | 670 677 |

DB Regio RheinNeckar |

| RB 51 | Neustadt – Landau (Pfalz) – Winden – Karlsruhe | Palatine Maximilian Railway | 676 | DB Regio RheinNeckar |

| RB 53 | Neustadt – Landau (Pfalz) – Winden – Wissembourg | Palatine Ludwig Railway | 679 | DB Regio RheinNeckar |

On Sundays and public holidays from May to October, the excursion train Bundenthaler runs to the destinations of Bundenthal-Rumbach/Pirmasens. The train splits in Hinterweidenthal Ost. The excursion trains Weinstraßen-Express and Elsass-Express also run to Wissembourg. The Rheintal-Express runs via Bad Kreuznach and Bingen (Rhein) Hbf to Koblenz.

Freight

Before the completion of the Ludwig Railway, the station served as a transhipment station for freight from Ludwigshafen for two years.[49] Since the original freight-handling facilities had become increasingly congested, the Palatinate Railway (Pfälzische Eisenbahnen) bought sites in 1881 in the "Gewitalwiesen" and "Hölzel" areas, in order to build a new freight yard there.[50] The Internationale Baumaschinenfabrik (IBAG) company also had a connecting track in this area.[47] In the 1980s, the functions of the stations of Bad Dürkheim, Deidesheim, Edenkoben, Frankenstein (Pfalz), Lambrecht (Pfalz), Maikammer-Kirrweiler, Mußbach, Wachenheim and Weidenthal were no longer independent freight depots and were now sub-depots of Neustadt Hauptbahnhof. Therefore, Übergabezüge (goods exchange trains) connected to the surrounding stations.[51]

Sources

References

- 1 2 "Stationspreisliste 2017" [Station price list 2017] (PDF) (in German). DB Station&Service. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ Eisenbahnatlas Deutschland (German railway atlas) (2009/2010 ed.). Schweers + Wall. 2009. ISBN 978-3-89494-139-0.

- ↑ "Die Bahnhöfe der Königlich Bayerischen Staatseisenbahnen – linksrheinisch (bayerische Pfalz) – Maikammer bis Oppau" (in German). kbaystb.de. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Nachrichtliches Verzeichnis der Kulturdenkmäler – Kreisfreie Stadt Neustadt an der Weinstraße" (PDF; 1.4 MB) (in German). denkmallisten.gdke-rlp.de. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "113 - (ehem. preuß.-pfälz. Grenze b. Bexbach 0,0) - Homburg (Saar) Hbf 8,37 - Kaiserslautern Hbf 43,70 - Neustadt (Weinstr) Hbf 77,21 - Ludwigshafen (Rhein) Hbf 106,535 (kommend)/105,613 (gehend) - Landesgrenze Pfalz/Hessen km 125,10 = km 0,0 - Worms 3,21 - Mainz Hbf 49,09" (in German). klauserbeck.de. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ↑ "Die Kursbuchstrecke 670 – Streckenverlauf -- Kilometrierung" (in German). kbs-670.de. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). pp. 104f.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). pp. 67f.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 84.

- ↑ Gerhard Hitschler; Marcus Klein; Thomas Gierth (2010). Die Fahrzeuge und Anlagen des Eisenbahnmuseums Neustadt an der Weinstraße – Der Museumsführer (in German). p. 11.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 87ff.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 85ff.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 96.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt–Straßburg (in German). p. 15.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt–Straßburg (in German). pp. 15ff.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 169.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 169f.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt–Straßburg (in German). p. 16.

- 1 2 Modell- und Eisenbahnclub Landau in der Pfalz e. V. (1980). 125 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt/Weinstr.–Landau/Pfalz (in German). p. 79.

- ↑ 125 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt/Weinstr.–Landau/Pfalz (in German). Modell- und Eisenbahnclub Landau in der Pfalz e. V. 1980. p. 47.

- ↑ Albert Mühl (1982). Die Pfalzbahn (in German). p. 116.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt–Straßburg (in German). pp. 27ff.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 265.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 122.

- ↑ Albert Mühl (1982). Die Pfalzbahn (in German). p. 145.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 126.

- ↑ Fritz Engbarth (2007). Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan – 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (in German). p. 13.

- ↑ Fritz Engbarth (2007). Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan – 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (in German). p. 23f.

- ↑ Klaus Detlef Holzborn (1993). Eisenbahn-Reviere Pfalz (in German). pp. 88f.

- ↑ Fritz Engbarth (2007). Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan – 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (in German). p. 28.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt-Straßburg (in German). p. 145.

- ↑ Walter Jonas (2001). "Vorwort". Elektronische Stellwerke bedienen. Der Regelbetrieb (in German). Bahn Fachverlag. p. 8. ISBN 9783980800204.

- ↑ Fritz Engbarth (2007). Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan – 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (in German). p. 27.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 139.

- ↑ Fritz Engbarth (2007). Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan - 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (2007) (in German). p. 61.

- ↑ Gerhard Hitschler; Marcus Klein; Thomas Gierth (2010). Die Fahrzeuge und Anlagen des Eisenbahnmuseums Neustadt an der Weinstraße – Der Museumsführer (in German). p. 9.

- ↑ Fritz Engbarth (2007). Von der Ludwigsbahn zum Integralen Taktfahrplan – 160 Jahre Eisenbahn in der Pfalz (in German). p. 10.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 141.

- ↑ Albert Mühl (1982). Die Pfalzbahn (in German). pp. 11f.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 119.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt-Straßburg (in German). pp. 26f.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 157.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 80.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 205.

- ↑ Albert Mühl (1982). Die Pfalzbahn (in German). p. 141.

- ↑ Ulrich Hauth (2011). Von der Nahe in die Ferne. Zur Geschichte der Eisenbahnen in der Nahe-Hunsrück-Region (in German). p. 164.

- 1 2 Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 134.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt-Straßburg (in German). pp. 70 ff.

- ↑ Heinz Sturm (2005). Die pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 95.

- ↑ Werner Schreiner (2010). Paul Camille von Denis. Europäischer Verkehrspionier und Erbauer der pfälzischen Eisenbahnen (in German). p. 118.

- ↑ Michael Heilmann; Werner Schreiner (2005). 150 Jahre Maximiliansbahn Neustadt-Straßburg (in German). p. 103.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neustadt (Weinstraße) Hauptbahnhof. |

- "Track plan" (PDF) (in German). Deutsche Bahn. Retrieved 16 April 2017.