Neuroptera

| Neuroptera Temporal range: 299–0 Ma Permian to recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Green lacewing | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| (unranked): | Neuropterida |

| Order: | Neuroptera Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Suborders | |

|

and see text | |

The insect order Neuroptera, or net-winged insects, includes the lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, and their relatives. The order consists of some 6,000 species.[1] The group was once known as Planipennia, and at that time also included alderflies, fishflies, dobsonflies, and snakeflies, but these are now separate orders (the Megaloptera and Raphidioptera).

Adult Neuropterans have four membranous wings, all about the same size, with many veins. They have chewing mouthparts, and undergo complete metamorphosis.

Neuropterans first appeared during the Permian Period, and continued to diversify through the Mesozoic Era.[2] During this time, several unusually large forms evolved, especially in the extinct family Kalligrammatidae, often referred to as "the butterflies of the Jurassic" due to their large, patterned wings.[3]

Anatomy and biology

Neuropterans are soft-bodied insects with relatively few specialised features. They have large lateral compound eyes, and may or may not also have ocelli. Their mouthparts have strong mandibles suitable for chewing, and lack the various adaptations found in most other endopterygote insect groups.

They have four wings, which are usually similar in size and shape, and a generalised pattern of veins. Some neuropterans have specialised sense organs in their wings, or have bristles or other structures to link their wings together during flight.[4]

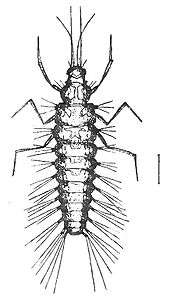

The larvae are specialised predators, with elongated mandibles adapted for piercing and sucking. The larval body form varies between different families, depending on the nature of their prey. In general, however, they have three pairs of thoracic legs, each ending in two claws. The abdomen often has adhesive discs on the last two segments.[4]

Life cycle and ecology

Lifecycle of lacewings | |

Larva of Osmylus fulvicephalus, Osmylidae |

Larva of Sisyra sp., Sisyridae |

The larvae of most families are predators. Many chrysopids eat aphids and other pest insects, and have been used for biological control (either from commercial distributors, but also abundant and widespread in nature). Larvae in various families cover themselves in debris (sometimes including dead prey insects) as camouflage, taken to an extreme in the ant lions, which bury themselves completely out of sight and ambush prey from "pits" in the soil. Larvae of some Ithonidae are root feeders, and larvae of Sisyridae are aquatic, and feed on freshwater sponges. A few mantispids are parasites of spider egg sacs.

As in other holometabolic orders, the pupal stage generally is enclosed in some form of cocoon composed of silk and soil or other debris. The pupa eventually cuts its way out of the cocoon with its mandibles, and may even move about for a short while before undergoing the moult to the adult form.[4]

Adults of many groups are also predatory, but some do not feed, or consume only nectar.

In human culture

The use of Neuroptera in biological control of insect pests has been investigated, showing that it is difficult to establish and maintain populations in fields of crops.[5]

Neuroptera have artistic demonstrations since beginning of civilizations, which can be found in numerous art galleries such as Lacewing Design Gallery and Studio of Northampton, Lacewing fine art of Salisbury.[6]

A song on the 1999 album Suburban Light by The Clientele, "Lacewings", describes watching the insects under the influence of drugs (most likely marijuana).[7][8][9]

The New Guinea Highland people claim to be able to maintain a muscular build and great stamina despite their low protein intake as a result of eating Neuroptera among other insects.[10]

Taxonomy and systematics

The understanding of neuropteran phylogeny has vastly improved since the mid-1990s, not the least courtesy of the ever-growing fossil record.[1] In 1995, for example, it was simply known that the Megaloptera and Raphidioptera were not part of the Neuroptera in the strict sense, and the Mantispoidea and part of the Myrmeleontoidea were the only groups that could be confirmed by cladistic analysis.[11] Though the relationships of some families remain to be fully understood, most major lineages of the Neuropterida can nowadays be robustly placed in an evolutionary context.[12][13][14]

The phylogeny of the Neuroptera has been explored using mitochondrial DNA sequences, and while issues remain for the group as a whole (the traditional "Hemerobiiformia" being agreed (2014) to be paraphyletic), the Myrmeleontiformia is generally agreed to be monophyletic, giving the following cladogram:[15]

| Neuroptera |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Basal and unresolved forms

- Genus Mantispidiptera Grimaldi, 2000 (Late Cretaceous; New Jersey; formerly Mantispidae)

- Genus Mesohemerobius Ping, 1928(Late Jurassic/Early Cretaceous; China)

- Family Permithonidae (fossil, probably paraphyletic)

- Family Prohemerobiidae (fossil, probably paraphyletic)

- Family Nevrorthidae[Note 1]

- Family Grammosmylidae (fossil)

- Family Osmylitidae (fossil, probably paraphyletic)

- Superfamily Osmyloidea (formerly in Hemerobiiformia, basal in crown group)

- Family Osmylidae: osmylids

Suborder Hemerobiiformia (core group, paraphyletic?)

- Superfamily Ithonioidea

- Family Ithonidae: moth lacewings (includes Rapismatidae)

- Family Polystoechotidae: giant lacewings (formerly in Hemerobioidea)

- Superfamily Chrysopoidea

- Family Ascalochrysidae (fossil)

- Family Mesochrysopidae (fossil)

- Family Chrysopidae: green lacewings, stinkflies (formerly in Hemerobioidea)

- Superfamily Hemerobioidea

- Family Hemerobiidae: brown lacewings

- Superfamily Coniopterygoidea

- Family Coniopterygidae: dustywings

- Family Sisyridae: spongillaflies (formerly in Osmyloidea, tentatively placed here)

- Superfamily Mantispoidea

- Family Dilaridae: pleasing lacewings (formerly in Hemerobioidea)

- Family Mantispidae: mantidflies

- Family Mesithonidae (fossil, probably paraphyletic)

- Family Rhachiberothidae: thorny lacewings

- Family Berothidae: beaded lacewings

Suborder Myrmeleontiformia

- Superfamily Nemopteroidea

- Family Kalligrammatidae (fossil)

- Family Psychopsidae: silky lacewings (formerly in Hemerobioidea)

- Family Nemopteridae: spoonwings, spoon-winged laceflies, thread-winged laceflies (formerly in Myrmeleontoidea)

- Superfamily Myrmeleontoidea

- Family Osmylopsychopidae (fossil)

- Family Nymphitidae (fossil)

- Family Solenoptilidae (fossil, probably paraphyletic)

- Family Brogniartiellidae (fossil)

- Family Nymphidae: split-footed lacewings (includes Myiodactylidae)

- Family Babinskaiidae (fossil)

- Family Myrmeleontidae: antlions (includes Palaeoleontidae)

- Family Ascalaphidae: owlflies, ascalaphids

Notes

References

- 1 2 David Grimaldi & Michael S. Engel (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82149-5.

- ↑ A. G. Ponomarenko & D. E. Shcherbakov (2004). "New lacewings (Neuroptera) from the terminal Permian and basal Triassic of Siberia" (PDF). Paleontological Journal. 38 (S2): S197–S203.

- ↑ Michael S. Engel (2005). "A remarkable kalligrammatid lacewing from the Upper Jurassic of Kazakhstan (Neuroptera: Kalligrammatidae)". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 108 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2005)108[0059:ARKLFT]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 Hoell, H.V., Doyen, J.T. & Purcell, A.H. (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press. pp. 447–450. ISBN 0-19-510033-6.

- ↑ Xu, X. X. (2014). "Electrophysiological and Behavior Responses of Chrysopa phyllochroma (Neuroptera Chrysopidae) to Plant Volatiles". Environmental Entomology. 44 (5): 1425–1433. ISSN 0046-225X. doi:10.1093/ee/nvv106.

- ↑ Monserrat, Victor (2010). LOS NEURÓPTEROS (INSECTA: NEUROPTERA) EN EL ARTE. Madrid: Universidad Complutense.

- ↑ http://theclientele.co.uk/lyrics/46/lacewings

- ↑ https://www.mergerecords.com/suburban-light-reissue

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9hjGdtR8A3Q

- ↑ MacClancy, Jeremy (2007). Consuming the Inedible: Neglected Dimensions of Food Choice. Berghahn.

- ↑ John D. Oswald (1995). "Neuroptera. Lacewings, antlions, owlflies, etc.". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Grimaldi, D. A. & Engel, M. S., 2005: Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pages xv-755

- ↑ Engel, M. S. & Grimaldi, D. A., 2007: The neuropterid fauna of Dominican and Mexican amber (Neuropterida: Megaloptera, Neuroptera). American Museum Novitates: #3587, pages 1-58

- ↑ Parker, S. P. (ed.), 1982: Synopsis and classification of living organisms. Vols. 1 & 2. McGrew-Hill Book Company

- ↑ Yan, Y.; Wang Y, Liu, X.; Winterton, S.L.; Yang, D. (2014). "The First Mitochondrial Genomes of Antlion (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) and Split-footed Lacewing (Neuroptera: Nymphidae), with Phylogenetic Implications of Myrmeleontiformia". Int J Biol Sci. 10 (8): 895–908. doi:10.7150/ijbs.9454.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neuroptera. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Neuroptera |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Neuroptera |

- Illustrated database of Neuroptera (insects)

- A database of Neuroptera related scientific literature

- Brown lacewings of Florida on the University of Florida / Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Featured Creatures website

- http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=UA&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=1&SID=2B1m2sz35fQpYa2NV7c&page=1&doc=4