Breathing gas

A breathing gas is a mixture of gaseous chemical elements and compounds used for respiration. Air is the most common, and only natural, breathing gas. But other mixtures of gases, or pure gases, are also used in breathing equipment and enclosed habitats such as scuba equipment, surface supplied diving equipment, recompression chambers, submarines, space suits, spacecraft, medical life support and first aid equipment, high-altitude mountaineering and anaesthetic machines.[1][2][3]

Oxygen is the essential component for any breathing gas, at a partial pressure of between roughly 0.16 and 1.60 bar at the ambient pressure. The oxygen is usually the only metabolically active component unless the gas is an anaesthetic mixture. Some of the oxygen in the breathing gas is consumed by the metabolic processes, and the inert components are unchanged, and serve mainly to dilute the oxygen to an appropriate concentration, and are therefore also known as diluent gases. Most breathing gases therefore are a mixture of oxygen and one or more inert gases.[1][3] Other breathing gases have been developed to improve on the performance of ordinary air by reducing the risk of decompression sickness, reducing the duration of decompression stops, reducing nitrogen narcosis or allowing safer deep diving.[1][3]

A safe breathing gas for hyperbaric use has three essential features:

- it must contain sufficient oxygen to support life, consciousness and work rate of the breather.[1][2][3]

- it must not contain harmful gases. Carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide are common poisons which may contaminate breathing gases. There are many other possibilities.[1][2][3]

- it must not become toxic when being breathed at high pressure such as when underwater. Oxygen and nitrogen are examples of gases that become toxic under pressure.[1][2][3]

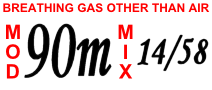

The techniques used to fill diving cylinders with gases other than air are called gas blending.[4][5]

Breathing gases for use at ambient pressures below normal atmospheric pressure are usually air enriched with oxygen to provide sufficient oxygen to maintain life and consciousness, or to allow higher levels of exertion than would be possible using air. It is common to provide the additional oxygen as a pure gas added to the breathing air at inhalation, or though a life-support system.

Breathing gases for diving and other hyperbaric use

These common diving breathing gases are used:

- Air is a mixture of 21% oxygen, 78% nitrogen, and approximately 1% other trace gases, primarily argon; to simplify calculations this last 1% is usually treated as if it were nitrogen. Being cheap and simple to use, it is the most common diving gas.[1][2][3] As its nitrogen component causes nitrogen narcosis, it is considered to have a safe depth limit of about 40 metres (130 feet) for most divers, although the maximum operating depth of air is 66.2 metres (218 feet).[1][3][6]

- Pure oxygen is mainly used to speed the shallow decompression stops at the end of a military, commercial, or technical dive and is only safe down to a depth of 6 meters (maximum operating depth) before oxygen toxicity sets in.[1][2][3][6] It was much used in frogmen's rebreathers.[2][6][7][8]

- Nitrox is a mixture of oxygen and air, and generally refers to mixtures which are more than 21% oxygen. It can be used as a tool to accelerate in-water decompression stops or to decrease the risk of decompression sickness and thus prolong a dive (a common misconception is that the diver can go deeper, this is not true owing to a shallower maximum operating depth than on conventional air).[1][2][3][9]

- Trimix is a mixture of oxygen, nitrogen and helium and is often used at depth in technical diving and commercial diving instead of air to reduce nitrogen narcosis and to avoid the dangers of oxygen toxicity.[1][2][3]

- Heliox is a mixture of oxygen and helium and is often used in the deep phase of a commercial deep dive to eliminate nitrogen narcosis.[1][2][3][10]

- Heliair is a form of trimix that is easily blended from helium and air without using pure oxygen. It always has a 21:79 ratio of oxygen to nitrogen; the balance of the mix is helium.[3][11]

- Hydreliox is a mixture of oxygen, helium, and hydrogen and is used for dives below 130 metres in commercial diving.[1][3][10][12][13]

- Hydrox, a gas mixture of hydrogen and oxygen, is used as a breathing gas in very deep diving.[1][3][10][12][14]

- Neox (also called neonox) is a mixture of oxygen and neon sometimes employed in deep commercial diving. It is rarely used due to its cost. Also, DCS symptoms produced by neon ("neox bends") have a poor reputation, being widely reported to be more severe than those produced by an exactly equivalent dive-table and mix with helium.[1][3][10][15]

| Gas | Symbol | Typical shoulder colours | Cylinder shoulder | Quad upper frame/ frame valve end |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical oxygen | O2 |  |

White | White |

| Oxygen and helium mixtures (Heliox) |

O2/He |   |

Brown and white quarters or bands |

Brown and white short (8 inches (20 cm)) alternating bands |

| Oxygen, helium and nitrogen mixtures (Trimix) |

O2/He/N2 |   |

Black, white and brown quarters or bands |

Black, white and brown short (8 inches (20 cm)) alternating bands |

| Oxygen and nitrogen mixtures (Nitrox) including air |

N2/O2 |   |

Black and white quarters or bands |

Black and white short (8 inches (20 cm)) alternating bands |

Individual component gases

Breathing gases for diving are mixed from a small number of component gases which provide special characteristics to the mixture which are not available from atmospheric air.

Oxygen

Oxygen (O2) must be present in every breathing gas.[1][2][3] This is because it is essential to the human body's metabolic process, which sustains life. The human body cannot store oxygen for later use as it does with food. If the body is deprived of oxygen for more than a few minutes, unconsciousness and death result. The tissues and organs within the body (notably the heart and brain) are damaged if deprived of oxygen for much longer than four minutes.

Filling a diving cylinder with pure oxygen costs around five times more than filling it with compressed air. As oxygen supports combustion and causes rust in diving cylinders, it should be handled with caution when gas blending.[4][5]

Oxygen has historically been obtained by fractional distillation of liquid air, but is increasingly obtained by non-cryogenic technologies such as pressure swing adsorption (PSA) and vacuum swing adsorption (VSA) technologies.[17]

The fraction of the oxygen component of a breathing gas mixture is sometimes used when naming the mix:

- hypoxic mixes, strictly, contain less than 21% oxygen, although often a boundary of 16% is used, and are designed only to be breathed at depth as a "bottom gas" where the higher pressure increases the partial pressure of oxygen to a safe level.[1][2][3] Trimix, Heliox and Heliair are gas blends commonly used for hypoxic mixes and are used in professional and technical diving as deep breathing gases.[1][3]

- normoxic mixes have the same proportion of oxygen as air, 21%.[1][3] The maximum operating depth of a normoxic mix could be as shallow as 47 metres (155 feet). Trimix with between 17% and 21% oxygen is often described as normoxic because it contains a high enough proportion of oxygen to be safe to breathe at the surface.

- hyperoxic mixes have more than 21% oxygen. Enriched Air Nitrox (EANx) is a typical hyperoxic breathing gas.[1][3][9] Hyperoxic mixtures, when compared to air, cause oxygen toxicity at shallower depths but can be used to shorten decompression stops by drawing dissolved inert gases out of the body more quickly.[6][9]

The fraction of the oxygen determines the greatest depth at which the mixture can safely be used to avoid oxygen toxicity. This depth is called the maximum operating depth.[1][3][6][9]

The concentration of oxygen in a gas mix depends on the fraction and the pressure of the mixture. It is expressed by the partial pressure of oxygen (ppO2).[1][3][6][9]

The partial pressure of any component gas in a mixture is calculated as:

- partial pressure = total absolute pressure × volume fraction of gas component

For the oxygen component,

- ppO2 = P × FO2

where:

- ppO2 = partial pressure of oxygen

- P = total pressure

- FO2 = volume fraction of oxygen content

The minimum safe partial pressure of oxygen in a breathing gas is commonly held to be 16 kPa (0.16 bar). Below this partial pressure the diver may be at risk of unconsciousness and death due to hypoxia, depending on factors including individual physiology and level of exertion. When a hypoxic mix is breathed in shallow water it may not have a high enough ppO2 to keep the diver conscious. For this reason normoxic or hyperoxic "travel gases" are used at medium depth between the "bottom" and "decompression" phases of the dive.

The maximum safe ppO2 in a breathing gas depends on exposure time, the level of exercise and the security of the breathing equipment being used. It is typically between 100 kPa (1 bar) and 160 kPa (1.6 bar); for dives of less than three hours it is commonly considered to be 140 kPa (1.4 bar), although the U.S. Navy has been known to authorize dives with a ppO2 of as much as 180 kPa (1.8 bar).[1][2][3][6][9] At high ppO2 or longer exposures, the diver risks oxygen toxicity which may result in a seizure.[1][2] Each breathing gas has a maximum operating depth that is determined by its oxygen content.[1][2][3][6][9] For therapeutic recompression and hyperbaric oxygen therapy partial pressures of 2.8 bar are commonly used in the chamber, but there is no risk of drowning if the occupant loses consciousness.[2]

Oxygen analysers are used to measure the ppO2 in the gas mix.[4]

Divox is breathing grade oxygen labelled for diving use. In the Netherlands, pure oxygen for breathing purposes is regarded as medicinal as opposed to industrial oxygen, such as that used in welding, and is only available on medical prescription. The diving industry registered Divox as a trademark for breathing grade oxygen to circumvent the strict rules concerning medicinal oxygen thus making it easier for (recreational) scuba divers to obtain oxygen for blending their breathing gas. In most countries, there is no difference in purity in medical oxygen and industrial oxygen, as they are produced by exactly the same methods and manufacturers, but labeled and filled differently. The chief difference between them is that the record-keeping trail is much more extensive for medical oxygen, to more easily identify the exact manufacturing trail of a "lot" or batch of oxygen, in case problems with its purity are discovered. Aviation grade oxygen is similar to medical oxygen, but may have a lower moisture content.[4]

Nitrogen

Nitrogen (N2) is a diatomic gas and the main component of air, the cheapest and most common breathing gas used for diving. It causes nitrogen narcosis in the diver, so its use is limited to shallower dives. Nitrogen can cause decompression sickness.[1][2][3][18]

Equivalent air depth is used to estimate the decompression requirements of a nitrox (oxygen/nitrogen) mixture. Equivalent narcotic depth is used to estimate the narcotic potency of trimix (oxygen/helium/nitrogen mixture). Many divers find that the level of narcosis caused by a 30 m (100 ft) dive, whilst breathing air, is a comfortable maximum.[1][2][3][19][20]

Nitrogen in a gas mix is almost always obtained by adding air to the mix.

Helium

Helium (He) is an inert gas that is less narcotic than nitrogen at equivalent pressure (in fact there is no evidence for any narcosis from helium at all), so it is more suitable for deeper dives than nitrogen.[1][3] Helium is equally able to cause decompression sickness. At high pressures, helium also causes high-pressure nervous syndrome, which is a CNS irritation syndrome which is in some ways opposite to narcosis.[1][2][3][21]

Helium mixture fills are considerably more expensive than air fills due to the cost of helium and the cost of mixing and compressing the mix.

Helium is not suitable for dry suit inflation owing to its poor thermal insulation properties – compared to air, which is regarded as a reasonable insulator, helium has six times the thermal conductivity.[22] Helium's low molecular weight (monatomic MW=4, compared with diatomic nitrogen MW=28) increases the timbre of the breather's voice, which may impede communication.[1][3][23] This is because the speed of sound is faster in a lower molecular weight gas, which increases the resonance frequency of the vocal cords.[1][23] Helium leaks from damaged or faulty valves more readily than other gases because atoms of helium are smaller allowing them to pass through smaller gaps in seals.

Helium is found in significant amounts only in natural gas, from which it is extracted at low temperatures by fractional distillation.

Neon

Neon (Ne) is an inert gas sometimes used in deep commercial diving but is very expensive.[1][3][10][15] Like helium, it is less narcotic than nitrogen, but unlike helium, it does not distort the diver's voice.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen (H2) has been used in deep diving gas mixes but is very explosive when mixed with more than about 4 to 5% oxygen (such as the oxygen found in breathing gas).[1][3][10][12] This limits use of hydrogen to deep dives and imposes complicated protocols to ensure that excess oxygen is cleared from the breathing equipment before breathing hydrogen starts. Like helium, it raises the timbre of the diver's voice. The hydrogen-oxygen mix when used as a diving gas is sometimes referred to as Hydrox. Mixtures containing both hydrogen and helium as diluents are termed Hydreliox.

Unwelcome components of breathing gases for diving

Many gases are not suitable for use in diving breathing gases.[5][24] Here is an incomplete list of gases commonly present in a diving environment:

Argon

Argon (Ar) is an inert gas that is more narcotic than nitrogen, so is not generally suitable as a diving breathing gas.[25] Argox is used for decompression research.[1][3][26][27] It is sometimes used for dry suit inflation by divers whose primary breathing gas is helium-based, because of argon's good thermal insulation properties. Argon is more expensive than air or oxygen, but considerably less expensive than helium. Argon is a component of natural air, and constitutes 0.934% by volume of the Earth's atmosphere.[28]

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced by the metabolism in the human body and can cause carbon dioxide poisoning.[24][29][30] When breathing gas is recycled in a rebreather or life support system, the carbon dioxide is removed by scrubbers before the gas is re-used.

Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (CO) is produced by incomplete combustion.[1][2][5][24] See carbon monoxide poisoning. Four common sources are:

- Internal combustion engine exhaust gas containing CO in the air being drawn into a diving air compressor. CO in the intake air cannot be stopped by any filter. The exhausts of all internal combustion engines running on petroleum fuels contain some CO, and this is a particular problem on boats, where the intake of the compressor cannot be arbitrarily moved as far as desired from the engine and compressor exhausts.

- Heating of lubricants inside the compressor may vaporize them sufficiently to be available to a compressor intake or intake system line.

- In some cases hydrocarbon lubricating oil may be drawn into the compressor's cylinder directly through damaged or worn seals, and the oil may (and usually will) then undergo combustion, being ignited by the immense compression ratio and subsequent temperature rise. Since heavy oils don't burn well - especially when not atomized properly - incomplete combustion will result in carbon monoxide production.

- A similar process is thought to potentially happen to any particulate material, which contains "organic" (carbon-containing) matter, especially in cylinders which are used for hyperoxic gas mixtures. If the compressor air filter(s) fail, ordinary dust will be introduced to the cylinder, which contains organic matter (since it usually contains humus). A more severe danger is that air particulates on boats and industrial areas, where cylinders are filled, often contain carbon-particulate combustion products (these are what makes a dirt rag black), and these represent a more severe CO danger when introduced into a cylinder.

Carbon monoxide is generally avoided as far as is reasonably practicable by positioning of the air intake in uncontaminated air, filtration of particulates from the intake air, use of suitable compressor design and appropriate lubricants, and ensuring that running temperatures are not excessive. Where the residual risk is excessive, a hopcalite catalyst can be used in the high pressure filter to convert carbon monoxide into carbon dioxide, which is far less toxic.

Hydrocarbons

Hydrocarbons (CxHy) are present in compressor lubricants and fuels. They can enter diving cylinders as a result of contamination, leaks, or due to incomplete combustion near the air intake.[2][4][5][24][31]

- They can act as a fuel in combustion increasing the risk of explosion, especially in high-oxygen gas mixtures.

- Inhaling oil mist can damage the lungs and ultimately cause the lungs to degenerate with severe lipid pneumonia[32] or emphysema.

Moisture content

The process of compressing gas into a diving cylinder removes moisture from the gas.[5][24] This is good for corrosion prevention in the cylinder but means that the diver inhales very dry gas. The dry gas extracts moisture from the diver's lungs while underwater contributing to dehydration, which is also thought to be a predisposing risk factor of decompression sickness. It is also uncomfortable, causing a dry mouth and throat and making the diver thirsty. This problem is reduced in rebreathers because the soda lime reaction, which removes carbon dioxide, also puts moisture back into the breathing gas.[8] In hot climates, open circuit diving can accelerate heat exhaustion because of dehydration. Another concern with regard to moisture content is the tendency of moisture to condense as the gas is decompressed while passing through the regulator; this coupled with the extreme reduction in temperature, also due to the decompression can cause the moisture to solidify as ice. This icing up in a regulator can cause moving parts to seize and the regulator to fail or free flow. This is one of the reasons that scuba regulators are generally constructed from brass, and chrome plated (for protection). Brass, with its good thermal conductive properties, quickly conducts heat from the surrounding water to the cold, newly decompressed air, helping to prevent icing up.

Gas detection and measurement

It is difficult to detect most gases that are likely to be present in diving cylinders because they are colourless, odourless and tasteless. Electronic sensors exist for some gases, such as oxygen analysers, helium analyser, carbon monoxide detectors and carbon dioxide detectors.[2][4][5] Oxygen analysers are commonly found underwater in rebreathers.[8] Oxygen and helium analysers are often used on the surface during gas blending to determine the percentage of oxygen or helium in a breathing gas mix.[4] Chemical and other types of gas detection methods are not often used in recreational diving, but are used for periodical quality testing of compressed breathing air from diving air compressors.[4]

Diving gas blending

Gas blending (or Gas mixing) of breathing gases for diving is the filling of gas cylinders with non-air breathing gases.

Filling cylinders with a mixture of gases has dangers for both the filler and the diver. During filling there is a risk of fire due to use of oxygen and a risk of explosion due to the use of high-pressure gases. The composition of the mix must be safe for the depth and duration of the planned dive. If the concentration of oxygen is too lean the diver may lose consciousness due to hypoxia and if it is too rich the diver may suffer oxygen toxicity. The concentration of inert gases, such as nitrogen and helium, are planned and checked to avoid nitrogen narcosis and decompression sickness.

Methods used include batch mixing by partial pressure or by mass fraction, and continuous blending processes. Completed blends are analysed for composition for the safety of the user. Gas blenders may be required by legislation to prove competence if filling for other persons.

Hypobaric breathing gases

Breathing gases for use at reduced ambient pressure are used for high altitude flight in unpressurised aircraft, in space flight, particularly in space suits, and for high altitude mountaineering. In all these cases, the primary consideration is providing an adequate partial pressure of oxygen. In some cases the breathing gas has oxygen added to make up a sufficient concentration, and in other cases the breathing gas may be pure or nearly pure oxygen. Closed circuit systems may be used to conserve the breathing gas, which may be in limited supply - in the case of mountaineering the user must carry the supplemental oxygen, and in space flight the cost of lifting mass into orbit is very high.

Medical breathing gases

Medical use of breathing gases other than air include oxygen therapy and anesthesia applications.

Oxygen therapy

Oxygen therapy, also known as supplemental oxygen, is the use of oxygen as a medical treatment.[33] This can include for low blood oxygen, carbon monoxide toxicity, cluster headaches, and to maintain enough oxygen while inhaled anesthetics are given.[34] Long term oxygen is often useful in people with chronically low oxygen such as from severe COPD or cystic fibrosis.[35][33] Oxygen can be given in a number of ways including nasal cannula, face mask, and inside a hyperbaric chamber.[36][37]

High concentrations of oxygen can cause oxygen toxicity such as lung damage or result in respiratory failure in those who are predisposed.[34][38] It can also dry out the nose and increase the risk of fires in those who smoke. The target oxygen saturation recommended depends on the condition being treated. In most conditions a saturation of 94-98% is recommended, while in those at risk of carbon dioxide retention saturations of 88-92% are preferred, and in those with carbon monoxide toxicity or cardiac arrest they should be as high as possible.[33] Air is typically 21% oxygen by volume.[38] Oxygen is required by people for proper cell metabolism.[39]

The use of oxygen in medicine become common around 1917.[40][41] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[42] The cost of home oxygen is about 150 USD a month in Brazil and 400 USD a month in the United States.[35] Home oxygen can be provided either by oxygen tanks or an oxygen concentrator.[33] Oxygen is believed to be the most common treatment given in hospitals in the developed world.[43][33]

Anaesthetic gases

The most common approach to general anaesthesia is through the use of inhaled general anesthetics. Each has its own potency which is correlated to its solubility in oil. This relationship exists because the drugs bind directly to cavities in proteins of the central nervous system, although several theories of general anaesthetic action have been described. Inhalational anesthetics are thought to exact their effects on different parts of the central nervous system. For instance, the immobilizing effect of inhaled anesthetics results from an effect on the spinal cord whereas sedation, hypnosis and amnesia involve sites in the brain.[44]:515

An inhalational anaesthetic is a chemical compound possessing general anaesthetic properties that can be delivered via inhalation. They are administered by anaesthetists (a term which includes anaesthesiologists, nurse anaesthetists, and anaesthesiologist assistants) through an anaesthesia mask, laryngeal mask airway or tracheal tube connected to an anaesthetic vaporiser and an anaesthetic delivery system. Agents of significant contemporary clinical interest include volatile anaesthetic agents such as isoflurane, sevoflurane and desflurane, and anaesthetic gases such as nitrous oxide and xenon.

Administration

The anaesthetic machine (UK English) or anesthesia machine (US English) or Boyle's machine is used by anaesthesiologists, nurse anaesthetists, and anaesthesiologist assistants to support the administration of anaesthesia. The most common type of anaesthetic machine in use in the developed world is the continuous-flow anaesthetic machine, which is designed to provide an accurate and continuous supply of medical gases (such as oxygen and nitrous oxide), mixed with an accurate concentration of anaesthetic vapour (such as isoflurane), and deliver this to the patient at a safe pressure and flow. Modern machines incorporate a ventilator, suction unit, and patient monitoring devices.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 Brubakk, A. O.; T. S. Neuman (2003). Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th Rev ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd. p. 800. ISBN 0-7020-2571-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 US Navy Diving Manual, 6th revision. United States: US Naval Sea Systems Command. 2006. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Tech Diver. "Exotic Gases". Archived from the original on 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Harlow, V (2002). Oxygen Hacker's Companion. Airspeed Press. ISBN 0-9678873-2-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Millar IL, Mouldey PG (2008). "Compressed breathing air – the potential for evil from within.". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. 38: 145–51. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Acott, Chris (1999). "Oxygen toxicity: A brief history of oxygen in diving". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (3). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Butler FK (2004). "Closed-circuit oxygen diving in the U.S. Navy". Undersea Hyperb Med. 31 (1): 3–20. PMID 15233156. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- 1 2 3 Richardson, Drew; Menduno, Michael; Shreeves, Karl, eds. (1996). "Proceedings of Rebreather Forum 2.0.". Diving Science and Technology Workshop.: 286. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lang, M.A. (2001). DAN Nitrox Workshop Proceedings. Durham, NC: Divers Alert Network. p. 197. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hamilton Jr Robert W; Schreiner Hans R, eds. (1975). Development of Decompression Procedures for Depths in Excess of 400 feet. 9th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. Bethesda, MD: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society. p. 272. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Bowen, Curt. "Heliair: Poor man's mix" (pdf). DeepTech. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- 1 2 3 Fife, William P (1979). "The use of Non-Explosive mixtures of hydrogen and oxygen for diving". Texas A&M University Sea Grant. TAMU-SG-79-201.

- ↑ Rostain, J. C.; M. C. Gardette-Chauffour; C. Lemaire; R. Naquet (1988). "Effects of a H2-He-O2 mixture on the HPNS up to 450 msw.". Undersea Biomed. Res. 15 (4): 257–70. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 3212843. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Brauer RW (ed). (1985). "Hydrogen as a Diving Gas.". 33rd Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Workshop. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society (UHMS Publication Number 69(WS-HYD)3-1-87): 336 pages. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- 1 2 Hamilton Jr, Robert W; Powell, Michael R; Kenyon, David J; Freitag, M (1974). "Neon Decompression". Tarrytown Labs LTD NY. CRL-T-797. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Staff (2007). Marking and Colour Coding of Gas Cylinders, Quads and Banks for Diving Applications IMCA D043 (PDF). London, UK: International Marine Contractors Association. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ↑ Universal Industrial Gases, Inc. (2003). "Non-Cryogenic Air Separation Processes". Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Fowler, B; Ackles, KN; Porlier, G (1985). "Effects of inert gas narcosis on behavior--a critical review". Undersea Biomed. Res. 12 (4): 369–402. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 4082343. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Logan, JA (1961). "An evaluation of the equivalent air depth theory". United States Navy Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-RR-01-61. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Berghage TE, McCraken TM (December 1979). "Equivalent air depth: fact or fiction". Undersea Biomed Res. 6 (4): 379–84. PMID 538866. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Hunger Jr, W. L.; P. B. Bennett (1974). "The causes, mechanisms and prevention of the high pressure nervous syndrome". Undersea Biomed. Res. 1 (1): 1–28. ISSN 0093-5387. OCLC 2068005. PMID 4619860. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ "Thermal Conductivity of common Materials and Gases". Engineering Toolbox. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- 1 2 Ackerman MJ, Maitland G (December 1975). "Calculation of the relative speed of sound in a gas mixture". Undersea Biomed Res. 2 (4): 305–10. PMID 1226588. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Rahn H, Rokitka MA (March 1976). "Narcotic potency of N2, A, and N2O evaluated by the physical performance of mouse colonies at simulated depths". Undersea Biomed Res. 3 (1): 25–34. PMID 1273982. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ D'Aoust BG, Stayton L, Smith LS (September 1980). "Separation of basic parameters of decompression using fingerling salmon". Undersea Biomed Res. 7 (3): 199–209. PMID 7423658. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Pilmanis AA, Balldin UI, Webb JT, Krause KM (December 2003). "Staged decompression to 3.5 psi using argon-oxygen and 100% oxygen breathing mixtures". Aviat Space Environ Med. 74 (12): 1243–50. PMID 14692466. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ "Argon (Ar)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ Lambertsen, C. J. (1971). "Carbon Dioxide Tolerance and Toxicity". Environmental Biomedical Stress Data Center, Institute for Environmental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center. Philadelphia, PA. IFEM Report No. 2-71. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Glatte Jr H. A.; Motsay G. J.; Welch B. E. (1967). "Carbon Dioxide Tolerance Studies". Brooks AFB, TX School of Aerospace Medicine Technical Report. SAM-TR-67-77. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Rosales, KR; Shoffstall, MS; Stoltzfus, JM (2007). "Guide for Oxygen Compatibility Assessments on Oxygen Components and Systems". NASA, Johnson Space Center Technical Report. NASA/TM-2007-213740. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Kizer KW, Golden JA (November 1987). "Lipoid pneumonitis in a commercial abalone diver". Undersea Biomedical Research. 14 (6): 545–52. PMID 3686744. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 217–218, 302. ISBN 9780857111562.

- 1 2 WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 20. ISBN 9789241547659. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 Jamison, Dean T.; Breman, Joel G.; Measham, Anthony R.; Alleyne, George; Claeson, Mariam; Evans, David B.; Jha, Prabhat; Mills, Anne; Musgrove, Philip (2006). Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. World Bank Publications. p. 689. ISBN 9780821361801.

- ↑ Macintosh, Michael; Moore, Tracey (1999). Caring for the Seriously Ill Patient 2E (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780340705827.

- ↑ Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 217–219. ISBN 9780781728454.

- 1 2 Martin, Lawrence (1997). Scuba Diving Explained: Questions and Answers on Physiology and Medical Aspects of Scuba Diving. Lawrence Martin. p. H-1. ISBN 9780941332569.

- ↑ Peate, Ian; Wild, Karen; Nair, Muralitharan (2014). Nursing Practice: Knowledge and Care. John Wiley & Sons. p. 572. ISBN 9781118481363.

- ↑ Agasti, T. K. (2010). Textbook of Anesthesia for Postgraduates. JP Medical Ltd. p. 398. ISBN 9789380704944.

- ↑ Rushman, Geoffrey B.; Davies, N. J. H.; Atkinson, Richard Stuart (1996). A Short History of Anaesthesia: The First 150 Years. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 39. ISBN 9780750630665.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Wyatt, Jonathan P.; Illingworth, Robin N.; Graham, Colin A.; Hogg, Kerstin; Robertson, Colin; Clancy, Michael (2012). Oxford Handbook of Emergency Medicine. OUP Oxford. p. 95. ISBN 9780191016059.

- ↑ Miller, Ronald D (2010). Erikson, Lars I; Fleisher, Lee A; Wiener-Kronish, Jeanine P; Young, William L, eds. Miller's Anesthesia Seventh edition. USA: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06959-8.

External links

- altitude.org. "Altitude oxygen calculator". altitude.org. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- Westfalen (2004). "Fact sheet on Divox" (PDF) (in Dutch). Westfalen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- Taylor, L. "A Brief History Of Mixed Gas Diving". Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- OSHA. "Commercial Diving Regulations (Standards - 29 CFR) - Mixed-gas diving. - 1910.426". U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

%2C_is_fitted_with_a_Kirby_Morgan_37_Dive_Helmet.jpg)