Nepalese scripts

| Nepalese scripts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Nepal Bhasa |

Parent systems | |

The Nepalese scripts are alphabetic writing systems of Nepal. They have been used primarily to write both the national Indo-European language of Nepali plus some Tibeto-Burman languages such as Newari (also known locally as Nepal Bhasa).[1][2]

The older alphabets, known as Brahmic scripts, were in widespread use from the 10th to the early 20th-century A.C.E., but have since been largely supplanted by the modern script known as Devanagari. Of the older scripts, about 50,000 manuscripts written in Nepal Lipi have been archived.[3]

Outside of Nepal, Brahmi scripts also have been used to write Sanskrit, Hindi, Maithili, Bengali and Braj Bhasha languages.[4][5] They have reportedly been used to inscribe mantras on funerary markers as distant as Japan as well.[6]

Early history

Nepal or Nepalese script[7] appeared in the 10th century. The earliest instance is a manuscript entitled Lankavatara Sutra dated Nepal Era 28 (908 AD). Another early specimen is a palm-leaf manuscript of a Buddhist text the Prajnaparamita, dated Nepal Era 40 (920 AD).[8] One of the oldest manuscript of Ramayana, preserved till date, was written in Nepal Script in 1041.[9]

The script has been used on stone and copper plate inscriptions, coins (Nepalese mohar), palm-leaf documents and Hindu and Buddhist manuscripts.[10][11]

Among the different scripts based on Nepal script, Ranjana (meaning "delightful"), Bhujinmol ("fly-headed") and Prachalit ("ordinary") are the most common.[12][13]

Ranjana is the most ornate among the scripts. It is most commonly used to write Buddhist texts and inscribe mantras on prayer wheels, shrines, temples, and monasteries. The popular Buddhist mantra Om mani padme hum (meaning ("Hail to the jewel in the lotus" in Sanskrit) is often written in Ranjana.

Besides the Kathmandu Valley and the Himalayan region in Nepal, the Ranjana script is used for sacred purposes in Tibet, China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Bhutan, Sikkim and Ladakh.[14]

The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, Tibet is ornamented with mantras embossed in Ranjana script, and the panels under the eaves are numbered using Nepal Lipi.[15]

Among the famed historical texts written in Nepal Lipi are Gopalarajavamsavali, a history of Nepal, which appeared in 1389 AD,[16] the Nepal-Tibet treaty of Nepal Era 895 (1775 AD) and a letter dated Nepal Era 535 (1415 AD) sent by Chinese Emperor Tai Ming to Shakti-simha-rama, a feudatory of Banepa.[17][18]

Types

The different scripts derived from Nepal script are as follows:[19]

- Ranjana script

- Bhujimol

- Kunmol script

- Kwenmol script

- Golmol script

- Pachumol script

- Hinmol script

- Litumol script

- Prachalit Nepal script

Decline

Nepalese scripts saw a widespread use for a thousand years in Nepal. In 1906, the Rana regime banned Nepal Bhasa, Nepal Era and Nepal Lipi from official use as part of its policy to subdue them, and the script fell into decline.

Authors were also encouraged to switch to Devanagari to write Nepal Bhasa because of the availability of moveable type for printing, and Nepal Lipi was pushed further into the background.[20] However, the script continued to be used for religious and ceremonial purposes till the 1950s.

Revival

After the Rana dynasty was overthrown and democracy established in 1951,[21] restrictions on Nepal Bhasa were lifted. Attempts were made to study and revive the old scripts,[22] and alphabet books were published. Hemraj Shakyavamsha published an alphabet book of 15 types of Nepalese alphabets including Ranjana, Bhujimol and Pachumol.[23]

In 1952, a pressman Pushpa Ratna Sagar of Kathmandu had moveable type of Nepal script made in India. The metal type was used to print the dateline and the titles of the articles in Thaunkanhe monthly.[24]

In 1989, the first book to be printed using a computer typeface of Nepal script, Prasiddha Bajracharyapinigu Sanchhipta Bibaran ("Profiles of Renowned Bajracharyas") by Badri Ratna Bajracharya, was published.

Today, Nepal Lipi has gone out of general usage, but it is sometimes used in signage, invitation and greeting cards, letterheads, book and CD covers, product labels and the mastheads of newspapers. A number of private organizations are engaged in its study and promotion.

Nepal Lipi (with the name “Newa”) was approved for inclusion in Unicode 9.0.

Gallery

Invitation card.

Invitation card. Thaunkanhe monthly.

Thaunkanhe monthly. Sandhya Times daily.

Sandhya Times daily. Copper inscription from 1952 AD.

Copper inscription from 1952 AD. Stone inscription from 1654 AD.

Stone inscription from 1654 AD. Embossed lettering from 1877 AD.

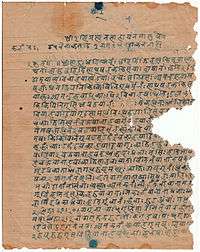

Embossed lettering from 1877 AD. Sanskrit Buddhist manuscript in Nepal script from 1869 AD.

Sanskrit Buddhist manuscript in Nepal script from 1869 AD. Table of Prachalit Nepal script.

Table of Prachalit Nepal script.

See also

References

- ↑ Lienhard, Siegfried (1984). Songs of Nepal. Hawaii: Center for Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press. pp. 2, 14. ISBN 0-8248-0680-8. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ↑ Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Page 306.

- ↑ Nepal-German Manuscript Cataloguing Project

- ↑ "Writing systems that use this script". Scriptsource. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Pokharel, Balkrishna (1975). Panchsay Barsha. Kathmandu: Sajha Prakashan. Pages 84 and 96.

- ↑ LeVine, Sarah; Gellner, David N. (2005). Rebuilding Buddhism: The Theravada Movement in Twentieth-Century Nepal. Harvard University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-674-01908-9.

- ↑ Sakya, Hemaraj (2004) Svayambhū Mahācaitya: The self-arisen great Caitya of Nepal. Svayambhu Vikash Mandal. ISBN 99933-864-0-5, ISBN 978-99933-864-0-7. Page 607. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ Shrestha, Rebati Ramanananda (2001). Newah. Lalitpur: Sahityaya Mulukha. Page 86.

- ↑ Institute of Scientific Research on Vedas

- ↑ Bendall, Cecil (1883). Catalogue of the Buddhist Sanskrit Manuscripts in the University Library, Cambridge. Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 301. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Nepalese Inscriptions in the Rubin Collection". Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ↑ Lienhard, Siegfried (1984). Songs of Nepal. Hawaii: Center for Asian and Pacific Studies, University of Hawaii, University of Hawaii Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-8248-0680-8. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ↑ Shrestha, Bal Gopal (January 1999). "The Newars: The Indigenous Population of the Kathmandu Valley in the Modern State of Nepal)" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Retrieved 23 March 2012. Page 87.

- ↑ "Ranjana Alphabet". Lipi Thapu Guthi. 1995.

- ↑ Tuladhar, Kamal Ratna (second edition 2011). Caravan to Lhasa: A Merchant of Kathmandu in Traditional Tibet. Kathmandu: Lijala and Tisa. ISBN 99946-58-91-3. Page 115.

- ↑ Vajracarya, Dhanavajra and Malla, Kamal P. (1985). The Gopalarajavamsavali. Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH.

- ↑ Tamot, Kashinath (2009). Sankhadharkrit Nepal Sambat. Nepal Mandala Research Guthi. ISBN 978-9937209441. Pages 68-69.

- ↑ Rolamba. April–June 1983. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Shakyavansha, Hemraj (1993, eighth edition). Nepalese Alphabet. Kathmandu: Mandas Lumanti Prakashan.

- ↑ Tuladhar, Prem Shanti (2000). Nepal Bhasa Sahityaya Itihas: The History of Nepalbhasa Literature. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. ISBN 99933-56-00-X. Page 14.

- ↑ Brown, T. Louise (1996). The Challenge to Democracy in Nepal: A Political History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08576-4, ISBN 978-0-415-08576-2. Page 21.

- ↑ Sada, Ivan (March 2006). "Interview: Hem Raj Shakya". ECS Nepal. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Nepal Lipi Sangraha" (PDF). Gorkhapatra. 20 April 1953. Retrieved 7 May 2012. Page 3.

- ↑ Tuladhar, Kamal Ratna (22 March 2009). "A man of letters". The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 23 February 2012.