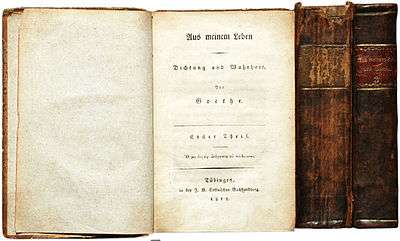

Dichtung und Wahrheit

Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit (From my Life: Poetry and Truth; 1811–1833) is an autobiography by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe that comprises the time from the poet's childhood to the days in 1775, when he was about to leave for Weimar.

Structure

The book is divided into four parts, the first three of which were written and published between 1811–14, while the fourth was written mainly in 1830-31 and published in 1833. Each part contains five books. The whole covers the first 26 years of its author's life. Goethe held that “the most important period of an individual is that of his development.”[1]

History

Goethe dictated schemes and drafts for Dichtung und Wahrheit, after he had finished his Theory of Colours, in summer 1810 in Carlsbad.[2] He first worked on the autobiography in parallel to his work on Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years; from January 1811 on, the autobiography became his main endeavor.[2] Goethe asked Bettina von Arnim to send him the notes that she had written down about his youth on the basis of meetings she had had with his mother out of a related interest. When Bettina had complied with this wish, the poet mainly used her notes for a depiction of his mother, Aristeia der Mutter, which he did not include in the autobiography.[2] He also asked Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich von Trebra, Karl Ludwig von Knebel, and Johann Friedrich Heinrich Schlosser for help.[3]

Goethe's intentions

Goethe wrote Dichtung und Wahrheit from the point of view of the scientist, the historian and the artist. As a scientist, he wished to picture his life as developing stage by stage “according to those laws which we observe in the metamorphosis of the plants.” As a historian, he portrayed the general conditions of the times and revealed the relations between them and the individual. As an artist, he did not feel bound to facts for their own sake, but selected those that were of significance and moulded them so that they might become parts of a work of art.[1]

As far as art is concerned, the word Dichtung (meaning both poetry and fiction) is deliberately ambiguous, indicating that the author has systematically selected those events which he considered it desirable to mention. Goethe also created a partially fictitional image of some figures and events, including Friederike Brion for example, which are more vivid than any attempt at faithful description could have been.[4] Germanists have even doubted that the figure of Gretchen, who first appears as a barmaid, really existed at all, although she reappears as Margarete, also called Gretchen, the central female character in Goethe's drama Faust.[5]

Contents

The material in the first three parts is distributed in such a way that Goethe's childhood is narrated from book one to the middle of book six, the account of his student days begins with the latter half of the sixth book and continues through the 11th book, books 12-15 are given to the consideration of his early manhood, when his first great successes as an author were realized. In spite of important experiences, part four does not open a new phase in Goethe's development, but it does bring the outer course of his life to its most decisive turning point — his departure from Weimar.[1]

Goethe depicts his happy childhood in Frankfurt, his relationship with his sister Cornelia, and his infatuation with Gretchen. Gretchen is described as "unbelievably beautiful", but Goethe also mentions that she had appeared superficial to him, when he heard she had referred to him as to a child, in the course of criminal investigations. Goethe moreover depicts his love-affairs with Anna Katharina Schönkopf during his time as a student in Leipzig, with Friederike Brion during his time in Strasburg, and with the Frankfurt banker's daughter Lili Schönemann. Dichtung und Wahrheit also mirrors Goethe's development as a poet and partly expounds the changes in the author's thinking that were brought about by the Seven Years' War and the French occupation, while other experiences throughout are presented and colored.

Not least, this autobiography contains the coinage of the Latin expression nemo contra Deum nisi Deus ipse[6] (no one against God except God himself), that had so much resonance in theology[7] and philosophy,[8] atheistic but not only.

References

- 1 2 3

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ewald Eiserhardt (1920). "Poetry and Truth". In Rines, George Edwin. Encyclopedia Americana.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ewald Eiserhardt (1920). "Poetry and Truth". In Rines, George Edwin. Encyclopedia Americana. - 1 2 3 Karl Robert Mandelkow, Bodo Morawe: Goethes Briefe. 1. edition. Vol. 3: Briefe der Jahre 1805-1821. Christian Wegner publishers, Hamburg 1965, p. 569

- ↑ Karl Robert Mandelkow, Bodo Morawe: Goethes Briefe. 1. edition. Vol. 3: Briefe der Jahre 1805-1821. Christian Wegner publishers, Hamburg 1965, p. 569-570

- ↑ Herman Grimm: Goethe. Vorlesungen gehalten an der Königlichen Universität zu Berlin. Vol. 1. J.G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, Stuttgart / Berlin 1923, p. 67-68

- ↑ Karl Goedeke: Goethes Leben. Cotta / Kröner, Stuttgart around 1883, p. 16

- ↑ Page 598 (part four, book twenty).

- ↑ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ↑ See occurrences on Google Books.

External links

- Autobiography: Truth and Fiction Relating to My Life at Project Gutenberg (English translation by John Oxenford), books 1–9

- The Autobiography of Johann Goethe: Truth and Poetry from my own Life archive.org, books 1–13

- The Autobiography of Johann Goethe: Truth and Poetry from my own Life archive.org, books 10–20

- Memoirs of Goethe: written by himself Printed for Henry Colburn 1824

- The Autobiography of Johann Goethe: Truth and Poetry from my own Life Librivox free audio, books 1–9

- The Autobiography of Johann Goethe: Truth and Poetry from my own Life Librivox free audio, books 10–13

- First printing (German)