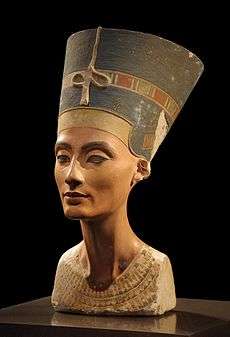

Nefertiti Bust

|

The iconic bust of Nefertiti is part of the Egyptian Museum of Berlin collection, currently on display in the Neues Museum. | |

| Material | limestone and stucco[1] |

|---|---|

| Size | Height: 48 centimetres (19 in) |

| Created | 1345 BC: by Thutmose, ancient Egypt |

| Discovered | 1912: Amarna, Egypt |

| Present location | Neues Museum, Berlin, Germany |

The Nefertiti Bust is a painted stucco-coated limestone bust of Nefertiti, the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten.[2] The work is believed to have been crafted in 1345 B.C. by the sculptor Thutmose, because it was found in his workshop in Amarna, Egypt.[3] It is one of the most copied works of ancient Egypt. Owing to the work, Nefertiti has become one of the most famous women of the ancient world, and an icon of feminine beauty.

A German archaeological team led by Ludwig Borchardt discovered the bust in 1912 in Thutmose's workshop.[4] It has been kept at various locations in Germany since its discovery, including the cellar of a bank, a salt mine in Merkers-Kieselbach, the Dahlem museum, the Egyptian Museum in Charlottenburg and the Altes Museum.[5] It is currently on display at the Neues Museum in Berlin, where it was originally displayed before World War II.[6]

The Nefertiti bust has become a cultural symbol of Berlin as well as ancient Egypt. Nefertiti herself has become quite an icon. Nefertiti is widely known for her beauty and versatility. It has also been the subject of an intense argument between Egypt and Germany over Egyptian demands for its repatriation. It was dragged into controversy by the Body of Nefertiti art exhibition and also by doubts over its authenticity.[7] However various testing and analysis of the bust have proved it to be authentic.

History

Background

Nefertiti (meaning "the beautiful one has come forth") was the 14th-century BC Great Royal Wife (chief consort) of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt. Akhenaten initiated a new monotheistic form of worship called Atenism dedicated to the Sun disc Aten.[8] Little is known about Nefertiti. Theories suggest she could have been an Egyptian royal by birth, a foreign princess or the daughter of a high government official named Ay, who became pharaoh after Tutankhamun. She may have been the co-regent of Egypt with Akhenaten, who ruled from 1352 BC to 1336 BC.[8] Nefertiti bore six daughters to Akhenaten, one of whom, Ankhesenpaaten (renamed Ankhesenamun after the suppression of the Aten cult), married Tutankhamun, Nefertiti's stepson. Nefertiti was thought to have disappeared from history in the twelfth year of Akhenaten's reign, though whether this is due to her death or because she took a new name is not known. She may also have later become a pharaoh in her own right, ruling alone for a short time after her husband's death.[8][9] However, it is now known that she was still alive in the sixteenth year of her husband's reign from a limestone quarry inscription found at Dayr Abū Ḥinnis.[10] Dayr Abū Ḥinnis is located "on the eastern side of the Nile, about ten kilometres north of Amarna."[11]

The bust of Nefertiti is believed to have been crafted about 1345 BC by the sculptor Thutmose.[8][12] The bust does not have any inscriptions, but can be certainly identified as Nefertiti by the characteristic crown, which she wears in other surviving (and clearly labelled) depictions, for example the 'house altar'.[13]

Discovery

The Nefertiti bust was found on 6 December 1912 at Amarna by the German Oriental Company (Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft – DOG), led by German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt. It was found in what had been the sculptor Thutmose's workshop, along with other unfinished busts of Nefertiti.[14][15] Borchardt's diary provides the main written account of the find; he remarks, "Suddenly we had in our hands the most alive Egyptian artwork. You cannot describe it with words. You must see it."[16]

A 1924 document found in the archives of the German Oriental Company recalls the 20 January 1913 meeting between Ludwig Borchardt and a senior Egyptian official to discuss the division of the archeological finds of 1912 between Germany and Egypt. According to the secretary of the German Oriental Company (who was the author of the document and who was present at the meeting), Borchardt "wanted to save the bust for us".[1][17] Borchardt is suspected of having concealed the bust's real value,[18] although he denied doing so.[19]

While Philipp Vandenberg describes the coup as "adventurous and beyond comparison",[20] Time magazine lists it among the "Top 10 Plundered Artifacts".[21] Borchardt showed the Egyptian official a photograph of the bust "that didn't show Nefertiti in her best light". The bust was wrapped up in a box when Egypt's chief antiques inspector Gustave Lefebvre came for inspection. The document reveals that Borchardt claimed the bust was made of gypsum to mislead the inspector. The German Oriental Company blames the negligence of the inspector and points out that the bust was at the top of the exchange list and says the deal was done fairly.[17][22]

Description and examinations

The bust of Nefertiti is 48 centimetres (19 in) tall and weighs about 20 kilograms (44 lb). It is made of a limestone core covered with painted stucco layers. The face is completely symmetrical and almost intact, but the left eye lacks the inlay present in the right.[23][24] The pupil of the right eye is of inserted quartz with black paint and is fixed with beeswax. The background of the eye-socket is unadorned limestone. Nefertiti wears her characteristic blue crown known as the "Nefertiti cap crown" with a golden diadem band looped around like horizontal ribbons and joining at the back, and an Uraeus (cobra) over her brow – which is now broken. She also wears a broad collar with a floral pattern on it.[25] The ears also have suffered some damage.[24] Gardner's Art Through the Ages suggests that "With this elegant bust, Thutmose may have been alluding to a heavy flower on its slender sleek stalk by exaggerating the weight of the crowned head and the length of the almost serpentine neck."[26]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

According to David Silverman, the Nefertiti bust reflects the classical Egyptian art style, deviating from the "eccentricities" of the Amarna art style, which was developed in Akhenaten's reign. The exact function of the bust is unknown, though it is theorized that the bust may be a sculptor's modello to be used as a basis for other official portraits, kept in the artist's workshop.[27]

Colors

Ludwig Borchardt commissioned a chemical analysis of the colored pigments of the head. The result of the examination was published in the book Portrait of Queen Nofretete in 1923:[28]

- Blue: powdered frit, colored with copper oxide

- Skin color (light red): fine powdered lime spar colored with red chalk (iron oxide)

- Yellow: orpiment (arsenic sulfide)

- Green: powdered frit, colored with copper and iron oxide

- Black: coal with wax as a binding medium

- White: chalk

Missing left eye

When the bust was first discovered, no piece of quartz to represent the iris of the left eyeball was present, as in the other eye, and none was found despite an intensive search and a then significant reward of £5 being put up for information regarding its whereabouts.[29] Borchardt assumed that the quartz iris of the left eye had fallen out when the sculptor Thutmose's workshop fell into ruin.[30] The missing eye led to speculation that Nefertiti may have suffered from an ophthalmic infection, and actually lost her left eye, though the presence of an iris in other statues of her contradicted this possibility.[31]

Dietrich Wildung proposed that the bust in Berlin was a model for official portraits and was used by the master sculptor for teaching his pupils how to carve the internal structure of the eye, and thus the left iris was not added.[32] Gardner's Art Through the Ages and Silverman presents a similar view that the bust was deliberately kept unfinished.[24][26] Hawass suggested that Thutmose had created the left eye, but it was later destroyed.[33]

CT scans

The bust was first CT scanned in 1992, with the scan producing cross sections of the bust every 5 millimetres (0.20 in).[34][35] In 2006, Dietrich Wildung, the director of Berlin's Egyptian Museum, while trying a different lighting at the Altes Museum—where the bust was then displayed—observed wrinkles on Nefertiti's neck and bags under her eyes, suggesting the sculptor had tried to depict signs of aging. A CT scan confirmed Wildung's findings; Thutmose had added gypsum under the cheeks and eyes in an attempt to perfect his sculpture, Wildung explained.[32]

The CT scan in 2006, led by Alexander Huppertz, the director of the Imaging Science Institute in Berlin, revealed a wrinkled face of Nefertiti carved in the inner core of the bust.[35] The results were published in the April 2009 Radiology journal.[36] The scan revealed that Thutmose placed layers of varying thickness on top of the limestone core. The inner face has creases around her mouth and cheeks and a swelling on the nose. The creases and the bump on the nose are leveled by the outermost stucco layer. According to Huppertz, this may reflect "aesthetic ideals of the era".[12][37] The 2006 scan provided greater detail than the 1992 one, revealing subtle details just 1–2 mm under the stucco.[34]

Later history

The bust of Nefertiti has become "one of the most admired, and most copied, images from ancient Egypt", and the star exhibit used to market Berlin's museums.[38] It is seen as an "icon of international beauty".[18][32][39] "Showing a woman with a long neck, elegantly arched brows, high cheekbones, a slender nose and an enigmatic smile played about red lips, the bust has established Nefertiti as one of the most beautiful faces of antiquity."[32] It is described as the most famous bust of ancient art, comparable only to the mask of Tutankhamun.[25]

Nefertiti has become an icon of Berlin's culture.[14] Some 500,000 visitors see Nefertiti every year.[17] The bust is described as "the best-known work of art from ancient Egypt, arguably from all antiquity".[40] Her face is on postcards of Berlin and 1989 German postage stamps.[39][41]

Locations in Germany

The Nefertiti bust has been in Germany since 1913,[1] when it was shipped to Berlin and presented to James Simon, a wholesale merchant and the sponsor of the Amarna excavation.[15] It was displayed at Simon's residence until 1913, when Simon loaned the bust and other artifacts from the Amarna dig to the Berlin Museum.[42] Although the rest of the Amarna collection was displayed in 1913–14, Nefertiti was kept secret at Borchardt's request.[20] In 1918, the Museum discussed the public display of the bust, but again kept it secret on the request of Borchardt.[42] It was permanently donated to the Berlin Museum in 1920. Finally, in 1923, the bust was first unveiled to the public in Borchardt's writing and later in 1924, displayed to the public as part of the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.[20][42] The bust created a sensation, swiftly becoming a world-renowned icon of feminine beauty, and one of the most universally-recognised artifacts to survive from Ancient Egypt. The Nefertiti bust was displayed in Berlin’s Neues Museum on Museum Island until the museum was closed in 1939; with the onset of World War II, the Berlin museums were emptied and the artifacts moved to secure shelters for safekeeping.[15] Nefertiti was initially stored in the cellar of the Prussian Governmental Bank and then, in the autumn of 1941, moved to the tower of a flak bunker in Berlin.[42] The Neues Museum suffered bombings in 1943 by the Royal Air Force.[43] On 6 March 1945, the bust was moved to a German salt mine at Merkers-Kieselbach in Thuringia.[15]

In March 1945, the bust was found by the American Army and given over to its Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives branch. It was moved to the Reichsbank in Frankfurt and then, in August, shipped to the U.S. Central Collecting Point in Wiesbaden where it was displayed to the public in 1946.[15][42] In 1956, the bust was returned to West Berlin.[15] There it was displayed at the Dahlem Museum. As early as 1946, East Germany (German Democratic Republic) insisted on the return of Nefertiti to Museum Island in East Berlin, where the bust had been displayed before the war.[15][42] In 1967, Nefertiti was moved in the Egyptian Museum in Charlottenburg and remained there until 2005, when it was moved to the Altes Museum.[42] The bust returned to the Neues Museum as its centerpiece when the museum reopened in October 2009.[18][43][44]

Controversies

| |

|

|

Requests for repatriation to Egypt

Ever since the official unveiling of the bust in Berlin in 1924, the Egyptian authorities have been demanding its return to Egypt.[14][42][46] In 1925, Egypt threatened to ban German excavations in Egypt unless Nefertiti was returned. In 1929, Egypt offered to exchange other artifacts for Nefertiti, but Germany declined. In the 1950s, Egypt again tried to initiate negotiations but there was no response from Germany.[42][46] Although Germany had previously strongly opposed the repatriation, in 1933 Hermann Göring considered returning the bust to King Farouk Fouad of Egypt as a political gesture. Hitler opposed the idea, and told the Egyptian government that he would build a new Egyptian museum for Nefertiti: "In the middle, this wonder, Nefertiti, will be enthroned, ... I will never relinquish the head of the Queen."[18][46] While the bust was under American control, Egypt requested the United States to hand it over; the USA refused and advised Egypt to take up the matter with the new German authorities.[42] In 1989, the Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak viewed the bust and announced that Nefertiti was "the best ambassador for Egypt" in Berlin.[42]

Dr. Zahi Hawass, the former Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, believes that Nefertiti belongs to Egypt and that the bust was taken out of Egypt illegally and should therefore be returned. Dr. Hawass has maintained the stance that Egyptian authorities were misled over the acquisition of Nefertiti in 1913. He has demanded that Germany prove that it was exported legally.[1][47] According to Kurt G. Siehr, another argument in support of repatriation is that "Archeological finds have their 'home' in the country of origin and should be preserved in that country."[48] The Nefertiti repatriation issue sprang up again in 2003 over the Body of Nefertiti sculpture (see Controversy). In 2005, Hawass requested UNESCO to intervene to return the bust.[49]

In 2007, Hawass threatened to ban exhibitions of Egyptian artifacts in Germany if Nefertiti was not lent to Egypt, but to no avail. Hawass also requested a worldwide boycott of loans to German museums to initiate what he calls a "scientific war". Hawass wanted Germany to at least lend the bust to Egypt in 2012 for the opening of the new Grand Egyptian Museum near the Great Pyramids of Giza.[38] Simultaneously, a campaign called "Nefertiti Travels" was launched by cultural association CulturCooperation, based in Hamburg, Germany. They distributed postcards depicting the bust of Nefertiti with the words "Return to Sender" and wrote an open letter to the German Culture Minister, Bernd Neumann, supporting the view that Egypt should be given the bust on loan.[39][50] In 2009, when Nefertiti moved back to the Neues Museum – her old home, the appropriateness of Berlin as the bust's location was questioned.

Several German art experts have attempted to refute all the claims made by Hawass, pointing to the 1924 document discussing the pact between Borchardt and the Egyptian authorities,[1][17] though, as discussed earlier, Borchardt has been accused of foul play in the deal. The German authorities have also argued the bust is too fragile to transport and that the legal arguments for the repatriation were insubstantial. According to The Times, Germany may be concerned that lending the bust to Egypt would mean its permanent departure from Germany.[18][38]

In December 2009 Friederike Seyfried, the director of Berlin's Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection, presented to the Egyptians documents held by the museum regarding the discovery of the bust which include a protocol signed by the German excavator of the bust and the Egyptian Antiquities Service. In the documents, the object was listed as a painted plaster bust of a princess. But in the diary of Ludwig Borchardt he clearly referred to it as the head of Nefertiti. "This proves that Borchardt wrote this description so that his country can get the statue," Hawass commented "These materials confirm Egypt's contention that (he) did act unethically with intent to deceive." However, Hawass said Egypt didn't consider the Nefertiti bust to be a looted antiquity. Still, it is one of a handful of truly singular Egyptian antiquities still in foreign hands. "I really want it back," he said.[38] Hawass' statement quoted the director of the museum as saying the authority to approve the return of the bust to Egypt lies with the Prussian Cultural Heritage and the German culture minister.[51]

Allegations over authenticity

The French book, Le Buste de Nefertiti – une Imposture de l'Egyptologie? (The Bust of Nefertiti – a Fraud in Egyptology?) by Swiss art historian Henri Stierlin and the book Missing Link in Archaeology by Berlin author and historian Erdogan Ercivan both claimed that the Nefertiti bust was a modern fake. Stierlin claims that Borchardt may have created the bust to test ancient pigments and that when the bust was admired by Prince Johann Georg of Saxony, Borchardt pretended it was genuine to avoid offending the prince. Stierlin argues that the missing left eye of the bust would have been a sign of disrespect in ancient Egypt, that no scientific records of the bust appear until 11 years after its supposed discovery, and while the paint pigments are ancient, the inner limestone core has never been dated. Ercivan suggests Borchardt's wife was the model for the bust, and both authors argue that it was not revealed to the public until 1924 because it was a fake.[16] Another theory suggested that the existing Nefertiti bust was crafted in the 1930s on Hitler's orders, and that the original was lost in World War II.[22]

_1988%2C_MiNr_814.jpg)

Dietrich Wildung dismissed the claims as a publicity stunt, as radiological tests, detailed computer tomography, and material analysis have proved its authenticity.[16] The pigments used on the bust have been matched to those used by ancient Egyptian artisans. The 2006 CT scan that discovered the "hidden face" of Nefertiti proved without doubt – according to Science News – that the bust was genuine.[22]

Egyptian authorities also dismissed Stierlin's theory. Dr Zahi Hawass said "Stierlin is not a historian. He is delirious." Although Stierlin had argued "Egyptians cut shoulders horizontally" and Nefertiti had vertical shoulders, Hawass said that the new style seen in the Nefertiti bust is part of the changes introduced by Akhenaten, the husband of Nefertiti. Hawass also claimed that the sculptor Thutmose had created the eye, but it was later destroyed.[33]

The Body of Nefertiti

In 2003, the Egyptian Museum in Berlin allowed the Hungarian artist duo Little Warsaw, Andras Galik and Balint Havas, to place the bust atop a nearly nude female bronze for a video installation to be shown at the Venice Biennale modern art festival. The project called the Body of Nefertiti was, according to the artists, an attempt to pay homage to the bust. According to Wildung, it showed "the continued relevance of the ancient world to today's art."[52] However, Egyptian cultural officials took offense and proclaimed it to be a disgrace to "one of the great symbols of their country's history". As a consequence, they also banned Wildung and his wife from further exploration in Egypt.[38][52][53] The Egyptian Minister for Culture, Farouk Hosny, declared that Nefertiti was "not in safe hands", and although Egypt had not renewed their claims for restitution "due to the good relations with Germany," this "recent behaviour" was unacceptable.[42]

Cultural significance

In 1930, the German press described the Nefertiti bust as their new monarch, personifying it as a queen. As the "'most precious ... stone in the setting of the diadem' from the art treasures of 'Prussia Germany'", Nefertiti would re-establish the imperial German national identity after 1918.[54] Hitler described the bust as "a unique masterpiece, an ornament, a true treasure", and pledged to build a museum to house it.[16] By the 1970s, the bust had become an issue of national identity to both German states—East Germany and West Germany—created after World War II.[54] In 1999, Nefertiti appeared on an election poster for the green political party Bündnis 90/Die Grünen as a promise for cosmopolitan and multi-cultural environment with the slogan "Strong Women for Berlin!"[41] According to Claudia Breger, another reason that the Nefertiti bust became associated with a German national identity was its place as a rival to the Tutankhamun find by the British, who then ruled Egypt.[41]

The bust became an influence on popular culture with Jack Pierce's make-up work on Elsa Lanchester's iconic hair style in the film Bride of Frankenstein being inspired by it.[55]

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dempsy, Judy (18 October 2009). "A 3,500-Year-Old Queen Causes a Rift Between Germany and Egypt". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ "Nefertiti - Ancient History - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ e.V., Verein zur Förderung des Ägyptischen Museums und Papyrussammlung Berlin. "Nefertiti: (Society for the Promotion of the Egyptian Museum Berlin)". www.egyptian-museum-berlin.com. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan. "The Bust of Nefertiti: Remembering Ancient Egypt’s Famous Queen". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan. "The Bust of Nefertiti: Remembering Ancient Egypt’s Famous Queen". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Tharoor, Ishaan. "The Bust of Nefertiti: Remembering Ancient Egypt’s Famous Queen". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ "Nefertiti Bust May Be 100 Years Old, Not 3,000: Martin Gayford". Bloomberg.

- 1 2 3 4 Maryalice Yakutchik. "Who Was Nefertiti?". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Silverman, Wegner, Wegner pp.130-33

- ↑ Athena van der Perre, The Year 16 graffito of Akhenaten in Dayr Abū Ḥinnis. A Contribution to the Study of the Later Years of Nefertiti, Journal of Egyptian History (JEH) 7 (2014), pp.67-108

- ↑ A. Van der Perre, 'Nefertiti's last documented reference for now' F. Seyfried (ed.), In the Light of Amarna. 100 Years of the Nefertiti Discovery, (Berlin, 2012), pp.195-197 (academia.edu)

- 1 2 Christine Dell'Amore (30 March 2009). "Nefertiti's Real, Wrinkled Face Found in Famous Bust?". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ↑ Charlotte Booth (2007-07-30). The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies. for Dummies. ISBN 978-0-470-06544-0.

- 1 2 3 Breger p. 285

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Siehr p.115

- 1 2 3 4 Connolly, Kate (7 May 2009). "Is this Nefertiti – or a 100-year-old fake?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Archaeological Controversy: Did Germany Cheat to Get Bust of Nefertiti?". Spiegel Online. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roger Boyes (20 October 2009). "Neues Museum refuses to return the bust of Queen Nefertiti to Egyptian museum". The Times. London. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ Berger p. 288

- 1 2 3 Breger p. 286

- ↑ "Top 10 Plundered Artifacts". TIME. 5 March 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Nefertiti's 'hidden face' proves Berlin bust is not Hitler's fake". Science News. 27 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2009. For pictures, "Nefertiti's 'Hidden Face' Proves Famous Berlin Bust is not Hitler's Fake". 3 April 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ↑ Horst Woldemar Janson; Anthony F. Janson (2003). History of art: the Western tradition. Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7.

- 1 2 3 Silverman, Wegner, Wegner pp. 21, 113

- 1 2 Schultz. Egypt the World of Pharaohs: The World of the Pharaohs. American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-977-424-661-6.

- 1 2 Helen Gardner (2006). "Art of Ancient Egypt". Gardner's Art Through the Ages: the western perspective. Cengage Learning. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-495-00478-3.

- ↑ Silverman, David P. (1997). Ancient Egypt. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-19-521952-X.

- ↑ Rudolf Anthes (1961). Nofretete – The Head of Queen Nofretete. Mann, Berlin: Verlag Gebr. p. 6.

- ↑ Matthias Schulz (2012). "Die entführte Königin (German)". Der Spiegel. 49 (3.12.2012): 128.

- ↑ Joyce A. Tyldesley, Nefertiti: Egypt's sun queen, Viking, 1999, p.196.

- ↑ Fred Gladstone Bratton, A history of Egyptian archaeology, Hale, 1968, p.223

- 1 2 3 4 Lorenzi, R (5 September 2006). "Scholar: Nefertiti Was an Aging Beauty". Discovery News. Discovery Channel. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- 1 2 Szabo, Christopher (12 May 2009). "Egypt's Rubbishes Claims that Nefertiti Bust is 'Fake'". DigitalJournal.com.

- 1 2 Patrick McGroarty (31 March 2009). "Nefertiti Bust Has Two Faces". Discovery News. Discovery Channel. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- 1 2 For comparative analysis between 1992 and 2006 CT scans: Bernhard Illerhaus; Andreas Staude; Dietmar Meinel (2009). "Nondestructive Insights into Composition of the Sculpture of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti with CT and the dependence of object surface from image processing" (PDF). NDT Database & e-Journal of Nondestructive Testing.

- ↑ Alexander Huppertz, A; Dietrich Wildung; Barry J. Kemp; Tanja Nentwig; Patrick Asbach; Franz Maximilian Rosche; Bernd Hamm (April 2009). "Nondestructive Insights into Composition of the Sculpture of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti with CT". Radiology. Radiological Society of North America. 251 (1): 233–240. PMID 19332855. doi:10.1148/radiol.2511081175.

- ↑ "Hidden Face In Nefertiti Bust Examined With CT Scan". Science Daily. 8 April 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dan Morrison (18 April 2007). "Egypt Vows "Scientific War" If Germany Doesn't Loan Nefertiti". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 Moore, Tristana (7 May 2007). "Row over Nefertiti bust continues". BBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ Siehr p.114

- 1 2 3 Breger p. 292

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "The Bust of Nefertiti: A Chronology". "Nefertiti travels" campaign website. CulturCooperation. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- 1 2 Tony Paterson (17 October 2009). "Queen Nefertiti rules again in Berlin's reborn museum". The Independent. London. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ Isabelle de Pommereau (2 November 2009). "Germany: Time for Egypt's Nefertiti bust to go home?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ "Thutmose's Bust of Nefertiti (Amarna Period)". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sieher p. 116

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael (23 October 2009). "When Ancient Artifacts Become Political Pawns". New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- ↑ Siehr pp. 133–4

- ↑ El-Aref, Nevine (20 July 2005). "Antiquities wish list". Al-Ahram Weekly (751). Archived from the original on 16 September 2010.

- ↑ "Nefertiti travels". CulturCooperation. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ The Associated Press:Egypt antiquities chief to demand Nefertiti bust

- 1 2 HUGH EAKIN (21 June 2003). "Nefertiti's Bust Gets a Body, Offending Egyptians". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ↑ For a picture of "The Body of Nefertiti" see "Nefertiti's Bust Gets a Body, Offending Egyptians: A Problematic Juxtaposition". The New York Times. 21 June 2003. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- 1 2 Breger p. 291

- ↑ Elizabeth Young, "Here Comes the Bride: Wedding Gender and Race in Bride of Frankenstein"; Feminist Studies, Vol. 17, 1991. 35 pgs.

- Books

- Anthes, Rudolph (1961). Nofretete – The Head of Queen Nofretete. Gebr. Mann.

- Breger, Claudia (2006). "The 'Berlin' Nefertiti Bust". In Regina Schulte. The body of the queen: gender and rule in the courtly world, 1500–2000. Berghahn Book. ISBN 1-84545-159-7.

- Siehr, Kurt G (August 2006). "The Beautiful One has come – to Return". In John Henry Merryman. Imperialism, art and restitution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85929-8.

- Silverman, David P.; Wegner, Josef William; Wegner, Jennifer Houser (2006). Akhenaten and Tutankhamun: revolution and restoration. University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology. ISBN 978-1-931707-90-9.

External links

Media related to Nefertiti bust (Berlin) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nefertiti bust (Berlin) at Wikimedia Commons- Neues Museum Berlin