Moorish Revival architecture

Moorish Revival or Neo-Moorish is one of the exotic revival architectural styles that were adopted by architects of Europe and the Americas in the wake of the Romanticist fascination with all things oriental. It reached the height of its popularity after the mid-19th century, part of a widening vocabulary of articulated decorative ornament drawn from historical sources beyond familiar classical and Gothic modes.

In Europe

The "Moorish" garden structures built at Sheringham Hall, Norfolk, ca. 1812, were an unusual touch at the time, a parallel to chinoiserie, as a dream vision of fanciful whimsy, not meant to be taken seriously; however, as early as 1826, Edward Blore used Islamic arches, domes of various size and shapes and other details of Near Eastern Islamic architecture to great effect in his design for Alupka Palace in Crimea, a cultural setting that had already been penetrated by authentic Ottoman styles. By the mid-19th century, the style was adopted by the Jews of Central Europe, who associated Moorish and Mudéjar architectural forms with the golden age of Jewry in medieval Muslim Spain. As a consequence, Moorish Revival spread around the globe as a preferred style of synagogue architecture.

In Spain, the country conceived as the place of origin of Moorish ornamentation, the interest in this sort of architecture fluctuated from province to province. The mainstream was called Neo-Mudéjar. In Catalonia, Antoni Gaudí's profound interest in Mudéjar heritage governed the design of his early works, such as Casa Vicens or Astorga Palace. In Andalusia, the Neo-Mudéjar style gained belated popularity in connection with the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 and was epitomized by Plaza de España (Seville) and Gran Teatro Falla in Cádiz. In Madrid, the Neo-Mudéjar was a characteristic style of housing and public buildings at the turn of the century, while the 1920s return of interest to the style resulted in such buildings as Las Ventas bullring and Diario ABC office. A Spanish nobleman built the Palazzo Sammezzano, one of Europe's largest and most elaborate Moorish Revival structures, in Tuscany between 1853 and 1889.

Although Carlo Bugatti employed Moorish arcading among the exotic features of his furniture, shown at the 1902 exhibition at Turin, by that time the Moorish Revival was very much on the wane almost everywhere. A notable exceptions were Imperial Russia, where the shell-encrusted Morozov House in Moscow (a stylisation of the Pena National Palace in Sintra), the Neo-Mameluk Dulber palace in Koreiz, and the palace in Likani exemplified the continuing development of the style.

Another exception was Bosnia, where, after its occupation by Austria-Hungary, the new authorities commissioned a range of Neo-Moorish structures. The aim was to promote Bosnian national identity while avoiding its association with either the Ottoman Empire or the growing pan-Slavic movement by creating an "Islamic architecture of European fantasy".[2] This included application of ornamentations and other Moorish design strategies neither of which had much to do with prior architectural direction of indigenous Bosnian architecture. The central post office in Sarajevo, for example, follows distinct formal characteristics of design like clarity of form, symmetry, and proportion while the interior followed the same doctrine. The National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo is an example of Pseudo Moorish architectural language using decorations and pointed arches while still integrating other formal elements into the design.

In the United States

In the United States, Washington Irving's fanciful travel sketch, Tales of the Alhambra (1832), first brought Moorish Andalusia into readers' imaginations; one of the first neo-Moorish structures was Iranistan, a mansion of P. T. Barnum in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Constructed in 1848 and destroyed by fire ten years later, this architectural extravaganza "sprouted bulbous domes and horseshoe arches".[3] In the 1860s, the style spread across America, with Olana, the painter Frederic Edwin Church's house overlooking the Hudson River, Castle Garden in Jacksonville and Longwood in Natchez, Mississippi usually cited among the more prominent examples. After the American Civil War, Moorish or Turkish smoking rooms achieved some popularity. There were Moorish details in the interiors created for the Henry Osborne Havemeyer residence on Fifth Avenue by Louis Comfort Tiffany. The 1914 Pittock Mansion in Portland, Oregon incorporates Turkish design features, as well as French, English, and Italian ones; the smoking room in particular has notable Moorish revival elements. In 1937, the Corn Palace in Mitchell, South Dakota added unusual minarets and Moorish domes, unusual because the polychrome decorations are made out of corn cobs of various colors assembled like mosaic tiles to create patterns. The 1891 Tampa Bay Hotel, whose minarets and Moorish domes are now the pride of the University of Tampa, was a particularly extravagant example of the style. Other schools with Moorish Revival buildings include Yeshiva University in New York City. George Washington Smith used the style in his design for the 1920s Isham Beach Estate in Santa Barbara, California.[4]

Theaters

In the United States

| Theater | City and State | Architect | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alhambra Theatre | El Paso, Texas | Henry C. Trost | 1914 |

| Alhambra Theatre | Evansville, Indiana | Frank J. Schlotter | 1913 |

| Alhambra Theatre | Birmingham, Alabama | Graven & Maygar | 1927 |

| Alhambra Theatre | Hopkinsville, Kentucky | John Walker | 1928 |

| Alhambra Theatre | San Francisco, California | Miller and Pflueger | 1925 |

| Altria Theater | Richmond, Virginia | Marcellus E. Wright Sr., Charles M. Robinson | 1927 |

| Bagdad Theatre | Portland, Oregon | Thomas & Mercier | 1927 |

| The Carpenter Center | Richmond, Virginia | John Eberson | 1928 |

| Civic Theatre | Akron, Ohio | John Eberson | 1929 |

| Emporia Granada Theatre | Emporia, Kansas | Boller Brothers | 1929 |

| Fox Theatre | Atlanta, Georgia | Mayre, Alger & Vinour | 1929 |

| Fox Theatre | North Platte, Nebraska | Elmer F. Behrens | 1929 |

| Granada Theater | The Dalles, Oregon | William Cutts | 1929 |

| Keith's Flushing Theater | Queens, New York | Thomas Lamb | 1928 |

| Olympic Theatre | Miami, Florida | John Eberson | 1926 |

| Liberty Theatre | North Bend, Oregon | Tourtellotte & Hummel | 1924 |

| Lincoln Theater | Los Angeles, California | John Paxton Perrine | 1927 |

| Loew's 72nd Street Theatre | New York City | Thomas W. Lamb | 1932 (dem.) |

| The Majestic Theatre | San Antonio, Texas | John Eberson | 1929 |

| Mount Baker Theatre | Bellingham, Washington | Robert Reamer | 1927 |

| Music Box Theatre | Chicago, Illinois | Louis J. Simon | 1929 |

| Palace Theatre | Canton, Ohio | John Eberson | 1926 |

| Plaza Theatre | El Paso, Texas | W. Scott Donne | 1930 |

| Saenger Theater | Hattiesburg, Mississippi | Emile Weil | 1929 |

| Shrine Auditorium | Los Angeles, California | Lansburgh, Austin and Edelman | 1926 |

| Sooner Theatre | Norman, Oklahoma | Harold Gimeno | 1929 |

| Temple Theatre | Meridian, Mississippi | Emile Weil | 1927 |

| Tennessee Theatre | Knoxville, Tennessee | Graven & Mayger | 1928 |

| Tower Theatre | Los Angeles, California | S. Charles Lee | 1927 |

Around the world

| Theater | Photo | City and State | Country | Architect | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tbilisi Opera and Ballet Theatre | |

Tbilisi | Georgia | Giovanni Scudieri | 1851, rebuilt 1896 |

| Eastern Arcade (former Palace/Metro Theatre) |  |

Melbourne, Victoria | Australia | Hyndman & Bates | 1894 (demolished in 2008) |

| Odessa Philharmonic Theater | |

Odessa | Ukraine | Alexander Bernardazzi | 1898 |

| State/Forum Theatre |  |

Melbourne, Victoria | Australia | Bohringer, Taylor & Johnson | 1929 |

Synagogues

Europe

- Munich synagogue, by Friedrich von Gärtner, 1832 was the earliest Moorish revival synagogue (destroyed on Kristallnacht)

- Semper Synagogue, by Gottfried Semper, Dresden, 1839–40 (destroyed on Kristallnacht)

- Leopoldstädter Tempel, Vienna, Austria, 1853-58 (destroyed on Kristallnacht)

- Dohány Street Synagogue, Budapest, Hungary, 1854–1859

- Leipzig synagogue, 1855 (destroyed on Kristallnacht in 1938)

- Glockengasse synagogue, Cologne, Germany, 1855-61 (destroyed on Kristallnacht)

- New Synagogue by Eduard Knoblauch, Berlin, 1859–1866

- New Synagogue, Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland, 1857–1860

- Tempel Synagogue, Cracow, Poland, 1860–62

- Cetate Synagogue, Timişoara, Romania, by Ignaz Schumann, 1864–65

- Zagreb Synagogue, 1867

- The Great Synagogue of Stockholm, Sweden, by Fredrik Wilhelm Scholander, 1867–1870

- Spanish Synagogue, Prague, 1868

- Rumbach Street synagogue, Budapest, Hungary, 1872

- Czernowitz Synagogue, Czernowitz, Ukraine, 1873

- Great Synagogue of Florence, Tempio Maggiore, Florence, Italy, 1874–82

- Princes Road Synagogue, Liverpool, England, 1874

- Manchester Jewish Museum, built as a Sephardic synagogue, Manchester, England, 1874

- Vercelli Synagogue, Vercelli, Italy, 1878

- Vrbové synagogue, Vrbové, Slovakia, 1883

- Turin synagogue, Italy, 1884

- Great Synagogue in Pilsen, Pilsen, Bohemia, Czech Republic, 1888

- The Grand Choral Synagogue, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1888

- Fabric New Synagogue in Timişoara,Romania, by Lipot Baumhorn, 1889

- Rosenberg synagogue, Olesno, Poland, 1889 (destroyed on Kristallnacht in 1938)

- La Ferté-sous-Jouarre synagogue, France, 1891

- Prešov synagogue, Prešov, Slovakia, 1898

- The Great Choral Synagogue, Kiev, Ukraine, 1895

- Opava synagogue, Czech Republic, 1895

- Olomouc Synagogue, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 1897 (destroyed in 1938)

- Košice synagogue, Košice, Slovakia, 1899, interior of Rundbogenstil building

- Malacky synagogue, Slovakia, 1886, rebuilt 1900

- Sarajevo Synagogue, 1902

- Karaite Kenesa, Kiev, 1902

- Jubilee Synagogue, Prague, Czech Republic, 1906

- Groningen Synagogue, Groningen, Netherlands, 1906

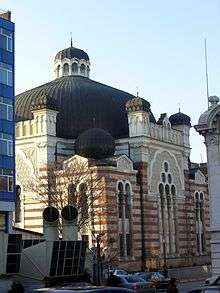

- Sofia Synagogue, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1909

- Galitska Synagogue, Kiev, Ukraine, 1909

- Uzhgorod Synagogue, Uzhgorod, Ukraine, 1910

United States

- Isaac M. Wise Temple, also known as the Plum Street Temple, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1865

- Congregation Rodeph Shalom, Philadelphia, 1866 (no longer standing)

- Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue at 43rd Street, Congregation Emanu-El of the City of New York built in 1868, designed by Leopold Eidlitz, assisted by Henry Fernbach, (no longer standing)

- Temple B’nai Sholom, Quincy, Illinois, 1870

- Central Synagogue, Upper East Side, Manhattan, New York, 1872

- Vine Street Temple, Nashville, Tennessee, 1874

- Charter Oak Temple (Congregation Beth Israel), Hartford, Connecticut, 1876

- B'nai Israel Synagogue (Baltimore), Maryland, 1876

- Temple Adath Israel, Owensboro, Kentucky, 1877

- Prince Street Synagogue (Oheb Shalom,) Newark, New Jersey, 1884

- Eldridge Street Synagogue, Lower East Side, Manhattan, New York, 1887

- Congregation Beth Israel of Portland, Oregon, 1888 (no longer standing)

- Park East Synagogue, Upper East Side, Manhattan, New York, 1889

- Gemiluth Chessed, Port Gibson, Mississippi, 1891

- Temple Emanu-El (Helena, Montana), 1891[5]

- Temple Beth-El, Corsicana, Corsicana, Navarro County, Texas, 1898–1900

- Temple Sinai (Sumter, South Carolina), 1912

- Ohabei Shalom, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1925

- Congregation Ohab Zedek, Upper West Side, Manhattan, New York, 1926

- Congregation Rodeph Shalom, Philadelphia, 1928

Latin America

- Sephardic Temple, Barracas district, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Churches and cathedrals

- The Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, Gibraltar (1825–1832) an early example of Moorish revival architecture is located in Gibraltar, which formed part of Moorish Al-Andalus between 711 and 1462 AD.

- Immaculate Conception Church (New Orleans), (a.k.a. Jesuit Church) is a striking example of Moorish Revival Architecture. Across the street was the College of the Immaculate Conception, housing a chapel with two stained glass domes. The chapel was disassembled and about half of it (one of the stained glass domes, eleven of the windows) was installed in the present Jesuit High School.

Shriners Temples

The Shriners, a fraternal organization, often chose a Moorish Revival style for their Temples. Architecturally notable Shriners Temples include:

- Acca Temple Shrine, Richmond, Virginia, currently Altria Theater, formerly 'The Landmark Theater' and 'The Mosque'

- Algeria Shrine Temple, Helena, Montana

- Almas Temple, Washington D.C.

- El Zaribah Shrine Auditorium, Phoenix, Arizona

- Medinah Temple, Chicago, Illinois now a Bloomingdale's.

- Murat Shrine, Indianapolis, Indiana, the largest Shrine temple in North America, now officially known as Old National Centre.

- New York City Center, now used as a concert hall

- Shrine Auditorium, Los Angeles, California

- Tripoli Shrine Temple, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Zembo Mosque, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- The Scottish Rite Temple in Santa Fe, New Mexico, while not a Shrine Temple, is a Masonic building that uses the Moorish Revival architectural style.

Other buildings

- The Zacherlfabrik, Vienna, 1892

- City hall, Brcko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1892

- City hall, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1894

- Jewish Hospital, Lviv, Ukraine, 1900

- Mostar Gymnasium, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1902

- Former Yenidze Cigarette Factory, Dresden, Germany, 1908 (here, the "minarets" are used to disguise smokestacks)

- Casamaures, Saint-Martin-le-Vinoux, France, 1855

- Villa Zorayda, St. Augustine, FL, 1883

- Campo Pequeno bullring, Lisbon, 1892

- Henry B. Plant Museum, Tampa, FL, 1891

Gallery

Immaculate Conception Church (New Orleans), 1851, rebuilt 1930

Immaculate Conception Church (New Orleans), 1851, rebuilt 1930 Leopoldstädter Tempel, Vienna, Austria, 1858

Leopoldstädter Tempel, Vienna, Austria, 1858 Spanish Synagogue (Prague), Czech Republic, 1868

Spanish Synagogue (Prague), Czech Republic, 1868- Florence synagogue, Italy, 1882

- Turin synagogue, Italy, 1884

Fabric New Synagogue in Timişoara, Romania, 1889

Fabric New Synagogue in Timişoara, Romania, 1889 Tampa Bay Hotel, Tampa, Florida, 1891

Tampa Bay Hotel, Tampa, Florida, 1891 The Grand Choral Synagogue, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1893

The Grand Choral Synagogue, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1893- Great Synagogue, Plzeň, Czech Republic, 1893

- National Library, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1894

- Likani Palace, Georgia, 1895

Arseny Morozov House, Moscow, Russia, 1899

Arseny Morozov House, Moscow, Russia, 1899 Former Jewish Hospital in Lviv, Ukraine, 1901

Former Jewish Hospital in Lviv, Ukraine, 1901 Mostar Gymnasium, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1902

Mostar Gymnasium, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1902

Uzhgorod Synagogue, 1910

Uzhgorod Synagogue, 1910

.jpg) Kórnik Castle, Poland

Kórnik Castle, Poland

See also

Notes

- ↑ Brett, C.E.B. (2005). Towers of Crim Tartary : English and Scottish architects and craftsmen in the Crimea, 1762–1853. Donington, Lincolnshire: Shaun Tyas. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-900289-73-3.

- ↑ Joseph, Suad; Najmabadi, Afsaneh (2003). Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures: Economics, education, mobility, and space. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9004128204.

- ↑ John C. Poppeliers, S. Allen Chambers Jr. What Style Is It: A Guide to American Architecture, p. 63. ISBN 0-471-25036-8 .

- ↑ Gebhard, David. Santa Barbara Architecture, from Spanish Colonial to Modern. Capra Press. Santa Barbara. 1980. (later editions avail.) p. 109

- ↑

Sources

- Naylor, David, Great American Movie Theaters, The Preservation Press, Washington, D.C., 1987

- Thorne, Ross, Picture Palace Architecture in Australia, Sun Books Pty. Ltd., South Melbourne, Australia, 1976

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moorish Revival architecture. |