Nestlé

Good Food, Good Life | |

|

| |

| Public | |

| Traded as | SIX: NESN |

| ISIN | CH0038863350 |

| Industry | Food processing |

| Founded |

1866 (as Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company) 1867 (as Farine Lactée Henri Nestlé) 1905 (as Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company) |

| Founder | Henri Nestlé, Charles Page, George Page |

| Headquarters | Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

Paul Bulcke[1] (Chairman) Ulf Mark Schneider[1] (CEO) |

| Products | Baby food, coffee, dairy products, breakfast cereals, confectionery, bottled water, ice cream, pet foods (list...) |

| Revenue |

|

|

| |

| Profit |

|

| Total assets |

|

| Total equity |

|

Number of employees | 335,000 (2016)[2] |

| Website | Official website |

Nestlé S.A. is a Swiss transnational food and drink company headquartered in Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland. It has been the largest food company in the world, measured by revenues and other metrics, for 2014, 2015, and 2016.[3][4][5][6] It ranked No. 72 on the Fortune Global 500 in 2014[7] and No. 33 on the 2016 edition of the Forbes Global 2000 list of largest public companies.[8]

Nestlé's products include baby food, medical food, bottled water, breakfast cereals, coffee and tea, confectionery, dairy products, ice cream, frozen food, pet foods, and snacks. Twenty-nine of Nestlé's brands have annual sales of over CHF1 billion (about US$1.1 billion),[9] including Nespresso, Nescafé, Kit Kat, Smarties, Nesquik, Stouffer's, Vittel, and Maggi. Nestlé has 447 factories, operates in 194 countries, and employs around 339,000 people.[10] It is one of the main shareholders of L'Oreal, the world's largest cosmetics company.[11]

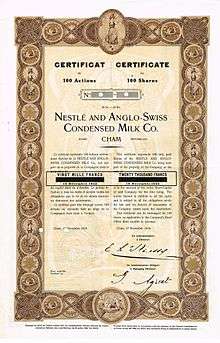

Nestlé was formed in 1905 by the merger of the Anglo-Swiss Milk Company, established in 1866 by brothers George and Charles Page, and Farine Lactée Henri Nestlé, founded in 1866 by Henri Nestlé (born Heinrich Nestle). The company grew significantly during the First World War and again following the Second World War, expanding its offerings beyond its early condensed milk and infant formula products. The company has made a number of corporate acquisitions, including Crosse & Blackwell in 1950, Findus in 1963, Libby's in 1971, Rowntree Mackintosh in 1988, and Gerber in 2007.

Nestlé has a primary listing on the SIX Swiss Exchange and is a constituent of the Swiss Market Index. It has a secondary listing on Euronext.

History

1866–1900: Founding and early years

Nestlé's origins date back to 1866 when two separate Swiss enterprises were founded that would later form the core of Nestlé. In the succeeding decades, the two competing enterprises aggressively expanded their businesses throughout Europe and the United States.

In September 1866, in Vevey, Henri Nestlé developed milk-based baby food and soon began marketing it. The following year saw Daniel Peter begin seven years of work perfecting his invention, the milk chocolate manufacturing process. Nestlé was the crucial co-operation that Peter needed to solve the problem of removing all the water from the milk added to his chocolate and thus preventing the product from developing mildew. Henri Nestlé retired in 1875 but the company, under new ownership, retained his name as Société Farine Lactée Henri Nestlé.

In August 1867, Charles (US consul in Switzerland) and George Page, two brothers from Lee County, Illinois, USA, established the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company in Cham, Switzerland. Their first British operation was opened at Chippenham, Wiltshire, in 1873.[12]

In 1877, Anglo-Swiss added milk-based baby foods to their products; in the following year, the Nestlé Company added condensed milk to their portfolio, which made the firms direct and fierce rivals.

In 1879, Nestle merged with milk chocolate inventor Daniel Peter.

1901–1989: Mergers

In 1904, François-Louis Cailler, Charles Amédée Kohler, Daniel Peter, and Henri Nestlé participated in the creation and development of Swiss chocolate, marketing the first chocolate – milk Nestlé.[13]

In 1905, the companies merged to become the Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company, retaining that name until 1947 when the name 'Nestlé Alimentana SA' was taken as a result of the acquisition of Fabrique de Produits Maggi SA (founded 1884) and its holding company, Alimentana SA, of Kempttal, Switzerland. Maggi was a major manufacturer of soup mixes and related foodstuffs. The company's current name was adopted in 1977. By the early 1900s, the company was operating factories in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Spain. The First World War created demand for dairy products in the form of government contracts, and, by the end of the war, Nestlé's production had more than doubled.

In January 1919, Nestlé bought two condensed milk plants in Oregon from the company Geibisch and Joplin for $250,000. One was in Bandon, and the other was in Milwaukee. They expanded them considerably, processing 250,000 pounds of condensed milk daily in the Bandon plant.[14]

Nestlé felt the effects of the Second World War immediately. Profits dropped from US$20 million in 1938 to US$6 million in 1939. Factories were established in developing countries, particularly in Latin America. Ironically, the war helped with the introduction of the company's newest product, Nescafé ("Nestlé's Coffee"), which became a staple drink of the US military. Nestlé's production and sales rose in the wartime economy.

After the war, government contracts dried up, and consumers switched back to fresh milk. However, Nestlé's management responded quickly, streamlining operations and reducing debt. The 1920s saw Nestlé's first expansion into new products, with chocolate-manufacture becoming the company's second most important activity. Louis Dapples was CEO till 1937 when succeeded by Édouard Muller till his death in 1948.

The end of World War II was the beginning of a dynamic phase for Nestlé. Growth accelerated and numerous companies were acquired. In 1947 Nestlé merged with Maggi, a manufacturer of seasonings and soups. Crosse & Blackwell followed in 1950, as did Findus (1963), Libby's (1971), and Stouffer's (1973). Diversification came with a shareholding in L'Oreal in 1974. In 1977, Nestlé made its second venture outside the food industry, by acquiring Alcon Laboratories Inc.

In the 1980s, Nestlé's improved bottom line allowed the company to launch a new round of acquisitions. Carnation was acquired for $3 billion in 1984 and brought the evaporated milk brand, as well as Coffee-Mate and Friskies to Nestlé. The confectionery company Rowntree Mackintosh was acquired in 1988 for $4.5 billion, which brought brands such as Kit Kat, Smarties, and Aero.

1990–2011: Growth internationally

The first half of the 1990s proved to be favourable for Nestlé. Trade barriers crumbled, and world markets developed into more or less integrated trading areas. Since 1996, there have been various acquisitions, including San Pellegrino (1997), Spillers Petfoods (1998), and Ralston Purina (2002). There were two major acquisitions in North America, both in 2002 – in June, Nestlé merged its US ice cream business into Dreyer's, and in August, a US$2.6 billion acquisition was announced of Chef America, the creator of Hot Pockets. In the same time-frame, Nestlé entered in a joint bid with Cadbury and came close to purchasing the iconic American company Hershey's, one of its fiercest confectionery competitors, but the deal eventually fell through.[15]

In December 2005, Nestlé bought the Greek company Delta Ice Cream for €240 million. In January 2006, it took full ownership of Dreyer's, thus becoming the world's largest ice cream maker, with a 17.5% market share.[16] In July 2007, completing a deal announced the year before, Nestlé acquired the Medical Nutrition division of Novartis Pharmaceutical for US$2.5 billion, also acquiring, the milk-flavoring product known as Ovaltine, the "Boost" and "Resource" lines of nutritional supplements, and Optifast dieting products.[17]

In April 2007, returning to its roots, Nestlé bought US baby-food manufacturer Gerber for US$5.5 billion.[18][19][20] In December 2007, Nestlé entered into a strategic partnership with a Belgian chocolate maker, Pierre Marcolini.[21]

Nestlé agreed to sell its controlling stake in Alcon to Novartis on 4 January 2010. The sale was to form part of a broader US$39.3 billion offer, by Novartis, for full acquisition of the world's largest eye-care company.[22] On 1 March 2010, Nestlé concluded the purchase of Kraft Foods's North American frozen pizza business for US$3.7 billion.

Since 2010, Nestle has been working to transform itself into a nutrition, health and wellness company in an effort to combat declining confectionery sales and the threat of expanding government regulation of such foods. This effort is being led through the Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences under the direction of Ed Baetge. The Institute aims to develop "a new industry between food and pharmaceuticals" by creating foodstuffs with preventative and corrective health properties that would replace pharmaceutical drugs from pill bottles. The Health Science branch has already produced several products, such as drinks and protein shakes meant to combat malnutrition, diabetes, digestive health, obesity, and other diseases.[23]

In July 2011, Nestlé SA agreed to buy 60 percent of Hsu Fu Chi International Ltd. for about US$1.7 billion.[24] On 23 April 2012, Nestlé agreed to acquire Pfizer Inc.'s infant-nutrition, formerly Wyeth Nutrition, unit for US$11.9 billion, topping a joint bid from Danone and Mead Johnson.[25][26][27]

2012–2017: Recent developments

In recent years, Nestlé Health Science has made several acquisitions. It acquired Vitaflo, which makes clinical nutritional products for people with genetic disorders; CM&D Pharma Ltd., a company that specialises in the development of products for patients with chronic conditions like kidney disease; and Prometheus Laboratories, a firm specialising in treatments for gastrointestinal diseases and cancer. It also holds a minority stake in Vital Foods, a New Zealand-based company that develops kiwifruit-based solutions for gastrointestinal conditions as of 2012.[28]

Another recent purchase included the Jenny Craig weight-loss program, for US$600 million. Nestlé sold the Jenny Craig business unit to North Castle Partners in 2013.[29] In February 2013, Nestlé Health Science bought Pamlab, which makes medical foods based on L-methylfolate targeting depression, diabetes, and memory loss.[30] In February 2014, Nestlé sold its PowerBar sports nutrition business to Post Holdings, Inc.[31] Later, in November 2014, Nestlé announced that it was exploring strategic options for its frozen food subsidiary, Davigel.[32]

In December 2014, Nestlé announced that it was opening 10 skin care research centres worldwide, deepening its investment in a faster-growing market for healthcare products. That year, Nestlé spent about $350 million on dermatology research and development. The first of the research hubs, Nestlé Skin Health Investigation, Education and Longevity Development (SHIELD) centres, will open mid 2015 in New York, followed by Hong Kong and São Paulo, and later others in North America, Asia, and Europe. The initiative is being launched in partnership with the Global Coalition on Aging (GCOA), a consortium that includes companies such as Intel and Bank of America.[33]

Nestlé announced in January 2017 that it was relocating its U.S. headquarters from Glendale, California, to Rosslyn, Virginia outside of Washington, DC.[34]

In March 2017, Nestlé announced that they will lower the sugar content in Kit Kat, Yorkie and Aero chocolate bars by 10% by 2018.[35] In July followed a similar announcement concerning the reduction of sugar content in its breakfast cereals in the UK.[36]

The company announced a $20.8 billion share buyback in June 2017, following the publication of a letter written by Third Point founder Daniel Loeb, Nestlé's fourth-largest stakeholder with a $3.5 billion stake,[37] explaining how the firm should change its business structure.[38] Consequently, the firm will reportedly focus investment on sectors such as coffee and pet care and will seek acquisitions in the consumer health-care industry.[38]

Corporate affairs and governance

.jpg)

Nestlé is the biggest food company in the world, with a market capitalisation of roughly 231 billion Swiss francs, which is more than US$247 billion as of May 2015.[39]

In 2014, consolidated sales were CHF 91.61 billion and net profit was CHF 14.46 billion. Research and development investment was CHF 1.63 billion.[40]

- Sales per category in CHF[41][10]

- 20.3 billion powdered and liquid beverages

- 16.7 billion milk products and ice cream

- 13.5 billion prepared dishes and cooking aids

- 13.1 billion nutrition and health science

- 11.3 billion petcare

- 9.6 billion confectionery

- 6.9 billion water

- Percentage of sales by geographic area breakdown[41][10]

- 43% from Americas

- 28% from Europe

- 29% from Asia, Oceania and Africa

According to a 2015 global survey of online consumers by the Reputation Institute, Nestlé has a reputation score of 74.5 on a scale of 1–100.[42]

Joint ventures

Joint ventures include:

- Cereal Partners Worldwide with General Mills (50%/50%)[43]

- Beverage Partners Worldwide with The Coca-Cola Company(50%/50%)[44]

- Lactalis Nestlé Produits Frais with Lactalis (40%/60%)[45]

- Nestlé Colgate-Palmolive with Colgate-Palmolive (50%/50%)[46]

- Nestlé Indofood Citarasa Indonesia with Indofood (50%/50%)[47]

- Nestlé Snow with Snow Brand Milk Products (50%/50%)[48]

- Nestlé Modelo with Grupo Modelo

- Dairy Partners America Brasil with Fonterra (51%/49%)

Board of Directors

As of 2017 the board is composed of:[49]

Paul Bulcke, chairman and former CEO of Nestlé

Andreas Koopmann, former CEO of Bobst

Beat Hess, former legal director/general counsel for ABB Group and Royal Dutch Shell

Renato Fassbind, former CEO of DKSH and former CFO of Credit Suisse

Steven George Hoch, founder of Highmount Capital

Naina Lal Kidwai, former CEO of HSBC Bank India, country head for HSBC in India

Jean-Pierre Roth, former Chairman of the Swiss National Bank

Ann Veneman, former United States Secretary of Agriculture and Director of UNICEF

Henri de Castries, former CEO and Chairman of AXA

Eva Cheng, former Executive Vice President of China and Southeast Asia for Amway

Ruth Khasaya Oniang’o, former member of the Parliament of Kenya, current professor at Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy

Patrick Aebischer, former President of École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

Products

Nestlé has over 8,000 brands[50] with a wide range of products across a number of markets, including coffee, bottled water, milkshakes and other beverages, breakfast cereals, infant foods, performance and healthcare nutrition, seasonings, soups and sauces, frozen and refrigerated foods, and pet food.[10]

Food safety

Milk products and baby food

In late September 2008, the Hong Kong government found melamine in a Chinese-made Nestlé milk product. Six infants died from kidney damage, and a further 860 babies were hospitalised.[51][52] The Dairy Farm milk was made by Nestlé's division in the Chinese coastal city Qingdao.[53] Nestlé affirmed that all its products were safe and were not made from milk adulterated with melamine. On 2 October 2008, the Taiwan Health ministry announced that six types of milk powders produced in China by Nestlé contained low-level traces of melamine, and were "removed from the shelves".[54] As of 2013, Nestlé has implemented initiatives to prevent contamination and utilizes what it calls a "factory and farmers" model that eliminates the middleman. Farmers bring milk directly to a network of Nestlé-owned collection centers, where a computerized system samples, tests, and tags each batch of milk. To reduce further the risk of contamination at the source, the company provides farmers with continuous training and assistance in cow selection, feed quality, storage, and other areas.[55] In 2014, the company opened the Nestlé Food Safety Institute (NFSI) in Beijing that will help meet China's growing demand for healthy and safe food, one of the top three concerns among Chinese consumers. The NFSI announced it would work closely with authorities to help provide a scientific foundation for food-safety policies and standards, with support to include early management of food-safety issues and collaboration with local universities, research institutes and government agencies on food-safety.[56] In an incident in 2015, weevils and fungus were found in Cerelac baby food.[57][58][59]

Cookie dough

In June 2009, an outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 was linked to Nestlé's refrigerated cookie dough originating in a plant in Danville, Virginia. In the US, it caused sickness in more than 50 people in 30 states, half of whom required hospitalisation. Following the outbreak, Nestlé voluntarily recalled 30,000 cases of the cookie dough. The cause was determined to be contaminated flour obtained from a raw material supplier. When operations resumed, the flour used was heat-treated to kill bacteria.[60]

Maggi noodles

In May 2015, Food Safety Regulators from the Uttar Pradesh, India found that samples of Nestlé's leading noodles Maggi had up to 17 times beyond permissible safe limits of lead in addition to monosodium glutamate.[61][62][63] On June 3, 2015, New Delhi Government banned the sale of Maggi in New Delhi stores for 15 days because it found lead and monosodium glutamate in the eatable beyond permissible limit.[64] Some of India's biggest retailers like Future Group, Big Bazaar, Easyday, and Nilgiris had imposed a nationwide ban on Maggi as of June 3, 2015.[65] On June 3, 2015, Nestlé India's shares fell down 11% due to the incident.[66] Thereafter, multiple state authorities in India found unacceptable amount of lead and it had been banned in more than 5 other states in India by June 4, 2015.[67] The Gujarat FDA on June 4, 2015, banned the noodles for 30 days after 27 out of 39 samples were detected with objectionable levels of metallic lead, among other things.[68] On June 4, 2015, Nestlé's share fell down by 3% over concerns related to its safety standards.[69] On June 5, 2015, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) orders banned all nine approved variants of Maggi instant noodles from India, terming them "unsafe and hazardous" for human consumption.[70] On June 5, 2015 Nepal indefinitely banned Maggi over concerns about lead levels in the product.[71] On June 5, 2015, the Food Safety Agency, United Kingdom launched an investigation to find levels of lead in Maggi.[72] Maggi noodles has been withdrawn in five African nations - Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and South Sudan by a super-market chain after a complaint by the Consumer Federation of Kenya, as a reaction to the ban in India.[73]

As of August 2015, India's government made public that it was seeking damages of nearly $100 million from Nestlé India for "unfair trade practices" following the June ban on Maggi noodles.[74] The 6,400 million rupee suit was filed with the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (NCDRC), regarded as the country's top consumer court, but was settled on 13 August 2015.[75] The court ruled that the government ban on the Nestlé product was both "arbitrary" and had violated the "principles of natural justice."[76] Although Nestlé was not ordered to pay the fine requested in the government's suit, the court ruled that the Maggi noodle producers must "send five samples from each batch of Maggi [noodles] for testing to three labs and only if the lead is found to be lower than permitted will they start manufacturing and sale again." Although the tests have yet to take place, Nestlé has already destroyed 400 million packets of Maggi products.[77]

Sponsorships

Animation In 1993, plans were made to update and modernise the overall tone of Walt Disney's EPCOT Center, including a major refurbishment of The Land pavilion. Kraft Foods withdrew its sponsorship on 26 September 1993, with Nestlé taking its place. Co-financed by Nestlé and the Walt Disney World Resort, a gradual refurbishment of the pavilion began on 27 September 1993.[78] In 2003, Nestlé renewed its sponsorship of The Land; however, it was under agreement that Nestlé would oversee its own refurbishment to both the interior and exterior of the pavilion. Between 2004 and 2005, the pavilion underwent its second major refurbishment. Nestlé's withdrawal from the Land dates back from 2009.[79]

Music festivals On 5 August 2010, Nestlé and the Beijing Music Festival signed an agreement to extend by three years Nestlé's sponsorship of this international music festival. Nestlé has been an extended sponsor of the Beijing Music Festival for 11 years since 2000. The new agreement will continue the partnership through 2013.[80]

Nestlé has partnered the prestigious Salzburg Festival in Austria for 20 years. In 2011, Nestlé renewed its sponsorship of the Salzburg Festival until 2015.[81]

Together, they have created the "Nestlé and Salzburg Festival Young Conductors Award," an initiative that aims to discover young conductors globally and to contribute to the development of their careers.[82]

Sports Nestlé's sponsorship of the Tour de France began in 2001 and the agreement was extended in 2004, a move which demonstrated the company's interest in the Tour. In July 2009, Nestlé Waters and the organisers of the Tour de France announced that their partnership will continue until 2013. The main promotional benefits of this partnership will spread on four key brands from Nestlé's product portfolio: Vittel, Powerbar, Nesquik, or Ricore.[83]

In 2014, Nestlé Waters sponsored the UK leg of the Tour de France through its Buxton Natural Mineral Water brand.[84] In 2002, Nestlé announced it was main sponsor for the Great Britain Lionesses Women's rugby league team for the team's second tour of Australia with its Munchies product.[85]

On 27 January 2012, the International Association of Athletics Federations announced that Nestlé will be the main sponsor for the further development of IAAF's Kids' Athletics Programme, which is one of the biggest grassroots development programmes in the world of sports. The five-year sponsorship started in January 2012.[86] On 11 February 2016, Nestlé decided to withdraw its sponsorship of the IAAF's Kids' Athletics Programmes because of doping and corruption allegations against the IAAF. Nestlé followed suit after other large sponsors, including Adidas, also stopped supporting the IAAF.[87]

Nestlé supports the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) on a number of nutrition and fitness fronts, funding a Fellowship position in AIS Sports Nutrition; nutrition activities in the AIS Dining Hall; research activities; and the development of education resources for use at the AIS and in the public domain.[88]

Controversy and criticisms

Nestlé baby formula boycott

A boycott was launched in the United States on 7 July 1977, against the Swiss-based Nestlé corporation. It spread in the United States, and expanded into Europe in the early 1980s. It was prompted by concern about Nestlé's "aggressive marketing" of breast milk substitutes, particularly in less economically developed countries (LEDCs), largely among the poor.[89] The boycott was officially suspended in the U.S. in 1984, after Nestlé agreed to follow an international marketing code endorsed by the World Health Organization.[90][91] The boycott was also ended in the UK by several organisations including the General Synod of the Church of England in July 1994,[92] the Royal College of Midwives in July 1997,[93] and the Methodist Ethical Investment Committee in November 2005 and the Reformed Churches in November 2011 [94] as a result of the company’s inclusion in the responsible investment index FTSE4Good Responsible Investment Index.[95] Since 2011, Nestlé is the only infant formula manufacturer to have met the 104 criteria on the marketing of breastmilk substitutes (FTSE4Good BMS Criteria) of the FTSE4Good Responsible Investment Index.[96] Nestlé’s inclusion in the index is based on results of independent and transparent verifications conducted by Pricewaterhouse Coopers every 18 months.[97] Every year since 2009, Bureau Veritas - one of the world’s leading verification and auditing firm - conducts independent assurance of compliance with the Nestlé Policy and Instructions for Implementation of the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. Their Assurance Statements are transparently available in the public domain.[98]

Possible competition violations

In May 2011, the debate over Nestlé's unethical marketing of infant formula was relaunched in the Asia-Pacific region. Nineteen leading Laos-based international NGOs, including Save the Children, Oxfam, CARE International, Plan International, and World Vision have launched a boycott of Nestlé and written an open letter to the company.[99] Among other unethical practices, the NGOs criticised the lack of labelling in Laos and the provision of incentives to doctors and nurses to promote the use of infant formula.[100] In November 2011, Bureau Veritas was commissioned by Nestlé S.A. to provide independent assurance of Nestlé Indochina’s compliance with the Nestlé policy for the implementation of the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes (1981). There was no significant evidence that indicated Nestlé Indochina was systematically operating in violation of the WHO Code and Lao PDR Decree in Lao PDR. The presence of promotional materials in retail units constituted a non-conformance, and Bureau Veritas recommended that the Nestlé’s Policy and Procedures Manual on the Marketing of breastmilk substitutes be reviewed and updated to ensure consistency against the more stringent requirements of the Lao PDR Decree.[101] Ernest W. Lefever and the Ethics and Public Policy Center were criticized for accepting a $25,000 contribution from Nestlé while the organization was in the process of developing a report investigating medical care in developing nations which was never published. It was alleged that this contribution affected the release of the report and led to the author of the report submitting an article to Fortune Magazine praising the company's position.[102]

Nestlé has been under investigation in China since 2011 over allegations that the company bribed hospital staff to obtain the medical records of patients and push its infant formula to increase sales.[103] This was found to be in violation of a 1995 Chinese regulation that aims to secure the impartiality of medical staff by banning hospitals and academic institutions from promoting instant formula to families.[104] As a consequence, six Nestlé employers were given prison sentences between one and six years.[103]

Status of Potable Water

At the second World Water Forum in 2000, Nestlé and other corporations persuaded the World Water Council to change its statement so as to reduce access to drinking water from a "right" to a "need." Nestlé chairman and former CEO Peter Brabeck-Letmathe stated that "access to water should not be a public right." Nestlé continues to take control of aquifers and bottle their water for profit.[105] Peter Brabeck-Letmathe later changed his statement.[106]

Ethiopian debt (2002)

In 2002, Nestlé demanded that the nation of Ethiopia repay US $6 million of debt to the company at a time when Ethiopia was suffering a severe famine. Nestlé backed down from its demand after more than 8,500 people complained via e-mail to the company about its treatment of the Ethiopian government. The company agreed to re-invest any money it received from Ethiopia back into the country.[107] In 2003, Nestlé agreed to accept an offer of US $1.5 million, and donated the money to three active charities in Ethiopia: the Red Cross, Caritas, and UNHCR.[108]

Child labour

In 2005, after the cocoa industry had not met the Harkin–Engel Protocol deadline for certifying that the worst forms of child labour (according to the International Labour Organization's Convention 182) had been eliminated from cocoa production, the International Labor Rights Fund filed a lawsuit in 2005 under the Alien Tort Claims Act against Nestlé and others on behalf of three Malian children. The suit alleged the children were trafficked to Ivory Coast, forced into slavery, and experienced frequent beatings on a cocoa plantation.[109][110] In September 2010, the US District Court for the Central District of California determined corporations cannot be held liable for violations of international law and dismissed the suit. The case was appealed to the US Court of Appeals.[111][112] The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision.[113] In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Nestle's appeal of the Ninth Circuit's decision.[114]

The 2010 documentary The Dark Side of Chocolate brought attention to purchases of cocoa beans from Ivorian plantations that use child slave labour. The children are usually 12 to 15 years old and some are trafficked from nearby countries.[115] The first allegations that child slavery is used in cocoa production appeared in 1998.[116] In late 2000, a BBC documentary reported the use of enslaved children in the production of cocoa in West Africa.[116][117][118] Other media followed by reporting widespread child slavery and child trafficking in the production of cocoa.[119][120] In September 2001, Bradley Alford, Chairman and CEO of Nestlé USA, signed the Harkin–Engel Protocol (commonly called the Cocoa Protocol), an international agreement aimed at ending child labour in the production of cocoa.

The 2014 Assessments of Shared Hazelnut Supply Chain In Turkey, published by the Fair Labor Association, identified "a total of 46 child workers younger than 15 years" as well as "a total of 83 young workers (between 15 and 18 years of age) working the same hours as adults and performing similar hazardous and strenuous tasks, such as carrying heavy bags of hazelnuts weighing up to 70 kilograms".[121]

Chocolate price fixing

In Canada, the Competition Bureau raided the offices of Nestlé Canada (along with those of Hershey Canada and Mars Canada) in 2007 to investigate the matter of price fixing of chocolates. It is alleged that executives with Nestlé (the maker of KitKat, Coffee Crisp, and Big Turk) colluded with competitors in Canada to inflate prices.[122]

The Bureau alleged that competitors' executives met in restaurants, coffee shops and at conventions, and that Nestlé Canada CEO, Robert Leonidas once handed a competitor an envelope containing his company’s pricing information, saying: "I want you to hear it from the top – I take my pricing seriously."[122]

Nestlé and the other companies were subject to class-action lawsuits for price fixing after the raids were made public in 2007. Nestlé settled for $9 million, without admitting liability, subject to court approval in the new year. A massive class-action lawsuit continues in the United States.[122]

Former Nestlé Canada CEO Robert Leonidas is under threat of a criminal charge for his role in the price fixing of chocolates in Canada when he was at the helm of Nestlé Canada from 2006 to 2010.[122]

Packaging claims (2008)

A coalition of environmental groups filed a complaint against Nestlé to the Advertising Standards of Canada after Nestlé took out full-page advertisements in October 2008 claiming that "Most water bottles avoid landfill sites and are recycled," "Nestlé Pure Life is a healthy, eco-friendly choice," and that "Bottled water is the most environmentally responsible consumer product in the world."[123][124][125] A spokesperson from one of the environmental groups stated: "For Nestlé to claim that its bottled water product is environmentally superior to any other consumer product in the world is not supportable."[123] In their 2008 Corporate Citizenship Report, Nestlé themselves stated that many of their bottles end up in the solid-waste stream, and that most of their bottles are not recycled.[124][126] The advertising campaign has been called greenwashing.[124][125][126] Nestlé defended its ads, saying they will show they have been truthful in their campaign.[123]

Water bottling operations in California and Oregon

Considerable controversy has surrounded Nestlé's bottled water brand 'Arrowhead' sourced from wells alongside a spring in Millard Canyon situated in a Native American Reservation at the base of the San Bernardino Mountains in California. While corporate officials and representatives of the governing Morongo tribe have asserted that the company, which started its operations in 2000, is providing meaningful jobs in the area and that the spring is sustaining current surface water flows, a number of local citizen groups and environmental action committees have started to question the amount of water drawn in the light of the ongoing drought, and the restrictions that have been placed on residential water use.[127] Additionally, recent evidence suggests that representatives of the Forest Service failed to follow through on a review process for Nestlé's permit to draw water from the San Bernardino wells, which expired in 1988.[128][129] The former forest supervisor Gene Zimmerman has explained that the review process was rigorous, and that the Forest Service "didn't have the money or the budget or the staff" to follow through on the review of Nestlé's long-expired permit.[130] However, Zimmerman's observations and action have come under scrutiny for a number of reasons. Firstly, along with the natural resource manager for Nestlé, Larry Lawrence, Zimmerman is a board member for and played a vital role in the founding of the nonprofit Southern California Mountains Foundation, of which Nestlé is the most noteworthy and longtime donor.[131] Secondly, the Zimmerman Community Partnership Award – an award inspired by Zimmerman's actions and efforts "to create a public/private partnership for resource development and community engagement" – was presented by the foundation to Nestlé's Arrowhead Water division in 2013.[132] Finally, while Zimmerman retired from his former role in 2005, he currently works as a paid consultant for Nestlé, leading many investigative journalists to question Zimmerman's allegiances prior to his retirement from the Forest Service.[130]

In April 2015, the city of Cascade Locks, Oregon and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, which is using water for a salmon hatchery, applied with the Oregon Water Resources Department to permanently trade their water rights to Nestlé; an action which does not require a public-interest review. Nestlé approached them in 2008 and they had been considering to trade their well water with Oregon's Oxbow Springs water, a publicly owned water source in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, and to sell the spring water at over 100 million gallons of water per year to Nestlé. The plan has been criticized by legislators and 80,000 citizens.[133] The 250,000-square-foot, $50 million Nestlé bottling plant in Cascade Locks with an unemployment rate of 18.8 percent would have 50 employees and would increase property-tax collections by 67 percent.[134] The Oregon Water Resources Department was expected to issue a proposal in 2015, that would allow Nestlé to utilise spring water for its bottling operation.[135]

Ukrainian boycott of Russian-manufactured Nestlé products

In August 2015, the Ukrainian TV channel Ukrayina refused to hire a worker of the weekly magazine Krayina, Alla Zheliznyak, as a host of a cooking show because she speaks Ukrainian. The demand to only hire a Russian-speaking host was allegedly set by a sponsor of the show – Nesquik, which is a brand of Nestlé S.A.[136][137] Activists of the Vidsich civil movement held a rally near the office of the company in Kiev, accusing Nestlé of discriminating against people who speak Ukrainian and supporting the Russification of Ukraine.[138] They also added that goods sold in Ukraine are manufactured in Russia. Activists threatened to start a boycott campaign against Nestlé if they will not fulfill their requirements. In September 2015, there were "Russian kills!" flashmobs protesting against Nestlé products that are manufactured in Russia.[139]

Forced labour in Thai fishing industry

At the conclusion of a year-long self-imposed investigation in November 2015, Nestlé disclosed that seafood products sourced in Thailand were produced with forced labour. Nestlé is not a major purchaser of seafood in Southeast Asia, but does some business in Thailand - primarily for its Purina cat food. The study found virtually all U.S. and European companies buying seafood from Thailand are exposed to the same risks of abuse in their supply chains.[140] This type of disclosure was a surprise to many in the industry because international companies rarely acknowledge abuses in supply chains.[141]

Nestlé was expected to launch a yearlong program in 2016 focused on protecting workers across its supply chain. The company has promised to impose new requirements on all potential suppliers, train boat owners and captains about human rights,[140] and hire auditors to check for compliance with new rules.[142]

Corporate social responsibility program involvements

Nestlé efforts relating to social responsibility programs include:

- World Cocoa Foundation: In 2000, Nestlé and other chocolate companies formed the World Cocoa Foundation (WCF). The WCF is an international membership organization representing more than 100 member companies across the cocoa value chain. It is committed to creating a sustainable cocoa economy by putting farmers first, promoting agricultural & environmental stewardship, and strengthening development in cocoa-growing communities.[143]

- Sustainable Agriculture Initiative: In 2002, Nestlé, Unilever, and Danone created the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI) Platform, a non-profit organization to facilitate sharing of knowledge and initiatives to support the development and implementation of sustainable agriculture practices involving the different stakeholders of the food chain. The SAI Platform has more than 60 members, which actively share the same view on sustainable agriculture seen as "the efficient production of safe, high-quality agricultural products, in a way that protects and improves the natural environment, the social and economic conditions of farmers, their employees and local communities, and safeguards the health and welfare of all farmed species." The SAI Platform developed (or co-developed) Principles and Practices for sustainable water management at the farm level; recommendations for Sustainability Performance Assessment (SPA); a standardised methodology for the dairy sector to assess green house gas emissions; an Executives Training on Sustainable Sourcing; and many more.[144] One instance of Nestlé's impact on sustainable agricultural practices has been documented in academic literature.[145]

- Creating Shared Value: Creating Shared Value (CSV) is a business concept intended to encourage businesses to create economic and social value simultaneously by focusing on the social issues that they are capable of addressing. In 2006, Nestlé adopted the CSV approach, focusing on three areas – nutrition, water and rural development – as these are core to their business activities.[144] Nestlé now publishes an annual progress report on its goals.[146] Nestlé CEO Paul Bulcke describes CSV as follows: "Creating Shared Value, these three words, are the fundamental way we want to behave as a company, and by nature, also as persons; it is the fundamental way we want to go about our activities; it also is linked with the conviction that in order to be meaningful and successful, a company must intersect with society in a very positive and constructive way."[147] Nestlé also established the Creating Shared Value Prize, which is awarded every other year with the aim of rewarding the best examples of CSV initiatives worldwide and to encourage other companies to adopt a shared value approach. These initiatives should take a business-oriented approach in addressing challenges in nutrition, water or rural development. The winner can win up to CHF 500,000. Nestlé was an early mover in the shared value space and hosts a global forum, the Creating Shared Value Global Forum.[148][149]

- Nestlé Cocoa Plan: In October 2009, Nestlé announced "The Cocoa Plan." The company is working to get 100 percent of its chocolate portfolio using certified sustainable cocoa. For third-party certification, Nestlé has partnered with UTZ Certified to ensure that best practices are being used. Many of Nestlé’s efforts are focused on the Ivory Coast, where 40 percent of the world's cocoa comes from. The company has developed a higher-yielding, more drought- and disease-resistant cocoa tree; and they have given 3 million of these super trees to farmers thus far and plan to give away 12 million of them in total. They are also training farmers in efficient and sustainable growing techniques, which focuses on better farming practices, including pruning trees, pest control (with an emphasis on integrated pest management) and harvesting, as well as caring for the environment. In addition, they have built 23 new schools so far and plan to build 40 in total by 2015.[150] Another part of the plan has been to address child labor. Nestlé says that according to U.S. statistics, there are about 800,000 children who work the cocoa supply chain. With this in mind, Nestlé approached the Fair Labor Association to map out strategies to help curb child labor in the cocoa sector, and these efforts – including community education and the building of schools – have become a focus of the Cocoa Plan.[150]

- Ecolaboration: On 22 June 2009, Nestlé Nespresso and Rainforest Alliance signed a pact called "Ecolaboration". One of the shared goals is to reduce the environmental impacts and increase the social benefits of coffee cultivation in enough tropical regions so that 80 percent of Nespresso's coffee comes from Rainforest Alliance Certified farms by the year 2013. Certified farms comply with comprehensive standards covering all aspects of sustainable farming, including soil and water conservation, protection of wildlife and forests, and ensuring that farm workers, women and children have all the proper rights and benefits, such as good wages, clean drinking water, access to schools, and health care and security.[151]

- The Nescafé Plan: In 2010, Nestlé launched the Nescafé Plan, an initiative to increase sustainable coffee production and make sustainable coffee farming more accessible to farmers. The plan aims to increase the company’s supply of coffee beans without clearing rainforests, as well as using less water and fewer agrochemicals. According to Nestlé, Nescafé will invest 350 million Swiss francs (about $336 million) over the next ten years to expand the company's agricultural research and training capacity to help benefit many of the 25 million people who make their living growing and trading coffee. The Rainforest Alliance and the other NGOs in the Sustainable Agriculture Network will support Nestlé in meeting the objectives of the plan.[152]

- Health care and nutrition product development: In September 2010, Nestlé said that it would invest more than $500 million between 2011 and 2020 to develop health and wellness products to help prevent and treat major ailments like diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and Alzheimer’s, which are placing an increasing burden on governments at a time when budgets are being squeezed. Nestlé created a wholly owned subsidiary, Nestlé Health Science, as well as a research body, the Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences.[153]

- Membership in Fair Labour Association: In 2011, Nestlé started to work with the Fair Labor Association (FLA), a non-profit, multi-stakeholder association that works with major companies to improve working conditions in developing countries, to assess labor conditions and compliance risks throughout Nestlé’s supply chain of hazelnuts and cocoa. On 29 February 2012, Nestlé became the first company in the food industry to join the FLA. Building on Nestlé's efforts under the Cocoa Plan, the FLA will send independent experts to Ivory Coast in 2012 and where evidence of child labour is found, the FLA will identify root causes and advise Nestlé how to address them in sustainable and lasting ways.[154] As a Participating Company, Nestlé has committed to ten Principles of Fair Labor and Responsible Sourcing, and to upholding the FLA Workplace Code of Conduct throughout their supply chains, starting with farms.[155]

- Rural Development Framework program: In 2012, Nestlé developed the Rural Development Framework, which supports farmers and cocoa growing communities.[156] It is an investment program aimed at improving infrastructure, increasing access to safe water, address financing and market efficiency gaps, and improving labor conditions.[157]

- Partnership with IFRC: Nestlé has had a long-standing partnership with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) to increase access to safe water and sanitation in rural communities. In recent years, the partnership has brought clean drinking water and sanitation facilities to 100,000 people in Ivory Coast's cocoa communities. Nestlé committed to contributing five million Swiss francs during 2014–2019 to the IFRC.[158]

Recognition and awards

- In May 2006, Nestlé's executive board decided to adapt the existing Nestlé management systems to full conformity with the international standards ISO 14001 (Environmental Management Systems) and OHSAS 18001 (Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems) and to certify all Nestlé factories against these standards by 2010.[159] In the meanwhile, a lot of the Nestlé factories have obtained these certifications.

- Nestlé Purina received in 2010 the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award for their excellence in the areas of leadership, customer and market focus, strategic planning, process management, measurement, analysis and knowledge management, workforce focus and results.[160]

- In March 2011, Nestlé became the first infant formula company to meet the FTSE4Good Index criteria in full.[161]

- In September 2011, Nestlé occupied 19th position in the Universum's global ranking of Best Employers Worldwide.[162] According to a survey by Universum Communications, Nestlé was, in 2011, the best employer to work for in Switzerland.[163]

- The International Union of Food Science and Technology (IUFoST) honoured Nestlé in 2010 with the Global Food Industry Award.[164]

- In May 2011, Nestlé won the 27th World Environment Center (WEC) Gold Medal award for its commitment to environmental sustainability.[165]

- On 19 April 2012, The Great Place to Work® Institute Canada mentioned Nestlé Canada Inc. as one of the '50 Best Large and Multinational Workplaces' in Canada (with more than 1,000 employees working in Canada and/or worldwide).[166]

- On 21 May 2012, Gartner published their annual Supply Chain Top 25, a list with global supply chain leaders. Nestlé ranks 18th in the list.[167]

- In September 2012, Nestlé was among the top-scoring companies on the Climate Disclosure Leadership Index (CDLI)

- In 2013, Nestlé retained its number one position in charity Oxfam's sustainability scorecard and improved its ratings on the issues of land, workers, and climate.[168]

- In 2014, Nestlé received the Henry Spira Corporate Progress Awards for altering its policies and practices to minimize adverse impacts on animals.[169]

- In March 2015, Nestlé ranked second in Oxfam's Behind the Brands scorecard, where the NGO ranks the world's 'Big 10' consumer food and beverage companies on their policies and commitments to improve food security and sustainability. Nestlé assumed the number one ranking for land rights while the company also outperformed its peers on transparency and water.[170]

Pronunciation

Nestlé is pronounced (French pronunciation: [nɛsle]; English: /ˈnɛsleɪ/, /ˈnɛsəl/, /ˈnɛsli/, formerly: /ˈnɛslz/).

Bibliography

- La stratégie Nestlé (Nestlé Strategy), Helmut Maucher, French translation by Monique Thiollet, Maxima Ed., Paris, 1995,[171] ISBN 2840010720

See also

- Competitors

- PepsiCo

- Kraft Heinz

- Mondelez International

- Unilever

- Mars, Incorporated

- Sara Lee

- Cadbury

- Danone

- Ferrero SpA

Notes and references

- 1 2 "Management". Nestlé. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Annual Results 2016" (PDF). Nestlé. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Nestlé's Brabeck: We have a "huge advantage" over big pharma in creating medical foods", CNN Money, 1 April 2011

- ↑ "Nestlé: The unrepentant chocolatier", The Economist, 29 October 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2012

- ↑ Rowan, Claire (9 September 2015). "The world's top 100 food & beverage companies – 2015: Change is the new normal". Food Engineering. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ McGrath, Maggie (27 May 2016). "The World's Largest Food And Beverage Companies 2016: Chocolate, Beer And Soda Lead The List". Forbes. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ 2014 Fortune Global 500 listing. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ "The World's Biggest Public Companies". Forbes. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ "Nestlé: Tailoring products to local niches" CNN, 2 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Annual Results 2014" (PDF). Nestlé. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ↑ "Nestlé to Decide on L’Oreal in 2014, Chairman Brabeck Says". Bloomberg, 14 April 2011

- ↑ 'Other industries', A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 4 (1959), pp. 220–253. Retrieved 14 August 2010

- ↑ HPatrick (3 January 2016). "Swiss Chocolate Brands".

- ↑ Blakely, Joe (2003). "Oregon Places: The Nestlé Condensary in Bandon". Oregon Historical Quarterly. Oregon Historical Society. 104: 566–577. JSTOR 20615370.

- ↑ "The inside story of the Cadbury takeover". Financial Times.

- ↑ "Nestlé takes world ice cream lead". BBC News. 19 January 2006. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ↑ "Nestlé completes takeover of Novartis food unit – SWI swissinfo.ch". SWI – the international service of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation. 2 July 2007.

- ↑ "Nestlé to buy Gerber for $5.5B". CNN. 12 April 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ↑ "Novartis completes its business portfolio restructuring, divesting Gerber for USD 5.5 billion to Nestlé". Novartis. 12 April 2007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "Media releases". Novartis.com. 3 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ (Press release) Nestlé enters into strategic partnership with Belgian luxury chocolate maker Pierre Marcolini. Nestlé retrieved from it 23 March 2011.

- ↑ Thomasson, Emma (4 January 2010). "Novartis seeks to buy rest of Alcon for $39 billion". Reuters. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Campbell, Matthew; Gretler, Corinne. "Nestlé Wants to Sell You Both Sugary Snacks and Diabetes Pills". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ↑ "Nestlé to Buy 60% Stake in Hsu Fu Chi for .7 Billion". Bloomberg. 11 July 2011.

- ↑ "Nestlé to Acquire Pfizer Baby Food Unit for $11.9 Billion". Bloomberg, 23 April 2012

- ↑ "Mead Johnson looks tasty, but Abbott may have to pass".

- ↑ "Nestlé to buy Pfizer Nutrition for $11.85bn". NewStatesman. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Nestle Acquires Stake in "Brain Food" Company". LA Weekly. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "PE Deals for Weight Loss Brands Face Shifting Diet Demographics". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Nestlé buys Louisiana depression food firm". Nutra.

- ↑ "Nestlé Sells PowerBar Brand". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Nestlé Explores Sale of Frozen Food Unit Davigel". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Nestle invests more in skin care strategy with 10 research centers". Reuters.

- ↑ "Nestle Nestlé to Move U.S. Headquarters to Rosslyn". ArlNow.

- ↑ "Kit Kat sugar content to be cut by 10%, says Nestle". BBC News. 8 March 2017.

- ↑ "Shreddies are about to get a lot healthier". The Independent. 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ↑ "Nestle plans $20.8 billion share buyback amid Third Point pressure". Reuters. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- 1 2 Chaudhuri, Saabira; Blackstone, Brian (2017-06-27). "Nestlé Plans Share Buyback After Pressure From Third Point". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- ↑ Forbes list of world's top companies Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ MarketWatch page on Nestle S.A. ADS Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- 1 2 Jobs Nestlé, global info

- ↑ "The Global RepTrak 100: The World's Most Reputable Companies (2015)" (PDF). Reputation Institute. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "General Mills: Joint ventures".

- ↑ Reuters Editorial (6 January 2012). "Coke, Nestle part ways on tea in U.S., elsewhere". Reuters.

- ↑ "Nestlé plans chilled dairy improvement with Lactalis venture", Dairy Reporter, 16 December 2005.

- ↑ "Nestlé and Colgate-Palmolive bite into mouth market", BreakingNews.ie, 11 December 2003.

- ↑ "Nestlé, Indofood create culinary product JV". FoodNavigator-Asia.com. 28 February 2005.

- ↑ "Snow Brand times thawing with Nestlé joint venture", Food Navigator, 24 January 2001.

- ↑ http://www.nestle.com/aboutus/management/boardofdirectors Nestle Board

- ↑ Carla Rapoport, Nestle's Brand Building Machine, Fortune Magazine, 19 September 1994, retrieved 4 September 2016

- ↑ McDonald, Scott (22 September 2008). "Nearly 53,000 Chinese children sick from milk". Google. Associated Press.

- ↑ Macartney, Jane (22 September 2008). "China baby milk scandal spreads as sick toll rises to 13,000". The Times. London. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ↑ "China milk scandal claims victim outside mainland". USA Today. Associated Press. 20 September 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ↑ "Melamine found in Nestlé milk powders". ABC Local. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ↑ "How Nestlé finds clean milk in China". Businessweek. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ↑ "Nestlé Opens Food Safety Institute in Beijing". Food Product Design. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ↑ "Live worms found in Nestlé Cerelac baby food in Coimbatore". Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Fresh trouble for Nestlé, weevils and fungus found in baby food Cerelac". Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Live Larvae Allegedly Found in Nestlé's Milk Powder in Tamil Nadu, More Tests On". NDTV. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ Neuman, William (14 January 2010). "Sample of Nestlé Cookie Dough Has E. Coli Bacteria". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Beware! Eating 2 -Minute Maggi Noodles can ruin your Nervous System". news.biharprabha.com. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ↑ "Maggi Noodles Packets Recalled Across Uttar Pradesh, Say Food Inspectors: Report". NDTV. New Delhi, India. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Sushmi Dey (16 May 2015). "'Maggi' under regulatory scanner for lead, MSG beyond permissible limit". The Times of India. New Delhi, India. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ "Delhi govt bans sales of Maggi from its stores: Report". Times of India. New Delhi, India. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Future Group bans Maggi too: The two-minute death of a India's favourite noodle brand". FirstPost. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Nestle India stocks crash over Maggi". The Hindu. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ HT Correespondent. "North to south: 5 states ban two-minute Maggi noodles in a day". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ IANS (4 June 2015). "Gujarat bans Maggi noodles for 30 days". The Times of India. (The Times Group). Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ "Maggi row: Nestlé shares down 3 per cent". The Hindu. 4 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ "FSSAI orders recall of all nine variants of Maggi noodles from India". FirstPost. 5 June 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Nepal bans import, sale of Maggi noodles". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "UK launches Maggi tests for lead content". Economic Times. PTI. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ "Maggi noodles withdrawn in East African supermarket". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "India sues Nestlé for nearly $100m over food safety". aljazeera.com. Aljazeera. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Thomas, Shibu (13 August 2015). "Relief for Nestlé, Bombay HC sets aside food regulator's ban on Maggi". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. The Times of India. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "India court lifts government ban on Maggi noodles". aljazeera.com. Aljazeera. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "India court says Maggi noodle ban 'legally untenable'". bbc.com. BBC News. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Pendleton, Jennifer (23 November 1993) Rich deal for Disney, Nestlé", Variety

- ↑ "The Land". Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Nestlé continues sponsorship of the Beijing Music Festival", China.org, 6 August 2010

- ↑ "Nestlé extends Salzburg Festival partnership until 2015", Nestlé, 5 October 2011

- ↑ "Nestlé and Salzburg Festival Young Conductors Award 2015".

- ↑ "Nestlé confirms sponsorship renewal of Tour de France". FoodBev. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "UK: Nestle Waters secures Tour de France tie-up for Buxton Natural Mineral Water".

- ↑ "UK: Nestlé Rowntree to sponsor Women's Rugby League team".

- ↑ "IAAF, Nestlé becomes main sponsor of worldwide IAAF Kids' Athletics", 27 January 2012

- ↑ Reinsch, Michael (10 February 2016). Leichtathletik-Weltverband „toxisch“ (in German). Frankfurter Allgemeine Sport. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ "Nestlé and AIS Sports Nutrition". Australian Government.

- ↑ "Baby Milk Action - Protecting breastfeeding - Protecting babies fed on formula".

- ↑ "A History of Breastfeeding".

- ↑ "Nestle boycott being suspended". The New York Times. 27 January 1984. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ ANDREW BROWN (23 October 2011). "Synod votes to end Nestle boycott after passionate debate". The Independent.

- ↑ "LISTSERV 16.0 - LACTNET Archives".

- ↑ and http://revolution.allbest.ru/marketing/00250283_0.html http://wayback.archive.org/web/20160103032603/https://prezi.com/y_dtv6kzkd92/Nestle/

- ↑ http://eastclevelandurc.org.uk/Group%20NewsFeb12.PDF

- ↑ http://www.ftse.com/products/downloads/FTSE_Letter_to_Nestle.pdf

- ↑ http://www.ftse.com/products/downloads/PwC_F4G_BMS_Assessment_Report_2012.pdf

- ↑ http://www.Nestle.com/csv/nutrition/baby-milk/compliance-record

- ↑ "Letter from NGOs to Nestlé" (PDF). Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ↑ "The "LAOS: NGOs flay Nestlé’s infant formula strategy". Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ "Nestlé independent assurance statement" (PDF).

- ↑ Bernstein, Adam. "Ernest W. Lefever dies at 89; founder of conservative public policy organization", Los Angeles Times, 31 July 2009. Accessed 3 August 2009.

- 1 2 "为争“第一口奶”市场,雀巢中国6名员工非法获取公民信息 (To capture infant formula market, six Nestlé China employees gained illegal access to citizen information)". Caijing.com.cn.

- ↑ Harney, Alexandra. "Special Report: How Big Formula bought China". Reuters.com.

- ↑ Muir, Paul (28 November 2013). "The human rights and wrongs of Nestlé and water for all". The National. Abu Dhabi. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ Confino, Jo (2013-02-04). "Nestlé's Peter Brabeck: our attitude towards water needs to change". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ↑ Denny, Charlotte (20 December 2002). "Retreat by Nestlé on Ethiopia's $6m debt". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ↑ "Nestlé receives compensation from Ethiopia". Swiss Info. 24 October 2003.

- ↑ Dworkin, Tex (12 February 2007). "Delicious idea: End child slavery by eating chocolate". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ "On Halloween, Nestlé Claims no Responsiblity [sic] for Child Labor". International Labor Rights Forum. 30 October 2006. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ "Amicus Brief in Doe v. Nestlé". EarthRights International. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ Wilber Jaramillo, Gwendolyn (19 September 2010). "Second Circuit Holds that Corporations are not Proper Defendants under the Alien Tort Statute". Foley and Hoag LLP. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ (PDF) http://cdn.ca9.uscourts.gov/datastore/opinions/2014/09/04/10-56739.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Kendall, Brent (11 January 2016). "Supreme Court Denies Nestle, Cargill, ADM Appeal in Slave Labor Case". Retrieved 1 February 2017 – via Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Romano, U. Roberto & Mistrati, Miki (Directors) (16 March 2010). The Dark Side of Chocolate (Television Production). Bastard Films. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- 1 2 Raghavan, Sudarsan; Chatterjee, Sumana (24 June 2001). "Slaves feed world's taste for chocolate: Captives common in cocoa farms of Africa". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ "Combating Child Labour in Cocoa Growing" (PDF). International Labour Organization. 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Wolfe, David; Shazzie (2005). Naked Chocolate: The Astonishing Truth about the World's Greatest Food. North Atlantic Books. p. 98. ISBN 1556437315. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ↑ Hawksley, Humphrey (12 April 2001). "Mali's children in chocolate slavery". BBC News. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ↑ Hawksley, Humphrey (4 May 2001). "Ivory Coast accuses chocolate companies". BBC News. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ↑ "2014 Assessments of Shared Hazelnut Supply Chain In Turkey: Nestlé, Balsu, and Olam | Fair Labor Association". www.fairlabor.org. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Gray, Jeff (5 December 2012). "Former Nestlé Canada CEO may face chocolate price-fixing charge ‘shortly’". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- 1 2 3 "Nestlé bottled-water ads misleading, environmentalists say". CBC News. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Groups Challenge Nestlé’s Bottled Water Greenwashing". Polaris Institute. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- 1 2 Anderson, Scott (1 December 2008). "Nestlé water ads misleading: Canada green groups". Reuters. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- 1 2 Dejong, Michael (24 March 2009). "Water, Water Everywhere". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Little oversight as Nestlé taps Morongo reservation water, The Desert Sun. 12 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Associated Press (11 April 2015). "US Forest Service investigates expired Nestlé water permit". The Washington Times. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ James, Ian (8 March 2015). "Bottling water without scrutiny". The Desert Sun. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- 1 2 Bernish, Claire (13 August 2015). "Forest Service Official Who Let Nestlé Drain California Water Now Works for Them". theanitmedia. The Anti Media. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "California Water Management". Nestleusa.com. Nestlé. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "Arrowhead Honored at Southern California Mountains Foundation". Nestle-watersna.com. Nestlé Waters North America. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ Tracy Loew (23 April 2015). "Oregon legislators protest Nestlé water deal". Statesman Journal. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Alison Vekshin (26 May 2015). "Nestlé Bottled-Water Plan Draws Fight in Drought-Stricken Oregon". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Bottled Water and the Drought: The Center of Debate over Water Policy in Oregon and California Hydrowonk Blog. An Open Intellectual Marketplace for the Water Industry.Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ На канал Ахметова не взяли україномовну ведучу (in Ukrainian). depo. 14 August 2015

- ↑ На украинский канал не взяли ведущую, потому что она не говорит по-русски (in Russian). Dusya. Telekrytyka. 13 August 2015

- ↑ У Києві чоловік у масці кролика з автоматом протестував проти русифікації телепростору (in Ukrainian). zik. 19 August 2015

- ↑ Nestlé - спонсор русифікації України (in Ukrainian). Vidsich. 10 September 2015

- 1 2 "Nestle confirms labor abuse among its Thai seafood suppliers". The Big Story. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ Reuters Editorial (24 November 2015). "Campaigners hope others follow Nestle in admitting and acting on slave labour in its products". Reuters.

- ↑ "Nestlé Reports on Abuses in Thailand’s Seafood Industry". The New York Times. 24 November 2015.

- ↑ "History & Mission". World Cocoa Foundation. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- 1 2 "SAI Platform – Who we are". Sustainable Agriculture Initiative Platform. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ Petr Matous (2015) Social networks and environmental management at multiple levels: soil conservation in Sumatra. Ecology and Society 20(3):37.

- ↑ Reuters Editorial (22 March 2011). "Nestle head emphasizes profiting from doing good". Reuters.

- ↑ "6 steps to create shared value in your company". GreenBiz. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Global Shared Value Prize on Offer".

- ↑ "Entries open for CHF 500k Nestlé Creating Shared Value Prize". UK Fundraising. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- 1 2 "What does the 'Cocoa Plan' label on chocolate mean?". MNN - Mother Nature Network. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "The Rainforest Alliance and Nestlé Nespresso Announce Advances in Quest for Sustainable Quality Coffee", Rain Forest Alliance, 22 June 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2012

- ↑ "Rainforest Alliance".

- ↑ "Nestlé to Expand Business in Health Care Nutrition", New York Times, Matthew Saltmarsh, 27 September 2010

- ↑ "Nestlé Joins Fair Labor Association, FLA, 1 March 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012".

- ↑ "Nestle Joins Fair Labor Association".

- ↑ "Women's Rights: Nestlé on female cocoa farmers". ConfectioneryNews.com.

- ↑ "How the Global Food Sector Can Solve Our Food Security Crisis". Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "IFRC and Nestlé renew partnership to support water and sanitation programmes".

- ↑ "Nestlé Targets Worldwide Registration of All Plants to ISO 14001, OHSAS 18001", Quality Digest, 24 March 2010

- ↑ "Nestlé Purina Receives Malcolm Baldrige Award", Supermarket News, 15 December 2010

- ↑ "Providing Context to the 2012 Nestlé FTSE4Good BMS Verification"

- ↑ "Top 20 Worlds’ Best Employers", 7 October 2011 Archived 31 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Nestlé best employer in Switzerland: survey", The Local, 13 December 2011

- ↑ "Nestlé wins global food industry award" http://wayback.archive.org/web/20160103032603/http://www.csreurope.org/news.php?type=&action=show_news&news_id=3646, CSR Europe, 24 August 2010

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 2012-05-18."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ↑ 2012 "Best Workplaces in Canada (over 1000 employees)", GreatPlaceToWork, 19 April 2012

- ↑ "The Gartner Supply Chain Top 25 for 2012", Gartner Group, 21 May 2012

- ↑ "Supply Chain Top 25".

- ↑ "2014 Spira Award Winners – Wayne Pacelle's Blog". A Humane Nation. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Company Scorecard". Behind the Brands. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Catalogue collectif". Retrieved 10 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nestlé. |

.svg.png)