Neferkara I

| Neferkara I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neferka, Aaka, Nephercheres | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

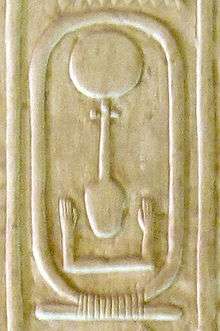

Cartouche name of Neferkara I in the Abydos King List (cartouche no. 19) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | length of reign unknown (2nd Dynasty; around 2740 B.C.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Senedj | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Neferkasokar | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neferkara I (also Neferka and, alternatively, Aaka) is the cartouche name of a king (pharaoh) who is said to have ruled during the 2nd dynasty of Ancient Egypt. The exact length of his reign is unknown since the Turin canon lacks the years of rulership[1] and the ancient Greek historian Manetho suggests that Neferkara´s reign lasted 25 years.[2] Egyptologists evaluate his statement as misinterpretation or exaggeration.

Name sources

The name “Neferkara I” (meaning “the Ka of Re is beautiful”) appears only in the Abydos King list. The royal canon of Turin lists a king´s name which is disputed for its uncertain reading. Egyptologists such as Alan H. Gardiner read “Aaka”,[1] whilst other Egyptologists, such as Jürgen von Beckerath, read “Neferka”. Both kinglists describe Neferkara I as the immediate successor of king Senedj and as the predecessor of king Neferkasokar.[3][4][5]

Identity

There´s no contemporary name source for this king and no Horus name could be connected to Neferkare I up to this day.[3][4] In contrast, Egyptologists such as Kim Ryholt believe that Neferkara/Neferka was identical with a sparsely attested king named Sneferka, which is also thought to be a name worn by king Qaa (last ruler of 1st dynasty) for a short time only. Ryholt thinks that ramesside scribes misleadingly added the symbol of the sun to the name “(S)neferka”, ignoring the fact that the sun itself was no object of divine adoration yet during the 2nd dynasty. For a comparison he points to cartouche names such as Neferkara II from the kinglist of Abydos and Nebkara I. from the Sakkara table.[6]

The ancient Greek historian Manetho called Neferkara I “Népherchêres” and reported, that during this kings rulership “the Nile was flowing with honey for eleven days”. Egyptologists think that this collocation was meant to show up that the realm was flourishing under king Nephercheres.[5][7]

Reign

Egyptologists such as Wolfgang Helck, Nicolas Grimal, Hermann Alexander Schlögl and Francesco Tiradritti believe that king Nynetjer, the third ruler of second dynasty, left a realm that was suffering from an overly complex state administration and that Ninetjer decided to split Egypt to leave it to his two sons (or, at least, rightful throne successors) who would rule two separate kingdoms, in the hope that the two rulers could better administer the states.[8][9] In contrast, Egyptologists such as Barbara Bell believe that an economic catastrophe like a famine or a long lasting drought affected Egypt. Therefore, to address the problem of feeding the Egyptian population, Ninetjer split the realm and his successors founded two independent realms, until the famine came to an end. Bell points to the inscriptions of the Palermo stone, where, in her opinion, the records of the annual Nile floods show constantly low levels during this period.[10] Bell´s theory is refuted today by Egyptologists such as Stephan Seidlmayer, who corrected Bell´s calculations. Seidlmayer has shown that the annual Nile floods were at usual levels at Ninetjer´s time up to the period of the Old Kingdom. Bell had overlooked, that the heights of the Nile floods in the Palermo stone inscription only takes the measurements of the nilometers around Memphis into account, but not elsewhere in Egypt. Any long-lasting drought can therefore be excluded.[11]

It is a commonly accepted theory, that Neferkara I had to share his throne with another ruler. It is just unclear yet, with whom. Later kinglists such as the Sakkara list and the Turin canon list the kings Neferkasokar and Hudjefa I as immediate successors. The Abydos list skips all these three rulers and name a king Djadjay (identical with king Khasekhemwy). If Egypt was already divided when Neferkara I gained the throne, kings like Sekhemib and Peribsen would have ruled Upper Egypt, whilst Neferkara I and his successors would have ruled Lower Egypt. The division of Egypt was brought to an end by king Khasekhemwy.[12]

References

- 1 2 Alan H. Gardiner: The royal canon of Turin. Griffith Institute of Oxford, Oxford (UK) 1997, ISBN 0-900416-48-3; p. 15 & Table I.

- ↑ William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (The Loeb classical Library, Volume 350). Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 2004 (Reprint), ISBN 0-674-99385-3, pp. 37–41.

- 1 2 Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards: The Cambridge ancient history Vol. 1, Pt. 2: Early history of the Middle East, 3rd volume (Reprint). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 0-521-07791-5, p. 35.

- 1 2 Jürgen von Beckerath: Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Deutscher Kunstverlag, München/Berlin 1984, p. 49.

- 1 2 Winfried Barta: Die Chronologie der 1. bis 5. Dynastie nach den Angaben des rekonstruierten Annalensteins. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. (ZAS) volume 108, Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1981, ISSN 0044-216X, pp. 12–14.

- ↑ Kim Ryholt, in: Journal of Egyptian History; vol.1. BRILL, Leiden 2008, ISSN 1874-1657, pp. 159–173.

- ↑ Walter Bryan Emery: Ägypten, Geschichte und Kultur der Frühzeit, 3200-2800 v. Chr. p. 19.

- ↑ Nicolas Grimal: A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell, Weinheim 1994, ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8, p. 55.

- ↑ Francesco Tiradritti & Anna Maria Donadoni Roveri: Kemet: Alle Sorgenti Del Tempo. Electa, Milano 1998, ISBN 88-435-6042-5, p. 80–85.

- ↑ Barbara Bell: Oldest Records of the Nile Floods, In: Geographical Journal, No. 136. 1970, p. 569–573; M. Goedike: Journal of Egypt Archaeology, No. 42. 1998, page 50.

- ↑ Stephan Seidlmayer: Historische und moderne Nilstände: Historische und moderne Nilstände: Untersuchungen zu den Pegelablesungen des Nils von der Frühzeit bis in die Gegenwart. Achet, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-9803730-8-8, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ Hermann Alexander Schlögl: Das Alte Ägypten: Geschichte und Kultur von der Frühzeit bis zu Kleopatra. Beck, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-406-54988-8, pp. 77–78 & 415.

External links

| Preceded by Sekhemib |

Pharaoh of Egypt | Succeeded by Neferkasokar |