Nazi Germany

| German Reich | |||||

| Deutsches Reich[a] | |||||

| |||||

.svg.png) Emblem

| |||||

| Anthem Das Lied der Deutschen Song of the Germans Horst-Wessel-Lied Horst Wessel Song | |||||

| |||||

Administrative divisions of Germany, February 1944 | |||||

| Capital | Berlin | ||||

| Languages | German | ||||

| Government | |||||

| President / Führer | |||||

| • | 1933–1934 | Paul von Hindenburg | |||

| • | 1934–1945 | Adolf Hitler[lower-alpha 2] | |||

| • | 1945 | Karl Dönitz | |||

| Chancellor | |||||

| • | 1933–1945 | Adolf Hitler | |||

| • | 1945 | Joseph Goebbels | |||

| • | 1945 (as leading minister) | Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk | |||

| Legislature | Reichstag | ||||

| • | State council | Reichsrat | |||

| Historical era | Interwar period / World War II | ||||

| • | Machtergreifung | 30 January 1933 | |||

| • | Gleichschaltung | 27 February 1933 | |||

| • | Anschluss | 12 March 1938 | |||

| • | World War II | 1 September 1939 | |||

| • | Death of Adolf Hitler | 30 April 1945 | |||

| • | Surrender of Germany | 8 May 1945 | |||

| • | Final dissolution | 23 May 1945 | |||

| Area | |||||

| • | 1939 [lower-alpha 3] | 633,786 km2 (244,706 sq mi) | |||

| Population | |||||

| • | 1939 (Germany & Austria) est.[lower-alpha 4] | 79,375,281 | |||

| Currency | Reichsmark (ℛℳ) | ||||

| a. | ^ Officially "Großdeutsches Reich" ("Greater German Reich"), 1943–1945. | ||||

Nazi Germany is the common English name for the period in German history from 1933 to 1945, when Germany was governed by a dictatorship under the control of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP). Under Hitler's rule, Germany was transformed into a totalitarian state in which the Nazi Party controlled nearly all aspects of life. The official name of the state was Deutsches Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Großdeutsches Reich ("Greater German Reich") from 1943 to 1945. The period is also known under the names the Third Reich (German: Drittes Reich) and the National Socialist Period (German: Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, abbreviated as NS-Zeit). The Nazi regime came to an end after the Allied Powers defeated Germany in May 1945, ending World War II in Europe.

Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany by the President of the Weimar Republic Paul von Hindenburg on 30 January 1933. The Nazi Party then began to eliminate all political opposition and consolidate its power. Hindenburg died on 2 August 1934, and Hitler became dictator of Germany by merging the powers and offices of the Chancellery and Presidency. A national referendum held 19 August 1934 confirmed Hitler as sole Führer (leader) of Germany. All power was centralised in Hitler's person, and his word became above all laws. The government was not a coordinated, co-operating body, but a collection of factions struggling for power and Hitler's favour. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Nazis restored economic stability and ended mass unemployment using heavy military spending and a mixed economy. Extensive public works were undertaken, including the construction of Autobahnen (motorways). The return to economic stability boosted the regime's popularity.

Racism, especially antisemitism, was a central feature of the regime. The Germanic peoples (the Nordic race) were considered by the Nazis to be the purest branch of the Aryan race, and were therefore viewed as the master race. Millions of Jews and other peoples deemed undesirable by the state were murdered in the Holocaust. Opposition to Hitler's rule was ruthlessly suppressed. Members of the liberal, socialist, and communist opposition were killed, imprisoned, or exiled. Christian churches were also oppressed, with many leaders imprisoned. Education focused on racial biology, population policy, and fitness for military service. Career and educational opportunities for women were curtailed. Recreation and tourism were organised via the Strength Through Joy program, and the 1936 Summer Olympics showcased the Third Reich on the international stage. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels made effective use of film, mass rallies, and Hitler's hypnotic oratory to influence public opinion. The government controlled artistic expression, promoting specific art forms and banning or discouraging others.

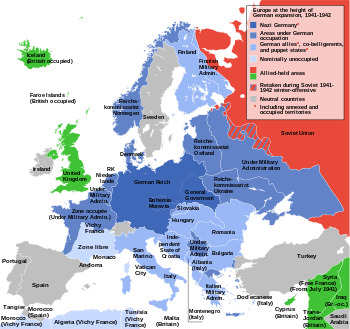

Beginning in the late 1930s, Nazi Germany made increasingly aggressive territorial demands, threatening war if they were not met. It seized Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939. Hitler made a non-aggression pact with Joseph Stalin and invaded Poland in September 1939, launching World War II in Europe. In alliance with Italy and smaller Axis powers, Germany conquered most of Europe by 1940 and threatened Great Britain. Reichskommissariats took control of conquered areas, and a German administration was established in what was left of Poland. Jews and others deemed undesirable were imprisoned, murdered in Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps, or shot.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, the tide gradually turned against the Nazis, who suffered major military defeats in 1943. Large-scale aerial bombing of Germany escalated in 1944, and the Axis powers were pushed back in Eastern and Southern Europe. Following the Allied invasion of France, Germany was conquered by the Soviet Union from the east and the other Allied powers from the west and capitulated within a year. Hitler's refusal to admit defeat led to massive destruction of German infrastructure and additional war-related deaths in the closing months of the war. The victorious Allies initiated a policy of denazification and put many of the surviving Nazi leadership on trial for war crimes at the Nuremberg trials.

Name

The official name of the state was Deutsches Reich from 1933 to 1943, and Großdeutsches Reich from 1943 to 1945.

Common English terms are "Nazi Germany" and "Third Reich". The latter, adopted by Nazi propaganda, was first used in a 1923 book by Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. The book counted the Holy Roman Empire (962–1806) as the first Reich and the German Empire (1871–1918) as the second.[1] The Nazis used it to legitimize their regime as a successor state. After they seized power, Nazi propaganda retroactively referred to the Weimar Republic as the Zwischenreich ("Interim Reich").

Background

The German economy suffered severe setbacks after the end of World War I, partly because of reparations payments required under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The government printed money to make the payments and to repay the country's war debt; the resulting hyperinflation led to inflated prices for consumer goods, economic chaos, and food riots.[2] When the government failed to make the reparations payments in January 1923, French troops occupied German industrial areas along the Ruhr. Widespread civil unrest followed.[3]

The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP;[lower-alpha 5] Nazi Party) was the renamed successor of the German Workers' Party founded in 1919, one of several far-right political parties active in Germany at the time.[4] The party platform included removal of the Weimar Republic, rejection of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, radical antisemitism, and anti-Bolshevism.[5] They promised a strong central government, increased Lebensraum (living space) for Germanic peoples, formation of a national community based on race, and racial cleansing via the active suppression of Jews, who would be stripped of their citizenship and civil rights.[6] The Nazis proposed national and cultural renewal based upon the Völkisch movement.[7]

When the stock market in the United States crashed on 24 October 1929, the effect in Germany was dire. Millions were thrown out of work, and several major banks collapsed. Hitler and the NSDAP prepared to take advantage of the emergency to gain support for their party. They promised to strengthen the economy and provide jobs.[8] Many voters decided the NSDAP was capable of restoring order, quelling civil unrest, and improving Germany's international reputation. After the federal election of 1932, the Nazis were the largest party in the Reichstag, holding 230 seats with 37.4 percent of the popular vote.[9]

History

Nazi seizure of power

Although the Nazis won the greatest share of the popular vote in the two Reichstag general elections of 1932, they did not have a majority, so Hitler led a short-lived coalition government formed by the NSDAP and the German National People's Party.[10] Under pressure from politicians, industrialists, and the business community, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933. This event is known as the Machtergreifung (seizure of power).[11] In the following months, the NSDAP used a process termed Gleichschaltung (co-ordination) to rapidly bring all aspects of life under control of the party.[12] All civilian organisations, including agricultural groups, volunteer organisations, and sports clubs, had their leadership replaced with Nazi sympathisers or party members. By June 1933, virtually the only organisations not in the control of the NSDAP were the army and the churches.[13]

On the night of 27 February 1933, the Reichstag building was set afire; Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutch communist, was found guilty of starting the blaze. Hitler proclaimed that the arson marked the start of a communist uprising. Violent suppression of communists by the Sturmabteilung (SA) was undertaken all over the country, and four thousand members of the Communist Party of Germany were arrested. The Reichstag Fire Decree, imposed on 28 February 1933, rescinded most German civil liberties, including rights of assembly and freedom of the press. The decree also allowed the police to detain people indefinitely without charges or a court order. The legislation was accompanied by a propaganda blitz that led to public support for the measure.[14]

In March 1933, the Enabling Act, an amendment to the Weimar Constitution, passed in the Reichstag by a vote of 444 to 94.[15] This amendment allowed Hitler and his cabinet to pass laws—even laws that violated the constitution—without the consent of the president or the Reichstag.[16] As the bill required a two-thirds majority to pass, the Nazis used the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree to keep several Social Democratic deputies from attending; the Communists had already been banned.[17][18] On 10 May the government seized the assets of the Social Democrats; they were banned in June.[19] The remaining political parties were dissolved, and on 14 July 1933, Germany became a de facto one-party state when the founding of new parties was made illegal.[20] Further elections in November 1933, 1936, and 1938 were entirely Nazi-controlled and saw only the Nazis and a small number of independents elected.[21] The regional state parliaments and the Reichsrat (federal upper house) were abolished in January 1934.[22]

The Nazi regime abolished the symbols of the Weimar Republic, including the black, red, and gold tricolour flag, and adopted reworked imperial symbolism. The previous imperial black, white, and red tricolour was restored as one of Germany's two official flags; the second was the swastika flag of the NSDAP, which became the sole national flag in 1935. The NSDAP anthem "Horst-Wessel-Lied" ("Horst Wessel Song") became a second national anthem.[23]

In this period, Germany was still in a dire economic situation; millions were unemployed and the balance of trade deficit was daunting.[24] Hitler knew that reviving the economy was vital. In 1934, using deficit spending, public works projects were undertaken. A total of 1.7 million Germans were put to work on the projects in 1934 alone.[24] Average wages both per hour and per week began to rise.[25]

The demands of the SA for more political and military power caused anxiety among military, industrial, and political leaders. In response, Hitler purged the entire SA leadership in the Night of the Long Knives, which took place from 30 June to 2 July 1934.[26] Hitler targeted Ernst Röhm and other SA leaders who, along with a number of Hitler's political adversaries (such as Gregor Strasser and former chancellor Kurt von Schleicher), were rounded up, arrested, and shot.[27]

On 2 August 1934, President von Hindenburg died. The previous day, the cabinet had enacted the "Law Concerning the Highest State Office of the Reich", which stated that upon Hindenburg's death, the office of president would be abolished and its powers merged with those of the chancellor.[28] Hitler thus became head of state as well as head of government. He was formally named as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor). Germany was now a totalitarian state with Hitler at its head.[29] As head of state, Hitler became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. The new law altered the traditional loyalty oath of servicemen so that they affirmed loyalty to Hitler personally rather than the office of supreme commander or the state.[30] On 19 August, the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship was approved by 90 percent of the electorate in a plebiscite.[31]

Most Germans were relieved that the conflicts and street fighting of the Weimar era had ended. They were deluged with propaganda orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels, who promised peace and plenty for all in a united, Marxist-free country without the constraints of the Versailles Treaty.[32] The first major Nazi concentration camp, initially for political prisoners, was opened at Dachau in 1933.[33] Hundreds of camps of varying size and function were created by the end of the war.[34] Upon seizing power, the Nazis took repressive measures against their political opposition and rapidly began the comprehensive marginalisation of persons they considered socially undesirable. Under the guise of combating the Communist threat, the National Socialists secured immense power. Above all, their campaign against Jews living in Germany gained momentum.

Beginning in April 1933, scores of measures defining the status of Jews and their rights were instituted at the regional and national level.[35] Initiatives and legal mandates against the Jews reached their culmination with the establishment of the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, stripping them of their basic rights.[36] The Nazis would take from the Jews their wealth, their right to intermarry with non-Jews, and their right to occupy many fields of labour (such as practising law, medicine, or working as educators). They eventually declared them undesirable to remain among German citizens and society, which over time dehumanised the Jews; arguably, these actions desensitised Germans to the extent that it resulted in the Holocaust. Ethnic Germans who refused to ostracise Jews or who showed any signs of resistance to Nazi propaganda were placed under surveillance by the Gestapo, had their rights removed, or were sent to concentration camps.[37] Everyone and everything was monitored in Nazi Germany. Inaugurating and legitimising power for the Nazis was thus accomplished by their initial revolutionary activities, then through the improvisation and manipulation of the legal mechanisms available, through the use of police powers by the Nazi Party (which allowed them to include and exclude from society whomever they chose), and finally by the expansion of authority for all state and federal institutions.[38]

Militaristic foreign policy

As early as February 1933, Hitler announced that rearmament must be undertaken, albeit clandestinely at first, as to do so was in violation of the Versailles Treaty. A year later he told his military leaders that 1942 was the target date for going to war in the east.[39] He pulled Germany out of the League of Nations in 1933, claiming its disarmament clauses were unfair, as they applied only to Germany.[40] The Saarland, which had been placed under League of Nations supervision for 15 years at the end of World War I, voted in January 1935 to become part of Germany.[41] In March 1935 Hitler announced that the Reichswehr would be increased to 550,000 men and that he was creating an air force.[42] Britain agreed that the Germans would be allowed to build a naval fleet with the signing of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement on 18 June 1935.[43]

When the Italian invasion of Ethiopia led to only mild protests by the British and French governments, on 7 March 1936 Hitler used the Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance as a pretext to order the Wehrmacht Heer ground forces to march 3,000 troops into the demilitarised zone in the Rhineland in violation of the Versailles Treaty.[44] As the territory was part of Germany, the British and French governments did not feel that attempting to enforce the treaty was worth the risk of war.[45] In the one-party election held on 29 March, the NSDAP received 98.9 percent support.[45] In 1936 Hitler signed an Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan and a non-aggression agreement with the Fascist Italy of Benito Mussolini, who was soon referring to a "Rome-Berlin Axis".[46]

Hitler sent air and armoured units to assist General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War, which broke out in July 1936. The Soviet Union sent a smaller force to assist the Republican government. Franco's Nationalists were victorious in 1939 and became an informal ally of Nazi Germany.[47]

Austria and Czechoslovakia

In February 1938, Hitler emphasised to Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg the need for Germany to secure its frontiers. Schuschnigg scheduled a plebiscite regarding Austrian independence for 13 March, but Hitler demanded that it be cancelled. On 11 March, Hitler sent an ultimatum to Schuschnigg demanding that he hand over all power to the Austrian NSDAP or face an invasion. The Wehrmacht entered Austria the next day, to be greeted with enthusiasm by the populace.[48]

The Republic of Czechoslovakia was home to a substantial minority of Germans, who lived mostly in the Sudetenland. Under pressure from separatist groups within the Sudeten German Party, the Czechoslovak government offered economic concessions to the region.[49] Hitler decided to incorporate not just the Sudetenland but the whole of Czechoslovakia into the Reich.[50] The Nazis undertook a propaganda campaign to try to drum up support for an invasion.[51] Top leaders of the armed forces were not in favour of the plan, as Germany was not yet ready for war.[52] The crisis led to war preparations by the British, the Czechoslovaks, and France (Czechoslovakia's ally). Attempting to avoid war, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain arranged a series of meetings, the result of which was the Munich Agreement, signed on 29 September 1938. The Czechoslovak government was forced to accept the Sudetenland's annexation into Germany. Chamberlain was greeted with cheers when he landed in London bringing, he said, "peace for our time."[53] The agreement lasted six months before Hitler seized the rest of Czech territory in March 1939.[54] A puppet state was created in Slovakia.[55]

Austrian and Czech foreign exchange reserves were soon seized by the Nazis, as were stockpiles of raw materials such as metals and completed goods such as weaponry and aircraft, which were shipped back to Germany. The Reichswerke Hermann Göring industrial conglomerate took control of steel and coal production facilities in both countries.[56]

Poland

In January 1934 Germany signed a non-aggression pact with Poland, which disrupted the French network of anti-German alliances in Eastern Europe.[57] In March 1939, Hitler demanded the return of the Free City of Danzig and the Polish Corridor, a strip of land that separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany. The British announced they would come to the aid of Poland if it was attacked. Hitler, believing the British would not actually take action, ordered an invasion plan should be readied for a target date of September 1939.[58] On 23 May he described to his generals his overall plan of not only seizing the Polish Corridor but greatly expanding German territory eastward at the expense of Poland. He expected this time they would be met by force.[59]

The Germans reaffirmed their alliance with Italy and signed non-aggression pacts with Denmark, Estonia, and Latvia. Trade links were formalised with Romania, Norway, and Sweden.[60] Hitler's foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, arranged in negotiations with the Soviet Union a non-aggression pact, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which was signed in August 1939.[61] The treaty also contained secret protocols dividing Poland and the Baltic states into German and Soviet spheres of influence.[62][63]

World War II

Foreign policy

Germany's foreign policy during the war involved the creation of allied governments under direct or indirect control from Berlin. A main goal was obtaining soldiers from the senior allies, such as Italy and Hungary, and millions of workers and ample food supplies from subservient allies such as Vichy France.[64] By the fall of 1942, there were 24 divisions from Romania on the Eastern Front, 10 from Italy, and 10 from Hungary.[65] When a country was no longer dependable, Germany assumed full control, as it did with France in 1942, Italy in 1943, and Hungary in 1944. Although Japan was an official powerful ally, the relationship was distant and there was little co-ordination or co-operation. For example, Germany refused to share their formula for synthetic oil from coal until late in the war.[66]

Outbreak of war

Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939. Britain and France declared war on Germany two days later. World War II was under way.[67] Poland fell quickly, as the Soviet Union attacked from the east on 17 September.[68] Reinhard Heydrich, then head of the Gestapo, ordered on 21 September that Jews should be rounded up and concentrated into cities with good rail links. Initially the intention was to deport the Jews to points further east, or possibly to Madagascar.[69] Using lists prepared ahead of time, some 65,000 Polish intelligentsia, noblemen, clergy, and teachers were killed by the end of 1939 in an attempt to destroy Poland's identity as a nation.[70][71] The Soviet forces continued to attack, advancing into Finland in the Winter War, and German forces were involved in action at sea. But little other activity occurred until May, so the period became known as the "Phoney War".[72]

From the start of the war, a British blockade on shipments to Germany affected the Reich economy. The Germans were particularly dependent on foreign supplies of oil, coal, and grain.[73] To safeguard Swedish iron ore shipments to Germany, Hitler ordered an attack on Norway, which took place on 9 April 1940. Much of the country was occupied by German troops by the end of April. Also on 9 April, the Germans invaded and occupied Denmark.[74][75]

Conquest of Europe

Against the judgement of many of his senior military officers, Hitler ordered an attack on France and the Low Countries, which began in May 1940.[76] They quickly conquered Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium, and France surrendered on 22 June.[77] The unexpectedly swift defeat of France resulted in an upswing in Hitler's popularity and a strong upsurge in war fever.[78]

In spite of the provisions of the Hague Convention, industrial firms in the Netherlands, France, and Belgium were put to work producing war materiel for the occupying German military. Officials viewed this option as being preferable to their citizens being deported to the Reich as forced labour.[79]

The Nazis seized from the French thousands of locomotives and rolling stock, stockpiles of weapons, and raw materials such as copper, tin, oil, and nickel.[80] Financial demands were levied on the governments of the occupied countries as well; payments for occupation costs were received from France, Belgium, and Norway.[81] Barriers to trade led to hoarding, black markets, and uncertainty about the future.[82] Food supplies were precarious; production dropped in most areas of Europe, but not as much as during World War I.[83] Greece experienced famine in the first year of occupation and the Netherlands in the last year of the war.[83]

Hitler made peace overtures to the new British leader, Winston Churchill, and upon their rejection he ordered a series of aerial attacks on Royal Air Force airbases and radar stations. However, the German Luftwaffe failed to defeat the Royal Air Force in what became known as the Battle of Britain.[84] By the end of October, Hitler realised the necessary air superiority for his planned invasion of Britain could not be achieved, and he ordered nightly air raids on British cities, including London, Plymouth, and Coventry.[85]

In February 1941, the German Afrika Korps arrived in Libya to aid the Italians in the North African Campaign and attempt to contain Commonwealth forces stationed in Egypt.[86] On 6 April, Germany launched the invasion of Yugoslavia and the battle of Greece.[87] German efforts to secure oil included negotiating a supply from their new ally, Romania, who signed the Tripartite Pact in November 1940.[88][89]

On 22 June 1941, contravening the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, 5.5 million Axis troops attacked the Soviet Union. In addition to Hitler's stated purpose of acquiring Lebensraum, this large-scale offensive (codenamed Operation Barbarossa) was intended to destroy the Soviet Union and seize its natural resources for subsequent aggression against the Western powers.[90] The reaction among Germans was one of surprise and trepidation. Many were concerned about how much longer the war would drag on or suspected that Germany could not win a war fought on two fronts.[91]

The invasion conquered a huge area, including the Baltic republics, Belarus, and West Ukraine. After the successful Battle of Smolensk, Hitler ordered Army Group Centre to halt its advance to Moscow and temporarily divert its Panzer groups to aid in the encirclement of Leningrad and Kiev.[92] This pause provided the Red Army with an opportunity to mobilise fresh reserves. The Moscow offensive, which resumed in October 1941, ended disastrously in December.[92] On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Four days later, Germany declared war on the United States.[93]

Food was in short supply in the conquered areas of the Soviet Union and Poland, with rations inadequate to meet nutritional needs. The retreating armies had burned the crops, and much of the remainder was sent back to the Reich.[94] In Germany itself, food rations had to be cut in 1942. In his role as Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan, Hermann Göring demanded increased shipments of grain from France and fish from Norway. The 1942 harvest was a good one, and food supplies remained adequate in Western Europe.[95]

Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce was an organisation set up to loot artwork and cultural material from Jewish collections, libraries, and museums throughout Europe. Some 26,000 railroad cars full of art treasures, furniture, and other looted items were sent back to Germany from France alone.[96] In addition, soldiers looted or purchased goods such as produce and clothing—items which were becoming harder to obtain in Germany—for shipment back home.[97]

Turning point and collapse

Germany, and Europe as a whole, was almost totally dependent on foreign oil imports.[98] In an attempt to resolve the persistent shortage, Germany launched Fall Blau (Case Blue), an offensive against the Caucasian oilfields, in June 1942.[99] The Red Army launched a counter-offensive on 19 November and encircled the Axis forces, who were trapped in Stalingrad on 23 November.[100] Göring assured Hitler that the 6th Army could be supplied by air, but this turned out to be infeasible.[101] Hitler's refusal to allow a retreat led to the deaths of 200,000 German and Romanian soldiers; of the 91,000 men who surrendered in the city on 31 January 1943, only 6,000 survivors returned to Germany after the war.[102] Soviet forces continued to push the invaders westward after the failed German offensive at the Battle of Kursk, and by the end of 1943, the Germans had lost most of their territorial gains in the east.[103]

In Egypt, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps were defeated by British forces under Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery in October 1942.[104] The Allies landed in Sicily in July 1943, and in Italy in September.[105] Meanwhile, American and British bomber fleets, based in Britain, began operations against Germany. In an effort to destroy German morale, many sorties were intentionally given civilian targets.[106] Soon German aircraft production could not keep pace with losses, and without air cover, the Allied bombing campaign became even more devastating. By targeting oil refineries and factories, they crippled the German war effort by late 1944.[107]

On 6 June 1944, American, British, and Canadian forces established a western front with the D-Day landings in Normandy.[108] On 20 July 1944, Hitler narrowly survived a bomb attack.[109] He ordered savage reprisals, resulting in 7,000 arrests and the execution of more than 4,900 people.[110] The failed Ardennes Offensive (16 December 1944 – 25 January 1945) was the last major German campaign of the war. Soviet forces entered Germany on 27 January.[111] Hitler's refusal to admit defeat and his repeated insistence that the war be fought to the last man led to unnecessary death and destruction in the closing months of the war.[112] Through his Justice Minister, Otto Georg Thierack, he ordered that anyone who was not prepared to fight should be summarily court-martialed. Thousands of people were put to death.[113] In many areas, people looked for ways to surrender to the approaching Allies, in spite of exhortations of local leaders to continue the struggle. Hitler also ordered the intentional destruction of transport, bridges, industries, and other infrastructure—a scorched earth decree—but Armaments Minister Albert Speer was able to keep this order from being fully carried out.[112]

During the Battle of Berlin (16 April 1945 – 2 May 1945), Hitler and his staff lived in the underground Führerbunker, while the Red Army approached.[114] On 30 April, when Soviet troops were one or two blocks away from the Reich Chancellery, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide in the Führerbunker.[115] On 2 May General Helmuth Weidling unconditionally surrendered Berlin to Soviet General Vasily Chuikov.[116] Hitler was succeeded by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz as Reich President and Goebbels as Reich Chancellor.[117] Goebbels and his wife Magda committed suicide the next day, after murdering their six children.[118] On 4–8 May 1945 most of the remaining German armed forces surrendered unconditionally. The German Instrument of Surrender was signed 8 May, marking the end of the Nazi regime and the end of World War II in Europe.[119]

Suicide rates in Germany increased as the war drew to a close, particularly in areas where the Red Army was advancing. More than a thousand people (out of a population of around 16,000) committed suicide in Demmin on and around 1 May 1945 as the 65th Army of 2nd Belorussian Front first broke into a distillery and then rampaged through the town, committing mass rapes, arbitrarily executing civilians, and setting fire to buildings.[120] High numbers of suicides took place in many other locations, including Neubrandenburg (600 dead),[120] Stolp in Pommern (1,000 dead),[120] and Berlin, where at least 7,057 people committed suicide in 1945.[121]

German casualties

Estimates of the total German war dead range from 5.5 to 6.9 million persons.[122] A study by German historian Rüdiger Overmans puts the number of German military dead and missing at 5.3 million, including 900,000 men conscripted from outside of Germany's 1937 borders, in Austria, and in east-central Europe.[123] Overy estimated in 2014 that in all about 353,000 civilians were killed by British and American bombing of German cities.[124] An additional 20,000 died in the land campaign.[125][126] Some 22,000 citizens died during the Battle of Berlin.[127] Other civilian deaths include 300,000 Germans (including Jews) who were victims of Nazi political, racial, and religious persecution,[128] and 200,000 who were murdered in the Nazi euthanasia program.[129] Political courts called Sondergerichte sentenced some 12,000 members of the German resistance to death, and civil courts sentenced an additional 40,000 Germans.[130] Mass rapes of German women also took place.[131]

At the end of the war, Europe had more than 40 million refugees,[132] its economy had collapsed, and 70 percent of its industrial infrastructure was destroyed.[133] Between twelve and fourteen million ethnic Germans fled or were expelled from east-central Europe to Germany.[134] During the Cold War, the West German government estimated a death toll of 2.2 million civilians due to the flight and expulsion of Germans and through forced labour in the Soviet Union.[135] This figure remained unchallenged until the 1990s, when some historians put the death toll at 500,000–600,000 confirmed deaths.[136][137][138] In 2006 the German government reaffirmed its position that 2.0–2.5 million deaths occurred.[lower-alpha 6]

Geography

Territorial changes

As a result of their defeat in World War I and the resulting Treaty of Versailles, Germany lost Alsace-Lorraine, Northern Schleswig, and Memel. The Saarland temporarily became a protectorate of France, under the condition that its residents would later decide by referendum which country to join. Poland became a separate nation and was given access to the sea by the creation of the Polish Corridor, which separated Prussia from the rest of Germany. Danzig was made a free city.[139]

Germany regained control of the Saarland through a referendum held in 1935 and annexed Austria in the Anschluss of 1938.[140] The Munich Agreement of 1938 gave Germany control of the Sudetenland, and they seized the remainder of Czechoslovakia six months later.[53] Under threat of invasion by sea, Lithuania surrendered the Memel district in March 1939.[141]

Between 1939 and 1941, German forces invaded Poland, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the Soviet Union.[77] Trieste, South Tyrol, and Istria were ceded to Germany by Mussolini in 1943.[142] Two puppet districts were set up in the area, the Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral and the Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills.[143]

Occupied territories

Some of the conquered territories were immediately incorporated into Germany as part of Hitler's long-term goal of creating a Greater Germanic Reich. Several areas, such as Alsace-Lorraine, were placed under the authority of an adjacent Gau (regional district). Beyond the territories incorporated into Germany were the Reichskommissariate (Reich Commissariats), quasi-colonial regimes established in a number of occupied countries. Areas placed under German administration included the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Reichskommissariat Ostland (encompassing the Baltic states and Belarus), and Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Conquered areas of Belgium and France were placed under control of the Military Administration in Belgium and Northern France.[145] Belgian Eupen-Malmedy, which had been part of German until 1919, was annexed directly. Part of Poland was immediately incorporated into the Reich, and the General Government was established in occupied central Poland.[146] Hitler intended to eventually incorporate many of these areas into the Reich.[147]

The governments of Denmark, Norway (Reichskommissariat Norwegen), and the Netherlands (Reichskommissariat Niederlande) were placed under civilian administrations staffed largely by natives.[145][lower-alpha 7]

Post-war changes

With the issuance of the Berlin Declaration on 5 June 1945 and later creation of the Allied Control Council, the four Allied powers temporarily assumed governance of Germany.[148] At the Potsdam Conference in August 1945, the Allies arranged for the Allied occupation and denazification of the country. Germany was split into four zones, each occupied by one of the Allied powers, who drew reparations from their zone. Since most of the industrial areas were in the western zones, the Soviet Union was transferred additional reparations.[149] The Allied Control Council disestablished Prussia on 20 May 1947.[150] Aid to Germany began arriving from the United States under the Marshall Plan in 1948.[151] The occupation lasted until 1949, when the countries of East Germany and West Germany were created. Germany finalised her border with Poland by signing the Treaty of Warsaw (1970).[152] Germany remained divided until 1990, when the Allies renounced all claims to German territory with the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, under which Germany also renounced claims to territories lost during World War II.[153]

Politics

Ideology

The NSDAP was a far-right political party which came into its own during the social and financial upheavals that occurred with the onset of the Great Depression in 1929.[154] While in prison after the failed Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, which laid out his plan for transforming German society into one based on race.[155] The ideology of Nazism brought together elements of antisemitism, racial hygiene, and eugenics, and combined them with pan-Germanism and territorial expansionism with the goal of obtaining more Lebensraum for the Germanic people.[156] The regime attempted to obtain this new territory by attacking Poland and the Soviet Union, intending to deport or kill the Jews and Slavs living there, who were viewed as being inferior to the Aryan master race and part of a Jewish Bolshevik conspiracy.[157][158] The Nazi regime believed that only Germany could defeat the forces of Bolshevism and save humanity from world domination by International Jewry.[159] Others deemed life unworthy of life by the Nazis included the mentally and physically disabled, Romani people, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and social misfits.[160][161]

Influenced by the Völkisch movement, the regime was against cultural modernism and supported the development of an extensive military at the expense of intellectualism.[7][162] Creativity and art were stifled, except where they could serve as propaganda media.[163] The party used symbols such as the Blood Flag and rituals such as the Nazi Party rallies to foster unity and bolster the regime's popularity.[164]

Government

Successive Reichsstatthalter decrees between 1933 and 1935 effectively abolished the existing Länder (constituent states) of Germany and replaced them with new administrative divisions, the Gaue, headed by NSDAP leaders (Gauleiters), who effectively became the governor of their respective regions.[165] The change was never fully implemented, as the Länder were still used as administrative divisions for some government departments such as education. This led to a bureaucratic tangle of overlapping jurisdictions and responsibilities typical of the administrative style of the Nazi regime.[166]

Jewish civil servants lost their jobs in 1933, except for those who had seen military service in World War I. Members of the NSDAP or party supporters were appointed in their place.[167] As part of the process of Gleichschaltung, the Reich Local Government Law of 1935 abolished local elections. From that point forward, mayors were appointed by the Ministry of the Interior.[168]

Hitler ruled Germany autocratically by asserting the Führerprinzip (leader principle), which called for absolute obedience of all subordinates. He viewed the government structure as a pyramid, with himself—the infallible leader—at the apex. Rank in the party was not determined by elections; positions were filled through appointment by those of higher rank.[169] The party used propaganda to develop a cult of personality around Hitler.[170] Historians such as Kershaw emphasise the psychological impact of Hitler's skill as an orator.[171] Kressel writes, "Overwhelmingly ... Germans speak with mystification of Hitler's 'hypnotic' appeal".[172] Roger Gill states, "His moving speeches captured the minds and hearts of a vast number of the German people: he virtually hypnotized his audiences."[173]

Top officials reported to Hitler and followed his policies, but they had considerable autonomy.[174] Officials were expected to "work towards the Führer" – to take the initiative in promoting policies and actions in line with his wishes and the goals of the NSDAP, without Hitler having to be involved in the day-to-day running of the country.[175] The government was not a coordinated, co-operating body, but rather a disorganised collection of factions led by members of the party elite who struggled to amass power and gain the Führer's favour.[176] Hitler's leadership style was to give contradictory orders to his subordinates and to place them in positions where their duties and responsibilities overlapped.[177] In this way he fostered distrust, competition, and infighting among his subordinates to consolidate and maximise his own power.[178]

Law

On 20 August 1934, civil servants were required to swear an oath of unconditional obedience to Hitler; a similar oath had been required of members of the military several weeks prior. This law became the basis of the Führerprinzip, the concept that Hitler's word overrode all existing laws.[179] Any acts that were sanctioned by Hitler—even murder—thus became legal.[180] All legislation proposed by cabinet ministers had to be approved by the office of Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, who also had a veto over top civil service appointments.[181]

Most of the judicial system and legal codes of the Weimar Republic remained in use during and after the Nazi era to deal with non-political crimes.[182] The courts issued and carried out far more death sentences than before the Nazis took power.[182] People who were convicted of three or more offences—even petty ones—could be deemed habitual offenders and jailed indefinitely.[183] People such as prostitutes and pickpockets were judged to be inherently criminal and a threat to the racial community. Thousands were arrested and confined indefinitely without trial.[184]

Although the regular courts handled political cases and even issued death sentences for these cases, a new type of court, the Volksgerichtshof (People's Court), was established in 1934 to deal with politically important matters.[185] This court handed out over 5,000 death sentences until its dissolution in 1945.[186] The death penalty could be issued for offences such as being a communist, printing seditious leaflets, or even making jokes about Hitler or other top party officials.[187] Nazi Germany employed three types of capital punishment; hanging, decapitation, and death by shooting.[188] The Gestapo was in charge of investigative policing to enforce National Socialist ideology. They located and confined political offenders, Jews, and others deemed undesirable.[189] Political offenders who were released from prison were often immediately re-arrested by the Gestapo and confined in a concentration camp.[190]

In September 1935 the Nuremberg Laws were enacted. These laws initially prohibited sexual relations and marriages between Aryans and Jews and were later extended to include "Gypsies, Negroes or their bastard offspring".[191] The law also forbade the employment of German women under the age of 45 as domestic servants in Jewish households.[192] The Reich Citizenship Law stated that only those of "German or related blood" were eligible for citizenship.[193] At the same time the Nazis used propaganda to promulgate the concept of Rassenschande (race defilement) to justify the need for a restrictive law.[194] Thus Jews and other non-Aryans were stripped of their German citizenship. The wording of the law also potentially allowed the Nazis to deny citizenship to anyone who was not supportive enough of the regime.[193] A supplementary decree issued in November defined as Jewish anyone with three Jewish grandparents, or two grandparents if the Jewish faith was followed.[195]

Military and paramilitary

Wehrmacht

The unified armed forces of Germany from 1935 to 1945 were called the Wehrmacht. This included the Heer (army), Kriegsmarine (navy), and the Luftwaffe (air force). From 2 August 1934, members of the armed forces were required to pledge an oath of unconditional obedience to Hitler personally. In contrast to the previous oath, which required allegiance to the constitution of the country and its lawful establishments, this new oath required members of the military to obey Hitler even if they were being ordered to do something illegal.[196] Hitler decreed that the army would have to tolerate and even offer logistical support to the Einsatzgruppen—the mobile death squads responsible for millions of deaths in Eastern Europe—when it was tactically possible to do so.[197] Members of the Wehrmacht also participated directly in the Holocaust by shooting civilians or undertaking genocide under the guise of anti-partisan operations.[198] The party line was that the Jews were the instigators of the partisan struggle, and therefore needed to be eliminated.[199] On 8 July 1941, Heydrich announced that all Jews were to be regarded as partisans, and gave the order for all male Jews between the ages of 15 and 45 to be shot.[200]

In spite of efforts to prepare the country militarily, the economy could not sustain a lengthy war of attrition such as had occurred in World War I. A strategy was developed based on the tactic of Blitzkrieg (lightning war), which involved using quick coordinated assaults that avoided enemy strong points. Attacks began with artillery bombardment, followed by bombing and strafing runs. Next the tanks would attack and finally the infantry would move in to secure any ground that had been taken.[201] Victories continued through mid-1940, but the failure to defeat Britain was the first major turning point in the war. The decision to attack the Soviet Union and the decisive defeat at Stalingrad led to the retreat of the German armies and the eventual loss of the war.[202] The total number of soldiers who served in the Wehrmacht from 1935 to 1945 was around 18.2 million, of whom 5.3 million died.[123]

The SA and SS

The Sturmabteilung (SA; Storm Detachment; Brownshirts), founded in 1921, was the first paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. Their initial assignment was to protect Nazi leaders at rallies and assemblies.[203] They also took part in street battles against the forces of rival political parties and violent actions against Jews and others.[204] By 1934, under Ernst Röhm's leadership, the SA had grown to over half a million members—4.5 million including reserves—at a time when the regular army was still limited to 100,000 men by the Versailles Treaty.[205]

Röhm hoped to assume command of the army and absorb it into the ranks of the SA.[206] Hindenburg and Defence Minister Werner von Blomberg threatened to impose martial law if the alarming activities of the SA were not curtailed.[207] Hitler also suspected that Röhm was plotting to depose him, so he ordered the deaths of Röhm and other political enemies. Up to 200 people were killed from 30 June to 2 July 1934 in an event that became known as the Night of the Long Knives.[208] After this purge the SA was no longer a major force.[209]

Initially a force of a dozen men under the auspices of the SA, the Schutzstaffel (SS) grew to become one of the largest and most powerful groups in Nazi Germany.[210] Led by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler from 1929, the SS had over a quarter million members by 1938 and continued to grow.[211] Himmler envisioned the SS as being an elite group of guards, Hitler's last line of defence.[212] The Waffen-SS, the military branch of the SS, became a de facto fourth branch of the Wehrmacht.[213][214]

In 1931 Himmler organised an SS intelligence service which became known as the Sicherheitsdienst (SD; Security Service) under his deputy, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich.[215] This organisation was tasked with locating and arresting communists and other political opponents. Himmler hoped it would eventually totally replace the existing police system.[216][217] Himmler also established the beginnings of a parallel economy under the auspices of the SS Economy and Administration Head Office. This holding company owned housing corporations, factories, and publishing houses.[218][219]

From 1935 forward the SS was heavily involved in the persecution of Jews, who were rounded up into ghettos and concentration camps.[220] With the outbreak of World War II, SS units called Einsatzgruppen followed the army into Poland and the Soviet Union, where from 1941 to 1945 they killed more than two million people, including 1.3 million Jews.[221][222] The SS-Totenkopfverbände (death's head units) were in charge of the concentration camps and extermination camps, where millions more were killed.[223][224]

Economy

Reich economics

The most pressing economic matter the Nazis initially faced was the 30 percent national unemployment rate.[225] Economist Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, President of the Reichsbank and Minister of Economics, created in May 1933 a scheme for deficit financing. Capital projects were paid for with the issuance of promissory notes called Mefo bills. When the notes were presented for payment, the Reichsbank printed money to do so. While the national debt soared, Hitler and his economic team expected that the upcoming territorial expansion would provide the means of repaying the debt.[226] Schacht's administration achieved a rapid decline in the unemployment rate, the largest of any country during the Great Depression.[225]

On 17 October 1933, aviation pioneer Hugo Junkers, owner of the Junkers Aircraft Works, was arrested. Within a few days his company was expropriated by the regime. In concert with other aircraft manufacturers and under the direction of Aviation Minister Göring, production was immediately ramped up industry-wide. From a workforce of 3,200 people producing 100 units per year in 1932, the industry grew to employ a quarter of a million workers manufacturing over 10,000 technically advanced aircraft per year less than ten years later.[227]

An elaborate bureaucracy was created to regulate German imports of raw materials and finished goods with the intention of eliminating foreign competition in the German marketplace and improving the nation's balance of payments. The Nazis encouraged the development of synthetic replacements for materials such as oil and textiles.[228] As the market was experiencing a glut and prices for petroleum were low, in 1933 the Nazi government made a profit-sharing agreement with IG Farben, guaranteeing them a 5 percent return on capital invested in their synthetic oil plant at Leuna. Any profits in excess of that amount would be turned over to the Reich. By 1936, Farben regretted making the deal, as the excess profits by then being generated had to be given to the government.[229]

Major public works projects financed with deficit spending included the construction of a network of Autobahns and providing funding for programmes initiated by the previous government for housing and agricultural improvements.[230] To stimulate the construction industry, credit was offered to private businesses and subsidies were made available for home purchases and repairs.[231] On the condition that the wife would leave the workforce, a loan of up to 1,000 Reichsmarks could be accessed by young couples of Aryan descent who intended to marry. The amount that had to be repaid was reduced by 25 percent for each child born.[232] The caveat that the woman had to remain unemployed was dropped by 1937 due to a shortage of skilled labourers.[233]

Hitler envisioned widespread car ownership as part of the new Germany. He arranged for designer Ferdinand Porsche to draw up plans for the KdF-wagen (Strength Through Joy car), intended to be an automobile that every German citizen could afford. A prototype was displayed at the International Motor Show in Berlin on 17 February 1939. With the outbreak of World War II, the factory was converted to produce military vehicles. No production models were sold until after the war, when the vehicle was renamed the Volkswagen (people's car).[234]

Six million people were unemployed when the Nazis took power in 1933, and by 1937 there were fewer than a million.[235] This was in part due to the removal of women from the workforce.[236] Real wages dropped by 25 percent between 1933 and 1938.[225] Trade unions were abolished in May 1933 with the seizure of the funds and arrest of the leadership of the Social Democratic trade unions. A new organisation, the German Labour Front, was created and placed under NSDAP functionary Robert Ley.[237] The average German worked 43 hours a week in 1933, and by 1939 this increased to 47 hours a week.[238]

By early 1934 the focus shifted away from funding work creation schemes and toward rearmament. By 1935, military expenditures accounted for 73 percent of the government's purchases of goods and services.[239] On 18 October 1936 Hitler named Göring as Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan, intended to speed up the rearmament programme.[240] In addition to calling for the rapid construction of steel mills, synthetic rubber plants, and other factories, Göring instituted wage and price controls and restricted the issuance of stock dividends.[225] Large expenditures were made on rearmament, in spite of growing deficits.[241] With the introduction of compulsory military service in 1935, the Reichswehr, which had been limited to 100,000 by the terms of the Versailles Treaty, expanded to 750,000 on active service at the start of World War II, with a million more in the reserve.[242] By January 1939, unemployment was down to 301,800, and it dropped to only 77,500 by September.[243]

Wartime economy and forced labour

The Nazi war economy was a mixed economy that combined a free market with central planning; historian Richard Overy described it as being somewhere in between the command economy of the Soviet Union and the capitalist system of the United States.[244]

In 1942, after the death of Armaments Minister Fritz Todt, Hitler appointed Albert Speer as his replacement.[245] Speer improved production via streamlined organisation, the use of single-purpose machines operated by unskilled workers, rationalisation of production methods, and better co-ordination between the many different firms that made tens of thousands of components. Factories were relocated away from rail yards, which were bombing targets.[246][247] By 1944, the war was consuming 75 percent of Germany's gross domestic product, compared to 60 percent in the Soviet Union and 55 percent in Britain.[248]

The wartime economy relied heavily upon the large-scale employment of forced labourers. Germany imported and enslaved some 12 million people from 20 European countries to work in factories and on farms; approximately 75 percent were Eastern European.[249] Many were casualties of Allied bombing, as they received poor air raid protection. Poor living conditions led to high rates of sickness, injury, and death, as well as sabotage and criminal activity.[250] The wartime economy also relied upon large-scale robbery, initially through the state seizing the property of Jewish citizens, and later by also plundering the resources of occupied territories.[251]

Foreign workers brought into Germany were put into four different classifications; guest workers, military internees, civilian workers, and Eastern workers. Different regulations were placed upon the worker depending on their classification. To separate Germans and foreign workers, the Nazis issued a ban on sexual relations between Germans and foreign workers.[252][253]

Women played an increasingly large role. By 1944 over a half million served as auxiliaries in the German armed forces, especially in anti-aircraft units of the Luftwaffe; a half million worked in civil aerial defence; and 400,000 were volunteer nurses. They also replaced men in the wartime economy, especially on farms and in small family-owned shops.[254]

Very heavy strategic bombing by the Allies targeted refineries producing synthetic oil and gasoline as well as the German transportation system, especially rail yards and canals.[255] The armaments industry began to break down by September 1944. By November fuel coal was no longer reaching its destinations, and the production of new armaments was no longer possible.[256] Overy argues that the bombing strained the German war economy and forced it to divert up to one-fourth of its manpower and industry into anti-aircraft resources, which very likely shortened the war.[257]

Racial policy

Racism and antisemitism were basic tenets of the NSDAP and the Nazi regime. Nazi Germany's racial policy was based on their belief in the existence of a superior master race. The Nazis postulated the existence of a racial conflict between the Aryan master race and inferior races, particularly Jews, who were viewed as a mixed race that had infiltrated society and were responsible for the exploitation and repression of the Aryan race.[258]

Persecution of Jews

Discrimination against Jews began immediately after the seizure of power; following a month-long series of attacks by members of the SA on Jewish businesses, synagogues, and members of the legal profession, on 1 April 1933 Hitler declared a national boycott of Jewish businesses.[259] The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, passed on 7 April, forced all non-Aryan civil servants to retire from the legal profession and civil service.[260] Similar legislation soon deprived Jewish members of other professions of their right to practise. On 11 April a decree was promulgated that stated anyone who had even one Jewish parent or grandparent was considered non-Aryan. As part of the drive to remove Jewish influence from cultural life, members of the National Socialist Student League removed from libraries any books considered un-German, and a nationwide book burning was held on 10 May.[261]

Violence and economic pressure were used by the regime to encourage Jews to voluntarily leave the country.[262] Jewish businesses were denied access to markets, forbidden to advertise in newspapers, and deprived of access to government contracts. Citizens were harassed and subjected to violent attacks.[263] Many towns posted signs forbidding entry to Jews.[264]

In November 1938, a young Jewish man requested an interview with the German ambassador in Paris. He met with a legation secretary, whom he shot and killed to protest his family's treatment in Germany. This incident provided the pretext for a pogrom the NSDAP incited against the Jews on 9 November 1938. Members of the SA damaged or destroyed synagogues and Jewish property throughout Germany. At least 91 German Jews were killed during this pogrom, later called Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass.[265][266] Further restrictions were imposed on Jews in the coming months – they were forbidden to own businesses or work in retail shops, drive cars, go to the cinema, visit the library, or own weapons. Jewish pupils were removed from schools. The Jewish community was fined one billion marks to pay for the damage caused by Kristallnacht and told that any money received via insurance claims would be confiscated.[267] By 1939 around 250,000 of Germany's 437,000 Jews emigrated to the United States, Argentina, Great Britain, Palestine, and other countries.[268][269] Many chose to stay in continental Europe. Emigrants to Palestine were allowed to transfer property there under the terms of the Haavara Agreement, but those moving to other countries had to leave virtually all their property behind, and it was seized by the government.[269]

Persecution of Roma

Like the Jews, the Romani people were subjected to persecution from the early days of the regime. As a non-Aryan race, they were forbidden to marry people of German extraction. Romani were shipped to concentration camps starting in 1935 and were killed in large numbers.[160][161]

People with disabilities

Action T4 was a programme of systematic murder of the physically and mentally handicapped and patients in psychiatric hospitals that mainly took place from 1939 to 1941 and continued until the end of the war. Initially the victims were shot by the Einsatzgruppen and others; in addition gas chambers and gas vans using carbon monoxide were used by early 1940.[270][271] Under the provisions of a law promulgated 14 July 1933, the Nazi regime carried out the compulsory sterilisation of over 400,000 individuals labelled as having hereditary defects.[272] More than half the people sterilised were those considered mentally deficient, which included not only people who scored poorly on intelligence tests, but those who deviated from expected standards of behaviour regarding thrift, sexual behaviour, and cleanliness. Mentally and physically ill people were also targeted. The majority of the victims came from disadvantaged groups such as prostitutes, the poor, the homeless, and criminals.[273] Other groups persecuted and killed included Jehovah's Witnesses, homosexuals, social misfits, and members of the political and religious opposition.[161][274]

The Holocaust

Germany's war in the East was based on Hitler's long-standing view that Jews were the great enemy of the German people and that Lebensraum was needed for Germany's expansion. Hitler focused his attention on Eastern Europe, aiming to defeat Poland, the Soviet Union and remove or kill the resident Jews and Slavs in the process.[157][158] After the occupation of Poland, all Jews living in the General Government were confined to ghettos, and those who were physically fit were required to perform compulsory labour.[275] In 1941 Hitler decided to destroy the Polish nation completely. He planned that within 10 to 20 years the section of Poland under German occupation would be cleared of ethnic Poles and resettled by German colonists.[276] About 3.8 to 4 million Poles would remain as slaves,[277] part of a slave labour force of 14 million the Nazis intended to create using citizens of conquered nations in the East.[158][278]

The Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) called for deporting the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Siberia, for use as slave labour or to be murdered.[279] To determine who should be killed, Himmler created the Volksliste, a system of classification of people deemed to be of German blood.[280] He ordered that those of Germanic descent who refused to be classified as ethnic Germans should be deported to concentration camps, have their children taken away, or be assigned to forced labour.[281][282] The plan also included the kidnapping of children deemed to have Aryan-Nordic traits, who were presumed to be of German descent.[283] The goal was to implement Generalplan Ost after the conquest of the Soviet Union, but when the invasion failed, Hitler had to consider other options.[279][284] One suggestion was a mass forced deportation of Jews to Poland, Palestine, or Madagascar.[275]

Somewhere around the time of the failed offensive against Moscow in December 1941, Hitler resolved that the Jews of Europe were to be exterminated immediately.[285] Plans for the total eradication of the Jewish population of Europe—eleven million people—were formalised at the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942. Some would be worked to death and the rest would be killed in the implementation of Die Endlösung der Judenfrage (the Final Solution of the Jewish question).[286] Initially the victims were killed with gas vans or by Einsatzgruppen firing squads, but these methods proved impracticable for an operation of this scale.[287] By 1941, killing centres at Auschwitz concentration camp, Sobibor, Treblinka, and other Nazi extermination camps replaced Einsatzgruppen as the primary method of mass killing.[288] The total number of Jews murdered during the war is estimated at 5.5 to six million people,[224] including over a million children.[289] Twelve million people were put into forced labour.[249]

German citizens (despite much of the later denial) had access to information about what was happening, as soldiers returning from the occupied territories would report on what they had seen and done.[290] Evans states that most German citizens disapproved of the genocide.[291][lower-alpha 8] Some Polish citizens tried to rescue or hide the remaining Jews, and members of the Polish underground got word to their government in exile in London as to what was happening.[292]

In addition to eliminating Jews, the Nazis also planned to reduce the population of the conquered territories by 30 million people through starvation in an action called the Hunger Plan. Food supplies would be diverted to the German army and German civilians. Cities would be razed and the land allowed to return to forest or resettled by German colonists.[293] Together, the Hunger Plan and Generalplan Ost would have led to the starvation of 80 million people in the Soviet Union.[294] These partially fulfilled plans resulted in the democidal deaths of an estimated 19.3 million civilians and prisoners of war.[295]

Oppression of ethnic Poles

Poles were viewed by Nazis as subhuman non-Aryans. During the German occupation of Poland, 2.7 million ethnic Poles were killed by the Nazis.[296] Polish civilians were subject to forced labour in German industry, internment, wholesale expulsions to make way for German colonists and mass executions. The German authorities engaged in a systematic effort to destroy Polish culture and national identity. During operation AB-Aktion, many university professors and members of the Polish intelligentsia were arrested and executed, or transported to concentration camps. During the war, Poland lost an estimated 39 to 45 percent of its physicians and dentists, 26 to 57 percent of its lawyers, 15 to 30 percent of its teachers, 30 to 40 percent of its scientists and university professors, and 18 to 28 percent of its clergy.[297]

Mistreatment of Soviet POWs

During the war between June 1941 and January 1942, the Nazis killed an estimated 2.8 million Soviet prisoners of war.[298] Many starved to death while being held in open-air pens at Auschwitz and elsewhere.[299] The Soviet Union lost 27 million people during the war; less than nine million of these were combat deaths.[300] One in four of the population were killed or wounded.[301]

Society

Education

Antisemitic legislation passed in 1933 led to the removal all of Jewish teachers, professors, and officials from the education system. Most teachers were required to belong to the Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund (National Socialist Teachers League; NSLB), and university professors were required to join the National Socialist German Lecturers.[303][304] Teachers had to take an oath of loyalty and obedience to Hitler, and those who failed to show sufficient conformity to party ideals were often reported by students or fellow teachers and dismissed.[305][306] Lack of funding for salaries led to many teachers leaving the profession. The average class size increased from 37 in 1927 to 43 in 1938 due to the resulting teacher shortage.[307]

Frequent and often contradictory directives were issued by Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick, Bernhard Rust of the Reichserziehungsministerium (Ministry of Education), and various other agencies regarding content of lessons and acceptable textbooks for use in primary and secondary schools.[308] Books deemed unacceptable to the regime were removed from school libraries.[309] Indoctrination in National Socialist thought was made compulsory in January 1934.[309] Students selected as future members of the party elite were indoctrinated from the age of 12 at Adolf Hitler Schools for primary education and National Political Institutes of Education for secondary education. Detailed National Socialist indoctrination of future holders of elite military rank was undertaken at Order Castles.[310]

Primary and secondary education focused on racial biology, population policy, culture, geography, and especially physical fitness.[311] The curriculum in most subjects, including biology, geography, and even arithmetic, was altered to change the focus to race.[312] Military education became the central component of physical education, and education in physics was oriented toward subjects with military applications, such as ballistics and aerodynamics.[313][314] Students were required to watch all films prepared by the school division of the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.[309]

At universities, appointments to top posts were the subject of power struggles between the education ministry, the university boards, and the National Socialist German Students' League.[315] In spite of pressure from the League and various government ministries, most university professors did not make changes to their lectures or syllabus during the Nazi period.[316] This was especially true of universities located in predominately Catholic regions.[317] Enrolment at German universities declined from 104,000 students in 1931 to 41,000 in 1939. But enrolment in medical schools rose sharply; Jewish doctors had been forced to leave the profession, so medical graduates had good job prospects.[318] From 1934, university students were required to attend frequent and time-consuming military training sessions run by the SA.[319] First-year students also had to serve six months in a labour camp for the Reichsarbeitsdienst (National Labour Service); an additional ten weeks service were required of second-year students.[320]

Oppression of churches

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, 67 percent of the population of Germany was Protestant, 33 percent was Roman Catholic, while Jews made up less than 1 percent.[321][322] According to 1939 census, 54 percent considered themselves Protestant, 40 percent Roman Catholic, 3.5 percent Gottgläubig (God-believing; a Nazi religious movement), and 1.5 percent nonreligious.[323]

Under the Gleichschaltung process, Hitler attempted to create a unified Protestant Reich Church from Germany's 28 existing Protestant state churches,[324] with the ultimate goal of eradication of the churches in Germany.[325] Ludwig Müller, a pro-Nazi, was installed as Reich Bishop, and the German Christians, a pro-Nazi pressure group, gained control of the new church.[326] They objected to the Old Testament because of its Jewish origins, and demanded that converted Jews be barred from their church.[327] Pastor Martin Niemöller responded with the formation of the Confessing Church, from which some clergymen opposed the Nazi regime.[328] When in 1935 the Confessing Church synod protested the Nazi policy on religion, 700 of their pastors were arrested.[329] Müller resigned and Hitler appointed Hanns Kerrl as Minister for Church Affairs, to continue efforts to control Protestantism.[330] In 1936, a Confessing Church envoy protested to Hitler against the religious persecutions and human rights abuses.[329] Hundreds more pastors were arrested.[330] The church continued to resist, and by early 1937 Hitler abandoned his hope of uniting the Protestant churches.[329] The Confessing Church was banned on 1 July 1937. Niemöller was arrested and confined, first in Sachsenhausen concentration camp and then at Dachau.[331] Theological universities were closed and more pastors and theologians were arrested.[329]

Persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the Nazi takeover.[333] Hitler moved quickly to eliminate political Catholicism, rounding up functionaries of the Catholic-aligned Bavarian People's Party and Catholic Centre Party, which, along with all other non-Nazi political parties, ceased to exist by July.[334] The Reichskonkordat (Reich Concordat) treaty with the Vatican was signed in 1933, amid continuing harassment of the church in Germany.[272] The treaty required the regime to honour the independence of Catholic institutions and prohibited clergy from involvement in politics.[335] Hitler routinely disregarded the Concordat, closing all Catholic institutions whose functions were not strictly religious.[336] Clergy, nuns, and lay leaders were targeted, with thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped-up charges of currency smuggling or immorality.[337] Several high-profile Catholic lay leaders were targeted in the 1934 Night of the Long Knives assassinations.[338][339][340] Most Catholic youth groups refused to dissolve themselves and Hitler Youth leader Baldur von Schirach encouraged members to attack Catholic boys in the streets.[341] Propaganda campaigns claimed the church was corrupt, restrictions were placed on public meetings, and Catholic publications faced censorship. Catholic schools were required to reduce religious instruction and crucifixes were removed from state buildings.[342]

Pope Pius XI had the "Mit brennender Sorge" ("With Burning Concern") Encyclical smuggled into Germany for Passion Sunday 1937 and read from every pulpit. It denounced the systematic hostility of the regime toward the church.[337][343] In response, Goebbels renewed the regime's crackdown and propaganda against Catholics. Enrolment in denominational schools dropped sharply, and by 1939 all such schools were disbanded or converted to public facilities.[344] Later Catholic protests included the 22 March 1942 pastoral letter by the German bishops on "The Struggle against Christianity and the Church".[345] About 30 percent of Catholic priests were disciplined by police during the Nazi era.[346][347] A vast security network spied on the activities of clergy, and priests were frequently denounced, arrested, or sent to concentration camps – many to the dedicated clergy barracks at Dachau.[348] In the areas of Poland annexed in 1939, the Nazis instigated a brutal suppression and systematic dismantling of the Catholic Church.[349][350]

Health

Nazi Germany had a strong anti-tobacco movement. Pioneering research by Franz H. Müller in 1939 demonstrated a causal link between tobacco smoking and lung cancer.[351] The Reich Health Office took measures to try to limit smoking, including producing lectures and pamphlets.[352] Smoking was banned in many workplaces, on trains, and among on-duty members of the military.[353] Government agencies also worked to control other carcinogenic substances such as asbestos and pesticides.[354] As part of a general public health campaign, water supplies were cleaned up, lead and mercury were removed from consumer products, and women were urged to undergo regular screenings for breast cancer.[355]

Government-run health care insurance plans were available, but Jews were denied coverage starting in 1933. That same year, Jewish doctors were forbidden to treat government-insured patients. In 1937 Jewish doctors were forbidden to treat non-Jewish patients, and in 1938 their right to practice medicine was removed entirely.[356]

Medical experiments, many of them pseudoscientific, were performed on concentration camp inmates beginning in 1941.[357] The most notorious doctor to perform medical experiments was SS-Hauptsturmführer Dr Josef Mengele, camp doctor at Auschwitz.[358] Many of his victims died or were intentionally killed.[359] Concentration camp inmates were made available for purchase by pharmaceutical companies for drug testing and other experiments.[360]

Role of women and family

Women were a cornerstone of Nazi social policy. The Nazis opposed the feminist movement, claiming that it was the creation of Jewish intellectuals, and instead advocated a patriarchal society in which the German woman would recognise that her "world is her husband, her family, her children, and her home."[236] Soon after the seizure of power, feminist groups were shut down or incorporated into the National Socialist Women's League. This organisation coordinated groups throughout the country to promote motherhood and household activities. Courses were offered on childrearing, sewing, and cooking.[361] The League published the NS-Frauen-Warte, the only NSDAP-approved women's magazine in Nazi Germany.[362] Despite some propaganda aspects, it was predominantly an ordinary woman's magazine.[363]

Women were encouraged to leave the workforce, and the creation of large families by racially suitable women was promoted through a propaganda campaign. Women received a bronze award—known as the Ehrenkreuz der Deutschen Mutter (Cross of Honour of the German Mother)—for giving birth to four children, silver for six, and gold for eight or more.[361] Large families received subsidies to help with their utilities, school fees, and household expenses. Though the measures led to increases in the birth rate, the number of families having four or more children declined by five percent between 1935 and 1940.[364] Removing women from the workforce did not have the intended effect of freeing up jobs for men. Women were for the most part employed as domestic servants, weavers, or in the food and drink industries—jobs that were not of interest to men.[365] Nazi philosophy prevented large numbers of women from being hired to work in munitions factories in the build-up to the war, so foreign labourers were brought in. After the war started, slave labourers were extensively used.[366] In January 1943 Hitler signed a decree requiring all women under the age of fifty to report for work assignments to help the war effort.[367] Thereafter, women were funnelled into agricultural and industrial jobs. By September 1944, 14.9 million women were working in munitions production.[368]

The Nazi regime discouraged women from seeking higher education. Nazi leaders held conservative views about women and endorsed the idea that rational and theoretical work was alien to a woman's nature since they were considered inherently emotional and instinctive – as such, engaging in academics and careerism would only "divert them from motherhood."[369] The number of women allowed to enroll in universities dropped drastically, as a law passed in April 1933 limited the number of females admitted to university to ten percent of the number of male attendees.[370] Female enrolment in secondary schools dropped from 437,000 in 1926 to 205,000 in 1937. The number of women enrolled in post-secondary schools dropped from 128,000 in 1933 to 51,000 in 1938. However, with the requirement that men be enlisted into the armed forces during the war, women comprised half of the enrolment in the post-secondary system by 1944.[371]